Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Prologue: AMERICA: 1925 | 1 | (12) | |

| One: WHERE DEATH WAITS | 13 | (31) | |

| Two: AIN'T NO SLAVERY NO MORE | 44 | (26) | |

| Three: MIGRATION | 70 | (32) | |

| Four: UPLIFT ME, PRIDE | 102 | (31) | |

| Five: WHITE HOUSES | 133 | (37) | |

| Six: THE LETTER OF YOUR LAW | 170 | (27) | |

| Seven: FREEDMEN, SONS OF GOD, AMERICANS | 197 | (32) | |

| Eight: THE PRODIGAL SON | 229 | (31) | |

| Nine: PREJUDICE | 260 | (40) | |

| Ten: JUDGMENT DAY | 300 | (37) | |

| Epilogue: REQUIESCAM | 337 | (10) | |

| NOTES | 347 | (50) | |

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | 397 | (6) | |

| INDEX | 403 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

ONE

WHERE DEATH WAITS

The streets of Detroit shimmered with heat. Most years, autumn arrived the first week of September. Not in 1925. Two days past Labor Day and the sun blazed like July. Heat curled up from the asphalt, wrapped around telephone poles and streetlight stanchions, drifted past the unmarked doors of darkened speakeasies, seeped through windows thrown open to catch a breeze, and settled into the city’s flats and houses where it lay, thick and oppressive, as afternoon edged into evening.1

Detroit had been an attractive place in the nineteenth century, a medium-size midwestern city made graceful by its founders’ French design. Five broad boulevards radiated outward like the spokes of a wheel—one each running east, northeast, north, northwest, and west—from the compact downtown. Detroit’s grand promenades, these boulevards were lined with the mansions of the well-to-do, mammoth stone churches, imposing businesses, and exclusive clubs. Between the boulevards lay Detroit’s neighborhoods, row after row of modest single-family homes interspersed with empty lots, waiting for the development that boosters continually claimed was coming but never seemed to arrive.2

The auto boom changed everything. Plenty of cities had automakers in the early days, but Detroit had the young industry’s geniuses, practical men seduced by the beauty of well-ordered mechanical systems and fascinated by the challenge of efficiency. German and French manufacturers had invented automobiles in the 1870s. It was Detroit’s brilliance to reinvent them. In the early days of the twentieth century, the city’s aspiring automakers had disassembled the European-made horseless carriages, studying every part, tinkering with the designs, searching for ways to make them work more smoothly and to manufacture them more cheaply. By 1914, when Henry Ford unveiled his restructured Highland Park plant north of downtown, the process was complete. Ford had created a factory as complex as the automobile itself, floor after floor full of machines intricately designed and artfully arranged to make and assemble auto parts faster than anyone thought possible. Three hundred thousand Model T’s rolled out of the factory that year, inexpensive, elegantly simple, utterly dependable cars for ordinary folk like Ford himself.3

Ford’s triumph triggered the industrial version of a gold rush. Other manufacturers grabbed great parcels of land for factories. The Dodge Brothers, John and Horace, started work on a complex large enough to rival Ford’s on the northeast side; Walter Chrysler built a sprawling plant on the far reaches of the east side, near the Detroit River; Walter O. Briggs scattered a series of factories across the city. Aspiring entrepreneurs filled the side streets with tiny machine shops and parts plants that they hoped would earn them a cut of seemingly unending profits. The frenzy transformed Detroit itself into a great machine. By 1925, its grand boulevards were shadowed by stark factory walls and canopied by tangles of telephone lines and streetcar cables. Once fine buildings were now enveloped in a perpetual haze from dozens of coal-fired furnaces.4

More than a decade had passed since Henry Ford, desperate to keep his workers on the line, doubled their wages to an unprecedented five dollars a day. Word of Detroit’s high-paying jobs had shot through Pennsylvania mining camps, British shipyards, Mississippi farmhouses, and peasant villages from Sonora to Abruzzi. Tens of thousands of working people poured into the city, lining up at the factory gates, looking for their share of the machinists’ dream. Eleven years on, they were still coming. In 1900, when Ford was first organizing his company, Detroit had 285,000 people living within its city limits. By 1925, it had 1.25 million. Only New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia were bigger, and Detroit was rapidly closing the gap. “Detroit is Eldorado,” wrote an awed magazine reporter. “It is staccato American. It is shockingly dynamic.”5

And it was completely overwhelming. While the auto magnates retreated to the serenity of their sparkling new suburban estates, working people struggled to hold on to a sliver of space somewhere in Detroit’s vast grid of smoke gray side streets. In the center city, where Negroes and the poorest immigrants lived, two, three, or more families shared tiny workmen’s cottages built generations before. Single men jammed into desperately overcrowded rooming houses, sleeping in shifts so that landlords could double the fees they collected for the privilege of eight hours’ rest on flea-infested mattresses. Beyond the inner ring, a mile or so from downtown, the nineteenth-century city gradually gave way to a sprawl of new neighborhoods. First came vast tracts of flats and jerry-rigged houses for those members of the working class lucky enough to find five-dollar-a-day jobs. Immigrants clustered on the east side of the city, the native-born on the west side, all of them paying premium prices for homes slapped up amid factories, warehouses, and railroad yards or along barren streetscapes. Workers’ neighborhoods blended almost imperceptibly into areas dominated by craftsmen and clerks, Detroit’s solid middle strata, who struggled mightily to afford the tiny touches that set them apart from the masses: a bit of distance from the factory gates, a patch of grass front and back. Finally, out near the suburbs’ borders lay pockets of comfortable middle-class houses, miniature versions of the mock Tudors and colonial revivals favored by the upper crust, so beyond the means of most Detroiters it wasn’t even worth the effort of dreaming about them.6

Garland Avenue sat squarely in the middle range, four miles east of downtown, halfway between the squalor of the inner city and the splendor of suburban Grosse Pointe. Despite its name, it wasn’t an avenue at all. It was just a side street, two miles of pavement running straight north from Jefferson Avenue, Detroit’s southeastern boulevard, to Gratiot Avenue, the northeastern boulevard.

In 1900, Garland was nothing more than a plan on a plat book, but developers had raced to fill it in. To squeeze out every bit of space, they cut the street into long blocks, broken by cross streets that could serve as business strips. Then they sliced each block into twenty or thirty thin lots 35 feet wide and 125 feet deep. A few plots were sold to families who wanted to build their own homes, the way working people always used to do. On the remaining lots, developers built utilitarian houses for the middling sort: long, narrow wood-frame, two-family flats, one apartment up, another down, each with its own entrance off a porch that ran the length of the front. Behind each house was a small yard, barely big enough for a garden, leading out to the alleyway; in front was a postage-stamp lawn running from the porch to the spindly elms planted at curb-side. Only a few feet of open space separated one building from another, a space so small that, from the right angle, the houses seemed to fade one into another, much as one machine seemed to fade into another along an assembly line.7

The people who lived up and down the street didn’t have the education, the credentials, or the polish of the lawyers, accountants, and college professors who lived in the city’s outer reaches. But they had all the attributes necessary to keep themselves out of the inner city, and that’s what mattered most. Of course, they were white, each and every one. The vast majority of them were American born, and the few foreigners living on the street came from respectable stock; they were Germans, Englishmen, Irishmen, and Scotsmen, not the Poles or Russians or Greeks who filled so much of the east side. Some of them were native Detroiters, and virtually all the rest had come to the city from other northern states, so they knew how to make their way in the big city: they understood how to work their way into the trades, how to use a membership in the Masons or the Odd Fellows to pry open employment-office doors, how to flash a bit of fast talk to sway a reluctant buyer.8

Such advantages helped the people of Garland find solid jobs, a blessing in a city that burned through workingmen, then tossed them aside. A minority of the men worked as salesmen, teachers, and shop clerks, the sort of jobs that didn’t pay particularly well but kept the hands clean. A few more were craftsmen, the elite of the working class, trained in metal work or carpentry or machine repair and fiercely proud of the knowledge they carried under their cloth caps. Many more had clawed their way to the top rung of factory labor. They were foremen, inspectors, supervisors, men who spent their days in the noise and dirt of the shop floor making sure that others did the backbreaking, mind-numbing work required to keep shiny new cars flowing out of the factories.9

Most of the women worked at home. They rose early to make husbands and boarders breakfasts sufficient to steel them for a day of work, then bustled children off to school—the youngest to Julia Ward Howe Elementary, a brooding two-story brick building at the intersection of Garland and Charlevoix, three blocks north of Jefferson; the older ones to Foch Middle School and Southeastern High. Mornings and afternoons were spent shopping and sweeping and washing clothes streaked with machine oil and alley dirt. Their evenings were devoted to cooking and cleaning dishes while their husbands relaxed with the newspaper or puttered out in the garage.

No matter how many advantages the families along Garland Avenue enjoyed, though, it was always a struggle to hold on. Housing prices had spiraled upward so fearfully the only way a lot of folks could buy a flat or a house was to take on a crippling burden of debt. The massive weight of double mortgages or usurious land contracts threatened to crack family budgets. Men feared the unexpected assault on incomes that at their best barely covered monthly payments: the commission that failed to come through; the rebellious work crew that cost a foreman his job; the sudden recession that shuttered factories for a few weeks. And now they faced this terrible turn of events: Negroes were moving onto the street, breaking into white man’s territory. News of their arrival meant so many things. A man felt his pride knotted and twisted. Parents feared for the safety of their daughters, who had to walk the same streets as colored men. And everyone knew that when the color line was breeched, housing values would collapse, spinning downward until Garland Avenue was swallowed into the ghetto and everything was lost.10

*

Word that a colored family had bought the bungalow on the northwest corner of Garland and Charlevoix had first spread up and down the street in the early days of summer. The place was kitty-corner to the elementary school and directly across Garland from the Morning Star Market, the cramped neighborhood grocery where many of the women did their daily shopping. The rumors had caused a lot of consternation, much tough talk, and some serious threats. But most people were still surprised when, the day after Labor Day, policemen took up positions around the house.11

The Negroes had arrived in the morning, half a dozen of them. Since they didn’t have much furniture, they’d finished the move in no time at all. But the police had stayed all day and into the night. They returned first thing the next morning. A couple of patrolmen wandered listlessly back and forth along the blistering sidewalk as school let out at 3:15. An even larger official presence was in position—eight officers stationed around the intersection—when the men came home from the factories a few hours later.12

Garland wasn’t a friendly street. Neighbors might nod as they went to work, chat in line at the market. Kids might play together. But there were a few too many transients—a young couple renting out a flat, a single man boarding in a back bedroom—for folks to really feel connected to one another. Even longtime residents generally kept to themselves.

On the evening of September 9, 1925, though, neighbors couldn’t wait to get outside. Partly, it was the soaring temperatures that drew them down to the street. But it was the pulsing energy, the surging excitement that really tugged at them. The Negroes were nowhere to be seen; there were no lights burning in the bungalow, no sign of movement anywhere on the property. But everyone knew they were in there. And everyone knew that the police were stationed out front because there might be trouble.13

So people finished up their suppers and, one by one, drifted out to Garland. It was close to seven when Ray and Kathleen Dove brought their baby daughter onto the porch of their flat, almost directly across from the colored family’s house. Ray had spent the day in the Murray Body plant, up near the Ford factory, where he worked as a metal finisher. It was a sweaty, dangerous job, grinding down the imperfections in steel auto bodies, making them as smooth as customers expected them to be. As usual, Ray came home anxious for an evening of relaxation. Kathleen sat in the chair she brought outside and Ray leaned against the railing, watching the baby play at his feet. Their two boarders, George Strauser and Bill Arthur, soon joined them. Strauser kept himself occupied by writing a letter. Arthur, only three days in the neighborhood, was content to sit with his landlords and pass the time while the sun slowly set.14

As they chatted, the sidewalk in front of the Doves’ house began to fill up with excited neighborhood children. Thirteen-year-old George Suppus dragged his little brother down the street as soon as they had finished their after-dinner chores. He met his best friend, Ulric Arthur, in front of the market. The three boys stood around for a while, watching the corner house, until a cop told them to move on. Then they wandered over to the Doves’ front lawn, where no one seemed to care how long they loitered.15

Most adults wouldn’t admit to sharing the kids’ curiosity, so those anxious to be outside fished for excuses. Leon Breiner, a foreman at the Continental Motors plant, lived a dozen houses north of the Doves, in a frame cottage much more modest than the bungalow the Negroes had bought. He had good reason to stay at home: his wife, Leona, suffered from a heart condition and the heat left her drained and often cross. But Breiner grew restless sitting alongside her in the rockers they had on their small front porch, and he volunteered to pick up a few items from the Morning Star Market down at the corner. Puffing on his pipe, he headed down toward the police.16

Otto Lemhagen arrived at the corner shortly after seven to spend some time with his brother-in-law, Norton Schuknecht, a man of stature, an inspector in the Detroit Police Department, commander of the McClellan Avenue Station. This was all very impressive to Lemhagen, who in his career had risen all the way to investigator at the telephone company. Garland lay within Schuknecht’s precinct, so Lemhagen knew his brother-in-law would be spending the evening out at the coloreds’ house, making sure nothing untoward happened. Lemhagen sidled up to him while he stood kitty-corner from the bungalow, chatting with his lieutenant.

While the two men passed the time, Garland took on the feel of a carnival. Traffic was growing heavier, and there were knots of people in the school yard—maybe twenty, thirty people, or more—mostly women and children. Some sat on the lawn. A few tossed a baseball around on the gravel playground. More neighbors meandered up and down Garland or Charlevoix, sometimes alone, other times in small groups, although Schuknecht’s patrolmen weren’t allowing any of them onto the sidewalk directly in front of the Negroes’ house. There was an air of good humor on the corner, an easy sociability that Garland Avenue rarely experienced. People talked about mundane matters: the weather, their summer vacations, the new school year. But Lemhagen also caught snatches of bitterness seething through the growing crowd. “Damn funny thing,” he heard someone on the school yard say, “that the police wouldn’t go in there and drag those niggers out.”17

Eric Houghberg felt that same mix of bonhomie and anger as he made his way home from work a few minutes later. The twenty-two-year-old plumber—an angular young man, with ears too large for his long, thin face—rented a room in the upstairs flat next door to the Doves. He knew that the Negroes’ presence riled people. Hadn’t his landlady greeted him at the door yesterday afternoon with the taunt, “You got new neighbors over there. That’s the nigger people. That’s the people trying to move in over there.” Houghberg wasn’t the sort of man who went looking for trouble. But he couldn’t resist the pull of the street, the chance to break his routine, to share the warm night air with people like himself. So he rushed upstairs to grab a bite to eat and to clean up: a quick wash, a shave, a new set of clothes. It was a bit of vanity, that’s all. He wanted to wipe away the grime of the day, to look his best.18 Who knew what might happen on a night like this?

*

By 5:30, the late summer sun was already starting to sink toward the row of tightly packed houses. The light that had been filtering through the drawn curtains began to fade. But the gathering darkness did nothing to dissipate the heat that had built up over the course of the day. With the windows barely cracked open and the doors shut fast, the bungalow on the corner was enveloped in a suffocating stillness.

Dr. Ossian Sweet sat at the card table he’d set up in the dining room. He was a handsome man, short, dark, and powerfully built. A month short of thirty, he looked ten years older: his hairline was receding, his waistline was expanding, his face was taking on the roundness of middle age. Other men might have hated to see their youth slipping from them. Sweet cultivated the illusion of maturity. Where he came from, black men were permanently “boys,” never worthy of white men’s respect, never their equals. Dr. Sweet was no boy. He was a professional man, better educated, wealthier, more accomplished than most of the whites he encountered. He wanted others to know it the moment they saw him. So he favored tailored suits, well cut and subdued. He bought crisp white shirts and tasteful ties. He wore the round, tortoise-shell glasses popular with college men. He kept his mustache neatly trimmed, his hair stylishly short.19

Sweet attempted to project the casual confidence, the instinctual authority that set doctors apart from the ordinary run of men. It didn’t come to him naturally. As a child, he had shared in the backbreaking work of his parents’ Central Florida farm, tending the fields his father rented, hauling water from the stream so that his mother could do the laundry, caring for the ever-growing brood of brothers and sisters who filled every cranny of the tiny farmhouse his parents had built by hand. His mother and father had taught him what they could, immersing him in the religious traditions that had sustained the family through generations of struggle, making him want to succeed. Then, when he was thirteen years old, they had sent Ossian away, not because they wanted one less mouth to feed, though lifting that burden was a blessing, but because they loved him. Get away while you’re young, they told him. Go north. Get an education.

And he did, though he left Florida with only as much as he could glean from six years in a one-room schoolhouse that shut down when harvest time came. It took him twelve more years to fulfill his parents’ instructions, a dozen long, hard years of schooling to master the material that would make him an educated man and earn the pride that was expected of the race’s best men, all the while working as a serving boy for white people—washing dirty dishes, waiting tables, carting luggage up hotel stairs—just to pay tuition and buy the books his professors required him to read. Ossian never excelled, but he got an education, as fine an education as almost any man in America, colored or white, could claim. By age twenty-five, he had earned his bachelor of science degree from Wilberforce University in Ohio and his medical degree from Washington, D.C.’s Howard University, the jewel in the crown of Negro colleges.

He’d come to Detroit in 1921 with virtually nothing, but in the four years since then he’d built a thriving practice down in Black Bottom, the city’s largest ghetto; he’d earned the respect of his colleagues at Dunbar Memorial, the city’s best colored hospital; he’d helped his brother Otis launch his professional career. Best of all, Ossian had found in his wife, Gladys, a young woman of grace, charm, and social standing, a wonderfully suitable doctor’s wife. As a gift to them both—and a balm for their pain—Ossian had taken his bride on the sort of adventure one reads about in novels: a year-long stay in Vienna and Paris, where he completed postgraduate studies on the cutting edge of medical science.20

Yet, despite all those victories, Ossian remained, deep down, the frightened Florida farm boy trying to carry his family’s expectations on his narrow shoulders. He didn’t doubt his abilities; he knew he was a fine physician, better than most. But he often tried too hard to impress—to find just the right phrase, to strike just the right pose, to keep just the right distance—to reassure himself. Now, as the darkness slowly descended around him, his carefully constructed veneer crumbled away. He didn’t feel sure of himself. He felt terribly, terribly afraid.21

This house was supposed to have been one more grand accomplishment. Ossian and Gladys had first seen the bungalow in late May 1925. She loved it from the start. A city girl, born in Pittsburgh, raised in a small but comfortable house in Detroit only a few miles north of Garland, Gladys knew quality when she saw it. She’d desperately wanted a home with a yard, where Iva, their fourteen-month-old daughter, could play. This house had much more to offer as well. The first-floor brick still had the sharply defined edges of new construction; the shingles above were newly painted. The front porch, shaded by the sloping roof, looked so cool and inviting, Gladys could imagine long evenings there, sitting on the swing, talking and reading.22

The interior was, if anything, even more attractive. The original owner, a Belgian-born contractor by the name of Decrudyt, had built it for his family, and he obviously had wanted the best. The first floor had the cool elegance of the arts and crafts style. Polished oak trim framed the long living room and the dining room behind it. Solid squared pillars stood on either side of the archway that divided the two rooms. A built-in hutch—glass-fronted doors above, generous drawers below—dominated the dining room’s far wall; on the opposite side of the room, small built-in bookcases, nestled into the base of the pillars, echoed the effect of compact craftsmanship that the hutch created. Gladys reveled in the small touches: the flower pattern on the decorative tiles surrounding the gas fireplace in the living room, the leaded-glass windows on the south side, the stylish chandelier hanging low in the dining room, the small alcove that extended from the same room. This would be the place to put the piano she envisioned them having, the place where she could re-create the music that had always filled her parents’ home.23

Gladys had been thrilled by the spaciousness, so welcome after months of making do at her mother’s house. Truth be told, she was pleased that her home had one more room than her mother’s; she was moving up, ever so slightly, the way the next generation was supposed to do. Iva could have her own room. She and Ossian would take the front bedroom, overlooking Garland, for themselves. It was small, barely big enough for a bed and a dresser. But they’d get the morning sun streaming in through the three dormers and they’d avoid the late-night noise on Charlevoix, where the streetcar ran.24

Ossian also liked the house, maybe not for the stylish touches—though he was a stylish man—but for the message the house delivered. Most Negroes lived in Black Bottom on the eastern end of downtown Detroit. When he first came to the city, Ossian had lived there himself. But established physicians—doctors with solid practices and families to raise—almost always lived in better neighborhoods, and Ossian wanted nothing less for his young family. He deserved a home such as this, the newest, most impressive house on the block.25

But Ossian also saw the dangers he would be facing if they moved here. He had already seen what white men could do, and sometimes the memories grabbed hold of him. He could see himself as a small boy again, listening to the terrifying stories of colored men mutilated and murdered at the phosphate pits just outside his hometown. With terrifying clarity he could still see the mob of whites, hundreds and hundreds of them, gathered around that black boy, Fred Rochelle, the one who lived a few blocks from the Sweet family, who had been accused of raping a white girl. He could pick out individuals amid the throng, ordinary people from the white side of town—the jeweler, the livery owner, the butcher—their faces alight with anticipation as they waited for the moment when the torch met the pyre and the flames began to lick at Rochelle’s battered body. Then the memories flashed to another time, another place, so far from Florida and yet so similar. Ossian could see the gangs of white soldiers and sailors roaming the streets of Washington, D.C., the summer after the war, looking for Negroes to maim and kill, marching up Seventh Street toward Howard University, toward the medical school, toward Ossian himself. He could see them coming for him.26

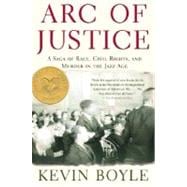

Excerpted from Arc of Justice by Kevin Boyle.

Copyright © 2004 by Kevin Boyle.

Published in 2004 by Henry Holt and Company.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.