Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

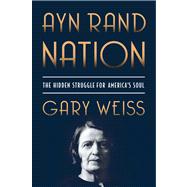

Gary Weiss is a journalist and the author of two books probing the underside of finance, Wall Street Versus America and Born to Steal. He was an award-winning investigative reporter for BusinessWeek, and his articles have appeared in Condé Nast Portfolio, Parade magazine, Salon, and The New York Times, among other publications. He lives in New York City.

"Think Ayn Rand is marginal? Think again! Gary Weiss's powerful new history inscribes the libertarian firebrand at the very center of the American story of the past three decades. "--David Frum, NY Times bestselling author of The Right Man and Comeback

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.