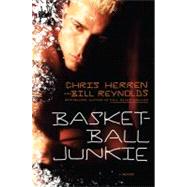

CHRIS HERREN is a former NBA basketball player for the Denver Nuggets and the Boston Celtics. His company, Hoop Dreams with Chris Herren, Inc., provides basketball training for young players as well as educational talks. He lives in Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

Chris Herren is the founder of Hoop Dreams with Chris Herren, a basketball player development company; the author of Basketball Junkie; and a public speaker with the American Program Bureau.

BILL REYNOLDS is a sports columnist for The Providence Journal and the author of several previous books, including Fall River Dreams and (with Rick Pitino) the #1 New York Times bestseller Success Is a Choice. He lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.