Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

It was raining and still dark when I got to the barn.

The barn was located behind the Oklahoma training track at Saratoga Race Course.

Saratoga is in upstate New York. The training track had been named in the early years, when people had to walk rather than drive to reach it, and its distance from the main track made it seem as remote as Oklahoma.

I squished through the mud, amid dark silhouettes of horses. It was 6 A.M. on the Monday of the last week of July 2003 -- the first week of Saratoga's six-week racing season. It also was the first time in more than thirty years that I'd been in the Saratoga stable area.

"Can I help you?"

"I'm looking for Mr. Johnson."

"What the hell for?"

The voice was like sandpaper. The speaker was a short man with rounded shoulders. He was wearing a rain jacket and baseball cap, and standing, stooped, beneath a wooden overhang in front of a stall about halfway down the shed row. I hadn't seen him since 1971, and I hadn't actually met him even then, but I knew this had to be P.G.

"I called you last night," I said. "You told me I could meet you here this morning."

"Why would I have said that? Oh, Christ, you must be the guy I'm supposed to be nice to so my daughter doesn't lose her goddamned job."

I could hardly see him in the dark, through the rain.

"If you have any questions," he said, "I'll try to answer them. If it's not inconvenient, I might even tell you the truth. But I hope you don't have too many. Ocala's my assistant, but don't bother him, he's a son of a bitch. And try to stay out of the way. I'm a working horse trainer, not a goddamned tourist destination."

He turned, and started to shuffle back toward the end of the barn, to the small, dirt-floored cubicle that served as his office at Saratoga.

"I wanted to meet you thirty-two years ago," I called after him.

"You're late."

"The first time I ever bet a hundred dollars was on a horse of yours. 1970. It was the day of the Travers. Cote-de-Boeuf. Jean Cruguet rode him. Four to one in the morning line. He finished out of the money."

"You shouldn't bet. I quit that foolishness years ago."

"Later on, can I see Volponi?"

"Yeah, but for Christ's sake don't try to pet him, unless you want to start typing with your toes."

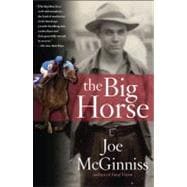

Copyright © 2004 by Joe McGinniss

Chapter Two

I was born in New York City in 1942, the year P. G. Johnson bought his first horse. My father's father, an MIT graduate, had been an architect in Boston. My mother's father, an Irish immigrant, had been a New York City fireman. Given such a disparity in bloodlines, if they'd been Thoroughbred horses, my parents would not have been bred to each other. As it was, the results were problematic.

We lived in an apartment in Forest Hills, Queens. My father -- who had lost both his parents in the influenza epidemic of 1918, when he was two -- was not a physically active man, but he did enjoy listening to sporting events on the radio.

I remember Red Barber describing Cookie Lavagetto's two-outs-in-the-ninth pinch-hit double off the Ebbets Field right-field wall that not only gave the Brooklyn Dodgers a stunning 3-2 victory, but deprived Yankees pitcher Bill Bevens of the first no-hitter in World Series history. That was in 1947, when I was four.

I also remember my father and I listening to Clem McCarthy's call of the 1948 Kentucky Derby, won by Citation, Eddie Arcaro aboard, with Calumet stablemate Coaltown finishing second.

My father -- who had attended MIT, but had not graduated -- did well enough in his business of preparing blueprints for New York City architects to enable us to move to a new home in Rye, in Westchester County.

There, on black-and-white TV, I not only saw Bobby Thompson's home run in 1951, but I watched Dark Star beat Native Dancer in the 1953 Kentucky Derby. I also remember seeing Nashua beat Swaps in the 1955 match race at Chicago's Washington Park (the biggest, it was said, since Seabiscuit vs. War Admiral), and being aghast when Willie Shoemaker misjudged the finish line aboard Gallant Man and lost the 1957 Kentucky Derby. Tom Fool, Bold Ruler, Round Table, Sword Dancer: These were heroes of my childhood sporting universe on a par with Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, and Jackie Robinson.

Eventually, my father took me to baseball games at Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds, and to Fordham University football games, but never to the races. My mother explained that no matter how splendid the Kentucky Derby might have seemed on television, the racetrack was a sordid place, populated by men even more disreputable than those who frequented taverns, or, to use her term, "gin mills." I was to follow my father's example and give both places a wide berth when I grew older. In response, I developed an extravagant fantasy life, in which I lived in a gin mill next to a racetrack, dividing my time equally between them.

That my father might have had more personal knowledge of either barrooms or racetracks than he let on was not something that occurred to me until one day -- I must have been about ten at the time -- when I spotted, among the many thick tomes on architectural history and design theory that filled the bookshelves of his study, a slim volume titled Win, Place and Show.

I took it down and began to read it, paying special attention to the portions my father had already underlined. It was not a long book, nor was it unduly complex, and I soon came to understand that the attainment of almost limitless wealth was well within the grasp of any horseplayer who learned to apply the author's handicapping and wagering principles.

My mother found me before I could finish it. She grabbed the book from my hands as if it was an illustrated edition of Peyton Place.

"Where did you get that?"

I pointed to my father's study.

"Well, I'll be speaking to him about that!" She walked off with the book under her arm and I never saw it again. Nor did my father and I ever discuss the incident. There was a lot that we never discussed.

As a result, the racetrack -- any racetrack -- came to seem the most alluring destination on earth. I vowed to visit one on my own, as soon as I was old enough to take the train into New York City and to ride the New York subway by myself.

This happened when I was twelve. I went to Jamaica Race Track, in the borough of Queens. You were supposed to be twenty-one to bet, but I was tall for my age.

Jamaica closed in the late fifties, but by 1959, as a senior in high school, I was cutting afternoon classes in order to go to the new Aqueduct, farther out in Queens, near JFK Airport, which was named Idlewild at the time.

I made my first trip to Saratoga in August 1962, for the Travers Stakes. Jaipur beat Ridan by a nose. A lot of people don't realize that Jaipur never won another race -- which is neither here nor there, but it's the sort of useless thing you remember from having spent a lot of time around the track.

For a while -- stuck in college in central Massachusetts -- I became a regular at such sorry venues as Suffolk Downs in Boston and Lincoln Downs and Narragansett in Rhode Island. I lost money on horses that were, on their best day, Thoroughbreds in name only, and I didn't see many on their best day.

During vacations, I moved up in class. I got to Hialeah in the winter, Garden State and Pimlico in the spring, and Saratoga and Monmouth in the summer. By the time I graduated -- which was a closer call than it should have been, in large part because I'd spent more time with the Morning Telegraph and Daily Racing Form than with my textbooks -- I'd probably been to every Thoroughbred horse-racing track north of the Mason-Dixon Line and east of the Mississippi, and to quite a few that lay beyond.

In 1963, I hitchhiked to Louisville for the Kentucky Derby, snuck in through the stable entrance before dawn, and with my last two dollars made the most wonderful bet of my life -- on Chateaugay.

Ridden by the magisterial Panamanian Braulio Baeza, Chateaugay beat the three favorites -- Candy Spots, No Robbery, and Never Bend -- and paid $20.80 to win.

In those days, there were two races on the Churchill Downs card after the Derby. I parlayed my Chateaugay profit and won them both. That night, I booked a suite at the Brown Hotel, which was as fancy as you could get in Louisville in the early sixties, and entertained a lovely secretary from Fort Wayne. The next day, instead of hitchhiking back to Massachusetts, I flew first-class on Allegheny.

But after that, my life at the track was mostly downhill. Once out of college, I broadened my range to include not only Chicago's Arlington Park, but even Hollywood Park and Santa Anita in California. All too often, however, and with excuses that grew flimsier over time, I found myself at such forlorn locales as Pocono Downs, Yakima Meadows, and Ak-Sar-Ben (and what else could they do with a racetrack in Omaha except name it for Nebraska spelled backward?). I went to the track wherever I was, and where I was was too often the result of there being a track in the vicinity. In December 1967 -- a month before the Tet Offensive -- I even went to the races in Saigon.

Through it all, Saratoga remained a beacon. It was the promised land: Camelot, or Xanadu, where the breezes were fresh, the horses fast, and the women beautiful. And where one's bankroll would magically replenish itself overnight.

I think it is safe to say that Saratoga has been written about more than all other American racetracks combined, and almost always in a reverential tone. Through the 1950s and 1960s, I read a lot of that writing and it did much to shape my perception of the place, even if my clearest memory of the 1962 Travers was of how crowded it had been, and how nearly impossible it was to see the race.

I knew Red Smith's famous directions for reaching Saratoga from New York City: Take the Thruway north for 175 miles, get off at Exit 14, turn west on Union Avenue, and go back a hundred years in time. And I believed, with his Herald-Tribune compatriot, Joe Palmer, that "a man who would change it would stir champagne."

Saratoga had been bathed in a special aura from the start. Already famed for having hosted one of the more significant battles of the Revolutionary War, as well as for its underground springs, which were said to have myriad medicinal properties, the town had developed into a posh summer resort (popular among "artificial aristocrats," a local newspaper said) even before Thoroughbred horses began to race there, in August 1863.

At first, the racing served only as a minor diversion for high-stakes gamblers -- a way to pass the time between hangover and cocktail hour -- and most of the press attention it attracted was negative.

"Men shout and grow frantic in their frenzy as the horses whirl round the track," the New York Tribune wrote in 1865, "and as they close upon the goal the spasm becomes stifling, ecstatic and bewildering."

As if that was a bad thing.

From the start, Saratoga was known for its short season (for decades, only four weeks in August), for the high quality of its horses, and for the inordinately high percentage of spectators with names such as Vanderbilt, Whitney, and Phipps.

Their presence -- in many cases, the high-quality horses belonged to them -- and their willingness to spend the money necessary to keep their private playground impervious to change were what provided Saratoga, for years, with its special ambience.

There were other notable racetracks in America -- and by the start of the 1970s, I probably had been to them all, except Keeneland in Lexington, Kentucky -- but for a concentrated commingling of old money and new horses in a pastoral setting, Saratoga was unmatched.

More than a hundred years earlier, the New York Times had described the scene as consisting of "pure air, fresh breezes...[and] a great deal of very weak human nature." Those still seemed the perfect ingredients for a summer vacation, especially with good horses to spice the blend. In 1971, having finished a novel set at Hialeah, I tried to arrange such an interlude for myself, signing a contract with Alfred A. Knopf Inc. to write a book about that season's racing at Saratoga.

At the start of August, I moved into a rented house on the outskirts of town with a well-traveled but persistently unlucky trainer named Murray Friedlander. Murray was the first person I'd ever known who garnished a dry martini with a garlic clove. He was also the first man -- and last -- I ever met who could drink champagne for breakfast and then proceed to have a productive working day.

It was Murray who suggested that I seek out his colleague P. G. Johnson. He said he'd known P.G. for years, since they were both scraping by in Chicago, and that there was no finer man in the game, nor one who would be better able to help me penetrate the Fortune 500-cum-Social Register veneer that lay atop Saratoga like the early morning fog. Murray warned me that P.G. could be prickly, and that he didn't suffer fools, gladly or otherwise, but Murray also said he knew the game intimately at every level, and that unlike many of his famously taciturn colleagues, P.G. could and would talk about it.

I'd never met Johnson, but I'd been aware of him since he came east from Chicago in 1961. He was the leading trainer at Aqueduct that fall, his first in New York, which was the equivalent of a ballplayer just up from Triple A leading the league in batting in his rookie season in the majors.

And though we didn't meet, he and I both attended the 1970 Kentucky Derby. He'd entered a horse called Naskra, and stirred a bit of Vietnam-era controversy by attaching a peace symbol to the horse's bridle. I was tempted to bet on Naskra to show support for the gesture -- and because Chateaugay's jockey, Braulio Baeza, was riding him -- but, in keeping with my notoriously poor judgment, I put my money on Corn off the Cob. Not that it mattered: Naskra ran fourth, with Corn off the Cob well behind him.

But before I could contact P. G. Johnson at Saratoga, I learned that my father had a brain tumor and that immediate surgery would be required. I left the next day. The tumor was malignant. My father died. He was 56. I never did ask him about Win, Place and Show.

By the time I got back to Saratoga to write about it, I was sixty. It hadn't occurred to me that P. G. Johnson would still be there.

Copyright © 2004 by Joe McGinniss