Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

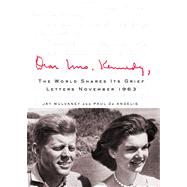

JAY MULVANEY, the author of Kennedy Weddings and Diana and Jackie and an Emmy Award--winning writer and producer, was once an office boy for Senator Edward M. Kennedy.

PAUL DE ANGELIS has been an editor, editorial director, and editor-in-chief at such publishing companies as St. Martin’s Press, E. P. Dutton, and Kodansha America.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.