Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

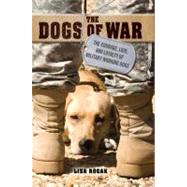

“Lisa Rogak’s The Dogs of War sheds light on why the dog, more than any other animal, holds a special place in our history, and our hearts. The most comprehensive book I have ever read on the subject of military dogs, it exemplifies the indomitable spirit of the dog itself, ever selfless, loyal to a fault.”

--Steve Duno, author of Last Dog on the Hill

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.