Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

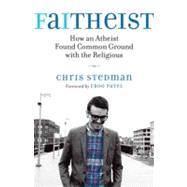

Chris Stedman is the Assistant Humanist Chaplain at Harvard University, the emeritus managing director of State of Formation at the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue, and the founder of the first blog dedicated to exploring atheist-interfaith engagement, NonProphet Status. Stedman writes for the Huffington Post, the Washington Post’s On Faith blog, and Religion Dispatches. He lives in Boston.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.