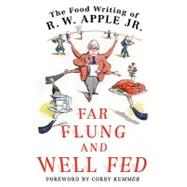

R.W. APPLE JR. worked for The New York Times for forty years, serving at various times as Associate Editor, Chief Correspondent, Chief Washington Correspondent, and Washington Bureau Chief. He began writing food articles for the Times in the late 1970s, when reporting from London. His writing also appeared in a variety of magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, GQ, Saveur, Travel & Leisure, Departures, Gourmet, Town & Country and National Geographic Traveler. He lived with his wife Betsey in Washington, D.C, where he died in 2006.

CORBY KUMMER is a Senior Editor at The Atlantic Monthly, where he also writes extensively about food, and is the author of The Joy of Coffee and The Pleasures of Slow Food. He lives in Boston, where he is a five-time winner of the James Beard Foundation’s Journalism Award, including its MFK Fisher Distinguished Writing Award, for his Atlantic columns.

The Glorious Summer of the Soft-Shell Crab

The sun was a blood-orange disk pinned to the horizon as Thomas Lee Walton eased his 24-foot Carolina Skiff into the creek and headed toward the Rappahannock River. An osprey was perched in a dead tree on the far shore. It was 6:05 a.m. We were going crabbing.

Our quarry was the Atlantic blue crab—Callinectes sapidus to marine biologists, which means “savory beautiful swimmer” in Latin. But not the run-of-the-mill fellows you boil up with plenty of Old Bay seasoning, then crack with a hammer before pulling out the sweet, delicate white meat. Mr. Walton fishes for “busters” or “peelers,” which are crabs that have already begun to shed their shells, or are about to, before growing new ones.

“Watching them shed,” Mr. Walton said with a tender reverence suprising in a rugged outdoorsman, “it’s like they’re reborn.”

If you catch them at the right moment and pull them from the water, the process of growth stops and you have a soft-shell crab, one of summer’s most prized treats, not only here on the rim of the Chesapeake Bay, but also, increasingly, in cities across the United States.

They seem to be on every menu in New York this summer, prepared in more or less the same way: You eat the whole thing, claws, legs and all, sautéed or grilled, maybe seasoned with a squeeze of lemon juice. Before you try one, it sounds decidedly dubious, like tripe or seaweed. But a single taste makes a convert.

Years ago, I served a soft-shell, grilled in my garden, to Paul Bocuse, who formed a wildly inflated view of my cooking skills as a result. Soft-shells can be deep-fried, too, which makes them crunchier, and good ol’ boys like to stick them between two slices of white bread to make sandwiches. Me, I prefer my soft-shells sautéed, because I think the crust masks the flavor.

All crabs molt, up to 20 times during their lives; they must do so to grow. But the soft-shell form of the Dungeness crab on the Pacific Coast or the king crab in Alaska is seldom eaten, if ever, and Europeans use soft-shell crabs mostly for bait. In this as in so many things gastronomic, the Venetians are an exception. They consider Mediterranean shore crabs that have shed their carapaces, which they call moleche, a great delicacy.

Even here, where soft-shells have been savored for more than a century, putting them on gourmands’ tables is a dicey proposition, requiring luck, hard physical labor and painstaking attention to detail, in roughly equal proportions. Nobody has found a way yet to farm crabs. Mr. Walton and his fellow watermen, as they call themselves, must catch peelers in wire-mesh traps, take them ashore, transfer them into shallow seawater tanks and check each one carefully every six hours around the clock, waiting for them to shed their shells.

The crabs, elusive and pugnacious, don’t make it easy.

In William W. Warner’s fine book about crabs, Beautiful Swimmers (Little, Brown, 1994), he quotes a splendid triple-negative aphorism he heard from a waterman on Mary land’s Eastern Shore: “Ain’t nobody knows nothing about crabs.” Mr. Walton agrees, steeped though he is in crustacean legend and lore. “Catching crabs is mostly instinct,” he said.

“Every time you think you’ve got them figured they change on you,” he added, standing at the tiller of his boat, bronzed from a summer’s work. “We try to outthink them, but they don’t think. They just react to changes in the water, little changes in chemistry that we don’t understand.”

He put in a fresh wad of Red Man chewing tobacco and squinted into the sun, looking for the buoys that marked one of his lines of traps.

Mr. Walton’s family has lived and worked on the water for generations—how many, he could not say. They moved to Urbanna from remote Tangier Island, out in the bay, after a terrible hurricane in 1933. They have been here ever since. He, his brothers, his uncle, his aunt and his son, Lee, are all crabbers, all true Tidewater folks who pronounce “about” not at all like the rest of us, but about halfway between uh-BOAT and uh-BOOT.

Jimmy Sneed is what the Walton family and their neighbors call a “come-here”—someone from somewhere else. But after almost a decade he has won their confidence, and they have taught him most of what they know about soft-shells, which is one reason his restaurant in Richmond, the Frog and the Redneck, may serve the most delectable soft-shells anywhere.

Bearded, ribald, shod day and night in one of his 14 pairs of Lucchese boots, Mr. Sneed is (and is not) the redneck in his restaurant’s name. It comes from a moment of comic conflict more than a decade ago, when he was working for the French chef Jean-Louis Palladin, then the proprietor of Jean-Louis in Washington and now installed at Palladin in Manhattan.

As Mr. Sneed tells the story, Mr. Palladin was shouting at him, not for the first time, and Mr. Sneed snapped. “Shut up, you stupid frog,” Mr. Sneed shouted back. Mr. Palladin whirled, glared, slammed his knife on the counter and demanded, “What did you call me?” When Mr. Sneed repeated the epithet, Mr. Palladin yelled, “Then you must be a…a redneck!”

He isn’t, of course, though he sometimes relishes the role; the son of a Veterans Administration administrator, he grew up in a dozen towns and cities, including Charleston, S.C., and Peekskill, N.Y. Of course, Mr. Sneed and Mr. Palladin became close friends. And of course, when Mr. Sneed decided to move to Richmond after five years of running a restaurant in Urbanna, he could not resist naming his new place in honor of his mentor.

Crab has become Mr. Sneed’s metier. Every night of the year, he serves a rich, red pepper cream soup garnished with crab, as well as ethereal crab cakes, made of prime backfin lump crab meat, bound together with little more than a dab of mayonnaise and the chef’s prayers. He serves them even when crab is so scarce, as it is right now, that he has to charge $32.50 for them to make a profit. When soft-shells are in season hereabouts, from May until mid-October, he serves them, as well.

Mr. Sneed buys mostly from Thomas Lee Walton, who saves the softest of soft-shells for him. These are the ones that have been culled from the tanks within a half-hour of molting. (The tanks are called “floats” by the watermen because in the early days of the industry they were slatted boxes floating in the creeks.)

The new crab shells begin to form at once, and because the watermen can’t hover over the tanks, they get only a fraction of the soft-shells at the optimum moment. These are called “velvets” in the colorful terminology of the crabbers. Plump and bursting with salty-sweet flavor, they are also very fragile, so Mr. Sneed, his wife or his daughter drives to Urbanna every other day, a two-and-a-half-hour round trip, to fetch them at the source.

“Soft-shells are very important to us,” Mr. Sneed told me in a rare outburst of understatement. “And you have to try for the premium raw materials, no matter how much trouble it is. Product is king.”

A self-described culinary minimalist, Mr. Sneed cooks the crabs in the simplest way imaginable. He pulls them from the refrigerator, dusts them with Wondra flour, which is milled extra fine so that it doesn’t clump, and slides them, shell side down, into a heavy cast-iron frying pan filled to a depth of a quarter of an inch with a 50-50 mix of canola oil and drawn butter. After 60 seconds, he turns them and cooks them 30 seconds on the other side.

“Careful,” Mr. Sneed warned. “When soft-shells are really fresh, they’re full of salty water, so they tend to pop and burn you.”

And don’t serve them with tartar sauce, not unless you want to make the nonredneck see red.

It took the watermen many years to make the discovery that put the soft-shell trade on a sound commercial footing. Finding a buster in a pot or along the shore is a relatively rare occurrence. They needed some means of forecasting when other crabs were about to molt, so they could take it ashore and wait for it to do its thing. Finally, some unstoried hero noticed that on the next-to-last section of the articulated swimming leg, the most translucent part of the crab, a white line that later turns pink, and finally an intense dark red, can be detected when a crab is about to shed its shell.

It can be detected, that is, by an experienced waterman like Mr. Walton. I could just barely make out the line at its cherry reddest, when the crab was an hour, maybe minutes, from molting, but the rest of the time I couldn’t break the code, no matter how closely I looked.

The crabs with white lines, known for some reason as “greens,” shed in two weeks; those with pink lines, sometimes called “ripe,” will molt within a week; and the red liners, termed “rank,” will need a day.

In fact, the telltale lines are the edges of new shells, or exoskeletons, forming inside old ones in anticipation of molting.

I marveled at Mr. Walton’s skills. When we arrived at the traps, or pots, that he had set out along the northern shore of the Rappahannock estuary, he chugged up to the first, set the tiller so it kept the boat tracing a circle around the pot and put on an oilcloth apron and two pairs of gloves. Then, with practiced grace, he snagged the buoy with a boathook and pulled up the line attached to it, hand over hand, heaving the pot into the boat until it broke water.

The pot is a cube-shape contraption with three conical entrances, which crabs can swim into but not out of. In the first one were a half-dozen crabs, as well as a croaker and an alewife, as menhaden are called hereabouts. Mr. Walton undid the latch and dumped the catch onto a sorting table, then quickly pitched the fish and the hard-shells back into the water, closed the latch and lowered the pot.

Only five or six times all morning did he expend more than a passing glance in “reading” which crabs were peelers and which not. Most of the time, he instantly tossed the greens into one bushel basket at his feet, the ripes and ranks into another and the few busters into a blue plastic basin filled with river water so that they could continue to molt there. When he was unsure, he held the crab in question up to the sun, its claws a beautiful powder blue, studied it and pitched it in the appropriate direction.

On picking the right crabs on such slim evidence rests his livelihood. He makes few mistakes.

But if the crabs aren’t there, no crabber can catch them. Mr. Walton pulled about 70 good peelers and busters from his first line of 50 traps, but from the second and third, he got only about 10, and then he quit for the day. August is never the best month for soft-shells. That comes each May, when he usually takes five or six bushels of crabs off his boat at day’s end—about 1,000 to 2,000 crabs. The May catch is almost as big as those of all the other months put together.

At $1.50 each, the morning’s work grossed about $120. But out of that Mr. Walton has to pay for gas and the upkeep of his boat, his pickup truck, his pots (which cost $12 each) and his two dozen shedding tanks, which look like shallow plastic bathtubs. No formula for instant riches.

Is the overall crab catch in the bay and its tributaries shrinking, as the harvests of striped bass and oysters did in recent years, with disastrous economic consequences? Many watermen, and Mr. Sneed, think it is, and they blame winter crabbing with dredges, which pull hibernating crabs from the mud, along with laws permitting crabbers in Virginia to keep female crabs carrying a spongelike mass of eggs.

Not so, said Mike Osterling, the top crab expert at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at Gloucester Point, near Hampton.

“I’ve seen no records indicating a long-term decline in soft-shells,” he said. “Soft-shell fishing has its good days and bad, like anything else. But more people are going into the soft-shell business every day, all the way from here to Texas, and that’s no sign of a fishery in decline.”

Tradition says that the Chesapeake produces the best soft-shells, and I’m a great respecter of food traditions. But the season lasts a little longer farther south because of the warmer water, and I’ve eaten some pretty good soft-shells taken by fisherman in Louisiana and North Carolina, mostly small operators like the watermen on the bay.

As for Mr. Walton, he sells all the velvets he has to Mr. Sneed, and those with a slightly firmer shell, called “shippers,” he ships. Every so often, a refrigerated truck stops here, picks up trays of crabs covered with wet paper or eel-grass and heads north toward the big fish market at Jessup, Md., near Baltimore.

Sorted by size—whales are the biggest, spiders the smallest, with jumbos, primes, hotels and mediums in between—they go to a wholesaler named Louis Foehrkolb, whom Mr. Walton has never met. He keeps track of the shipments and sends Mr. Walton a check at month’s end.

I asked whether he ever worries about being shortchanged. “Nah,” said Mr. Walton, whose smile is as roguish as ever at 52. “I figure if he stops sending me money, I’ll stop sending him crabs.”

—Urbanna, Virginia, August 11, 1999

Tempura of Soft-Shell Crabs

(Adapted from the Frog and the Redneck, Richmond)

Time: 20 minutes

8 cleaned soft-shell crabs

1 cup flour

1¼ cups water

¼ teaspoon baking soda

2 ice cubes

Peanut oil for deep frying

Sea salt to taste

Yield: 4 servings

Roasted Ripe Tomato Salsa

(Adapted from Lucky Star in Virginia Beach, Va.)

Time: 1 hour, 20 minutes

10 plum tomatoes, halved lengthwise and cored

5 tablespoons olive oil

1 teaspoon herbes de Provence

Kosher salt and freshly ground pepper

3 ripe tomatoes, cored and diced large

3 shallots, peeled and julienned

1 yellow bell pepper, stemmed, seeded and diced medium

3 scallions, trimmed and sliced

1 teaspoon red wine vinegar

Yield: About 6 cups

Sauteed Soft-Shell Crabs

(Adapted from the Frog and the Redneck, Richmond)

Time: 20 minutes

1 cup flour

Salt and pepper to taste

8 cleaned soft-shell crabs

¾ cup clarified butter

½ cup canola oil

3 tablespoons lemon juice

1 tablespoon chopped parsley

Yield: 4 servings

In Bawlmer, Hon, Crab Is King

Baltimore is a quirky kind of town,” its former mayor Kurt Schmoke said not long ago. “Its heart is still working-class, even if the economic realities have changed. It is suspicious of anything elegant or stylish or pretentious. We have this world-famous educational institution, Johns Hopkins, in our midst, but it has never quite won the affection of ordinary Baltimoreans.”

You can see that spirit in the refreshingly unpompous local politicians, including the two senators, a tough, wisecracking Polish-American, Barbara Mikulski, and a reserved, cerebral Greek-American, Paul Sarbanes, as well as William Donald Schaefer, a wacky former mayor and governor who once settled a bet by diving into the seal pool at the National Aquarium. You can see it in the city’s sports heroes, gritty men like Frank Robinson, Johnny Unitas and Cal Ripken, who never blew their own horns.

And you can see it in the work of Baltimore’s favorite-son movie-makers, John Waters, who celebrated beehive hairdos, and Barry Levinson, who fondly explored the world of siding salesmen. Both like to set their films in their hometown, in what the iconoclastic Mr. Waters calls “this gloriously decrepit, inexplicably charming city.”

The standard form of greeting is “hon,” a term of endearment commemorated by a faux-’50s restaurant called Cafe Hon in Hampden, up north near the main Hopkins campus and the national Lacrosse Hall of Fame.

Baltimore’s eating habits are idiosyncratic, too. The city loves crabs, oysters and rockfish from Chesapeake Bay, which its poet laureate, H. L. Mencken, once described as “an immense protein factory.” It prefers diners and taverns tucked into venerable row houses to newer, trendier spots. It shops in the city’s old-fashioned covered markets, a half-dozen of them—the only places except the Ravens and the Orioles games where all of Baltimore comes together, blue-collar and blue-blooded, black and white, Greeks and Italians and Germans.

Crab is king. People here can’t live without their crab soup, their crab cakes and especially their spicy steamed blue crabs, which they rip open, split in two, crack with a wooden mallet and prod with a knife, excavating every last bite of sweet snowy meat with all the fervor of an Egyptologist opening a pharaoh’s tomb. In the winter months, when the big hard-shells—scientific name Callinectes sapidus, which means “savory beautiful swimmer”—are not available locally, the leading purveyors fly them in from ports in the South.

Unhappily, most visitors miss the best of Bawlmer eating. Taking the line of least resistance, they stop at the unfortunate mass feederies along the north side of the Inner Harbor, or at commercialized, gentrified crab houses like Obrycki’s, or in Little Italy. Marty Katz, a Baltimore photographer and food critic, dismisses the copycat restaurants in that neighborhood as “our versions of Mamma Leone’s.”

My nominee for the single best crab dish in Baltimore, if not the Western Hemi sphere, is the jumbo lump crab cake at Faidley’s Seafood in the Lexington Market, which was founded in 1782 and refurbished only recently.

You eat it standing up, at a counter or at a table with no chairs. Nancy Faidley Devine, 67, makes every one herself, including those she ships by mail, and last Christmas week she shipped 2,800.

“Other people handle the stuff too much,” she told me, “and it ruins the cake’s texture,” the same way that overworking sometimes toughens a pie crust.

In summer, Faidley’s crabmeat comes from packing houses in Wingate and Crisfield, Md., farther down the bay, and in winter it comes from Texas, Florida and North Carolina. Mrs. Devine won’t use imported crabmeat—“Pretty,” she said, “but no flavor”—and she won’t use pasteurized crabmeat, because it has a flat, metallic taste.

She said she watches carefully to make sure the meat contains plenty of yellowish “mustard,” or fat, which is as important to the flavor of a crab cake as marbling is to the flavor of a sirloin.

Faidley’s sells a crab cake made from claw meat for $4.50 and one made from backfin for $7.95, as well as the jumbo lump cake at $12.95. Each is seasoned differently and each has its virtues, but the costliest one, about the size of a slightly flattened Major League baseball, deep-fried to a golden turn, with crisp little hills and dales all around, is well worth the premium.

Delicate, delicious, creamy and sweet, it may not quite be heaven, but by my reckoning it’s a persuasive preview.

Mrs. Devine is canny about her recipe, except to say that it contains only a touch of Baltimore’s ubiquitous Old Bay seasoning, which can impart a harsh taste, plus broken saltines for body, mayonnaise, several mustards and spices. Her husband, Bill, 71, a retired naval officer who never lost the habit of salty talk, said the secret would die with his wife. “I sleep with her,” he added, “and she won’t tell me.”

It takes 20 minutes or so to drive to Dundalk, just east of the city line, where giant maritime cranes serve the docks, and the huge Sparrows Point mill spews out smoke and hot-rolled steel. The Costas Inn is there, a blue jeans and CAT hat tavern disguised as a crab house. Several of the Baltimore feinschmeckers I talked to said it serves the best steamed crabs in town, and it certainly impressed me.

You get the whole proletarian nine yards: Lots of good beer on draught, including amber-colored Pennsylvania-made Yuengling, from the nation’s oldest brewery; stacks of paper towels (not napkins) to clean up with; tables covered with heavy butcher paper; the spice-slathered crabs dumped unceremoniously in front of you from plastic trays.

And what crabs! Crab houses here describe size in terms of price, and the ones my friend and I ordered were 44’s, meaning they cost $44 a dozen. Huge brutes, heavy, full of luscious meat. Three each were plenty after a bowl of spicy Mary land crab soup, rich with vegetables. When we finished, our lips were stinging, our fingers were smeared with reddish gunk and a tumulus of shell and cartilage rose before each of us. Finger bowls were not provided.

Taverns, the prototypical Baltimore eating places, come in many varieties. Two of the best, in addition to Costas, are Duda’s, a laid-back bar facing the water in Fells Point, which serves what may be the best hamburger in the city, a plump disk of meat grilled to moist, deep-red perfection, and Henninger’s, a sweetheart of a back-street establishment in the same neighborhood, where I felt like a regular after two minutes.

Henninger’s décor is eclectic, to say the least, featuring old black-and-white publicity photos of strippers alongside a tapestry portrait of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. The food has ambition. When I stopped in, the menu included fried oysters on a bed of spinach with fennel and Pernod sauce, cooked by Jayne Vieth, and thin-sliced brisket of beef, deftly smoked by her husband, Kenny. The two of them own the little place.

Baltimore is a good breakfast town, too. Movie buffs should try the Hollywood Diner, a streamlined chrome beauty not far from the court house. This is where Boogie, Eddie, Fenwick and their friends, all of them afraid of growing up, hung out in the Barry Levinson classic, Diner (1982). Get there before 9 a.m. and you can have an egg and cheese on toast for only 99 cents.

If civilized talk and an unhurried session with the newspapers is your morning game, Baltimore provides City Cafe. The bagels are Manhattan-worthy, and the oatmeal is Ohio-worthy. Blue Moon, a hip cubbyhole all but impossible to get into on weekends, makes everything from scratch, including smoothies, cinnamon rolls and potato pancakes laced with bacon and green pepper. The scrapple is to die for: cut thin, fried crisp on the outside, molten on the inside. No easy thing to achieve, that.

In Helmand, Baltimore has the most unlikely of ethnic restaurants, an upmarket Afghan place, run by Qayum Karzai, brother of the Afghan head of state, no less. Its kaddo (sautéed pumpkin) and choppan (charcoaled rack of lamb) merit the raves they win from local critics year after year.

Attman’s is something else again in the ethnic line, a deli in business since 1915 whose corned beef—a bit grainy, a bit sour, not too salty—deserves to be mentioned in the same breath with New York’s best. You have to wait in a long line at lunchtime for Attman’s bulging sandwiches, Dr. Brown’s cream soda, half-sour dills and all-sour pickled onions. The 1100 block of Lombard Street is called “Corned Beef Row,” but most of it is a wasteland now, except for Attman’s and the slightly ersatz Lenny’s, whose Kelly green paint job gives it away.

I wish I could wax as enthusiastic about Baltimore’s famous pit beef. They serve it in joints on Route 40, the Pulaski Highway, a real boulevard of broken dreams, lined with cheap motels and shabby car lots. The beef is top round, dry-rubbed, grilled over charcoal, sliced thin, slapped into a kaiser roll and painted with horse radish.

My friend Calvin Trillin, down from New York, came along for a taste test. At Big Fat Daddy’s, a sullen kid served us drab, dried-out mystery meat that reminded me of boarding school. We found the sandwich at Big Al’s O.K., if not a tenth as enticing as the spiced beef sandwiches Chicago loves.

A busy port for more than 250 years, Baltimore has long had a sizable Greek population, which gathers at Samos, across from the Orthodox church on Oldham Street in East Baltimore. In this row-house neighborhood you see two of the other things that set the city apart: white marble steps called stoops and facades of Formstone, a cement-based falseface for porous brick.

Nick Georgalas presides in the kitchen at Samos. Tall, mustached, fierce-eyed, he looks like the partisan fighter that his father was, and he is one of those cooks who gives new life to culinary clichés. His grilled shrimp had too much dried oregano for me, but his dolmades, his souvlaki, his tsatziki and his grilled pita were worth much more than the modest prices asked.

The Black Olive in Fells Point, also Greek-owned, gets in trouble because its prices are high. Many people are reluctant to spend real money for Greek food (and Chinese food), which is a mistake. Owned by Stelios Spiliadis, whose brother runs Milos in New York, Black Olive is built around a display of fish from far and wide, which are presented atop a bank of ice: red snapper from the Gulf of Mexico, turbot from the North Sea, daurade from the Mediterranean, striped bass from the Chesapeake (which Mary landers call “rockfish,” supposedly because the best ones were once caught off the port of Rock Hall).

Simply grilled or pan-fried, dressed with a squirt of lemon and a few drops of best extra virgin olive oil, the fish is fabulous. So are the mezes, or starters, especially the chunky hummus and the olives, which are house-marinated in zaatar, a Middle Eastern spice combination that includes sumac, crushed sesame seeds and a thymelike regional herb from a woody bush.

You’ll accuse me of stretching a point, but I would include the Women’s Industrial Exchange in this roll call of ethnic eating in Baltimore. Founded in 1880 as a means of helping needy gentlewomen earn an income, it has been going strong ever since on the same corner of North Charles Street, selling handmade craft articles in the front room and handmade WASP food—plain, unadorned, old-fashioned, superbly ordinary American food—in the back room.

Outside Greenwich and Locust Valley, there aren’t many cheerleaders these days for WASP food, but if a few more serious eaters would try the industrial exchange (closed for renovation until late spring) maybe that would change. How’s this for lunch: a pile of the best chicken salad you’ve ever tasted, a block of ruby-red tomato aspic and a deviled egg, for a big $6.75? Add a cupcake—yes, a cupcake—or a wedge of lemon meringue pie for $3.

Mencken fans will have noticed a few things missing. The old grouch was a great drinker who called himself “omnibibulous” and described the dry martini as “the only American invention as perfect as a sonnet.” He was a great eater, who termed crab à la Creole “the most magnificent victual yet devised by mortal man.” But much of Mencken’s Baltimore is gone, despite the city’s predilection for the tried and true.

The hometown beer, National Bohemian, the beloved Natty Boh, is brewed in North Carolina now. Other icons of the Teutonic culinary culture have vanished as well, including many of Mencken’s favorite restaurants, like Miller Brothers, where my father took me as a lad to eat turtle soup; Schellhase’s, where Mencken’s Saturday Night Club met; and Haussner’s, which was stuffed with paintings and sculptures that brought more than $10 million at auction when it closed down. You can still find a snickerdoodle cookie, but sour beef and dumplings, Baltimore’s version of sauerbraten, is disappearing fast.

Depressing to report, Marconi’s, a deliciously anachronistic French-Italian salon on Saratoga Street, has lost much of its charm, thanks to an aesthetically criminal remodeling ordered by its new owner, Peter Angelos, a strong-willed millionaire who also owns the Orioles. The handsome Venetian wallpaper is no more, an ugly acoustic ceiling has been installed and the floor has been overcleaned.

But the thick broiled lamb chops with electric-green mint jelly (a favorite of Mencken’s and of my wife, Betsey) have survived, at least until now, as has the fudgy chocolate sundae so beloved by generations of well-bred Baltimoreans.

Bright new places have sprung up, of course. One of the first was Nancy Longo’s Pierpoint, still the place to go for modern versions of traditional Baltimore dishes and innovative uses of prime Eastern Shore produce. Gotta try her smoked crab cakes. Much more recently, the Red Maple, a long, skinny room designed by someone just back from the Milan Furniture Fair, has mesmerized the city’s noctambulist young. More a bar than a restaurant, it nevertheless serves classy Asian “tapas” like duck egg rolls and shrimp and tuna tartare.

But the undisputed prince and princess of Baltimore gastronomy at the moment are Tony Foreman and his wife, Cindy Wolf. A grape nut and a buddy of Robert Parker, the internationally influential critic, who lives not far from here, Mr. Foreman oversees the couple’s two restaurants, Charleston, downtown, and Petit Louis Bistro in semisuburban Roland Park. Neither is Baltimore-specific; Petit Louis features dishes like choucroute garnie and cassoulet, in Paris-level versions, and Charleston’s long menu owes as much to Maine, South Carolina and Louisiana as to Mary land.

“This is an in-between town,” Mr. Foreman said over a bottle or two of fine Châteauneuf-du-Pape. “Not Southern, not Northern. People have a Northern edge and a Southern graciousness. They care. If they dig it, they let you know; if they don’t, they let you know. That makes our job easier.”

Ms. Wolf’s crisp, light-as-air fried green tomatoes make a splendid foil for her crab and lobster hash. Her shrimp with grits, tasso and andouille takes you to New Orleans in an instant. Her lamb and pork and ultrafresh fish never disappoint. And the cheeses, a dozen or more every night, knowledgeably chosen and intelligently served, are enough to make any restaurateur proud.

Now why, you may be asking, especially if you grew up just after World War II, why has he written all this without a single word about Lady Baltimore cakes? Well, those delectably rich confections, whose layers are separated by fluffy, rosewater-scented white frosting studded with chopped raisins, orange peel, figs and pecans, have little or nothing to do with this city.

The name originated in Lady Baltimore, a 1906 novel by Owen Wister about a young man who walks into a tearoom in a Southern city, modeled on Charleston, S.C., to order a wedding cake. What he chooses is a Lady Baltimore cake, no doubt about that, but exactly why it is so named is unclear. Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, founded Mary land, but history records no link between his wife and baked goods. Neither of them ever visited North America.

My mother used to make Lady Baltimore cakes for family festivities, and they are favorites of mine. I have never come across one in a restaurant here, but Eddie’s of Roland Park, the city’s premier fancy grocery, makes a dandy one on special order.

—Baltimore, February 19, 2003

In Hoagieland, They Accept No Substitutes

When the future Edward VII, then the Prince of Wales, visited this staid old city in 1860, he had a little trouble getting his bearings. During his stay, he reported later, “I met a very large and interesting family named Scrapple, and I discovered a rather delicious native food that they call ‘biddle.’”

Almost a century and a half later, venerable families and idiosyncratic foods remain evocative parts of the Philadelphia scene, as familiar as the statue of William Penn atop City Hall and the exploits of Rocky on film. There are still oodles of Biddles around, and scrapple still adorns the breakfast menus of lowly diners and elegant hotels alike.

Some Philly Phoods remain resolutely local, like scrapple and water ice. Others, like cheesesteaks and hoagies, have spread across the country, though often in ersatz form. Here on their home turf, you and I can sample the genuine articles in their unpretentious, calorific, often sloppy splendor.

Italian-Americans from South Philadelphia and German-Americans who settled in and west of the city, misleadingly known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, have contributed the most to making Philadelphia a street-food showcase, a kind of Middle Atlantic Singapore.

But stop in some noontime at the 110-year-old Reading Terminal Market in Center City, where all the culinary streams flow together, or at Sarcone’s Deli or Jim’s Steaks, a few blocks to the south, and you will quickly realize that this food has won the hearts of Every-man and Everywoman—blacks and whites, locals and tourists, beefy working stiffs, primly dressed matrons, youngsters wearing the No. 3 of their hero, Allen Iverson of the 76’ers.

An astonishing number of old institutions survive. Bassetts ice cream, founded 1861, is the nation’s oldest brand and one of its best. Pat’s King of Steaks has been around since 1930. Esposito’s has been in the meat business since 1911 and Termini Brothers in the pastry business since 1921.

Sadly, though, pepper pot soup, one of the grand Philadelphia gastronomic traditions, appears to be all but defunct. Although George Washington’s chef at Valley Forge probably did not invent it, as myth maintains, it was for decades as integral a part of southeastern Pennsylvania life as Independence Hall and sculls on the Schuylkill.

Gone with the wind is the rousing cry of the street hawkers:

All hot!

All hot!

Pepper pot!

Pepper pot!

Makes backs strong.

Makes lives long.

All hot! Pepper pot!

Old Original Bookbinder’s closed last year, depriving not only those who devoured the spicy soup at its tables, but also those (like me) who used to buy the brew in cans. The City Tavern still serves pepper pot, but it is made with salt pork and salt beef, not with tripe, as specified by the noted Philadelphia cook Sarah Gibson Rorer in her classic cookbook of 1886. For the authentic version, pepper pot lovers must now repair to the Swann Cafe at the Four Seasons Hotel, where it is served intermittently, October through January.

Philadelphia’s greatest food export is the cheesesteak, which is built around beef sliced paper thin and sizzled very briefly on a griddle. Although not in the same food-as-fuel league as the hamburger, the hot dog and the pizza, it has made a national name for itself in the last quarter-century, and its hold on the city of its birth seems unshakable. Which raises an eschatological question: Why should pepper pot soup die out while the cheesesteak and its cousin, the hoagie, thrive?

“Philadelphia is subject to the same trends as the rest of the country,” said Elaine Tait, the longtime food editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, now retired. “We’ve stopped eating things like kidneys and liver and tripe. We’re a snack food nation now, and the cheesesteak and hoagie are perfect—quick, inexpensive meals on a bun.”

The Big Three of cheesesteaks, each championed with pugnacious intensity by a phalanx of ferocious partisans, are Jim’s, Geno’s and Pat’s. Risking damage to my digestive system, to say nothing of my clothing, I returned to all three of them recently, in pursuit of gastronomic truth and beauty.

Pat’s and Geno’s, a pair of squat, unadorned, utilitarian structures, stand diagonally across from each other at the southern end of the Italian Market, where Ninth Street, Wharton Street and Passyunk Avenue cross. Neither has indoor seating. Each has one service window for sandwiches and another for drinks and fries. Each is rimmed by plastic tables and benches firmly bolted to concrete sidewalks and shielded from sun, rain and snow by flat metal roofs that project from the main building. Each is open 24 hours a day.

This is the drill: You stand in line, inching toward the window. When you get there, you speak your piece to the stone-faced counterman quickly, unless you want trouble from those behind you. If you say, “Whiz, with,” as you should, your sandwich will come with grilled onions and Cheez Whiz, the unabashedly orange processed goo made by Kraft Foods; for this purpose, if few others, it is absolutely ideal. White American cheese and provolone are much less satisfactory options. “Without,” meaning “hold the onions,” sounds subversive to me.

Pat’s, the oldest of the Big Three, claims to have originated the cheesesteak. It uses torpedo-shaped rolls from Vilotti’s bakery; they are a bit firmer than the Amoroso bakery’s rolls favored by most other cheesesteak emporia. A good thing, too, because so much meat and other stuff is jammed in that a flabby roll might fall apart.

When you pick up your Coke or iced tea or whatever at the drinks window, look down. There, buried in the sidewalk beneath your feet, is a red stone bearing a surprisingly reverent inscription: “On this spot stood Sylvester Stallone filming the great motion picture Rocky, Nov. 21, 1976.”

Geno’s steaks are almost self-effacing. The cheese dissolves into a runny sauce; the strips of beef are laid precisely on the roll, rather than in a tangle; and the onions are sparsely applied. But one thing is boldface: the owner’s point of view. It’s on display: “Joe Vento says, ‘Let Us Never Forget 9/11 and Never, Never Forgive.’”

Jim’s is something else again. Much closer to Center City, in the midst of the South Street tourist district, it draws far more cheesesteak neophytes. Its black-and-white faux–Art Deco interior makes a stab at décor. It has indoor tables, chairs and even toilets. Its grill men chop the steak into small pieces with a few quick blows from the edges of their spatulas.

The resulting sandwich is a near-perfect amalgam of juicy, greasy bits of beef and bland, gummy cheese—maybe not Philly Mignon, as proclaimed on one Web site, but irresistible. Both raw and grilled onions are offered; a mixture gives the sandwich a welcome bite. Jim’s wins my blue ribbon, but then, what do I know? I’m not Italian and not from Philadelphia.

Cheesesteaks are only one of the lures of South Philadelphia, which is the heartland of the city’s Italian-American community. The Ninth Street Market, with shops and stalls flanking the street for a dozen blocks, is a delightful anachronism—the oldest working outdoor market in the nation.

Claudio’s cave of marvels, packed with olive oils, anchovies, tuna and balsamic vinegars, is entered through a curtain of hanging cheeses. Cannuli’s butcher shop, whose floor is covered with sawdust, has a gargantuan oven that can, and regularly does, cook 16 boned and stuffed pigs at once.

Settlers from Naples, Sicily, Calabria and Abruzzo poured into South Philadelphia in the 1880s and 1890s, and in the 1950s singers like Mario Lanza, Frankie Avalon, Fabian and Bobby Rydell sprang from these hard streets. But in the last quarter-century, more and more Italian-Americans have moved to the suburbs, notably those in New Jersey. Latin American and Asian immigrants have taken their place, and now Huong Lan, on Eighth Street, offers “Vietnamese hoagies,” whatever those might be, along with pho and bun bo Hue.

According to those who have explored the murky recesses of local food history, hoagies owe their name to the Hog Island shipyard on the Delaware River. During the Depression, or so the story goes, construction workers there used to buy Italian sandwiches from a luncheonette operated by one Al DePalma, who called them “hoggies.” Time changed the name to hoagies.

Hoagies are not fundamentally different from New York’s heroes or Boston’s grinders or Everytown’s submarines. Call them what you like, but Philadelphia must eat more per capita than anyplace else, and in a city where almost everybody, including Wawa convenience stores, fills eight-inch-long bread rolls with cold cuts, South Philadelphia fills them better than anyone.

The bread is the key to quality. So who better to make a great hoagie than a great bakery? That would be Sarcone’s, a fixture on Ninth Street, which a few years ago opened a tiny deli a few doors away. Its Old Fashioned Italian (Gourmet) hoagie is a minor masterpiece. A roll with a crunchy seeded crust and a soft, yet densely chewy, interior provides a solid base with plenty of absorptive power. Both are sorely needed after they pile on the prosciutto, coppa, spicy sopressata, provolone, oregano, tomatoes, onions, hot peppers, oil and vinegar.

A slug of Fernet-Branca (fittingly Italian) might help, too.

Ed Barranco, owner of the nearby Chef’s Market, which serves Society Hill’s carriage trade and catering clients across the city, pointed us toward Sarcone’s, and since we liked it so much, we decided to take him up on another recommendation. We would be well advised, he said, to try the chicken cutlet, sharp provolone and broccoli rabe sandwich down at Tony Luke’s.

“Good?” I asked him. “Good?” he replied, eyes shining. “Nah, it’s more than good. It’s Italian.”

So we found the joint, tucked under an I-95 overpass, in south South Philadelphia. We ordered roast pork instead of chicken—I have a thing for Italian-style roast pork—and ate it in the company of weight lifters and truck drivers, several of whom left their rigs idling at the curb.

A canny combo it was, too: bitter, garlicky greens; pungent, smoky cheese; and tender, mild, juicy pork.

After heavy lifting like that, especially on a warm day, what you need is a Philadelphia-style Italian water ice, served in a little paper cup with a plastic spoon. It is less grainy than granita, more so than sorbet. It dissolves as you eat it, so you get food and drink at once. Most of what is sold these days is nothing but sugar, sugar, sugar, but at its best, water ice has the unmistakable tang of fresh fruit, intensified.

John’s is the classic spot, a tiny stand that serves only four flavors—cherry, pineapple and lemon (all made from fresh whole fruit, not syrup), plus chocolate. The cherry tastes the way cherries taste in northern Michigan in high summer. In keeping with the times, Pop’s, which started as a cart pushed by Filippo (Pop) Italiano in 1932, offers 15 flavors on most days.

My wife, Betsey, ordered lemon, and I ordered mango, both marvelous. But neither of us tore into ours with quite the exuberance of Rocky, a three-year-old in from Jersey with his mother for a day’s grocery shopping in her old neighborhood. Rocky opted for root beer.

German-American food entered the Philadelphia mainstream long before the first Italians arrived here. Scrapple and pretzels have survived.

I have never quite understood the squeamishness that scrapple excites in a lot of people. True, the ingredients sound slightly revolting—“pork stock, pork, pork livers, pork skins, pork hearts, pork tongue,” to quote part of one label. But sausage generates no such qualms, unless you consider the old admonition against watching the unappetizing manufacturing process.

No matter. Pennsylvanians, former Pennsylvanians and inhabitants of adjacent states like Delaware and New Jersey have eaten scrapple for centuries with no harmful effects. Philadelphia lawyers eat it. Benjamin Franklin supposedly ate it.

As the name implies, it is made from the scraps of pork left over after most of the pig has been turned into ham, bacon, pork roasts and pork chops. These scraps are cooked with spices (usually sage and pepper), cornmeal and sometimes buckwheat or whole wheat flour. The resulting loaf is cooled and cut into half-inch slices, which are fried in butter or shortening until they turn a crisp, ruddy brown on the outside. The inside remains soft and luscious.

Growing up in a Pennsylvania Dutch family in Ohio, I learned to eat scrapple with maple syrup, which made it seem to me like a combination of pancakes and sausage. In Philadelphia, it is sometimes served with ketchup, and in the Dutch country, where it is often still called panhaas, I have seen it topped with dark molasses.

Made by a company dating from 1895, Hatfield scrapple, more peppery and less intensely sage-flavored than some, is served at the luxurious Ritten house Hotel. The Silk City Diner features another local favorite, Habbersett, alongside huevos rancheros, bagels and grits, cooking it to an unusually golden hue. The inside is as creamy as an oyster.

But nothing topped the scrapple we were served at the nonpareil Down Home Diner in Reading Terminal, a bastion of Pennsylvania Dutch quality. The diner belongs to Jack McDavid, who comes from rural Virginia and is known for ferreting out prime ingredients. His scrapple is made by a small company called Godshall’s, based in Tel-ford, Pa. Pale, salty, moist and buttery, it appears to contain more spice, more meat and less filler, giving the end product an unusually rich texture.

Like scrapple, pretzels originated in Germany, where they are called “Brezels.” This part of Pennsylvania produces tons of standard, hard-baked pretzels, but it also produces something special—soft pretzels, made of nothing more than flour, yeast (to make them rise), water, a little salt and a smidgen of brown sugar.

At the Fisher family’s stand, the dough is mixed in an ancient Hobart machine. The pretzel bender, an elderly Amish lady in a gauzy white bonnet, rolls it out with her hands to the diameter of a little finger, then twists it into shape in one practiced motion. After baking, the pretzels are sprinkled with coarse salt and sold while still hot. A coat of melted butter is optional; a filigree of brown mustard is absolutely required. Without mustard, you’ll look like an auslander.

The pretzels are incomparable—light, airy and tasty. Their leaden street-corner competition can’t cut it, any more than an airline bagel can match one of Murray’s.

Well, then. Scrapple for breakfast, a couple of pretzels for lunch. What’s for dessert? The market has an answer for that, too, in the form of Bassetts ice cream. The company that makes it, established 140 years ago by a Quaker schoolteacher, is run today by his great-great-grandson. At its marble counter, you can order a cup, a cone or several pints, packed in dry ice for travel if need be.

Excavated from the tubs with an old-fashioned spade rather than a scoop, this is small-town, butterfat-laden, raid-the-fridge-at-midnight ice cream. A spoonful is as satisfying as a gallon. Of the 40-odd flavors, vanilla is the favorite (no surprise), but there are also hard-to-find, old-time treats like butter pecan, banana, rum raisin, peach and nut-laden pistachio.

Why not try two scoops, say double chocolate and cinnamon?

—Philadelphia, May 28, 2003

Bagging the Endangered Sandwich

When I first came to New York, at 17, I pestered the school friend I was visiting until he took me to Lindy’s for corned beef and cheesecake. I figured that that was the closest an Ohio kid was likely to get to the fragrant, seductively shady world of Damon Runyon and Walter Winchell—“boxers, bookmakers, actors, agents, ticket brokers, radio guys, song writers, orchestra leaders, newspapermen and cops,” as Runyon described them, “still sleep-groggy” as they gathered for breakfast at 1 p.m., “but shaved and talcumed and lacking only their java to make them ready for the day.”

Lindy’s has long since vanished from Broadway, along with Leo Lindemann, its creator, and Sky Masterson, Nathan Detroit and the other urban wayfarers in Runyon’s cast of semimythic characters. Gone, too, are Phil Gluckstern’s and Arnold Reuben’s and Lou G. Siegel’s, where serious fressers (overeaters) could count on finding corned beef with taam, the indispensable Jewish taste. They’re all part of the Oh-So-Long-Ago, as Winchell called it, like Jack Dempsey and Jack Benny.

Now, newcomers to New York—not 17-year-olds, I guess, but 21-and 22-year-olds—angle for tables at Balthazar or Nobu. Pals initiate them to Krug instead of cream soda.

Corned beef is alive and well, of course. It shows up around the world, in one guise or another. But in New York, where once it was king, good kosher-style corned beef is as rare as nightingales’ tongues.

You find plenty of corned beef in Dublin, as the centerpiece of corned beef and cabbage, the reliably nourishing standby of the frugal house wife, and in Boston, as an essential component of a New England boiled dinner. You find it in corned beef hash, which has been a staple on American restaurant and club menus for decades.

My stepdaughter, Catherine Brown, found it in a jungle clearing on an Indonesian island—Brazilian corned beef, straight from a can with a cow on the label, heated over a kerosene stove, served with sweet potatoes.

All the other varieties, to tell the truth, pale in comparison with the moist, garlicky stuff Jewish immigrants brought with them to New York from central and eastern Europe. Yet, today you can spend yourself halfway to the poor house and give yourself heartburn (not to mention heartache) looking for the kind of corned beef sandwich that defined eating in Manhattan the way onion soup defined eating in Paris: steamed, thinly sliced meat stacked high on rye bread, slathered with spicy mustard, a half-sour pickle on the side.

Woody Allen gave Manhattan corned beef one last (or next-to-last) hurrah in Broadway Danny Rose, his 1984 film about a small-time Broadway agent, which included scenes shot in the Carnegie Delicatessen. But Jerry Seinfeld and his buddies, the quintessential pop-culture New Yorkers of the 1990s, hung out not in a deli but in a diner or outside a gussied-up soup kitchen.

Except for the Carnegie and the Stage, today’s Broadway is mostly a glorified food court, packed with franchised joints of every description, serving hamburgers and bagels and pizzas and the like, many of them owned by a family of real estate operators, Murray, Dennis and Irving Riese.

There is also a Riese-owned restaurant called Lindy’s on Broadway between 44th and 45th Streets, but any resemblance to the original is purely coincidental. The only authentically New York aspect of the place is the surliness of the service.

So where do you find the good stuff? Apprehensive about possible doubts—make that probable doubts—concerning the corned beef credentials of a man of Midwestern Lutheran origins, even if said Midwestern Lutheran has been dribbling deli mustard down his ever-expanding front for many decades, I sought the help of Tim Zagat, the guidebook publisher. A New Yorker in both palate and pedigree, he claims to have eaten corned beef regularly since puberty, including once a week at his Riverdale prep school.

Mr. Zagat’s 1999 guide to New York restaurants reflects the declining role of the delicatessen, and hence corned beef, in New York gastronomy. Not one of the 50 establishments top-rated for food is a deli, although two are pizza parlors and one is a soup kitchen. Zagat’s amateur critics ate in delis a lot (the Carnegie was the seventh-most-visited spot in the survey), but they must have suffered.

Throwing caution to the wind, Mr. Zagat and I decided to taste for ourselves. As a concession to age—neither of us is young anymore—we asked the countermen to give us thinner sandwiches than usual. Though obviously offended, they complied.

The sign outside the Stage Delicatessen (834 Seventh Avenue, between 53rd and 54th Streets), meant to take a poke at the Carnegie, betrays a certain defensiveness. “Why wait on line,” it asks, “when you could be eating now?” In the heyday of Max Asnas, the founder, the Stage bragged about the quality of its food, not how quickly it could find you a table.

But the place still smells right (a little greasy, a little garlicky), waiters and customers still abuse each other in a good-natured way and the sandwiches are still named for celebrities (though it’s a stretch to think of Fran Drescher and Richard Simmons, both creatures of television, as Broadway types). It still deals gently with Iowans who don’t know which is the bagel and which the lox.

As for the corned beef, it’s a comedown from the 1960s, when the Stage was listed in a book called Great Restaurants of America. The meat is too dry, too pink, too wan in flavor. If there is really a “secret recipe,” as claimed, they must have forgotten to let the cook in on the secret.

Another big disappointment came at Katz’s (205 East Houston Street at Ludlow Street), a 112-year-old institution that figured in When Harry Met Sally. There’s nothing not to like about the terrazzo-and-Formica ambiance, with a cafeteria counter along one side and signs instructing you, as of yore, to “Send a Salami to Your Boy in the Army.” You have to love the fact that they still use meal tickets (does anyone else?) and cut the corned beef by hand, with venerable knives sharpened down almost to nothing.

Katz’s hot dogs, crisped on the grill, and its garlic-laden knoblewurst are both vaut le voyage downtown. But the corned beef sandwich is only O.K.—moist meat with a rough texture, but with a slightly musty flavor instead of the bright, pungent taste that you look for. The bread is rather bland, as well—a lot like supermarket rye, though I wince to say so.

The Second Avenue Deli (156 Second Avenue, at 10th Street) has the least authentic interior—a recent redesign by Adam Tihany, no less—but the most authentic everything else. This was the domain of Abe Lebewohl, a true Manhattan treasure, part social worker, part delicatessen genius, who was gunned down in 1995 by an unknown villain who remains at large.

Here everything is kosher; even the cheesecake is made with tofu, to avoid transgressing the boundary between meat and dairy. Many other delis serve “kosher-style” food, which means that it looks and (they say) tastes the same, but is not prepared in strict compliance with Jewish dietary laws.

And here the corned beef, prepared in the basement, is the genuine article. “Juicier, richer, more zaftig,” as my grease-spotted notes say. “A real knockout.” Real kosher corned beef isn’t unobtainable after all.

I think the question always asked by Abe Lebewohl’s brother Jack or one of the other servers has something to do with it. “Lean or juicy?” they ask, before anyone has a chance to say “extra lean.” Confronted with that choice, most people opt for juicy, which means they get enough fat, Jack Lebewohl says, to boost the flavor and make sure the sandwich doesn’t get dry.

Another thing: People from Sweden walk in, sure, as three did just a few days before our recent visit, but this is still primarily a neighborhood spot. Some customers come in six or seven times a week, and on Friday, the locals pack the place. They know their corned beef; they make sure that Jack keeps things up to snuff.

The Carnegie (854 Seventh Avenue at 55th Street) is only a half-step behind, if that, despite the agonizingly corny names it gives to some of its sandwiches (e.g., “The Mouth That Roared,” which is roast beef and Bermuda onion). And despite a less demanding clientele (big groups from Kansas City and Utah, on my last visit, but some from the Bronx, too). Sometimes the country boys exhibit unacceptable table manners; when he was running for the vice presidency, former Senator Lloyd M. Bentsen of Texas tried in vain to eat his bulging sandwich with a knife and fork.

Every week, the Carnegie corns 15,000 pounds of beef at a plant in Carlstadt, N.J., starting with well-marbled 8-to 12-pound briskets cut from the breast of the steer. Injected first with a saline-and-garlic solution enriched with allspice, thyme and mustard and coriander seed, the beef is then pickled for about a week in barrels filled with the same solution.

Some is sold to other restaurants, but about 10,000 pounds a week are cooked as needed in the Carnegie’s damp, dungeonlike basement. The meat is boiled for two to two and a half hours in 35-gallon pots, then carried upstairs, where it is steamed and sliced to order, across the grain, of course, on razor-sharp rotary cutting machines. The blades are replaced once a month; the machines themselves, exhausted by constant use, are sent back for rebuilding every three months, said Sanford Levine, one of the Carnegie’s co-owners.

Sandwiches are built on thin, seeded rye bread delivered four times a day from the Certified Bakery in Union City, N.J. More than a dozen ultrathin slices of beef go into the average sandwich, a few lean, a few fat. That’s the way Leo Steiner, who first put the Carnegie on the map, liked it best.

“It should melt in your mouth,” he confided to a reporter almost a decade ago. “I don’t like to chew. Thinner, the flavor comes through.”

Broadway and environs still have plenty of delicatessens, of a sort. There’s the All-American Gourmet Deli, the Celebrity Deli, Roxy’s (named after a defunct theater), the Crown Deli (“Featuring Colombo Yogurt”) and the 55th Street Deli, a produce stand-cum-convenience-food shop. Downtown, I spotted delis touting waffles or salad bars. These are the kinds of places that would happily sell a passing innocent a corned beef and Swiss on toasted seven-grain.

It goes without saying that none of them, or their yuppified counterparts elsewhere, are authentic, thumb-in-your-soup, garlic-scented, damn-the-cholesterol delis. That kind of place has mostly vanished from midtown and the Lower East Side as the Broadway crowd has thinned and the Jewish population has scattered to New Jersey and Queens and Long Island, losing touch with its roots in the process.

We’re talking heavy social anthropology here, but we’re also talking gastronomy.

“When we were all on the Lower East Side, every mom-and-pop store cured its own,” said Rabbi Arthur Herzberg, a professor of humanities at New York University and a kosher food maven of considerable standing. “That was one thing. Now you get two-week-old corned beef, supermarket corned beef and corned beef and cheese—utter desecrations of Jewish soul food.”

The genuine article is even harder to find elsewhere in the country. Some film people swear by Nate ’n Al’s in Los Angeles, but in my experience, kosher corned beef starts to fade once it wanders beyond commuting range of Manhattan. (Zingerman’s in Ann Arbor, Mich., is an honorable exception.)

Branches of New York nosheries have failed in Beverly Hills, New Jersey, Boston and the Washington suburbs in recent years, and several decades before that, my friend Stanley Karnow, the Brooklyn-born journalist and historian, lost his shirt, or at least a sleeve or two, struggling to teach the long-suffering Hong Kong Chinese the finer points of Jewish gastronomy.

Without a maven or two a day among its customers, any deli will sooner or later lose the touch, exactly like a Thai restaurant in Afghanistan. And without real delis, there can be no real New York corned beef—rich and warm and tender, slightly salty but also slightly sweet, with just enough fat clinging to the meat to keep it moist. Ordering the stuff extra lean, the way some people do, is about as pointless as drinking 3.2 beer.

—New York City, September 15, 1999

Correction: September 21, 1999, Tuesday

An article last Wednesday about a search for a good corned beef sandwich in New York City misidentified the delicatessen that has a sign saying “Why wait on line when you could be eating now?” It is the Ben Ash Delicatessen, on Seventh Avenue and 54th Street, not the nearby Stage Delicatessen.

Enduringly Yankee, with a Modern Twist

Not so long ago, lobsters and baked beans pretty well defined the parameters of Maine gastronomy—at least for “folk from away,” as outsiders are called in the local lingo. The old reliables are still there: a traveler heading north along the coast from Kittery soon starts seeing signs advertising lobster pounds, and the B&M baked bean plant, a sentinel of Down East tradition, stands along Interstate 295 near downtown Portland.

But times have changed. In the last decade or so, Maine fishermen have begun harvesting a broader range of marine delicacies. Maine farmers have begun raising traditional breeds of pigs and sheep by old-fashioned methods. Despite a cranky climate, Maine market gardeners have found new ways to coax remarkably toothsome vegetables from the state’s thin, rocky soil.

As the raw materials have improved, so have the restaurants. Home-grown chefs and newcomers from all over the country have evolved cooking styles with a strong sense of place, the beginnings of a regional, seasonal Maine haute cuisine. At the moment, says Corby Kummer, who reviews restaurants for Boston magazine, “Maine is where you find the food action in New England.”

On a trip that my wife, Betsey, and I made late this spring, in impossibly beautiful weather, with blue sea and bluer sky vying for attention, four places stood out from the crowd. John Thorne was no doubt right when he said in his fine newsletter, Simple Cooking, that “the Maine temperament is enduringly Yankee in its sneaking delight in the mortification of the flesh for the good of the spirit.” But for us, at least, there was only pure pleasure that week.

Clark Frasier, a Californian, and Mark Gaier, who grew up in Piqua, a small town in western Ohio, met in the kitchen of Stars, Jeremiah Tower’s groundbreaking brasserie in San Francisco. They have turned an old post-and-beam farm house on a back road near Ogunquit into Arrows, an urbane restaurant surrounded by sumptuous flower and vegetable gardens, where they combine Maine-raised belon oysters, Maine scallops and Maine venison, among many other local products, with French, Italian and Chinese preparation techniques.

A Mainer through and through, Sam Hayward runs Fore Street, a perpetually packed restaurant near the Portland docks. Cooked without fuss in a wood-fired oven and on rotating spits in an open kitchen, unobtrusively served in an old ware house, the food speaks in the laconic accent of his state. “Pork Loin,” the menu announces. “Hanger Steak. Marinated Maine farm rabbit.” There is an integrity to the man and his work as rock-ribbed as the Maine coast.

Farther north in Rockland, Melissa Kelly, a New Yorker who won plaudits by the bushel at the Old Chatham Sheepherding Company Inn in the Hudson Valley, is rapidly building a new following with Primo. In a Victorian farm house with kitchen gardens (and a couple of Gloucestershire Old Spot pigs) out back, she gives freer rein to lessons learned from her Italian-American mother than she did at Old Chatham, adding pancetta to a creamy pea and fiddlehead fern soup, and serving seared black sea bass on a bed of fennel and Sardinian couscous.

Tom Gutow, who comes from Walloon Lake, Mich., is not as well known yet as the others. The Castine Inn, which he has run since 1997, is tucked away on a peninsula that leads down toward the fishing port of Stonington, well off the tourist track. But Castine may be Maine’s best-kept white-clapboard village (Mary McCarthy and Robert Lowell both had houses here), and Mr. Gutow shops and cooks with an unbridled passion. When he really gets going, he uses ingredients from as many as 30 regional producers in a single evening’s dishes.

The single best thing we have eaten this year resulted from Mr. Gutow’s skills as a produce scout and Mr. Hayward’s steadfast refusal to paint any lily. When Mr. Gutow took us to meet Eliot Coleman and Barbara Damrosch at their remarkable Four Seasons Farm, one of his main suppliers, they gave us several small bags full of freshly pulled or picked vegetables, including some golf-ball-size baby turnips. We had reservations that night at Fore Street, so we took the turnips along and asked Mr. Hayward to cook them for us.

He steamed them, added salt, a knob of butter and a shower of chervil, and served them as a separate course so that they might shine on their own. Shine they did. We had found the Platonic ideal of turnips. That typical metallic sourness was there, but the cold Maine winter had intensified their sugars, adding a burst of sweetness.

They reminded me of one of my favorite dishes of the 1970s, the roast duck with turnips that André Allard served in his Left Bank bistro for a few weeks each spring. Only then, he explained, were the turnips right. Now I understand what he meant.

Before taking a closer look at the pioneers of the new Maine cuisine, let us take a fond glance at those who keep faithfully to the old ways.

I have been stopping for years at Bob’s Clam Hut on Route 1, founded in 1956, around which Kittery’s complex of outlet malls has since grown up. Bob’s hasn’t changed; it remains for me a kind of roadside seaside Nirvana. They convert hard-shell Quahog clams into buttery, blessedly unthickened chowder, and they fry soft-shell Ipswich clam bellies to golden crunchy perfection. These people are demons at the Frialator, changing the oil several times a day to ensure freshness. Their onion rings and lemonade are good, too. Stop in on your way to Bar Harbor or some more proletarian retreat this summer.

Route 1 is littered with diners and cafes. Moody’s Diner in Waldoboro is the genuine old-fashioned article. John Thorne recommends the fried tripe with onions, a reminder that this remains a hardscrabble state, but we took the suggestion of Holly Billings, our cheery young waitress, and ordered four-berry pie. A slice of bliss appeared, still hot from the oven, juices of raspberries, strawberries, blackberries and blueberries oozing through tender (lard-based?) crust.

The Thomaston Café is a hybrid, embracing the traditional (haddock fishcakes and fluffy baking-powder pancakes), the innovative (wild mushroom hash) and the eclectic (cheese blintzes with blueberry sauce and black bean burritos). The filling in the divine coconut cream pie is creamy, not gluey, and the graham cracker crust is crunchy, not soggy. The names of suppliers are listed on the menu. Clearly a chef, no mere cook, is at work here; he is Herbert Peters, German-born, with 30 years in the trade.

With typical Yankee frugality, he charges extra for real Maine maple syrup.

No occasional visitor should dare to say who serves Maine’s best lobster roll, that magical concoction of lobster and mayonnaise served on a toasted bun, unique to New England, which resembles two slices of bread hinged together. But my childhood friend Ethel Stansfield, a longtime resident of Wiscasset, says the best she has eaten are at Red’s Eats, an idiosyncratic kiosk at the foot of the village’s main street. Others agree. Red’s is so small that it’s portable; it was trucked over from Boothbay Harbor several decades back.

Waterman’s Beach Lobster, just south of Rockland near Spruce Head, won a James Beard award last year. It is the quintessential Maine lobster shack, consisting of a small gray house, a deck with picnic tables, partly covered with an awning, and a jetty with traps and buoys stacked at the far end.

That’s it, and that’s enough. Sandy Manahan and Lorri Cousens, the sisters-in-law who run it, open only Thursday through Sunday, devoting the other three days to their children. Their menfolk catch the shellfish and deliver them daily; the women steam them in big pots. “Never, ever boil them, an inch of water, no more,” Ms. Manahan told me. The result is sensationally sweet, supremely tender lobster, distinguished by its fine-grained texture.

A pair of one-pounders, with chips, coleslaw and soft drinks, cost us $28. The bay view toward fir-clad islets, a John Marin panorama in three dimensions, was free.

Both vegetable and flower gardens play parts in the allure of Arrows. An arbor covered with wisteria leads to the front door, and the main dining room, furnished in understated Craftsman style, looks out over trees outlined in tiny white lights, à la Tivoli, with pools of colorful blossoms beneath.

Thanks to cold frames and a green house, the vegetable plots were already bursting with life in May: so much arugula, frisée, butter lettuce, red romaine, oak leaf and radicchio that Mr. Gaier said he couldn’t use it all. Although it wasn’t on the menu, we asked for a mixed salad. What arrived was fresh proof of the primacy of ingredients; it was subtle, sweet, crisp as spring, with each leaf sounding a distinctive note.

The kitchen whiffed once or twice, but it hit a half-dozen home runs, including delicious house-cured prosciutto, smoky sweetbreads, planked Atlantic salmon with ginger and an artful plate of contrasting tastes and textures: roasted scallops served with Burmese rice cakes and a tart Vietnamese salad with mint, basil and peppers. When Arrows opened in 1988, Mr. Frasier said, “supplies were scarce, and there was no really good seafood to be had, believe it or not.” That problem has clearly been solved.

If Arrows has big-city aspirations (and big-city prices, with main courses about $40), Fore Street has a smaller-town feel (and smaller-town prices, with the most costly main dish at $26). It is Portland’s crossroads, patronized by young and old, rich and not so rich, with a bustling bar and a glassed-in larder full of handsome produce like the tender aromatic young mizuna from New Leaf Farm in Durham that Mr. Hayward pairs to masterly effect with Jonah crabmeat and avocado.

This is unashamedly bold-tasting food. Mussels are cooked with garlic-almond butter, the almond bits adding both crunch and sweetness. The rabbit, a good-size beast, comes with strips of applewood-smoked bacon from a Vermont butcher. Wild mushrooms, some of them gathered by the restaurant’s forager, Rick Tibbets, are roasted in the wood oven. I had deliciously meaty New Hampshire oyster mushrooms touched with veal broth; other seasons bring morels, chanterelles and pheasantbacks.

Fore Street’s bracing stew of mussels, tuna, sablefish and salmon, flavored with fennel, tomatoes and more of that applewood bacon, is another product of the wood oven. Desserts are just as plain-spoken; as a lifelong foe of slimy rhubarb, I was thrilled by Mr. Hayward’s chewy rhubarb crisp with a scoop of goat cheese ice cream.

You can eat plain or fancy at Ms. Kelly’s Primo. The wood-fired pizza (including a white pie with Vidalia onions, roasted garlic and wilted arugula) is hard to resist. So don’t. Order one to nibble while you decide whether to have “lobster pulled from its shell and served in a buttery nage of peas with their shoots,” maybe, or Winterpoint oysters from the Damariscotta River estuary, deeply cupped, with a mineral finish and roasted with ramp butter.

Some of the fish swam in distant seas (Copper River salmon from Alaska, daurade from France), but Ms. Kelly is also a dab hand with lobster. In season she does an aristocratic lobster and asparagus salad with curry oil. But we made do, and then some, with humbler dishes: a crackling fritto misto of whitebait, Meyer lemon and baby artichokes with sorrel aioli; juicy rosemary-grilled lamb chops with gnocchi, peas and mint; and a bowl full of warm, utterly irresistible zeppole (round doughnuts) tossed in cinnamon and sugar.

We might have been in Sorrento.

Mr. Gutow’s time in France with Michel Guérard and others shows in the delicacy and ambition of his cooking. A tiny starter of Penobscot Bay crabmeat with lavender mayonnaise and cardamom curry oil would have pleased the master with the way in which the flavors complemented rather than warred with one another. Steamed cherrystone clams with rice wine vinegar and sweet cicely, a seldom-used herb related to chervil, had an agreeably smoky taste.

A scallop from Blue Hill Bay, across the peninsula from Castine, rode to our table on a little raft of grilled leeks floating in a vividly, almost luridly, green chive broth. Sophisticated, labor intensive, not at all what one expects to find in a rural inn, it was flawlessly executed. So were minuscule rib chops from a just-weaned Cole Farm piglet. In the best French tradition, Mr. Gutow served a quartet of choice New England cheeses, notably York Hill Capriano, a goat cheese somewhat reminiscent of Parmigiano-Reggiano, which is also served at Craft in New York. It came with zinfandel honey.

The service, alas, was in the Fawlty Towers tradition. We waited 30 minutes for our starters and had to ask twice for bread. This is part of the risk in running a restaurant in so remote a spot. But Mr. Gutow and his wife, Amy, will eventually fix that, and meantime there are compensations like the gentle mural of the village that circles the dining room and the gorgeously orange-yolked eggs served at breakfast.

That, and the good Maine air. The longer I was in Castine, the more I thought of E. B. White, the New Yorker stalwart, who owned a saltwater farm in North Brooklin, not far from Castine. The breezes there, he once wrote, bear the “smell that takes man back to the very beginning of time, linking him to all that has gone before.”

Maine’s best-known purveyors of food ship fish and other fishy things. Rod Mitchell of Browne Trading Company in Portland sells not only cod from Casco Bay, haddock from the Gulf of Maine and sea urchins from inshore Maine waters, but also elvers from Spain and caviar from the Caspian Sea. Eric Ripert of Le Bernardin and Daniel Boulud of Daniel are customers.

One of his competitors is the improbable Ingrid Benis, who teaches American literature to Russian students in St. Petersburg in winter and prowls the docks of Stonington in summer, buying the best scallops, lobsters and peekytoe crab that she can find in these nutrient-rich waters. She ships them to 20 restaurants across the country, including Thomas Keller’s French Laundry in the Napa Valley and Charlie Trotter’s in Chicago.

Richard A. Penfold of Stonington Sea Products, an Englishman who learned his craft in the Shetland Islands, produces a superbly balanced smoked salmon in the Scottish style, neither as bland as the Norwegian product favored by the French nor as pungent as the typical Nova Scotia side, and a rich, glossy smoked haddock, known to the Scots as finnan haddie. (Cooked and flaked, it is the vital ingredient in a satisfying British breakfast and supper dish, the Arnold Bennett omelette.)

Mr. Penfold, who is 40, said he used both cherry and hickory wood in his ultramodern smoking plant, which opened in 2000. Although praised by critics and served by discriminating restaurateurs like Mr. Gutow, Stonington’s products are only now starting to reach the general market.

Great Eastern Mussel Farms, based in Tenants Harbor, is the largest mussel processor in the country. On a blustery May afternoon, I pounded across Casco Bay in a flat-bottomed boat with Tollef Olson toward one of his rafts, anchored near Clapboard Island, off Portland. He grows mussels on ropes hanging from four rafts, selling the production of two of the rafts to Great Eastern and marketing the output of the others himself. Each of the rafts, which are 40-by-40 feet, yields 60,000 pounds a year, provided that predatory eider ducks can be kept at bay.

Farmed mussels grow faster than wild ones, explained Mr. Olson, a onetime diver. Domestic consumption has doubled from 40 million to 80 million pounds in five years, in part, I feel sure, because techniques have been developed to trim off the bivalves’ wiry beards and get rid of the grit in their shells.

Big things are afoot ashore, too. Kelmscott Farm near Lincolnville, named after the English village where William Morris lived, and financed by Robert M. Metcalfe, one of the inventors of the Ethernet, breeds rare varieties like Cotswold sheep. It provided Ms. Kelly’s Gloucestershire Old Spots.

But Maine affords nothing quite as special to the gastronomically minded tourist as Four Seasons Farm on Cape Rosier, south of Castine. Mr. Coleman and Ms. Damrosch, who are as fit and burnished by sun and wind as the things they grow, have found ways to raise vegetables all winter, beneath unheated polyester hoop houses. “Outside, the climate is Maine,” Mr. Coleman said. “Inside, it’s New Jersey. And under the covers over the seedlings, it’s Georgia.”

The fruit of these new techniques is sold to markets and restaurants close to Castine. But the farm’s doctrines have spread across the land, through a television series and appearances at organic farming conferences. When Odessa Piper, the chef at the celebrated L’Etoile in Madison, Wis., had to cook at a New York gala before the growing season had begun in the upper Midwest, Mr. Coleman and Ms. Damrosch came through with vegetables—mâche, carrots, red-veined chard—whose vibrant flavors matched their good looks.

—Castine, Maine, July 10, 2002

FAR FLUNG AND WELL FED Copyright © 2009 by R. W. Apple Jr.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Glorious Summer of the Soft-Shell Crab

The sun was a blood-orange disk pinned to the horizon as Thomas Lee Walton eased his 24-foot Carolina Skiff into the creek and headed toward the Rappahannock River. An osprey was perched in a dead tree on the far shore. It was 6:05 a.m. We were going crabbing.

Our quarry was the Atlantic blue crab—Callinectes sapidus to marine biologists, which means “savory beautiful swimmer” in Latin. But not the run-of-the-mill fellows you boil up with plenty of Old Bay seasoning, then crack with a hammer before pulling out the sweet, delicate white meat. Mr. Walton fishes for “busters” or “peelers,” which are crabs that have already begun to shed their shells, or are about to, before growing new ones.

“Watching them shed,” Mr. Walton said with a tender reverence suprising in a rugged outdoorsman, “it’s like they’re reborn.”

If you catch them at the right moment and pull them from the water, the process of growth stops and you have a soft-shell crab, one of summer’s most prized treats, not only here on the rim of the Chesapeake Bay, but also, increasingly, in cities across the United States.