What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

CHAPTER ONE

Lochan

I gaze at the small, crisp, burned-out black husks scattered across the chipped white paint of the windowsills. It is hard to believe that they were ever alive. I wonder what it would be like to be shut up in this airless glass box, slowly baked for two long months by the relentless sun, able to see the outdoors—the wind shaking the green trees right there in front of you—hurling yourself again and again at the invisible wall that seals you off from everything that is real and alive and necessary, until eventually you succumb: scorched, exhausted, overwhelmed by the impossibility of the task. At what point does a fly give up trying to escape through a closed window—do its survival instincts keep it going until it is physically capable of no more, or does it eventually learn after one crash too many that there is no way out? At what point do you decide that enough is enough?

I turn my eyes away from the tiny carcasses and try to focus on the mass of quadratic equations on the board. A thin film of sweat coats my skin, trapping wisps of hair against my forehead, clinging to my school shirt. The sun has been pouring through the industrial-size windows all afternoon and I am foolishly sitting in full glare, half blinded by the powerful rays. The ridge of the plastic chair digs painfully into my back as I sit semi-reclined, one leg stretched out, heel propped up against the low radiator along the wall. My shirt cuffs hang loose around my wrists, stained with ink and grime. The empty page stares up at me, painfully white, as I work out equations in lethargic, barely legible handwriting. The pen slips and slides in my clammy fingers. I peel my tongue off my palate and try to swallow; I can’t. I have been sitting like this for the best part of an hour, but I know that trying to find a more comfortable position is useless. I linger over the sums, tilting the nib of my pen so that it catches on the paper and makes a faint scratching sound—if I finish too soon, I will have nothing to do but look at dead flies again. My head hurts. The air stands heavy, pregnant with the perspiration of thirty-two teenagers crammed into an overheated classroom. There is a weight on my chest that makes it difficult to breathe. It is far more than this arid room, this stale air. The weight descended on Tuesday, the moment I stepped through the school gates, back to face another school year. The week has not yet ended and already I feel as if I have been here for all eternity. Between these school walls, time flows like cement. Nothing has changed. The people are still the same: vacuous faces, contemptuous smiles. My eyes slide past theirs as I enter the classrooms and they gaze past me, through me. I am here but not here. The teachers tick me off in the register but no one sees me, for I have long perfected the art of being invisible.

There is a new English teacher—Miss Azley. Some bright young thing from Down Under: huge frizzy hair held back by a rainbow-colored head scarf, tanned skin, and massive gold hoops in her ears. She looks alarmingly out of place in a school full of tired middle-aged teachers, faces etched with lines of bitterness and disappointment. No doubt once, like this plump, chirpy Aussie, they entered the profession full of hope and vigor, determined to make a difference, to heed Gandhi and be the change they wanted to see in the world. Now, after decades of policies, intraschool red tape, and crowd control, most have given up and are awaiting early retirement, custard creams and tea in the staff room the highlight of their day. But the new teacher hasn’t had the benefit of time. In fact, she doesn’t look much older than some of the pupils in the room. A bunch of guys erupt into a cacophony of wolf whistles until she swings round to face them, disdainfully staring them down so that they start to look uncomfortable and glance away. Nonetheless, a stampede ensues when she commands everyone to arrange the desks in a semicircle, and with all the jostling, play fighting, desk slamming, and chair sliding, she is lucky nobody gets injured. Despite the mayhem, Miss Azley appears unperturbed—when everyone finally settles down, she gazes around the scraggly circle and beams.

“That’s better. Now I can see you all properly and you can all see me. I’ll expect you to have the classroom set up before I arrive in the future, and don’t forget that all the desks need to be returned to their places at the end of the lesson. Anyone caught leaving before having done his or her bit will take sole responsibility for the furniture arrangements for a week. Do I make myself clear?” Her voice is firm but there appears to be no malice. Her grin suggests she might even have a sense of humor. The grumbles and complaints from the usual troublemakers are surprisingly muted.

She then announces that we are going to take turns introducing ourselves. After expounding on her love of travel, her new dog, and her previous career in advertising, she turns to the girl on her right. Surreptitiously I slide my watch round to the inside of my wrist and train my eyes on the seconds flashing past. All day I have been waiting for this—final period—and now that it is here I can hardly bear it. All day I’ve been counting down the hours, the lessons, until this one. Now all that’s left is the minutes, yet they seem interminable. I am doing sums in my head, calculating the number of seconds before the last bell. With a start I realize that Rafi, the dickhead to my left, is blabbering on about astrology again—almost all the kids in the room have had their turn now. When Rafi finally shuts up about stellar constellations, there is sudden silence. I look up to find Miss Azley staring directly at me.

“Pass.” I examine my thumbnail and automatically mumble my usual response without looking up.

But to my horror, she doesn’t take the hint. Has she not read my file? She is still looking at me. “Few activities in my lessons are optional, I’m afraid,” she informs me.

There are sniggers from Jed’s group. “We’ll be here all day, then.”

“Didn’t anyone tell you? He don’t speak English—”

“Or any other language.” Laughter.

“Martian, maybe!”

The teacher silences them with a look. “I’m afraid that’s not how things work in my lessons.”

Another long silence follows. I fiddle with the corner of my notepad, the eyes of the class scorching my face. The steady tick of the wall clock is drowned out by the pounding of my heart.

“Why don’t you start off by telling me your name?” Her voice has softened slightly. It takes me a moment to figure out why. Then I realize that my left hand has stopped fiddling with the notepad and is now vibrating against the empty page. I hurriedly slide my hand beneath the desk, mumble my name, and glance meaningfully at my neighbor. He launches eagerly into his monologue without giving the teacher time to protest, but I can see she has backed down. She knows now. The pain in my chest fades to a dull ache and my burning cheeks cool. The rest of the hour is taken up with a lively debate about the merits of studying Shakespeare. Miss Azley does not invite me to participate again.

When the last bell finally shrieks its way through the building, the class dissolves into chaos. I slam my textbook shut, stuff it into my bag, get up, and exit the room rapidly, diving into the home-time fray. All along the main corridor overexcited pupils are streaming out of doors to join the thick current of people; I am bumped and buffeted by shoulders, elbows, bags, feet. . . . I make it down one staircase, then the next, and am almost across the main hall before I feel a hand on my arm.

“Whitely. A word.”

Freeland, my form tutor. I feel my lungs deflate.

The silver-haired teacher with the hollow, lined face leads me into an empty classroom, indicates a seat, then perches awkwardly on the corner of a wooden desk.

“Lochan, as I’m sure you are aware, this is a particularly important year for you.”

The A-level lecture again. I give a slight nod, forcing myself to meet my tutor’s gaze.

“It’s also the start of a new academic year!” Freeland announces brightly, as if I needed reminding of that fact. “New beginnings. A fresh start . . . Lochan, we know you don’t always find things easy, but we’re hoping for great things from you this term. You’ve always excelled in written work, and that’s wonderful, but now that you’re in your final year, we expect you to show us what you’re capable of in other areas.”

Another nod. An involuntary glance toward the door. I’m not sure I like where this conversation is heading. Mr. Freeland gives a heavy sigh. “Lochan, if you want to get into UCL, you know it’s vital you start taking a more active role in class. . . .”

I nod again.

“Do you understand what I’m saying here?”

I clear my throat. “Yes.”

“Class participation. Joining in group discussions. Contributing to the lessons. Actually replying when asked a question. Putting your hand up once in a while. That’s all we ask. Your grades have always been impeccable. No complaints there.”

Silence.

My head is hurting again. How much longer is this going to take?

“You seem distracted. Are you taking in what I’m saying?”

“Yes.”

“Good. Look, you have great potential and we would hate to see that go to waste. If you need help again, you know we can arrange that. . . .”

I feel the heat rise to my cheeks. “N-no. It’s okay. Really. Thanks anyway.” I pick up my bag, sling the strap over my head and across my chest, and head for the door.

“Lochan,” Mr. Freeland calls after me as I walk out. “Just think about it.”

At last. I am heading toward Bexham, school rapidly fading behind me. It is barely four o’clock and the sun is still beating down, the bright white light bouncing off the sides of cars, which reflect it in disjointed rays, the heat shimmering off the tarmac. The high street is all traffic, exhaust fumes, braying horns, schoolkids, and noise. I have been waiting for this moment since being jolted awake this morning, but now that it is finally here I feel strangely empty. Like being a child again, clattering down the stairs to find that Santa has forgotten to fill up our stockings; that Santa, in fact, is just the drunk on the couch in the front room, lying comatose with three of her friends. I have been focusing so hard on actually getting out of school that I seem to have forgotten what to do now that I’ve escaped. The elation I was expecting does not materialize and I feel lost, naked, as if I’d been anticipating something wonderful but suddenly forgot what it was. Walking down the street, weaving in and out of the crowds, I try to think of something—anything—to look forward to.

In an effort to shake myself out of my strange mood, I jog across the cracked paving stones past the litter-lined gutters, the balmy September breeze lifting the hair from the nape of my neck, my thin-soled sneakers moving soundlessly over the sidewalk. I loosen my tie, pulling the knot halfway down my chest, and undo my top shirt buttons. It’s always good to stretch my legs at the end of a long, dull day at Belmont, to dodge, skim, and leap over the smeared fruit and squashed veg left behind by the market stalls. I turn the corner onto the familiar narrow road with its two long rows of small, run-down brick houses stretching gradually uphill.

It’s the street I’ve lived on for the past five years. We only moved into the council house after our father took himself off to Australia with his new wife and the child support stopped. Before then, home had been a dilapidated rented house on the other side of town, but in one of the nicer areas. We were never well-off, not with a poet for a father, but nonetheless, things were easier in so many ways. But that was a long, long time ago. Home now is number sixty-two Bexham Road: a two-story, three-bedroom, gray stucco cube, thickly sandwiched in a long line of others, with Coke bottles and beer cans sprouting among the weeds between the broken gate and the faded orange door.

The road is so narrow that the cars, with their boarded-up windows or dented fenders, have to park with two wheels on the curb, making it easier to walk down the center of the street than on the sidewalk. Kicking a crushed plastic bottle out of the gutter, I dribble it along, the slap of my shoes and the grate of plastic against tarmac echoing around me, soon joined by the cacophony of a yapping dog, shouts from a children’s soccer game, and reggae blasting out of an open window. My bag bounces and rattles against my thigh and I feel some of my malaise begin to dissipate. As I jog past the soccer players, a familiar figure overshoots the goalpost markers and I exchange the plastic bottle for the ball, easily dodging the pint-size boys in their oversize Arsenal T-shirts as they follow me up the road, yelping in protest. The blond firework dives toward me, a towheaded little hippie with hair down to his shoulders, his once-white school shirt now streaked with dirt and hanging over torn gray trousers. He manages to get ahead of me, running backward as fast as he can, shouting frantically, “To me, Loch, to me, Loch. Pass it to me!”

With a laugh I do, and whooping in triumph, my eight-year-old brother grabs the ball and runs back to his mates, yelling, “I got it off him, I got it off him! Did you see?”

I slam into the relative cool of the house and sag back against the front door to catch my breath, brushing the damp hair off my forehead. Straightening up, I pick my way down the hallway, my feet automatically nudging aside the assortment of discarded blazers, book bags, and school shoes that litter the narrow corridor. In the kitchen I find Willa up on the counter, trying to reach a box of Frosted Cheerios in the cupboard. She freezes when she sees me, one hand on the box, her blue eyes wide with guilt beneath her fringe. “Maya forgot my snack today!”

I lunge toward her with a growl, grabbing her round the waist with one arm and swinging her upside down as she squeals with a mixture of terror and delight, her long golden hair fanning out beneath her. Then I dump her unceremoniously onto a kitchen chair and slap down the cereal box, milk bottle, bowl, and spoon.

“Half a bowlful, no more,” I warn her with a raised finger. “We’re having an early dinner tonight—I’ve got a ton of homework to do.”

“When?” Willa sounds unconvinced, scattering sugar-coated hoops across the chipped oak table that is the centerpiece of our messy kitchen. Despite the revised set of house rules that Maya taped to the fridge door, it is clear that Tiffin hasn’t touched the overflowing trash bins in days, that Kit hasn’t even begun washing the breakfast dishes piled up in the sink, and that Willa has once again mislaid her miniature broom and has only succeeded in adding to the crumbs littering the floor.

“Where’s Mum?” I ask.

“Getting ready.”

I empty my lungs with a sigh and leave the kitchen, taking the narrow wooden stairs two at a time, ignoring Mum’s greeting, searching for the only person I really feel like talking to. But when I spot the open door to her empty room, I remember that she is stuck at some after-school thing tonight and my chest deflates. Instead I return to the familiar sound of Magic FM blasting out of the open bathroom door.

My mother is leaning over the basin toward the smeared, cracked mirror, putting the finishing touches on her mascara and brushing invisible lint off the front of her tight silver dress. The air is thick with the stench of hair spray and perfume. As she sees me appear behind her reflection, her brightly painted lips lift and part in a smile of apparent delight. “Hey, beautiful boy!”

She turns down the radio, swings round to face me, and holds out an arm for a kiss. Without moving from the doorway, I kiss the air, an involuntary scowl etched between my brows.

She begins to laugh. “Look at you—back in your uniform and almost as scruffy as the kiddies! You need a haircut, sweetie. Oh dear, what’s with the stormy look?”

I sag against the door frame, trailing my blazer on the floor. “It’s the third time this week, Mum,” I protest wearily.

“I know, I know, but I couldn’t possibly miss this. Davey finally signed the contract for the new restaurant and wants to go out and celebrate!” She opens her mouth in an exclamation of delight and, when my expression fails to thaw, swiftly changes the subject. “How was your day, sweetie pie?”

I manage a wry smile. “Great, Mum. As usual.”

“Wonderful!” she exclaims, choosing to ignore the sarcasm in my voice. If there’s one thing my mother excels at, it’s minding her own business. “Only a year now—not even that—and you’ll be free of school and all that silliness.” Her smile broadens. “Soon you’ll finally turn eighteen and really will be the man of the house!”

I lean my head back against the doorjamb. The man of the house. She’s been calling me that since I was twelve, ever since Dad left.

Turning back to the mirror, she presses her breasts together beneath the top of her low-cut dress. “How do I look? I got paid today and treated myself to a shopping spree.” She flashes me a mischievous grin as if we were conspirators in this little extravagance. “Look at these gold sandals. Aren’t they darling?”

I am unable to return the smile. I wonder how much of her monthly wage has already been spent. Retail therapy has been an addiction for years now. Mum is desperate to cling on to her youth, a time when her beauty turned heads in the street, but her looks are rapidly fading, face prematurely aged by years of hard living.

“You look great,” I answer robotically.

Her smile fades a little. “Lochan, come on, don’t be like this. I need your help tonight. Dave is taking me somewhere really special—you know the place that’s just opened on Stratton Road opposite the movie theater?”

“Okay, okay. It’s fine—have fun.” With considerable effort I erase the frown and manage to keep the resentment out of my voice. There is nothing particularly wrong with Dave. Of the long string of men my mother has been involved with ever since Dad left her for one of his colleagues, Dave has been the most benign. Nine years her junior and the owner of the restaurant where she now works as head waitress, he is currently separated from his wife. But like each of Mum’s flings, he appears to possess the same strange power all men have over her, the ability to transform her into a giggling, flirting, fawning girl, desperate to spend her hard-earned cash on unnecessary presents for her “man” and tight-fitting, revealing outfits for herself. Tonight it is barely five o’clock and already her face is flushed with anticipation as she tarts herself up for this dinner, no doubt having spent the last hour fretting over what to wear. Pulling back her freshly highlighted blond perm, she is now experimenting with some exotic hairdo and asking me to fasten her fake diamond necklace—a present from Dave—that she swears is real. Her curvy figure barely fits into a dress her sixteen-year-old daughter wouldn’t be seen dead in, and the comment “mutton dressed as lamb,” regularly overheard from neighbors’ front gardens, echoes in my ears.

I close my bedroom door behind me and lean against it for a few moments, relishing this small patch of carpet that is my own. It never used to be a bedroom, just a small storage room with a bare window, but I managed to squeeze a camp bed in here three years ago when I realized that sharing a bunk bed with siblings had some serious drawbacks. It is one of the few places where I can be completely alone: no pupils with knowing eyes and mocking smirks; no teachers firing questions at me; no shouting, jostling bodies. And there is still a small oasis of time before our mother goes out on her date and dinner has to get under way and the arguments over food and homework and bedtime begin.

I drop my bag and blazer on the floor, kick off my shoes, and sit down on the bed with my back against the wall, knees drawn up in front of me. My usually tidy space bears all the frantic signs of a slept-through alarm: clock knocked to the floor, bed unmade, chair covered with discarded clothes, floor littered with books and papers, spilled from the piles on my desk. The flaking walls are bare, save for a small snapshot of the seven of us, taken during our final annual holiday in Blackpool two months before Dad left. Willa, still a baby, is on Mum’s lap, Tiffin’s face is smeared with chocolate ice cream, Kit is hanging upside down off the bench, and Maya is trying to yank him back up. The only faces clearly visible are Dad’s and mine—we have our arms slung across each other’s shoulders, grinning broadly at the camera. I rarely look at the photo, despite having rescued it from Mum’s bonfire. But I like the feel of it being close by: a reminder that those happier times were not simply a figment of my imagination.

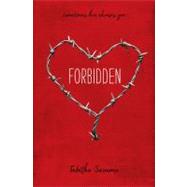

© 2010 Tabitha Suzuma