What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

ONE

Me, Ramiro Lopez

My mom says I need to stop and think about things. I think about things all the effen time. Think and think and think. You know, it's not like all that thinking has gotten me places.

Him

Sometimes I think of him. And when I do, I start to draw a picture. Not a real picture. I'm not an artist, not even close. I just draw this picture in my head.

Of him.

My dad.

It's easier for me to draw a picture of what he looks like than to imagine his voice. I mean, I don't know what he would sound like. He would use a lot of Spanish. But his voice, I don't know, I just don't know what words he'd use. He'd be angry, but that would just make him normal. A lot of fathers are like that -- especially fathers who've gone away. I think of their anger as a wind. And that wind took them away. From me. And all the others like me.

So I draw a picture in my head. Of him. Not of his voice but of his face. He has dark eyes and thick, wavy hair that was once really black -- really black. But now his hair is more white than black because that's how it goes when men get older. Their hair begins to get old too. That's the way it is and there's nothing we can do about it. And he has lines on his face, more from working out in the sun than from laughing. He doesn't like to laugh. He looks tired because he's had to work so hard. With his body, not with his mind, not like a teacher or a doctor or an insurance guy or a computer geek. You know, like construction. Working in construction -- it makes you old and tired. It kills your body because you have to work out in the sun every day, in the heat, in the cold, every day. It's not like working out in a gym and hanging out with other jocks that have nothing better to do than to muscle up -- it's not like that. If you work with your mind, then working with your body is just a hobby. But if you work with your body, then, well, your only hobby is to rest.

"Your body is nothing but a money machine." That's what Uncle Rudy says. "That's the way it is. We're all just prostitutes." My aunt hit him when he said that and told me not to pay any attention to him.

But listen, when you work in construction, your body is the car and the road and the destination. No, no, I'm getting all tangled up in my own words. That's not right. Look, I don't agree with Uncle Rudy. I get the part about using your body to make money. But the body's not a machine. When you work with your body every day of your life, well, your body's more like a punching bag -- it gets hit all the time. All day. Every day. And it's never going to stop. Not ever. I know. I hear men talk -- and they say things about their tired bodies, things like: "Ya estoy pa la patada." Mexican working guys, they talk like that. My dad's one of those guys. I know. He didn't go to college or anything like that. He didn't even graduate from high school. My Tía Lisa told me that once. She likes to tell me things I'm not supposed to know.

In the picture I've drawn in my head, my dad looks sad. Tired and sad and maybe mad, too. Definitely mad as hell. That's not a good combination. You don't see the anger in his body or his face. But if you look into his dark eyes, that's where you see all the anger -- they're like a bomb about to go off. You can almost hear the tick tick tick.

Yeah, he's mad as hell.

Mad at the world.

Mad at himself.

Mad at my mom.

Mad because he was born a poor Mexican. Mad because he never finished high school. Mad because he got a rotten deal. He thinks the world cheated him. And maybe the world did cheat him. But I don't think he helped himself out. I mean, my Uncle Rudy says, "If you know a man's gonna cheat you, then why the hell are you lending him twenty bucks?" No, I don't think my dad helped himself out. See, the way I picture him, he has so much anger in his eyes, that he's half-blind. He can't see straight. He can't see the leaves on a tree. He can't see the fact that some dogs know how to smile. That's what happens. When you get too angry you can't see the world anymore.

My dad, he looks down at the ground more than he looks up at the sky. It's like he doesn't even notice the birds anymore. He's just looking down at things that crawl. That's how I draw him -- his eyes never looking up.

He's crooked now. He's all dented up. He's a car that's been on the road too long. Too many accidents. The paint's all peeled off.

He used to be handsome. Real, real handsome. Girls used to look at him, praying he'd look back. And his walk was like a dance. I guess we always want our dads to be handsome just like we want our moms to be beautiful. But now I'm thinking he's changed and he's more than just an ordinary handsome guy. Now he has the most interesting face in the world. Maybe interesting is better than handsome. But interesting doesn't mean happy, and I mean he looks beat-up as an old, chained-up dog. And disappointed, as if somehow a part of him is missing. Me. It's me that's missing. He's thinking of me and he's missing me, and sometimes he looks out at the sky and whispers my name and tries to imagine me just like I'm imagining him.

Look, I don't know what I'm talking about. It's not as if I really know what he looks like because I've never seen him. My mother once said he was beautiful. "He was like an ocean -- beautiful to look at." The way she said that, right then she looked soft as a cloud. And then all of a sudden she turned real hard. "I almost drowned in that ocean." I knew she wasn't about to go near another man ever again. All men had become oceans she might drown in.

Once, when we'd gone to my cousin's wedding, my mom looked at me and said. "I ripped up all our wedding pictures -- and then I burned them." She looked at me like maybe she was sorry she'd blurted that out, and she gave me a look like I wasn't supposed to be asking her any questions about him. Him. I don't think she blurted out that piece of information to be mean. I think sometimes our minds get so full of something that we just have to empty them out. I think that's what happened to her. Sure. That's a good theory. I mean, she sounded so mad when she said that. Really, really mad. Not mad at me, but mad at the way things had turned out -- and well, sad, too. It's as if some of my dad's anger and some of his sadness rubbed off on my mother every time he touched her. And I know she carries his face somewhere inside her (and for all I know, somewhere in her purse). I mean, you can't rip up all the pictures you carry in your head. You can't. Even if you want to. I think sometimes she cries for him. But she doesn't cry in front of me or my little brother. My little brother, Tito, wasn't even born when he left. He was still inside her. And I was almost two.

I sometimes try to imagine him on the day he left. I see him packing all his clothes. I see him looking around the room -- trying to figure out what else he should pack in his suitcase. Maybe he thinks he should stay, but he knows he has to go. I picture him with a confused look on his face and I picture my mother sitting in the kitchen. Saying nothing. Just waiting. Waiting for him to leave so she can have herself a good cry. I wonder if he said good-bye to us and said something to us, you know, like fathers do, talk to their sons, tell them things. Important things like I'll miss you, I'll think of you every day, I'll come back, you'll see, I'll come back, and don't ever forget that I love you, hijito de mi vida. I don't know. Maybe he just left. Maybe he didn't say a damn thing.

My dad must have held me in his arms when I was a baby. He must have kissed me like I see other fathers kiss their babies. He must have done that.

His breath might have smelled of cigarettes and garlic.

His breath might have smelled like cilantro.

His breath might have smelled like too much anger and work.

But there might have been something sweet on his breath. He might have taken me to the grocery store or to wash his car at the H & H or taken me for a ride to get ice cream at the 31 Flavors, and he probably took me to the El Paso Zoo and to the swimming pool at Memorial Park and to Western Playland and to get empanadas at Gussie's and to get tacos at Chico's -- places like that. He might have taken me to watch the Diablos play baseball or to a Miners football game. He might have. Just because I don't remember doesn't mean it didn't happen.

Me, Jake Upthegrove

All I'm trying to do is talk to you. Are you listening? See, the thing is, I don't think you are listening. Okay, see, we have a problem. You don't think I want to talk and I don't think you want to listen.

Me

(Jake Upthegrove)

"Hey, Upthegrove! Someday you'll be sent up the river." That was the first joke I ever heard about my last name. I don't even remember who said it, and back then I didn't even know what the expression "being sent up the river" meant. I was five years old. Okay, it was supposed to be a joke -- but I just didn't get it. All I remember was that some guy was barking a joke at me. I mean, c'mon, let's get down to it, people are like dogs. Let me tell you something, if a dog acts like a dog, well, that's a beautiful thing. That's very cool. I can dig that. I can really dig that. But if a human being acts like a dog, well, that's not a beautiful thing. Definitely not cool.

Another time, a girl in second grade called me "Up the Street." Got a real laugh out of that one. I mean, I was so destroyed. And if that wasn't enough, the next day she accosted me with "Down the Road." That girl was real stand-up material. There's something about my name that people just can't leave alone. It's like a kitty they have to pet or a shoe they just have to try on. People always fall into calling me by my last name. It feels like I've always been in the Army. Everybody's a drill sergeant. And me, I'm permanently assigned to be in boot camp all my life. Okay, look, maybe that doesn't qualify as abuse but it doesn't qualify as affection either. People just destroy me.

When I was a freshman in high school, I got into my first fistfight. "Hey Upthegrove!" Some guy was yelling my name. I turned around and there in front of me was this guy named Tom. Hated him, that guy. I mean guys like that really destroy me. He was one of those kinds of dudes that dressed down in ratty clothes, torn T-shirts, ripped jeans, and had tattoos all over the place. He liked to make out like he was poor and lived in a tough neighborhood. But who the hell could afford that kind of body art if you weren't fucking rich?

"Upthegrove!" he taunted, singing my name like it was a piece of wadded-up paper he was swatting around in the air. "Upthegrove," he sang, "what kind of shit name is that?" I turned around, my fist closed tight, and pounded him right in the face. Didn't even know I was going to do that.

When I pulled back my fist, I could see blood pouring from Tom's face. Blood is more real than any tattoo, I'll tell you that. It sort of scared me at first -- but then the thought came to me that he wasn't exactly going to die on me. Maybe his nose was broken or something -- but he was going to be just fine. See, in situations like this, it's always best to take the long view of things. In the short term he was bleeding and hurting. In the long term he was going to be just fine.

So, there's Tom holding his bloody nose and looking like maybe he was going to cry, and there was red all over his ratty shirt. I wasn't about to let go, though, no sir, I was in this and I was going for all the marbles, so I just looked at him and said, "Fuck you. And fuck your rich dad, and fuck your expensive tattoos, and fuck your rich bitch of a dog." I don't know why I said that. I mean, I don't think dogs know anything about being rich or poor and I have a soft spot for dogs, especially girl dogs because they don't go around screwing up the world and they tend to be loyal and sweet, and the part about his dad, maybe I should have left that out -- I mean, I'm not exactly living in squalor. On the other hand, his father didn't get to be where he was by being the world's nicest guy -- so maybe I was glad I'd dragged him into the whole discussion. Not that any of this qualified as a discussion.

Anyway, not a second later, his loyal, boot-licking, dumb-ass sidekick, John, jumped in swinging. I mean, the guy was ready to party. His fists were a pair of shoes on a dance floor -- and me, well, I was the dance floor. I'll spare you all the pretty details. It was over quick. That was the good part. I had to have stitches above my left eye, and I don't think my lower left rib will ever be the same. And believe me, I saw stars -- the big dipper, the little dipper, and some constellations I didn't even know existed. Stars. Shit. I mean, can you dig that? I suppose I should thank the guy for showing me a universe I didn't know existed.

That was my first and last fight. The one thing I learned on that day was that I was better at using words than using my fists. Live and learn, you know? I mean, even if you can't dig the fact that I popped a guy right in the nose, you can dig the fact that I learned something.

I was in deep trouble at home and at school. We're talking seriously deep trouble. Profoundly deep trouble. No video games. No television. No movies. No going out. No allowance. No reading e-mails, no downloading music, no hanging out with people I liked. No leaving the house without being accompanied by an adult. I told my mom I didn't think she qualified as an adult. I got in even deeper. She looked right at me and said, "That's it. Your life is ruined."

"Sure," I said. "Wow. Ruined. I'm so destroyed."

"I hate that expression," she said. "I wish you'd stop using it."

"Okay," I said, "Make a list, okay? Just list all the expressions I use that you wish I'd stop using. I'll take the list, read it over, and take it under advisement."

She pointed her finger -- which meant I should go to my room. She walked in behind me and confiscated my iPod and took away my laptop.

So there I was, alone, with no electronic devices to comfort me. For a whole month.

Well, at least I read all those books I was supposed to be reading. I didn't mind. And then there was the whole thing of talking to counselors and my mother asking me for days at a time, "What's wrong with you? Don't you know you could wind up in jail? And you don't even know Spanish." I tried to keep from rolling my eyes. See, I actually do speak some Spanish, and I'm always translating for her -- her (my mother, the woman who just told me that I didn't speak Spanish) -- when she wants Rosario, our housekeeper, to do this and that. This fact was apparently lost on her. But see, the point here is that my mom happens to believe that jails are full of Mexicans who don't speak English. She has these ideas -- though sometimes the things she says don't actually qualify as ideas. She destroys me.

And then I smiled and said, "Hey, Mom, they have special sections in jails for gringos." And then she gives me this look -- that don't-interrupt-me-don't-mock-me-have-some-respect look. She patted her chest (her favorite gesture) and finally said, "You're very glib."

I decided it was best to just zip it up. And my mom, just as she stopped patting her chest, she let it rip, and she's going on and on about rights and responsibilities and I swear her little lecture even had something in it about the Constitution -- and my stepfather is shaking his head but also trying to calm my mother down and trying to smile at me -- and he has this stupefied look on his face like a fish who's caught in a net, all pained and confused -- poor guy, and he keeps telling me that this is not easy for him and I want to tell him that really the whole thing has nothing to do with him, but I don't say anything because, well, I'm already in a helluva lot of trouble, and the truth of the matter is that I just don't see things their way. They weren't even there when I decided to rearrange Tom's nose. I mean, what did they have to go on except hearsay?

Look, all they have is this parent perspective thing. They have this image of themselves as having a more global view of things, like they really see the big picture. Right, right, sure. I mean, can you dig that? Let's look at the big picture by all means. Let's put it this way: I am not responsible for all the chaos in the world. I am not responsible for dudes with attitudes and the twisted, grotesque things they have in their screwed-up heads. Please. Someone help me out here. And even though there's no excuse for going around hitting people so hard that you draw blood, there's also no excuse for bullshit bullies with pedestrian names like Tom and John. And when we all grow up to be forty, who the hell do you think is going to be screwing people over? Me? Or Tom and John? Now you're getting the picture. I'd say my long-term perspective is pretty global.

So, the whole thing about punching Tom got really involved and complicated. Of course it did. I mean, there were adults involved. We know what happens when adults step in. They have to be in charge. They have to have a plan. They like plans. Not that they ever work -- but coming up with a plan feels like they've done something. You know, I don't see that the adults around me have done such a hot job of running things. Nope, not in my opinion. Adults, they really destroy me.

The thing is, just because they all go to work and bring in some cash, they figure they know how to run the world. Well, take a look around. Global warming, pollution, poor people without health insurance, bad schools, bad streets, underpaid teachers, overpaid insurance lawyers, and gasoline prices that are as high as Katie Scopes at a party. (Katie Scopes, I like her, but, hell, she's always stoned -- probably due to the fact that adults are running the world). Look, I could get a list going here that could get really long -- I'm talking seriously long. Dig it? So, anyway, without asking my opinion, the adults took over "the situation." That's what the principal said when he called my mom: "We have a situation here." The principal, he really destroys me.

In the end, the adults proposed a "solution" to "the situation." There were apologies from me and apologies from Tom and John, none of them sincere, though no one seemed to give a damn about sincerity. See, I get criticized for being glib and ironic all the time. Well, when I try sincerity, you want to know what happens? I get stepped on like an ant. Like a worm. Like a cockroach. Bring on the irony, that's what I say. I'm sure you can dig that.

So, of course detention was part of the solution. We had to write essays about how we wound up there. I had to write mine again because I was told that the "tone of my essay lacked a genuine sense of remorse." I see, I said to myself, we can live without sincerity but we cannot live without remorse. I told Mr. Alexis, the principal, that if the president of the United States could start a war in Iraq on false pretenses of WMDs and didn't have to apologize for his big fat lies, then there was no reason to expect more from a worthless, out-of-control anarchist like me.

Mr. Alexis put on this stone face and looked right at me. He told me I hadn't earned the right to speak that way about the president of the United States who was a decent, Christian man. And, in addition, he informed me that I didn't have a nickel's worth of knowledge about the serious philosophy of anarchism. I explained -- disrespectfully, I'm sure -- that my opinions of the president were at least based on something that resembled reality, and even if they weren't, I was entitled to them and would he please keep his well-intentioned but small-minded lectures defending our nation's political leaders to himself. I didn't stop there. Of course I didn't. I just felt I had to add that I probably had a better idea of the serious philosophy of anarchy than a man like him whose addiction to order seriously undermined his feeble attempts at engaging his imagination.

He returned my remark by reminding me that he remained unimpressed with my shallow intellectual demeanor and that nothing could disguise my obstinate, disrespectful, and undisciplined attitude. He said being a smart aleck didn't actually make me smart. And then he said it again: "Despite your extensive, if aggressive vocabulary, you're nothing but an angry, disrespectful young man who needs a little discipline." You see, the thing with adults is that respect is just a word they use to guilt us nonadults into doing what they want us to do. But did Mr. Alexis leave it at that? Of course not. He reminded me and Tom and John that it was a privilege to attend a pre-med magnet school and if we weren't very careful, well, we just might be sent back to a normal school. That's how he put it. A normal school. That guy, he destroys me. Where in the hell was he going to find a normal school? How can schools be normal when they're run by adults like him?

I could make the exchange between me and Mr. Alexis as long as it actually was. But it's pointless, really. He did warn me about my politics which I thought was totally out of line. "Apart from the fact that you're a completely unmanageable young man, your politics are offensive to the thinking people of this nation." I told him pretty much that I didn't think he -- or anybody of his ilk -- qualified as a thinking person. He tried to say something at that point but I just kept on going. I told him that as far as being unmanageable, well, I came to school to be taught, not to be managed. "I'm a person, not a portfolio." And then I really got myself into trouble by telling him that if he wasn't careful, I was going to make his nose look like Tom's.

He said he could throw me out of school for that threat. I said to take it up with my stepfather, the attorney (not that David would have sided with me). I eventually agreed to put more remorse into my essay. I even started to refer to him as "sir." He wasn't smart enough to pick up on the fact that I was mocking him. Look, he won the argument. I put remorse into my essay. But seasoning my essay with remorse was not the final solution that the adults around me had concocted. That was just the beginning. To put some à la mode on top of the apple pie, I was forced to attend anger management classes, where the only thing I really learned to do was to keep my mouth shut and my hands to myself. Maybe that wasn't such a bad thing to learn. And all of this because of my name. There's a lot of irony here, of course. Irony -- that's my favorite word. Look, I live in a seriously ironic world and if there is a God, I've decided irony is his favorite word too.

And to layer irony upon irony, I don't even know the guy whose name I own. I mean, I really am destroyed. I don't mean to play victim here, but c'mon. People get to make fun of me because I have a last name that got stuck on me like a permanent bumper sticker? Look, my mother left that guy -- my father -- when I was about three. In my seventeen-plus years of living, I've talked to the guy only once.

And he has never, never, never tried to communicate with me directly. Sending advice secondhand through my mother doesn't qualify as paternal involvement. Not in my book, it doesn't. I don't talk to him, I don't know him, and I don't even remember his face. What do three-year-olds remember? Ducks in a bathtub, that's what they remember. Red wagons with wheels. Books made of cardboard you could bite.

I'm not happy about any of this. Look, I'm destroyed.

Me, Ramiro Lopez

Look, just because you don't have a girlfriend doesn't mean you don't know anything about love. I know more than I want to know.

Her

Mom is a pretty lady. Even without makeup.

She's not even forty yet. I mean, that sounds old, but it's not. I mean, fifty, that's getting old -- but she's thirty-eight. She's younger than a lot of my teachers. And her sister, Tía Lisa (who's even younger) is always trying to fix her up on a date. When she brings up some guy's name as someone that might be on the market, my mom shakes her head and says things like "I've already dated a man like that once, remember?" or "I'd rather work at the Dollar Store than go out with a man like that."

Once, my Tía Lisa invited this guy over to a backyard barbecue at my uncle's house. At first, I thought it was her boyfriend. But pretty fast I got the whole scene in my head: This guy named Steve was there because my Tía Lisa met him at some party and thought he'd be perfect for my mom. All the women at the barbecue thought he was really fine and all that. They called him a "fox." Sure. I mean, women can be as bad as guys when they see good-looking guys. Believe me, I've listened to enough of that crap. This business of women falling all over themselves over a good-looking guy, nothing original there. Nope. And guys? They're the same. Hell, they're worse.

So, anyway, everyone thinks this guy, Steve, is the star on a Christmas tree. Even my Great Aunt Chepa said he was bien chulo, and she never says anything good about anybody.

But my mom wasn't that impressed. "What would I do with a man who spends more time combing his hair than I do?" My mom doesn't trip over herself for anyone.

Well, to me he seemed okay. I thought he was a gringo, but really he was mostly Mexican. You know, my uncle Rudy, he calls people who are half Mexican and half gringo "coyotes." I don't know where he got that, but that's what he calls them. He called Steve a good coyote. And you know, that guy, Steve, spoke Spanish and everything like that, and he seemed to be a regular Joe. And I think he really liked my mom, the way he looked at her when she talked which really made me a little bit, well, you know, I didn't like that. Look, she's my mom. I know she had to have sex in order to have me and my brother, Tito, but I don't think it's a very good idea to think about those kinds of things. I mean, it's not normal. Not that I know that much about normal. Look, I don't know anything about normal. But I know what's not normal. So, when this guy is looking at my mom in a certain way -- you know which way -- well, I didn't like that much. Not much, nope, just didn't like that.

But look, the guy was decent. He had a job and didn't seem like a pervert or anything like that, and he didn't give me the creeps, and he even asked me all kinds of questions, like where did I go to school and did I have a girlfriend and what kind of music did I like. He was trying real hard. He wasn't so bad. And he liked to say "cat," which I liked. I mean, he'd refer to people as cats. This cat did this. And this cat did that. And when he was talking about the Beatles, he said he really liked those "cats." And I thought that was a very cool way of talking. My Tía Lisa said it was "fantastically retro." But, you know, retro's not necessarily bad. Yeah, that cat was okay.

But I got to thinking that maybe that cat might start hanging around a lot. I wasn't sure what to think about that. I mean, it's not as if I want a father. I have a father. It's just that I don't know who he is or where he is. But I have one. I didn't want any proxies. Proxy, that's a cool word. That's what my friend Louie says about girls he takes out. "They're all proxies," he says, "cuz the real one, she won't go out with me." He's funny. He's always in love with girls who don't love him back. So, the poor guy is stuck with proxies. I'm not like Louie. I don't do the proxy thing.

I know that if my mom ever got interested in another man, well, that wouldn't necessarily mean she was looking for a father for me and Tito. Maybe it would only mean that she still had a heart and that she wasn't dead and that she didn't like being alone. Women don't like being alone. I hear them talk. But sometimes they'd rather be alone than be with a real creep. Creep, I like that word. It's been around awhile -- that's why I like it. You know, maybe I'm a little bit like that guy Steve. I like retro. Anyway, like my Tía Lisa says, "Creeps are a dime a dozen. Mejor sola que mal acompañada." But my Tía Lisa also says: "Everybody needs to be loved -- even mothers," and then she bops me on the head. I'm crazy about my Tía Lisa.

But, you know, I don't think I need to worry too much about my mom and other men. She's just not ready. "Your dad left her wounded." That's what my Tía Lisa says. When I think of wounded, I think of dogs that have been run over. But a dog doesn't always die when he's been hit by a car. Sometimes the dog recovers and lives a normal dog life. I've even seen dogs with three legs hop a fence.

Mom never says much about what went wrong between her and my dad. She just says, "He left us one day." I know a part of her wants to talk about it -- about everything. But a part of her is used to being quiet. Not talking about things is an addiction. I didn't make that up. I heard some woman say that to her friend at the Big 8 grocery store as she tried to decide which avocado she wanted to buy. She said, "Dios mio, these avocados are terrible, and my good-for-nothing husband, he's addicted to television and to silence. That husband of mine, he just doesn't talk. Así son, that's the way they are. They won't talk." And her friend says, "It hurts men too much to talk, so they just sit there and watch television. But just get them into a bar with all their no-good, beer-guzzling boracho friends, and hell, they talk so much their lips get sore." They both nodded at each other as they picked just the right avocado.

But the thing is, it's not just men who are addicted to not talking. It's women too. It's like the flu. Everyone gets it -- and then they just pass it on. My mom, she has that flu. Maybe she's passed it on to me. For sure she's passed it on to Tito. He'd rather be hit by an effen hammer than to tell you what he's thinking. He's seriously addicted to not talking.

Mom works as an assistant nurse to a doctor. "We do okay," she says. That means we have enough money to get by. And we have a good doctor because her boss, Dr. Gómez, he'll always see us for free. Or close to free, anyway. "And that's a lot," my mother says. "There's a lot of people in the world who never see a doctor because they just don't have the money." She's proud. But she can be hard, too. She says if you didn't earn something, well, then you just shouldn't have it. With her, you have to earn everything. It's like life is a job, and you don't even get paid for it. But she's soft too, my mom. I like that about her, she can be hard and she can be soft. It makes her interesting. I never know which part of her is going to be in the kitchen -- the hard Mom or the soft one. Sometimes, I get tired of trying to guess which Mom is going to show up.

"Life is up and down," my Tía Lisa says. She's the kicks. I mean the real effen kicks. She's about ten years younger than my mother and sometimes she looks like she's still a girl, and she's always smoking a cigarette and she's always talking about life. Life is this and life is that, and life, life, life, life. I never heard anyone talk about life so much. "Be good to your mom," she says, "life's been hard on her. You know, your dad was never good to her. She didn't deserve that." I think she wants to tell me all sorts of things about them, but she always winds up changing the subject. Usually, the subject she changes back to is life. Life this and life that. "Life is always better with a cup of coffee." She likes saying that. I wouldn't give you a dime for a cup of coffee. Not a dime. Not a nickel. Tastes like a pigeon crapped in your mouth. I pretty much stick to orange juice. Cherry Cokes sometimes.

We have our own house on Calle Concepción. It's a white house that my mother wants to paint another color. She just can't seem to decide on the color -- so it's kind of stayed white by default. I got that expression from Mrs. Herrera, my English teacher. She loves to say that. She says things like "Mr. Lopez, you're the best student in this class by default." Which means that she thinks we're just a bunch of dumb-ass Mexicans good for nothing but flipping burgers and making breakfast burritos at Whataburger, and that I'll grow up to be one of the better burrito-makers. Yup, that's what she pretty much thinks, we're all a bunch of burrito guys. Well, hell, I do work at Whataburger. I flip a good burger. But that's only a part-time job and it's only temporary. Screw Mrs. Herrera.

Our house is pretty close to Thomas Jefferson High School -- but we just call our school "La Jeff." That's what we say, "I go to La Jeff." And our rival school, well, that would be "La Bowie." We're foxes and they're bears, and, hell, my friend Lalo, he says we're just a bunch of animals. And then he starts laughing his stupid animal he She knew it was a good sign. She says I was born with two strikes against me -- I was a poor Mexican and I didn't have a father. But this summer she took me aside and said, "You've done a beautiful job, hijo de mi vida. You're on third base, now." My mom, she loves baseball. I don't know where she got that, because a lot of girls don't like sports, but my mother, she loves baseball. She likes the Dodgers and the Cubs and secretly she likes the Yankees but they win too much, and she normally doesn't like people and teams who win more than their fair share of the time. So now my mom says I'm on third base. It means I'm about to score. It means I might be going somewhere. Father or no father, I might be going somewhere.

But where? What happens after you reach home plate?

I worry about my mom. I don't know if she'll be all right when I'm gone. I worry about my little brother too. He's gotten into smoking pot. Other stuff too. All that stuff that messes with his head, he thinks it's the effen kicks. Yeah, sure, I tell him, the real effen kicks. I tell him all that crap is gonna beat the holy hell out of him so bad that he'll never think straight again. Tito just smiles like I'm full of all that leftover grease from the grill at WhataBurger. And then he says if I tell Mom, he'll kick my ass all the way to Denver. I laugh. I mean, I don't even think Tito knows where Denver is.

I keep an eye out, and I drag Tito's good-for-nothing ass home when I need to. And every day I tell him to cut that shit out. And every day he gives me those looks like he'd really like to hurt me. Those eyes are stone. And they hate. But I'm not afraid of those eyes. And I tell him that it's him who doesn't know his skinny brown ass from a store-bought tortilla. Tito, he goes through my closets and asks me which shirts I don't wear anymore, so he can take them and sell them and try to score some dope. He takes my shoes even when they're still good and my pants -- anything he can get his hands on. And sometimes he steals other people's old clothes too. I followed him once to one of those places that sell used clothes by the pound. The border's full of those places. And pawn shops and loan shops that screw people. So my little brother, he's learned how it all works. He's become a regular little entrepreneur so he can score some pot. A regular little capitalist trying to make the most of whatever capital he has. Capital. It's a new thing for me. I'm studying basic theories of economics. My brother, Tito, doesn't have to take that class. He knows all the basic rules already.

My mom took me to one of those loan shark places once. It was called Border Loan Company. Their motto was "Money for the people." She said it was time I learned a few things -- so she took me there and pretended to want a loan of five hundred dollars. She took the paperwork as some guy who was wearing way too much cologne was trying to make her sign. She said she wanted to read the contract. He said he could tell her what it said. She looked at him and said she'd like to take it home.

When we walked out, she looked at me and smiled. "Never trust a man who smells nicer than your mother." We both laughed. I liked to do that, laugh with my mother. When we got home, she showed me how she would've had to pay three times the amount of the loan because of the interest they charged. And then she took me to a real bank. She got a real loan there. A home-improvement loan. She said she could redo the bathroom and the kitchen, get a new stove and a new refrigerator and new cabinets, and paint the house with that loan. She took me through the whole thing. It was an education all right. I asked her how come those loan shops were allowed to do stuff like that to poor people. She said that half the rich people in the world got rich off the poor, and that was the God's honest truth. And since those same rich people ran the world, why on God's good earth did I think the whole messed-up system was going to change? My mom gets really angry about things like that. But the thing is, she's not angry at me and my brother.

She's great, my mom. Even when she's being strict, I know she's keeping her eye on the ball. I know a lot of guys, and they're always pissed off at their mothers. Not me.

I wish my dad would have seen what kind of woman she was. He wouldn't have left her. He'd have stayed with her forever.

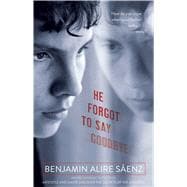

Copyright © 2008 by Benjamin Alire Sáenz