Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

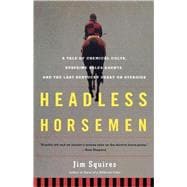

Jim Squires is the author of Horse of a Different Color, an account of his wild ride as the breeder of Monarchos, the winner of the 2001 Kentucky Derby. He has been breeding and raising horses since 1977, thoroughbreds in Kentucky since 1990, and was the editor of the Chicago Tribune from 1981 to 1989. He lives in Versailles, Kentucky.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.