Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

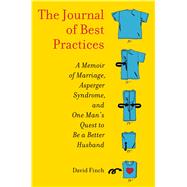

| IntroductionùDo all that you can to be worthy of her love | p. 1 |

| Be her friend, first and always | p. 21 |

| Use your words | p. 39 |

| Get inside her girl world and look around | p. 57 |

| Just listen | p. 69 |

| Laundry: Better to fold and put away than to take only what you need from the dryer | p. 89 |

| Go with the flow | p. 105 |

| When necessary, redefine perfection | p. 123 |

| Be loyal to your true stakeholders | p. 141 |

| Take notes | p. 159 |

| Give Kristen time to shower without crowding her | p. 171 |

| Be present in moments with the kids | p. 185 |

| Parties are supposed to be fun | p. 197 |

| The Final Best PracticeùDon't make everything a Best Practice | p. 217 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 223 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Introduction

Do all that you can to be worthy of her love.

I was thirty years old and had been married five years when I learned that I have Asperger syndrome, a relatively mild form of autism. My wife, Kristen, a speech therapist and autism expert, brought it to my attention one evening after harboring suspicions for years.

Receiving such a diagnosis as an adult might seem shocking and unsettling. It wasn’t. Eye-opening, yes. Life-changing, yes. But not distressing in the least. Strangely, it was rather empowering to discover that I had this particular condition. In fact, the diagnosis ultimately changed my life for the better.

I received the news the day before my niece was born. I remember this not because I’m a wonderful uncle but because she was born on March 14, 2008, which is well-known among my fellow nerds in the math and science communities as “Pi Day” because pi, the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, is equal to 3.14. Also 3 + 14 + 2 + 0 + 8 totals 27, which is divisible by 3, and I love numbers that are divisible by 3, particularly numbers whose digits sum to 27, of which 3 is the cube root. (Are you starting to see why Kristen had her suspicions?)

The day had been chaotic but really nothing out of the ordinary for two young working parents. Kristen was in the kitchen, trying to put it back in some kind of order, and I was upstairs saying good night to our kids. After walking with our ten-month-old son, Parker, in little circles around his dark room and whispering the lyrics of an Eric Clapton song until he fell asleep, I cuddled with our daughter, Emily, until her restless two-year-old squirming subsided and her breathing slowed and deepened. I crept out, whispering “I love you,” the words all but dissolving into the whir of her electric fan.

As I descended into the warm amber glow that bathed the first floor of our house, I could hear the hum of the dishwasher in the kitchen and the soft clunk of toys being put away in the playroom. Something was up; the house was never so tranquil right after the kids went to bed. Usually, the television was on, the kitchen was a disaster, and books and toys were scattered everywhere. I expected to find Kristen in her usual spot: sitting on the couch among stacks of paper and thick binders, her laptop resting on her legs as she feverishly prepared for the next day’s work. But everything was different that night.

In the kitchen, my dinner was cooling on the clean counter, and I felt an unusual sense of peace as I prepared for my evening routine. At eight thirty each night, after the kids have been put to bed, I circle the first floor, counterclockwise, starting in the kitchen, where I check to see if the patio door is locked. Then it’s back to the kitchen, where I usually wander around in circles until Kristen asks me what I’m doing.

But that night, before I began, Kristen approached me by the refrigerator in her pajamas and wrapped me in a tight hug.

“Oh,” I said, surprised. “Hello there.” I couldn’t remember the last time she had given me a hug for no particular reason. I hesitated for a moment, trying to play it cool, then squeezed her close.

“Hi,” she said into my chest. Her blond hair darkened to a shade of honey and shimmered lightly in the dimness. “Do you want some pizza?” she asked.

“Yeah, thanks for making it.”

“Sure,” she said. “When you’re ready, why don’t you bring it down to the basement?” Without letting go, she looked up at me and smiled. “There’s something I want to show you.”

“Okay, I’ll be right down.”

Understanding the importance of my routines, she playfully patted my butt and headed down to her office in the basement. Stunned by this rare and remarkable display of affection, I completed my rounds. I proceeded through the dining room and living room, then it was on to the foyer, where I always take a few moments to stare out the front window, visually lining up the neighbors’ rooftops (the alignment is the same every time, which is so gratifying it makes my shoulders relax, and for a moment my head is clear, my thoughts organized). As usual, I took note of which lights were on. I don’t normally shut them off, I just like to check in and see how they’re doing. Dining room light on, piano lamp not on, foyer not on, hallway on, kitchen off (that’s kind of rare . . . how ’bout it, kitchen?), oven hood on. I grabbed my pizza from the counter, swiped a Pepsi from the fridge, and made my way down the loud, clunky steps to Kristen’s office in our basement, where she was sitting in front of her computer. She turned and beamed at me.

“Sit here,” she said, pointing to the empty chair beside her. I had no idea what was going on, but there was pizza involved, and for the first time in weeks, I’d made her smile. Whatever it is, I’m in.

“Ready to get down to business?” she asked in a tone that seemed to suggest that I was.

I laughed. “Wet’s get down to bwass tacks!”

“Huh?” She looked thoroughly confused.

“It’s from Blazing Saddles. I’m ready.”

Embarrassed and disappointed that my movie reference tanked, I shoved my hands under my legs and swiveled back and forth in my chair.

“All right,” she said. “I’m going to ask you a list of questions, and you just have to answer honestly.” She must have realized that she was setting herself up by telling me to answer honestly. I tend to be verbose when people ask me to talk about myself; some would even say exhausting. I have no filter to limit my discourse to relevant things, and that puts people off. When I am invited to speak about myself, often what comes forth is the verbal equivalent of a volcanic eruption, spewing molten mind magma in every direction.

“I mean, you don’t have to deliberate each question,” she said, backpedaling. “I don’t need big, long answers, just honest ones.”

“Got it.”

She began: “Do you tend to get so absorbed by your special interests that you forget or ignore everything else? Just answer yes, no, or sometimes.”

“Special interests?”

“You know,” she said, “things like practicing your saxophone for four hours a day, or when you wrote scenes at the Second City and I hardly ever saw you . . .”

“Oh, well, sure,” I said. We both laughed. “I mean, doesn’t everybody get into stuff?”

“No,” she replied, marking down my answer. “Many people can do something they enjoy and not let it consume their whole life so they forget to pay bills, or put on shoes, or check in on their family from time to time.”

“Well. That’s their problem if they don’t have the intellectual capacity to engage constructively with an activity.”

“Next one: Is your sense of humor different from the mainstream or considered odd?”

I reflected back on the moment thirty seconds earlier, when I had cracked myself up by throwing my head back and bellowing what would be for most people a forgettable line from a Mel Brooks movie. Then I recalled going to a Victoria’s Secret store fifteen years earlier with my friend Greg and convincing the salesclerk that my girlfriend was shaped exactly like me, just so that I could quickly try on some lingerie against store policy (apparently) and give Greg a good laugh. That joke had been a success. But then I remembered the time in junior high when I glued a rubber chicken head to a T-shirt and wrote LET’S GET SERIOUS across the chest in permanent marker, only to be told at school that I’d have to wear something more appropriate. That time nobody had laughed. Finally, I recalled going to dinner with a customer a year earlier and taking a series of dirty jokes so far that he abruptly stopped laughing and asked what was wrong with me.

“Put me down for a yes,” I concluded.

“Do you often talk about your special interests whether others seem interested or not?” she asked. Her smile was answer enough, and I assumed that, like me, she was thinking of all the times in which I’d waxed lyrical about having perfected the art of using public toilets.

“Yes.” What else is there to talk about?

On and on it went, for over 150 questions.

“Do you take an interest in, and remember, details that others do not seem to notice? Do you notice patterns in things all the time? Do you need periods of contemplation?” All emphatically answered yes, with a follow-up, “This is fun!”

“Do you tend to get so stuck on details that you miss the overall picture? Do you get very tired after socializing and need to regenerate alone? Do people comment on your unusual mannerisms and habits?” Absolutely!

I found the questions rather amusing until we came to a section so personally revealing that it pulled the air from my lungs and made me forget how to blink.

“Does it feel vitally important to be left undisturbed when focusing on your special interests?” she asked. “Vitally is the key here.”

“Yes. You know how—”

“I know,” Kristen said, interrupting. “Before doing something or going somewhere, do you need to have a picture in your mind of what’s going to happen so as to be able to prepare yourself mentally first?”

This question seems rather insightful. “O-oh my God,” I stammered. “Yeah, that’s totally me.”

“Do you prefer to wear the same clothes and eat the same food every day? Do you become intensely frustrated if an activity that is important to you gets interrupted? Do you have strong attachments to certain favorite objects?”

“Those are all yes.”

“I know. Do you have certain routines which you need to follow? Do you get frustrated if you can’t sit on your favorite seat?”

“I literally have ended friendships over the seat thing. In high school—”

“Do you feel tortured by clothes tags, clothes that are too tight or are made in the ‘wrong’ material? Do you tend to shut down or have a meltdown when stressed or overwhelmed?”

All yes. But I was too stunned to answer aloud.

“How about, do people think you are aloof and distant? Do you often feel out of sync with others? In conversations, do you need extra time to carefully think out your reply, so that there may be a pause before you answer? Have you had the feeling of playing a game, pretending to be like people around you?”

I had chills. Actually, my skin was on fire. Actually, it was both.

“What is this?” I asked.

“Just keep answering honestly.” Kristen patted my leg reassuringly. “You’ll find out when we’re done.”

One by one, the questions described everything I already knew about myself—everything that I had always felt made me unique, beautiful, yet removed from other people. Folding my arms tight, I began to cry, which surprised both of us.

Kristen asked if I was all right, and I said that I was, so we continued. Another batch of questions brought back the laughter. In fact, most of the questions from that point forward were rather potent, evoking one strong emotion or another, though there were a few that seemed odd and out of place, such as “Do you sometimes have an urge to jump over things?” and “Have you been fascinated by making traps?” (Admittedly, it sucked a little to hear myself answering yes to both of those.)

We finished the quiz, and Kristen took a moment to gaze at me before asking, “What do you think?”

“I think that was a very telling list of questions,” I said. “Did you write those?”

She explained that she had stumbled upon the questionnaire while searching online for Asperger’s evaluation resources, though, notably, she offered little explanation as to why she had been looking for those resources. I had to assume that it wasn’t strictly for her job.

I felt like I was free-falling. “Okay,” I said.

“Ready to find out what it says?”

“Sure,” I said, though I was anything but.

Kristen clicked the mouse and my score flashed onto the screen: 155 out of a possible 200.

“One fifty-five?” I asked. “What is that? Is that a lot?”

“That’s a whole lotta Asperger’s,” she said, nodding.

“Are you serious?”

“That’s what it says.”

“I have Asperger’s? I have autism?! I mean . . . holy shit! Right?”

“Dave, you don’t have autism. You don’t even officially have an Asperger’s diagnosis. This is just a self-quiz and I’m not a doctor, but I think you may have Asperger syndrome. That’s why I wanted you to take this quiz. Based on your score, you’d probably receive the diagnosis if a doctor gave you a formal evaluation.”

I repeated myself: “Holy shit!”

At that point, all I knew about Asperger syndrome was what I’d heard from Kristen over the years. I understood that it was an autism spectrum condition and that those with Asperger’s had a difficult time engaging with others socially. I knew a few people with Asperger syndrome—diagnosed children and adults—and they seemed to function at different levels; some had obvious telltale behaviors while others could have been written off as shy or odd. I also understood that it could easily be misdiagnosed.

Wanting to know if the online quiz was a reliable weather vane, I asked Kristen—who is perhaps the most un-Asperger’s person that I know—to evaluate herself. She agreed, and scored an eight.

A few minutes passed as I sat on my hands, rocking back and forth, trying to process what I had just learned. Kristen sat patiently, keeping her eyes trained on me, waiting for my reaction. I was not upset. I was not conflicted. The knowledge felt amazing. It was cathartic. And it made perfect sense. Of course! Here were answers, handed to me so easily, to almost every difficult question I’d had since childhood: Why is it so hard for me to engage with people? Why do I seem to perceive and process things so differently from everyone else? Why do the sounds and phrases that play in a continuous loop in my head seem louder and command more attention than the actual world around me? In other words, why am I different? Oh my God, I have Asperger’s!

While someone else might question why his wife would sit him down and informally evaluate him for Asperger syndrome—in her pajamas, no less—at no point during that evening in Kristen’s office did I wonder about it. For one thing, there are certain orders and tasks that I simply don’t dispute; I just follow commands and generally do whatever people tell me to. But there’s no particular consistency to this, which is strange. Frequent requests from Kristen such as “Please remember to run the dishwasher tonight” don’t have much of an effect. But if I walked into a grocery store and someone grabbed my elbow and asked me to put on a hot dog costume, two minutes later I’d be standing there, a six-foot wiener in a neoprene bun, wondering how long I was supposed to keep it on.

What I found most remarkable about that evening—besides the part where I found out that I have Asperger syndrome—was that Kristen and I had shared some good hours together for the first time in months. There was laughter and insight and deep discussion. There was warmth and affection and unmistakable love—I could see it in her eyes, feel it in our closeness. Though we had been married only five years, such moments had become painfully rare. We both knew that our marriage had fallen apart, that our mutual feelings of helplessness and disappointment had pushed aside the fun and happiness we once shared, and more than once we found ourselves wondering if a separation was the only way out. Of course it wasn’t gloom and doom all the time, but I couldn’t deny the fact that we were estranged. That was not something we had ever envisioned happening to our relationship.

But once I learned that I have Asperger syndrome, the fact that we’d had these serious marital problems seemed less surprising. Asperger syndrome can manifest itself in behaviors that are inherently relationship defeating. It’s tricky being married to me, though neither Kristen nor I could have predicted that. To the casual neurotypical observer (neurotypical refers to people with typically functioning brains, i.e., people without autism), I may seem relatively normal. Cognitive resources and language skills often develop normally in people with Asperger syndrome, which means that in many situations I could probably pass myself off as neurotypical, were it not for four distinguishing characteristics of my disorder: persistent, intense preoccupations; unusual rituals and behaviors; impaired social-reasoning abilities; and clinical-strength egocentricity. All of which I have to an almost comically high degree. But I also have the ability to mask these effects under the right circumstances, like when I want someone to hire me or fall in love with me.

Looking back, I suppose a diagnosis was inevitable. A casual girlfriend might have dismissed my compulsion to arrange balls of shredded napkin into symmetrical shapes as being idiosyncratic or even artistic. But Kristen had been living with me—observing me for years in my natural habitat—and had become increasingly skilled in assessing autism spectrum conditions in her job as a speech therapist. While it is technically inaccurate to say that she diagnosed me (that wouldn’t have been possible or ethical, as she’s not a doctor), as far as I was concerned, I had received a diagnosis that evening. I went to bed 100 percent convinced that I had Asperger syndrome. I later received a formal Asperger’s diagnosis from a doctor, but that exercise hardly seemed necessary. Given my behaviors, it would have been just as easy to diagnose a nosebleed.

One of my most obvious symptoms is the way I handle myself in unexpected social interactions. Especially conversations, which involve many subtle rules. My problem is that I can’t seem to learn and apply the rules properly, though not for lack of trying. One is simply supposed to know the right way to respond to people or initiate conversations, but my attempts rarely pass muster. And due to my intense preoccupations with certain things, I have a tendency to discuss very strange topics at length, oblivious to the listener’s level of interest. A typical conversation might go something like this:

“How ’bout those Bears, Dave?” a colleague will ask.

“I don’t really follow sports, so I decline to form an opinion other than that I like their uniforms. It’s funny you mention bears because last night I was reading about grizzly bears, which are my favorite kind of bear, and I learned something rather unsettling about their mating habits.”

“Never mind.”

My responses confound people, I’m garrulous about all the wrong things, my speech is awkward, and then there’s also my not-at-all-charming delay in processing, which makes for disjointed conversation and missed social cues. Conversations either persist much longer than either party would like them to (“And here’s another thing that fascinates me about sewing machines . . .”), or they end too quickly (“You did hear correctly, we had a baby yesterday and it wasn’t without its complications. See you later”). Even if I manage to deliver my point, it’s usually somewhat irrelevant. (“So I guess what I’m trying to say about the Civil War is, how about the beards on those soldiers, huh? Where’s everybody going?”)

Over the years, I have learned some ways to compensate. When I know ahead of time who I’ll encounter in a particular situation, I can prepare. I have a strong tendency to assume characters—versions of myself that are optimized for the social environment at hand. Conversations must be scripted, facial expressions rehearsed, personalities summoned. This strategy has enabled me to succeed at work and in school and to do well enough socially. If I’m with conservative work colleagues, I’m reserved and willing to discuss Christianity and handgun rights. Neighbors enjoy a lawn-care enthusiast and classic-rock fan when I arrive at the block party, and Kristen’s relatives are always excited to see the gregarious, supportive man who values a respectful handshake. Whatever the occasion, and whichever corresponding persona I choose to wear for it, pulling off a successful social exchange is a lot of work. It’s exhausting. I don’t know how neurotypicals do it, let alone how they look forward to it.

Under the right conditions, I do enjoy going out with friends. We’ve already established common ground and I know what they expect from me. I get high from making people laugh, from performing. Goofing around with my buddies is still tremendously hard work requiring much preparation, but at least there’s a payoff: laughter. When I am on, and I’m with the right people, I am killing and full of deranged brilliance (I like to think). A pita may be swiped from someone’s plate and used as a potty-mouthed talking vagina, or I may demonstrate what I believe would be a controversial but effective new wiping technique for the bathroom. They laugh, go home, and wake up the next morning with real-world problems on their minds. I go home to review my performance. Was the talking pita vagina too potty-mouthed? Did the elderly couple a few tables over think I was boorish? How might I incorporate beating off into the bit about folk musicians? My head spins as it hits the pillow.

The social aspect, however, is only one piece of the Asperger’s puzzle. Sensory issues present another problem for me. As humans, we learn about our world through sensory stimulation. But for me, certain sensations become so overwhelming that I lose control of myself. While most people can go about their business oblivious to their partially untucked shirts and itchy sweater collars, I suffer major emotional tailspins over something as supposedly minor as pilly jean pockets. On many occasions, I’ve had to excuse myself from meetings at work to duck into the men’s room, take off my clothes, and completely redress myself because my underwear has bunched up, or my socks have twisted around my shins, or, heaven forbid, my shirt has static buildup. My solution is to buy several identical garments that feel all right against my skin, then wear them over and over until they fall apart. Take away the black jacket (those sleeves would drive me mental), and I’m like the Michael Kors of the Asperger’s community.

Of course, sensory issues and clumsy social exchanges don’t ruin marriages. What brought my marriage to its knees were my God-given egocentricity and inability to cope with situations and circumstances beyond my control. Put the two qualities together, and you’re left with something that looks like a combination of pathological closed-mindedness and an obsessive-compulsive disorder. OCD might not take down a marriage, but I’m certain that pathological closed-mindedness isn’t one of the top qualities a person would look for in a spouse.

Everybody likes to have things in order, and everybody likes things to go according to plan. But because of the way my brain developed, I need things to be in order, and I need things to go as planned. If they don’t, I come unglued. If left unchecked, my reactions resemble the tantrums my two-year-old would throw whenever someone would disturb his meticulous line of toy train cars. My inability to cope partially explains my horrible flash temper. If the grocery store is out of my preferred hamburger buns, for example, three hours later it will result in a nuclear reaction of cynicism and anger. The disruption of my routine is so upsetting that I can’t—not won’t, can’t—contain myself, and everyone around me sees the unpleasant effects. I’ve been told a million times to “get over it,” but I can’t. My brain won’t let me. Just as I can’t seem to prevent the regrettable outbursts that usually follow.

My preoccupations or obsessions often play a big part in this. To avoid meltdowns, I indulge certain obsessions, often at the expense of being on time for things. I must eat eggs and cereal for breakfast, for example. If we are out of cereal, then I will go to the grocery store and buy some, even if people are waiting for me at work. I may arrive at the office a couple hours late, but I’m satisfied and ready to focus on my assignments.

Fortunately, I have an assortment of routines that are very calming when properly executed. If my intense preoccupations resemble Obsession, then my calming rituals would be like Obsession’s diaper-wearing pet monkey, Compulsion. I spend my day lining certain items up just so, tapping or lightly touching objects in a particular way, and gazing at my own penmanship. The compulsive behaviors are really quite small and limited, and with the exception of my nightly circling the house, having to correctly perform a mental ritual before exiting certain rooms, flicking light switches on and off, and repeatedly opening and closing doors, they’re really not all that intrusive. They tend to become more pronounced when I’m anxious about something, but all things considered, I’ve got it easy.

Kristen, on the other hand, doesn’t have it so easy. She’s married to all of this. Her frustration is inevitable, no matter how much she loves me. But that’s how it goes, especially in neurologically mixed marriages such as mine. Were I just another one of the kids she works with, Kristen wouldn’t be frustrated by me. But I’m her husband.

Kristen and I had been friends since high school, had fallen in love after college, and had gotten married shortly thereafter. During the years we dated, I was on my best behavior. Don’t talk about semiconductors all night, I’d remind myself. Remember to keep the conversation moving and focused on things she likes, such as Vince Vaughn and clothes. If she doesn’t feel like eating hamburgers for dinner, just be okay with it and don’t flip out.

When I slipped, she seemed to find my eccentricity endearing. I remember her laughter upon discovering dozens of pictures I had taken of myself to see what I might look like to other people at any given moment: me watching TV; me about to sneeze; me on the toilet, looking pensive.

She loved the story of how I took an emergency leave from work to boil my glasses after they had fallen from my shirt pocket in a men’s room stall. She found it pitifully charming when I would stand alone at parties, kind of dancing, or follow her from room to room, unable to engage with anyone else.

It was all so charming until we got married and there was nowhere for Hyde to hide. I became incapable of concealing the truly damaging behaviors I’d managed to stave off for so long—selfishness, meltdowns, emotional detachment. She never saw it coming. With people I like and for short periods of time, I’ve always been able to sustain a wonderful version of myself. With enough effort, I can even pull off enchanting. (Prince Charming is one of my most highly developed characters.) This was how I won Kristen over when we began dating. Because I was able to keep up appearances for a long while, it came as a major surprise to both of us when, a few months into our marriage, she started seeing through the ever-widening cracks in the facade I’d created, revealing the person I’d been since childhood, someone who wasn’t programmed to be an ideal, supportive partner.

I never meant to pull a fast one or to deceive Kristen in any way. I was profoundly in love with her. Like anyone, I wanted to put my best self out there, and thanks to the intoxicating effects of new love, I genuinely believed that I would forever be that best version of myself. But not long after we were married, my handful of endearing quirks began to multiply, making me, as a husband, exponentially more annoying and harder to deal with. Quirks are like sneezes or energetic puppies—one or two aren’t so bad, but try dealing with ten thousand of them. Eventually, Kristen’s life became flooded with my neuroses, and she found herself wondering who in the hell she’d married.

She was, for example, understanding when I first insisted that all groceries be purchased from the Jewel-Osco grocery store, but when I started demanding they be purchased from the Jewel-Osco grocery store two towns over, rather than from the one right by our house, she protested. “‘Because that one has a better vibe’ is not reason enough,” she said, but I had no other way to explain why the routine of going to that store was so critical. It just was.

When we were stuck in a traffic jam following a multiple-vehicle pileup, she listened for an hour as I speculated on the questionable driving habits of the victims before turning up the volume on the radio and saying to me, “People are probably dead. Can you please try and have an ounce of compassion?”

And annoyed by my constant questioning about how long the Thanksgiving feast at Aunt Deb’s might last she snapped, “Why does it matter how long the dinner will be? I have no clue. None. Get over it.”

Ashamed by my apparent insanity, by a personality I couldn’t seem to control, I slowly withdrew from Kristen over the first few years of our marriage. Confused and disappointed, she allowed herself to do the same. I resigned myself to the belief that we were fundamentally incompatible and that this was to blame for our resentment toward each other, the terrible distance between us, the way she was cold to me but would spring to life around everyone else. For years we just didn’t know how to fix it. This wasn’t the life I had imagined living, and so I felt all along that our marriage had failed me. It had never occurred to me to step back and look at the situation differently—to concede that perhaps our marriage had failed because I had failed our marriage.

My diagnosis changed everything for us. The impact of the knowledge was deep and immediate. “This explains so much,” we kept saying. Of course, when I said it, the implication was that the diagnosis explained so much about me and my life. Now, looking back, I understand that when Kristen said it she had meant “This explains so much about us.” (How’s that for egocentricity?) The instant my score was calculated my alienating, baffling behaviors were transformed into well-documented symptoms of a known disorder—they no longer seemed malicious and unexplainable. Kristen understood that the damaging behaviors were not my fault, exactly, and was able to see me in a new light. Her resentment vanished; I was forgiven.

Kristen went to bed that evening feeling better than she had in years, she told me. After she went upstairs I stayed in her office, in front of her computer. I decided to research autism spectrum conditions, knowing that I would not be able to shut off my brain and go to sleep that night. Every website I visited, every personal account I read, every clinical paper I skimmed was another helpful resource, more good news for me.

At some point, in the hours that I spent absorbed in research and raw self-discovery, something occurred to me: I process things differently from Kristen, I’m as socially functional as a tuba, I don’t look beyond my own needs and my own interests, I haven’t been talking to her, and I behave very strangely. No wonder our marriage sucks right now. I think this Asperger syndrome may just be what’s destroying our marriage! I know, I know—great detective work. But with that discovery, I felt as though I’d been reborn. The reason we struggled for so long to find solutions to the problems in our marriage was that we hadn’t understood their causes. Identifying the source and knowing that it affected millions of other people made for a very short leap to the conclusion that I could finally do something about it. We’re screwed suddenly became We’re saved!

It’s amazing how swiftly a spot diagnosis can catalyze change. As a teenager, I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (ADD)—first unofficially, by my mom, and then officially by a doctor. I’ve been taking Ritalin or something like it ever since, and it works. The medication helps me to process information, focus my thoughts, and keep myself organized at a functional level that I can’t achieve on my own. But there is no silver bullet that will eliminate all the difficulties that come with Asperger’s. If there had been a single pill that would help me to put the needs of others before my own, to rid my life of meltdowns and control issues, and to help me to be a highly sociable person, then I would have been mighty tempted to take it, if only to stop annoying everyone around me. But I couldn’t take a pill that would accomplish all of that—it doesn’t exist—so I decided to take initiative.

Armed with knowledge and new self-awareness, I could start looking every day for ways to manage the behaviors that had been wreaking havoc on our marriage. Address the causes and the symptoms will vanish. I wasn’t interested in a complete personality overhaul; I just wanted to become more in control of myself.

“I think I can fix our marriage,” I said to Kristen the following morning. “I’m basically the one who destroyed it, and now that I know what my behaviors are doing to us, I can start working on ways to improve myself.”

“Dave, that’s awesome, but it’s not all because of you,” she said. “You didn’t destroy our marriage, and I hope you know that. I’d say there’s a lot that we both need to work on in our relationship, and we can do it together.”

“Sounds good to me.” I had no idea what she intended to sort out from her side; I was so focused on myself that I didn’t even bother to ask.

We also agreed that there was a lot about me that we hoped would never change. The harmless little quirks that, in Kristen’s words, “made me Dave”: achieving perfectly consistent spacing between all ten fingers, getting carried away with an internal recitation of a phrase to the point where it blurts from my lips (“Heyoooo!”), repeatedly snapping pictures of myself. These were the things we wanted to keep. However, doing those things while she and the kids wait outside in the car, late for our son’s baptism, well, that’s exactly the sort of thing I was hoping to overcome.

My hope was that by transforming myself, I would bring about some transformation in our marriage. Transforming myself would mean changing my behaviors, and I knew it wouldn’t be simple or easy. If it were, I probably would have done it long ago.

Most people intuitively know how to function and interact with people—they don’t need to learn it by rote. I do. I was certain that with enough discipline and hard work I could learn to improve my behaviors and become more adaptable. While my brain is not wired for social intuition, I was factory-programmed to observe, analyze, and mimic the world around me. I had managed to go through school, get a good job, make friends, and marry—years of observation, processing, and trial and error had gotten me this far. And my obsessive tendencies mean that when I want to accomplish something I attack it with zeal. With my marriage in dire straits, I decided that even if I needed to make flash cards about certain behaviors and staple them to my face to make them become second nature, I was willing to do it.

Kristen didn’t know it, but that was what her life was about to become—her husband, with the best of intentions, stapling flash cards to his face. Okay, not to his face. And there were no staples involved. But flash cards? Definitely. Many people leave reminder notes for themselves: Pick up milk and shampoo, or Dinner with the Hargroves at 6:00. My notes read: Respect the needs of others, and Do not laugh during visitation tonight, and Do not EVER suggest that Kristen doesn’t seem to enjoy spending time with our kids.

Opportunity for change was everywhere, I noticed. When I thought of something I wanted to address, or when I learned something in an argument with Kristen, I would write it down. Don’t change the radio station when she’s singing along. When she’s on the phone, don’t force yourself into the conversation. Don’t sneak up on her. I wrote these little gems everywhere: on loose-leaf paper, in my notebooks and journals, on my computer and phone. One particularly intense series of realizations, which ultimately led to remarkable breakthroughs in our relationship, was recorded on an envelope that I kept in the pocket of my car door.

In order to keep up with the rapid pace of inspiration, I started keeping a journal—the Journal of Best Practices. This wasn’t some huge, leather-bound diary that I kept under my pillow, as one might expect. That wouldn’t have been practical, since there was no telling where I’d be when my feverish rumination would cough up a new best practice. Rather, the Journal of Best Practices was my collection of notes. I could have called it my Nightstand Drawer of Best Practices, since that’s where most of the scraps of paper, envelopes, and actual journals ended up—but what kind of wacko keeps a Nightstand Drawer of Best Practices?

Collectively, the entries in my Journal of Best Practices would become my guiding principles. Some of them would stick. Others would not. Some would be laughably obvious (Don’t hog all the crab rangoon), and certain others would be revealed only after many painful scenes. Even so, the hardest work would lie not in formulating the Best Practices but in implementing them. But with our happiness at stake, that’s what I’d learn to do.

© 2012 David Finch