What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Copyright information

Excerpts from Reel 1: The Theater

Genesis of the Theater

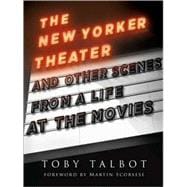

“What kind of work is running a movie house?” my father-in-law asked. Who knew? Not us, until we opened the New Yorker. It ran through the sixties and early seventies: a golden age in cinema, turbulent in politics—French New Wave on our screen,’68 uprisings at Columbia University. An Upper West Side hub became, as Bernardo Bertolucci dubbed it, “a kind of wild cinema university, like Henri Langlois’s Cinémathèque in Paris.” We were young film buffs, learning as we went. Not knowing where we were going. The theater is gone, but its marquee still glimmers in my mind. As we shaped it, it shaped us. Movies, moviegoers, our own lives unspooled on one ongoing reel. The New Yorker became our anchor, where time and place converged. I thought it would go on forever.

How the Theater Got Its Name

In 1934 Broadway had eighteen movie theaters between 59th to 110th Street, only ten then functioning: the Regency at 67th Street, the Loews 83rd, the Adelphi (now the Yorktown) between 88th and 89th, the Symphony and the Thalia at 95th, the Riverside and the Riviera on 96th, the Midtown at 99th, the Edison at 103rd, and the Olympia at 107th. Most were “flea pits” or “toilets” in movie house jargon, with lumpy seats, poor sight lines, musty odors, and scuttering roaches. Former picture palaces—relics of palmier days—had been converted into TV studios and supermarkets. The Yorktown marquee perennially promised TWO BIG HITS irrespective of what was playing, while the Red Apple to the right announced FRYERS AND BROILERS 39 CENTS PER POUND, and Joe Rosen’s Butcher Shop to the left brandished strings of kosher salamis on lustful hooks.

But by the early sixties, the Upper West Side began undergoing change. Young couples in the arts and professions were moving into old brownstones and apartment buildings. It was the only place in Manhattan where one could find a large, roomy flat at an affordable rental. Nobody then was thinking Harlem, Williamsburg, Staten Island or, God forbid, New Jersey. This was a harbinger of other unfashionable neighborhoods getting developed: Soho, Noho, Chelsea, Tribeca, Park Slope, Boerum Hill and, yes, Harlem and Williamsburg.

The Upper West Side, some two square densely populated miles, was definitely under-screened. And Dan came up with an idea: he convinced Henry to allow him to experiment a while, converting the Yorktown into a revival house, Dan himself managing it. Well, Henry was not born yesterday: a practical fellow, he was not given to throwing money down the drain, no less on an “art house.” Dan’s salary was to be $125 a week, plus one-third of the profits. If the theater failed to turn a profit after the year was up, Henry figured, that spot could always be added to his Hispanic chain.

On March 7, 1960, Rosenberg’s office issued a release: “Brandt’s Yorktown Theater (900 seats) has just been purchased by Arjay Enterprises, Inc.”

Oh Henry! We were ready to roll. Four neon letters salvaged from the Yorktown morphed into the New Yorker.

How did the theater come by its name? In the early thirties, my Uncle Harry, ingenious and dapper, a sometime bootlegger in the heyday of Prohibition and a fellow with chrain (or “horseradish” as the Yiddish expression goes), who drove a cobalt blue Buick and smoked Havana cigars ignited by a silver lighter matching the pattern of his wife Rosie’s tenth anniversary compact, decided under counsel of her cardiologist to move to Miami’s beneficent climate. Though its coast was sheer swampland, it occurred to Uncle Harry that what its beaches needed was a hotel. Surely others, aside from his family, would be migrating south to escape the cold. Uncle Harry was a quick mover. Within a year, mangrove marshes got drained and the New Yorker Hotel rose on 1415 Collins Avenue. One of the earliest hotels in Miami Beach, it was a proud Art Deco structure pictured on the postcards sent us by Uncle Harry, Aunt Rose, and cousins Moe and Yetta. Sybaritic South Beach was far in the wings. As a parting gift, Tante Rosie bequeathed me her compact, an anticipatory gift of adulthood for an eight-year-old, and I was heartbroken when it got lost in the Málaga airport in 1959. But in tribute to the gods of Enterprise and the Recycling of Letters, we named our offspring the New Yorker.

An Art Deco relief of Diana the Huntress and her hound hung above its marquee. At night, yellow and green lights—sometimes a letter missing—lit up the block and on a rainy day painted the sidewalk. You handed the cashier $1.25, swung past the turnstile, entered a mirrored lobby, and turned to ogle the overhead banner of black-and-white photos of Greta Garbo, Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Peter Lorre, and company. On August 10, 1960, when Gloria Swanson in white ermine, white limousine, and black chauffeur showed up to see Sunset Boulevard—about a star dreaming of a comeback for millions who’d never forgiven her for deserting the screen—she lit up on finding herself in that stellar company and promptly checked her aging self on the mirrored wall, still angling for the best profile.

Opening ProgramsOur first show on March 17, 1960, was Henry V, starring Laurence Olivier and a chorus advising its audience “to eke out our performance with your mind.” What better counsel for the rapture of art? Co-featured was The Red Balloon, a fantasy about a Parisian boy’s friendship with a red balloon, and then soaring into the heavens. The program ran for three weeks. As people lined up, we too were soaring! Shortly before noon, we stood in the empty theater, hall dark and quiet, seats unoccupied, screen blank, an air of stillness pervading an Edward Hopper kind of space. Moviegoers began drifting in, seats filling. The screen came alive.

That initial Friday evening of operation, Henry V and The Red Balloon drew over two thousand moviegoers, and within three months audiences came flocking, not just from our neighborhood but, as guest books revealed, from the five boroughs, New Jersey, and Connecticut. The two-week total for that first twin bill was over $10,000. Soon theaters around the country were copying our programs.

Item—June 1960: by New York Post critic Archer Winsten: “The New Yorker is a sizeable theater and can hold many people comfortably. At present it seems to be by far the most exciting film theater in town, not just for what it shows but for the departures and promise of its future. Obviously, it’s the only theater with new and fresh ideas.”

“Imagine the courage it took to launch a movie house,” critic Phillip Lopate remarked in 2008. “Dan had no illusions of being gifted at business,” I replied, “but somehow he managed to develop mature business judgment.” One learns by doing, said John Dewey. And, as Nathaniel Hawthorne declared, unemployment may lead to the next step. Hawthorne himself, “decapitated” from a three-year post as Customs Surveyor when his party lost power, said that “the moment when a head drops off is seldom, or never, I am inclined to think, precisely the most agreeable of his life. Nevertheless, like the greater part of our misfortune, even serious contingency brings the remedy and consolation with it, if the sufferer will but make the best, rather than the worst of the accident which has befallen him.” The life of the New Yorker lay like a dream before us.

“Get yourself some real work. Study to be a pharmacist,” Dan’s father persisted—doctor, dentist, or lawyer not prescribed. For a son hooked on Proust, Joyce, Kafka, Rossellini, and Fellini, professional Dog Walker was equally unlikely. Make a living is what he meant. Pursue a profession, or some useful trade, where not apt to be fired. Nor were writer, critic, or editor on Dad’s list. Where had his own studies in philosophy and language at Cracow University landed him? It was the Depression. You did what you had to do. He became a textile jobber; he became a worrier, mindful of the cost of a loaf of bread. Why mention that Dan, while attending New York University, had moonlighted as a soda jerk and taxi driver just to hole up in spare time with the Partisan and Sewanee Reviews? Why mention that Carl Theodor Dreyer could pursue his art through income derived from managing the Dagmar Movie Theater in Copenhagen? Why mention that James Joyce in 1919 came up with the brainstorm of opening a movie house in Ireland and, aided by some Trieste businessmen, transformed a Dublin building—the numbers went south, the scheme was a flop, and the whole thing shut down that very year. Anyhow, who in the world when asked as a kid what he wants to be when he grows up pipes up with exhibitor? Two years later, in 1962, we purchased the lease from Rosenberg, assisted by my parents, who withdrew their little nest egg from the bank, as did our parsimonious friend, the writer Chandler Brossard, who withdrew his last $6,000, without examining the “financials.”

Following that first three-week program of Henry V and The Red Balloon, the second bill was Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Marcel Pagnol’s Harvest: austerity and abundance. Next came Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons and Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie’s Pull My Daisy, a quirky Beat Generation riff shot in Leslie’s loft in 1959 and narrated by Jack Kerouac of the mellifluous voice: odd film couples from the word “Go”! Ginsberg’s Howl and Kaddish, Kerouac’s On the Road, and the poems of Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti had been published by then. On September 5, 1957, Gilbert Millstein, reviewing On the Road in the New York Times, called it ”the most beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance yet made by the generation Kerouac himself named years ago as ‘beat.’ ” But in 1958, when Millstein brought two Columbia buddies in checked flannel shirts to our living room, who could have foreseen what Ginsberg and Kerouac had in the works? Pull My Daisy, an ode to the Beat Generation, had a rich cast including Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Richard Bellamy, Alice Neel, and Larry Rivers. The twenty-nine beatific minutes at a surreal dinner party with a bishop and a working-class family were, well, fresh as a daisy. Even so, one customer wanted his money back. He thought we were showing Please Don’ t Eat the Daisies. “You wouldn’t catch me going in there with a ten-foot pole,” Dan overheard one passerby say to another. “They play such crazy shows. But such lines at the box office!” The program sold over 7,300 tickets during its two-week run and had people cheering from their seats.

As a revival house, we showed American movies along with others that had English subtitles at the bottom of the screen, the kind of films our kids’ friends didn’t care to see, even without paying. To this day I find it exhilarating to slip into our movie theater for free—and without waiting “on line”! On Monday the Andrew Sisters might be crooning “Don’t sit under the apple tree with anyone else but me,” while on Tuesday Emil Jannings would weep for his unattainable Blue Angel, and on Wednesday hyper Harpo, boozy W. C. Fields, or deadpan Buster Keaton might be doing their stuff. I, onetime acrobat and tap dancer, was smitten by Keaton’s rubber-band stunts, and loved standing in back of the theater when we played a comedy, listening to the laughter—a crowd’s laughter more restorative than attending church or temple. “Make ’em laugh, make ’em laugh,” enjoins Donald O’Connor in Singin’ in the Rain. And in Preston Sturges’s comedy, Sullivan’ s Travels, a chain-gang audience in a dirt-poor rural African-American church escapes their confinement by roaring over the antics of Mickey Mouse and Pluto. I could always locate Dan by his bursts of laughter as he sat in the audience watching W. C. Fields.

Our audiences were viewing Hollywood movies as art, not just popular entertainment. Screwball comedies, gangster flicks, musicals, and westerns—films of the ’30s and ’40s that we’d gorged on as kids—shared our silver screen with Murnau, Eisenstein, Griffith, von Sternberg, Lubitsch, and Renoir. The theater became a cocoon for young people getting schooled in film. “That’s where I found my education,” says Peter Bogdanovich. That’s where Vittorio De Sica’s Shoeshine got paired with Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory with Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve with John Huston’s Treasure of Sierra Madre, and Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped with Jacques Becker’s Casque d ’ Or. The theater had a policy of no policy. We thought of it as our living room, playing movies we wanted to see. For two days and nights, ignoring Hollywood censors, the Maltese Falcon bedded with Hedy Lamarr—nostrils flaring and breasts quivering—and no one fainted! Unlike the “thematic” programming of most exhibitors—two musicals, two westerns or two social films—ours was fragmented. Opposites attracted, and our audiences—including Morris Dickstein, then a young Columbia student—found that exhilarating.

Common wisdom holds that to start a new enterprise one must develop a business plan describing concept, felt need, competition, individuals involved, five years of financial projections, etcetera. We had none of those. Who knew what would happen in the next few months? It’s not like being pregnant for nine months. But who’s ever prepared for that? Who’s ever prepared for any new undertaking? Nothing is more hopeless than a scheme for merriment, declared Samuel Johnson. “Our aim at the New Yorker,” said Dan, “is to present films that won’t embarrass the eye or ear. If we make enough money to sustain the kind of programs we envision, fine, and if we get clobbered, maybe the next best thing is to go in for burlesque.&rdqu

In the first six months, films long unseen were shown: Buster Keaton’s The Playhouse and The Boat, Charlie Chaplin’s Easy Street, The Cure, and The Immigrant, Max Reinhardt’s Midsummer Night’ s Dream, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, and René Clément’s Forbidden Games.

What a moment in cinema! The three B’s: Buñuel, Bergman, Bresson (like Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms), all operating at full steam; with Fellini, Visconti, Pasolini, Godard, Truffaut, and Chabrol at our beckoning. That’s what movies are and how they’ll always be, we thought, awaiting the next with bated breath. Going to the movies in our own movie house was a fantasy come true: seeing the audience, being part of that audience, having created that audience.

In 1960 the New Yorker drew about seven hundred patrons on Friday nights and close to a thousand on Saturdays and Sundays. The theater grossed around $350,000 that year, which meant that we’d succeeded well enough financially to remain open: we had found an audience.

In the sixties, cinema and politics marched in tandem: post–Cold War, post–Joseph McCarthy, atomic bomb embedded in everyone’s psyche (Dan’s cousin built a fallout shelter on Long Island and a friend contemplated moving to Canada). The era witnessed three presidents with ambitious agendas and facing momentous events: John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier, Peace Corps, Cuban Missile Crisis, and ultimate assassination; Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution leading to the Vietnam War, and the pivotal Tet offensive, with Richard Milhous Nixon reaping the aftermath and putting his own spin on things. The upheavals of the spring and summer of 1968 saw Martin Luther King’s assassination in April, Robert F. Kennedy’s in June, racial rioting in American cities, and the disastrous Democratic convention in Chicago, with police intervention. It was an era of massive civil rights struggles and, overshadowing all, the Vietnam War. We staged antiwar demonstrations in Central Park and a candlelight march on Broadway. A World War II veteran marched on crutches; our four-year-old daughter sat atop Dan’s shoulders. “Keep her away from the flame,” I begged. The country was burning; we were killing our heroes—John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. Busloads of youths rode south for demonstrations and sit-ins while others rocked to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, read Dr. Timothy Leary, dropped acid, became flower children, joined counterculture communes. A neighbor invited us to a New Age weekend at Esalen in Big Sur, California, to take the baths and liberate our psyches. People guffawed at seditious Lenny Bruce, read Philip Roth’s Portnoy’ s Complaint (whose mamela surpassed all others), and witnessed on television the racial battles in Detroit, Watts, Haight-Ashbury, and Washington, D.C. On arriving one morning at Columbia University, three subway stops away, to teach Latin American literature in Hamilton Hall, I found the building occupied, graffiti scrawled on its walls. The student demonstration had begun. But the SDS—Students for a Democratic Society—declared our New Yorker a “liberated zone.”

I used to feel guilty about going to a screening first thing in the morning, while others hurried to office, factory, and school. What a way to start the day—grown-ups playing hookey. You enter the dark, only to emerge blinking an hour or so later into blinding glare, beeping horns, flesh-and-blood creatures bustling about. Now that was Reality—enough to give you the bends. But, said George Balanchine, non-reality is the real thing. And watching movies, nursing an infant in darkness, and greeting on-and-off-screen characters became ours. A merging of real and reel, actuality and illusion.

Down the aisle I’d glide, stealthy as a thief savoring loot in a prospective coffer, steps muffled by zigzag carpet lines as familiar now as the cracks on my bedroom ceiling. Darkness and theater aroma beckon, nymphs on the red velvet walls sway in their timeless dance, tiny exit lights glimmer like magic lanterns pinned against the dark. The screen billows in chaste whiteness—pre-movie shuffle of coats, handbags, and umbrellas; candy wrappers unfurl; glasses emerge as heads lean this way and that for the best sight line. Finally silence falls. Eyes roam the becalmed sea of a blank screen. Passengers await departure. House lights go off. Credits go on. We sail forth into dreams. I’m my 10-year-old tap dancer self in blue satin bra and skinny shorts with silver sequins à la Ginger Rogers in The Gay Divorcee. I’m Charlie Chaplin tucking into a boiled, scruffy shoe, carving it delicately like succulent chicken, twirling laces on my fork like spaghetti, and nibbling the nails of its soles like bones. I’m Katharine Hepburn sailing down river with Bogart in The African Queen, I’m the mother in Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, I’m Joan of Arc, I’m Nanook of the North, I’m King Kong! In Borges’ tale Nadie Hubo en El, Shakespeare is in search of Shakespeare.

The theater became an Animator—a cinema mecca, Jules Feiffer called it. One picture bestirred another, one moviegoer another. “There’s nothing out there to see!” some may grumble nowadays. “Oh yeah?” Jimmy Durante might say. Movies, a hundred years young, have a sturdy past—from Méliès’ magic lantern, the Lumière Brothers, F. W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, D. W. Griffith, Josef von Sternberg, to Orson Welles. Who can resist a retrospective of Roberto Rossellini, Jean Renoir, or Yasujiro Ozu? Or ignore the Taiwan or Korean cinema, or Zhang Yimou? Or thrill to discovering a new director from Senegal, Mexico, or Turkey? Who can resist sitting in a theater, sharing a frisson with others? Who can resist getting out of the house and getting out of oneself?

...

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Published by Columbia University Press and copyrighted © 2010 Columbia University Press. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. For more information, please e-mail or visit the permissions page on our Web site.