The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

“Do you recognise him?”

“I’m not sure.”

“He has the look of a murderer, has he not?”

“Do you think so?”

“Yes, I do. It’s his smile, Robert. Never trust a man who shows you his lower teeth when he smiles.”

“But the poor wretch is dead, Oscar.”

“The rule applies, nevertheless.”

“And this is just a waxwork.”

“But it was sculpted from life, Robert, or, at least, directly from the cadaver. It’s a point of honour with the Tussaud family, you know. They will have had access to the body within hours of the execution.”

It was midmorning on Christmas Eve, Wednesday, 24 December 1890, and with my friend Oscar Wilde, I was visiting the celebrated Chamber of Horrors at what was then London’s—England’s—the Empire’s—most popular public attraction: Madame Tussaud’s Baker Street Bazaar.

Oscar was at his most ebullient. As we toured the exhibits, peering through the flickering gaslight at the waxwork effigies of the more notorious murderers of recent years, my friend’s moonlike face shone with delight. His eyes sparkled. His large frame—he was more than six feet tall and, now thirty-six years of age, tending to corpulence—heaved with pleasure. Nothing amused Oscar Wilde so much as the wholly improbable. “ ’Tis the season to be jolly,” he chuckled softly, “and we are bent on horror, Robert.” He glanced at the multitude around us and beamed at me. “It is the anniversary of Our Lord’s nativity and all London, it seems, is making a pilgrimage to a shrine to child murder.”

Certainly, in its sixty-year history, the Baker Street Bazaar had never been busier than it was on that day. Thirty thousand people had stood in line to see Tussaud’s latest sensation: an exact reproduction of the sitting room in which, only nine weeks before, Mary Eleanor Pearcey had battered her lover’s wife and baby to death. Mrs. Pearcey had piled her hapless victims’ corpses onto the baby’s perambulator and dumped them on waste ground near her home in Kentish Town. John Tussaud spent two hundred pounds—the price of a small house—on acquiring the perambulator and other souvenirs of the murder, including the murderess’s bloodstained cardigan and the boiled sweet that the innocent baby was sucking on as he was killed. John Tussaud’s investment reaped a rich reward. In those days, entrance to the Baker Street Bazaar cost a shilling a head.

Oscar and I had not paid the price of admission, however. Nor had we queued to get in. We had gained access to Tussaud’s via the staff entrance in Marylebone Road as special guests of the management. We were due to meet up with our friend, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Doyle was a friend of Madame Tussaud’s great-grandson and heir, John Tussaud. Arthur had arranged the visit as a Christmas treat for Oscar and Oscar had arrived bearing a Christmas present for Arthur. The two men had only known each other for sixteen months, but they were firm friends. Their intimacy—their ease with one another—surprised me because, as personalities, they were so different. Oscar was Irish, an aesthete and a romantic. Oscar was flamboyant: he revelled in the outrageous. Arthur was Scottish, a provincial doctor and a pragmatist. Arthur was stolid: he respected the conventional. But both were writers of high ambition, with keen intellects and lively sensibilities, and both were fascinated by the vagaries of the human heart and the workings of the criminal mind.

Oscar was five years older than Arthur, and, in 1890, undoubtedly the better known. The pair had been introduced to one another by an American publisher, J. M. Stoddart, who, on the same evening, in August 1889, had commissioned a “mystery adventure” from each of them. For Stoddart, Doyle was persuaded to write his second Sherlock Holmes story and Oscar conjured up his novel of beauty and decay, The Picture of Dorian Gray. Doyle’s Holmes adventure, The Sign of Four, was well received and helped consolidate the young author’s growing reputation as a skilful spinner of satisfying yarns. In its way, Dorian Gray helped consolidate Oscar’s reputation, too. The book was denounced as immoral. The Athenaeum called it “unmanly, sickening, vicious.” The Daily Chronicle derided it as “a tale spawned from the leprous literature of the French Decadents—a gloating study of mental and physical corruption.” It was banned by the booksellers W. H. Smith.

Oscar envied Arthur his creation of Sherlock Holmes. Arthur envied Oscar his way with words. Arthur had no reservations about Dorian Gray. He considered the work subtle, honest, and artistically good. He respected Oscar both as a writer and as a gentleman. And, amusingly, he also reckoned that Oscar had the qualities essential in a private detective: “a retentive mind, an observant eye, and the ability to mix with all manner and conditions of men.” Arthur told Oscar that if ever he should write another Sherlock Holmes story he would invent an older brother for the great detective and base him on Oscar. “Do so, Arthur, please,” said Oscar. “Your stories will stand the test of time and I have immortal longings.”

Madame Tussaud’s, that Christmas Eve morning, was packed to overflowing, but even among the crowds and in the half-light of the Chamber of Horrors, Messrs. Doyle and Tussaud had no difficulty in finding us as we hovered between the reproduction of Mrs. Pearcey’s sitting room and the ghastly waxwork of the grinning murderer with the exposed teeth. Oscar was both the tallest man in the room and the most conspicuous. He was dressed for the season: his elaborate bow tie was holly red; his dandified frock coat was ivy green; and in his buttonhole he sported a substantial sprig of mistletoe.

“Merry Christmas, Oscar!” called out Conan Doyle, pushing his way through the throng towards us. “Season’s greetings, Robert.”

Doyle held out his right hand towards Oscar. Oscar ignored it and, passing the brown parcel containing Doyle’s intended Christmas present to me to carry, embraced the good doctor in a mighty bear hug. Oscar knew that this hug embarrassed Conan Doyle, but it was the way in which he always greeted his friend: Arthur’s handshake was almost unendurable. Doyle was not tall, but he was well built, sturdy, fit, and strong, and the vicelike grip of his hand was as forbidding as his fierce moustache. Conan Doyle’s dark, walruslike whiskers would have done credit to a Cossack general.

“I’m sorry I’m late,” said the young doctor, prising himself from Oscar’s warm embrace. “The train from Southsea was delayed. A body on the line. Most unfortunate.”

“Some people will do anything to avoid a family Christmas,” murmured Oscar.

Arthur sniffed and furrowed his brow disapprovingly. “May I present our host, Mr. John Tussaud?” he said, taking a step back to introduce us to his companion. Mr. Tussaud rose briefly onto his toes, nodding his head briskly towards each of us as he did so. With his drooping moustache and wire-framed spectacles, he looked more like a mild-mannered schoolmaster than a purveyor of horror to the masses.

“Thank you for your hospitality, sir,” said Oscar, with a gentle bow. “And congratulations on the show.” He looked about us at the crowds, two or three deep—men and women, gentlefolk and workers, children and babes in arms—trooping steadily past the exhibits, mostly in silence. “It is a triumph.”

John Tussaud flushed with pleasure and pushed his spectacles further up his nose.

Oscar went on: “I was particularly taken with the half-sucked sweet retrieved from the dead baby’s mouth.”

“Yes,” said Tussaud eagerly, “the sweet does seem to have caught everybody’s imagination. It’s raspberry flavoured, you know.”

“Good God, man,” exclaimed Conan Doyle. “Did you taste it?”

“Only briefly,” said Tussaud with a nervous laugh. “I felt I should. The visitors like as much detail as possible.”

“I understand completely,” said Oscar soothingly. “Your visitors need to know that what they’re witnessing is the genuine article. The more corroborative detail you can give them the better.”

Tussaud looked up at Oscar gratefully. “You understand, Mr. Wilde.”

Oscar smiled at John Tussaud and touched him on the shoulder. “I was telling my friend Sherard here that all your waxwork models are drawn from life—or death, as the case may be.”

“Absolutely,” replied Tussaud seriously. “We insist on it—wherever possible. With the murderers, of course, we’re very much in the hands of the authorities. Some prison governors let us in prior to the execution, so that we can make a model of the murderer while he’s still alive. Others won’t let us in at all—or only give us access to the murderer’s body after the execution has taken place. That’s not very satisfactory, to be candid.”

“Hanging distorts the features?” suggested Oscar.

“It can do, I’m afraid,” replied Tussaud, lowering his voice as a group of young ladies pressed past us. “From a waxwork modeller’s point of view,” he continued, sotto voce, “the ideal method of execution has to be the guillotine. My great-grandmother was so fortunate in that respect. The Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris sentenced sixteen thousand five hundred and ninety-four people to death, you know. The guillotine was invented to cope with the numbers.”

“You are a ‘details man,’ I can tell, sir,” said Oscar, smiling.

“I have the complete list,” murmured Tussaud. “All the names.”

“Your great-grandmother must have been spoilt for choice,” said Conan Doyle grimly.

“And run off her feet,” added the great-grandson. “Families wanted death masks of their loved ones. Those who were about to die wanted to be immortalised in wax. The demand was incredible—one head after another. We have the original guillotine here, you know.”

“Yes,” said Oscar. “Mr. Sherard and I have just been admiring it—together with the last head it claimed.”

“I’m so glad,” purred Mr. Tussaud. “In its way, it is a thing of beauty; almost a century old, but still in perfect working order. The craftmanship’s extraordinary. It was in use until just three years ago. I acquired it from the French authorities for a tidy sum. I knew in my bones that my great-grandmother would have wanted us to have it here. She was a remarkable woman. Have you yet seen her death mask of Marie Antoinette? It’s one of her best.” Our host’s spectacles glinted in the gaslight as he raised both hands and beckoned us to follow him.

He led us away from the throng and through an unmarked door, across a darkened corridor, and through a second door into a smaller exhibition room, entirely lit by candlelight. There were no crowds here, just half a dozen visitors standing behind a rope cordon gazing at an assortment of individual human heads lolling on scarlet cushions.

“This is my favourite room,” said Tussaud, lowering his voice once more and gesturing proudly towards the exhibits. “Look. To the left, we have the revolutionaries. Robespierre is the third one along. And to the right—slightly elevated, you notice—we have Louis XVI and his queen.”

“Their faces appear to be larger than those of the revolutionaries,” said Conan Doyle, gazing at the waxed visages of the royal couple.

“They are larger, Arthur,” said Oscar quietly. “They were better fed.”

“And behind you,” announced Tussaud in an excited stage whisper, “we have Citoyen Marat, murdered in his bathtub by Charlotte Corday.”

“Oh, my,” murmured Oscar, turning round, “that is most lifelike.”

“Marie Tussaud was among the first on the scene.”

“In at the kill,” whispered Oscar, impressed.

“She made it her business,” said Tussaud earnestly. “It was her business. She told the story of her time. She was an artist—a portraitist who worked in wax instead of oils. Monsieur David’s famous painting of this very scene is based on her waxwork. Monsieur David was a family friend. So was Marat. And Rousseau. And Benjamin Franklin. Marie made models of them all. She knew all the great men of the age. And the women, too.”

“I envy her,” said Oscar quietly, turning his back on the bath and surveying once more the row of severed heads. “I should have liked to have met Queen Marie Antoinette.”

“You have met Queen Victoria, haven’t you?” asked Arthur playfully.

“It’s not quite the same thing,” murmured Oscar.

“Marie Tussaud met everybody,” repeated her great-grandson proudly.

“Oscar’s met everybody,” I said defensively.

Oscar smiled. “Not Robespierre, alas.”

“But you met the man who tried to assassinate Queen Victoria, didn’t you?” I persisted.

“I did, Robert. Once. And very briefly.” He turned to John Tussaud, adding by way of explanation: “The man was an unhinged versifier named Roderick Maclean. A poor poet and a worse shot.”

Mr. Tussaud laughed and looked at his watch. “It’s lunchtime, gentlemen. I want to hear all about Queen Victoria’s failed assassin over our lobster salad and roast pheasant.”

“Lobster salad?” repeated Oscar happily. “Roast pheasant?” He looked at Conan Doyle with shining eyes. “You are the best of friends, Arthur, and you have the best of friends.”

“I’m taking you to our new restaurant,” explained John Tussaud. “We shall dine by electric light to music provided by Miss Graves’s Ladies Orchestra. They have promised to give us a selection of tunes from the Savoy operas.”

“Gilbert and Sullivan,” said Oscar genially. “I have met both of them.”

“Oscar’s met everybody,” I repeated. “Poets, princes, artists, assassins …”

John Tussaud was leading us towards the stairway at the end of the exhibition room. We passed a familiar profile. “Yes,” said Tussaud, nodding at the bust: “Voltaire. Marie Tussaud knew Voltaire.”

Oscar paused. “How I envy her!” He sighed. “I met Louisa May Alcott once,” he said, “the author of Little Women. She was a little woman.” He gazed fixedly at Madame Tussaud’s head of Voltaire. “And I met P. T. Barnum,” he added. “And, through him, of course, I met Jumbo the Elephant. It’s not quite Voltaire, but it’s something.”

Conan Doyle burst out laughing. “You’re impossible, Oscar!” he cried. “Jumbo the Elephant? I don’t believe you.”

“It’s true,” protested Oscar.

“It can’t be.”

“Give him the manuscript, Robert.”

I handed Conan Doyle the parcel that I was carrying.

“This is my Christmas present for Arthur,” Oscar explained to John Tussaud. “It’s some holiday reading, something for him to puzzle over at his Southsea fireside.”

The manuscript was wrapped in brown paper and tied up with string. Conan Doyle turned it over slowly in his hands.

“They’re all there, Arthur,” said Oscar teasingly. “Louisa May Alcott, Jumbo the Elephant, the man who tried to shoot Queen Victoria …”

Conan Doyle looked up at Oscar and furrowed his brow. “What is this?”

“As I say: your Christmas present, Arthur. Last year you gave me The Sign of Four. This year I’m giving you this. It’s a manuscript—and a challenge. It’s a story from my salad days, an account of a year and a half of my life—a while ago now. Before I was married. Before I was a family man. Before my responsibilities had made me fat. The story begins in 1882, when I was in my mid-twenties, footloose and fancy-free. A time when I travelled the world and came to know some remarkable men and women. Not Robespierre and Marie Antoinette, not Voltaire, to be sure, but remarkable nonetheless: Longfellow, Walt Whitman, Sarah Bernhardt, Edmond La Grange … Names to reckon with—and people you’ve never heard of.”

Conan Doyle balanced the package on the palms of his hands as though assessing its weight. He brought it up to his face, as if by sniffing at it he might better estimate its value. “Is it autobiographical?” he asked.

Oscar smiled. “It’s my story, Arthur, but it’s Robert’s handiwork. Robert is my recording angel—my Dr. Watson. He witnessed much of what occurred in France himself, as you’ll discover, but I saw it all as it unfolded, from its beginnings in the New World. This is a tale that starts on one continent and travels to another. I want you to pay close attention to the beginning, Arthur. The beginning does not merely set the scene; it lays the groundwork for what is to come.” Slowly, Oscar ran his forefinger along the string that held the brown paper parcel together. “This is a true story, Arthur. I suppose you’d call it a murder mystery. It can’t be published—at least, not in my lifetime. Much of it is libellous. Some of it is salacious. And, as yet, the story is incomplete. The manuscript’s unfinished. It lacks the final chapter. I want you to read it, Arthur. I want you to read every word, even though some of it will make you blush. If you like, you can show it to your friend, Sherlock Holmes—he’s made of sterner stuff. And then, when you’ve read it, and pondered long and hard, I want you to tell me what you think the final chapter should reveal.”

Oscar turned back to our host and widened his eyes. “Now, Mr. Tussaud, kindly lead us to your lobster salad. The sight of all these wax cadavers has given me the most tremendous appetite.”

What follows is the manuscript that I gave that day to Arthur Conan Doyle.

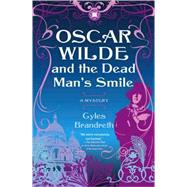

© 2009 Gyles Brandreth

1On 24 December 1881 Oscar Wilde set sail for the United States of America. He went in search of adventure and gold. Within weeks, he had found a portion of both.

Oscar had recently turned twenty-seven and, in England, his claim to fame was that he was famous for being famous. He was a celebrity, in the tradition of Lord Byron and Beau Brummell, but more Brummell than Byron, more style than substance. “Evidently I am ‘somebody,’” he noted at the time, “but what have I done? I’ve been ‘noticed.’ That is something, I suppose. And I have published one book of poems. That doesn’t amount to much.”

As a young man, first at Trinity College, Dublin, and then at Magdalen College, Oxford, Oscar had achieved every academic honour within his reach. He rounded off his undergraduate years by securing an Oxford double first and winning the coveted Newdigate Prize, the university’s chief prize for poetry. But what was his real ambition in life?

“God knows,” he said, when asked. “I won’t be an Oxford don anyhow. I’ll be a poet, a writer, a dramatist. Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious. Or perhaps I’ll lead the life of pleasure for a time and then—who knows?—rest and do nothing. What does Plato say is the highest end that man can attain here below? ‘To sit down and contemplate the good.’ Perhaps that will be the end of me, too.”

When Oscar left Oxford, cushioned by a modest legacy from his late father, he floated down to London, the capital of the British Empire, and made his mark on the metropolis with outlandish views and an outrageous appearance. “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances,” he declared. He had always been partial to dressing up. In his last term at Oxford he appeared at a ball disguised as Prince Rupert of the Rhine. In his first season in London he took to going out in a bottle-green velvet smoking jacket edged with braid, wearing a cream-coloured shirt with a scalloped collar and an overabundant orange tie, taffeta knee breeches, black silk stockings, and silver-buckled shoes. He became a champion of beauty and a self-styled professor of aestheticism. “Beauty is the symbol of symbols,” he declared. “Beauty reveals everything, because it expresses nothing. When it shows us itself it shows us the whole fiery-coloured world.”

The young Oscar Wilde was determined to be noticed.

And he was. Soon after his arrival in London, the satirical magazines of the day started to publish spoofs and squibs at his expense. He was lampooned in music-hall sketches, in stage farces, and then, most famously, in April 1881, in Richard D’Oyly Carte’s hugely successful production of W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan’s comic operetta Patience. Oscar was at the first night and gently amused. He recognised the piece for what it was: not a personal attack on him, but a pleasingly tuneful skit on the absurdities of the aesthetic movement.

The success of Patience changed Oscar’s life. On 30 September 1881 he received a telegram from Colonel W. F. Morse, Richard D’Oyly Carte’s business manager in New York, inviting him to undertake an American lecture tour to coincide with the operetta’s American production. Oscar did not hesitate. On 1 October 1881 he wired his acceptance to Colonel Morse. The young poet was in want of money and exhilarated by the prospect of crossing an ocean and discovering a continent. “I already speak English, German, French, and Italian,” he explained to his mother. “Now I shall have the opportunity of learning American. It will be a challenge, I know, but I must try to rise to it.”

He wrote to James Russell Lowell, the United States minister in London, presuming on their nodding acquaintance to ask for some letters of introduction. The venerable Lowell, then in his early sixties, replied that “a clever and accomplished man should no more need an introduction than a fine day,” but as he liked Oscar, was amused by him, and, a poet himself, admired the young man’s verses, he was happy to oblige.

As well as letters of introduction, Oscar equipped himself with a new wardrobe, including a warm Polish cap and a befrogged and wonderfully befurred green overcoat; Lowell had warned him about the New York winters. And because Colonel Morse had advised him that he would be lecturing to “huge audiences in vast auditoria,” in the weeks before his departure, Oscar engaged the services of an expensive expert on oratory to give him elocution lessons. “I want a natural style,” he told his instructor, “with a touch of affectation.” Oscar Wilde prepared carefully for his American adventure. He hoped that it might prove the “making” of him.

Oscar set sail from Liverpool on the afternoon of Christmas Eve 1881 on board the SS Arizona. He was apprehensive. The Arizona was the fastest steamship then crossing the Atlantic, the holder of the Blue Riband, and the young aesthete did not much care for speed. The Arizona had also recently survived—but only narrowly—a mid-Atlantic collision with an iceberg.

In the event the crossing was calm and hazard free. It was the arrival that proved more of an adventure. The Arizona docked in New York harbour on the evening of 2 January 1882. It was too late to clear quarantine, so Oscar and his fellow passengers were obliged to spend a further night on board ship. The gentlemen of the New York press, however, were impatient for a first sighting of the much-vaunted Mr. Wilde. They would not wait till morning. They chartered a launch, came out to sea, and, in Oscar’s phrase, “their pens still wet with brine, demanded that I strut before them, like a prize bantam at a country fair.”

The journalists were a little taken aback by what they found. Oscar was not the delicate exotic that they had been expecting. According to the man from the New York Tribune:

Oscar did not engage his interlocutors in fisticuffs, but nor, in the main, did he endear himself to them. “I tried to be amusing,” he later confessed, “and engendered snarls where I had hoped for smiles. My efforts at drollery were taken for disdain.” He was asked how he had enjoyed his ocean crossing. He replied, “The sea seems tame to me. The roaring ocean does not roar. It is not so majestic as I expected.” His remarks appeared beneath the headline: “Mr. Wilde Disappointed with the Atlantic.” He gave the impression of arrogance.

And he compounded that impression on the morning after his shipboard press conference. Disembarking from the SS Arizona and passing through customs, he responded to the customs officer’s predictable enquiry, “Have you anything to declare, Mr. Wilde?” with a well-prepared reply: “I have nothing to declare except my genius.”

Some thought this vastly amusing. Others thought that young Mr. Wilde was riding for a fall. And, to an extent, he was. His first few lectures were not a success. He said too much, too quickly, and in too soft a voice. He failed to hold the attention of the crowd. His audiences were disappointed; the critics were unkind.

In public, Oscar was undaunted. In private, he acknowledged that he had work to do. He simplified his lecture; he improved his presentation; he moderated his language; he added some jokes that everybody could understand. He turned a potential disaster into an unquestioned triumph. Ultimately, during the course of 1882, Oscar delivered a total of more than two hundred lectures in one hundred and sixty towns and cities across North America, from New Orleans to Nova Scotia, from northern Massachusetts to southern California. “Oh, yes,” he would say in later years, “I was adored once, too. In America I was obliged to engage two secretaries to cope with the correspondence—one being responsible for the demand for autographs, the other for the locks of my hair. Within six months, the first had died of writer’s cramp; the other was entirely bald.”

In fact, Oscar did have two companions on his travels, but neither was a secretary. Colonel Morse supplied him with a “man of business,” a clerk from D’Oyly Carte’s New York office, named Aaron Budd, and a personal valet, a young Negro called W. M. Traquair. “I did not care for Mr. Budd,” said Oscar. “He looked after our railroad tickets and counted the takings. He was efficient, but not interesting. He rarely spoke, he never smiled, and the pallor of his skin was disconcerting. I believe he was an abstainer and a vegetarian. By contrast, I cared a great deal for Washington Traquair. His father had been a slave. He was my servant, but he was also my friend. He was not a great talker and he could neither read nor write, but he had a wonderful smile and he laughed at my jokes. You have to love a man who laughs at your jokes.”

In the course of his tour, Oscar made a great deal of money and, as he put it, “a rich assortment of new acquaintances.” In New York, he met the celebrated novelist Louisa May Alcott, then in her forties and at the height of her fame. “She was a small but profoundly passionate woman,” he recalled. “She told me the plot of a story that she was revising at the time. It was entitled A Long Fatal Love Chase. As she recounted the tale, she held my hand in hers and tears filled her eyes. I asked her why she had never married. ‘Oh, Mr. Wilde,’ she said, ‘if I tell you, will you keep my secret? It is because I have fallen in love with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.’”

It was in New York, too, that Oscar met the great showman Phineas Taylor Barnum. Oscar was lecturing at the Wallack’s Theater on Broadway and Barnum came with a party of friends “to see what all the fuss was about.” What Barnum made of Oscar’s disquisition on “Art and the English Renaissance” history does not record, but Oscar reckoned the encounter a success. “When I spoke to Mr. Barnum of Giorgione, Mazzini, and Fra Angelico, he assumed they were a trio of Italian acrobats. Mr. Barnum lacked education, but he had style. He came to my lecture and I visited his circus. After the spectacle, at my insistence, he introduced me to his prize attraction, Jumbo, the African elephant. ‘I must meet him,’ I told Mr. Barnum. ‘His name will be remembered long after ours have been forgotten.’ ‘I should hope so, Mr. Wilde,’ answered Barnum. ‘He cost me ten thousand dollars.’”

Oscar brought back many good stories from his year on the American lecture circuit. Probably his favourite anecdotal set piece concerned his time in Leadville, Colorado, high up in the Rocky Mountains. There he addressed audiences consisting of ordinary working-men—labourers and mine workers in the main. Because the miners were mining for silver, Oscar chose to read to them extracts from the autobiography of the great Renaissance sculptor in silver Benvenuto Cellini. “I was reproved by my auditors for not having brought Cellini with me. I explained that he had been dead for some little time, which information elicited the enquiry: ‘Who shot him?’”

When, later, Oscar was asked if he had not found the miners “somewhat rough and ready,” he replied: “Ready, but not rough. There is no chance for roughness in the Rockies. The revolver is their book of etiquette. This teaches lessons that are not forgotten.”

The mayor of Leadville, one H. A. W. Tabor, known as the Silver King, invited Oscar to visit the Matchless Mine and open a new shaft named the “Oscar” in his honour. Oscar was delighted to oblige and, dressed in his aesthete’s finery, was ceremoniously lowered into the mine inside a huge bucket. Once he had inaugurated the new shaft, employing a special silver drill for the purpose, the miners invited him to dine with them at the bottom of the mine. “They laid on quite a spread,” he recalled. “The first course was whisky; the second course was whisky; the third course was whisky; I have little recollection of the dessert.”

That evening, Mayor Tabor offered Oscar further entertainment at the Leadville casino. According to Oscar, “Drinking rather than gambling appeared to be the business of the place. It was crowded with miners and the female friends of miners. The men were all dressed in red shirts, corduroy trousers, and high boots. The women wore brightly coloured evening dresses cut so low that their breasts were almost entirely exposed. The floor was covered with sawdust and the walls hung with huge, gilt-framed mirrors. In a corner of the main saloon was a pianist, sitting at an upright piano over which was a notice that read: ‘Don’t shoot the pianist; he is doing his best.’”

On his second (and final) night in Leadville, Oscar returned to the casino. This time, he went alone. Mayor Tabor had business to attend to in Denver; Aaron Budd, Oscar’s business manager, was not a drinking man; and Traquair, the valet, was barred from entry because of his colour. Oscar began the evening by the piano, surrounded by young men in red shirts and young women with full bosoms. He made them laugh and they made him smile. Four and a half hours later, having eaten nothing and drunk too much, he found himself in a different, darker corner of the saloon, seated alone with two men in check shirts and a young woman who leant towards him across the table, dusting her breasts playfully with a little lace handkerchief. As one of the men plied Oscar with drink and the other removed his wallet from his coat pocket, two pistol shots rang out across the room. One shot blew the whisky glass from Oscar’s hand; the other sent his wallet spinning into the air.

Instantly, as the shots were fired, Oscar’s trio of drinking companions fled the scene, and Oscar, bewildered but unharmed, slumped slowly to the floor. The man who had fired the shots crossed the room, helped Oscar to his feet, and accompanied him out of the casino, down the deserted street, and back to his hotel. The man’s name was Eddie Garstrang.

© 2009 Gyles Brandreth