Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

A hundred secrets will be known

When that unveiled face is shown.

FARID UD-DIN ATTAR,The Conference of the Birds

Once upon a time here in Smyrna, a city as ancient, as infamous as the Olympians, the gods had changed a king's daughter into a myrrh tree for incest. The love child of the trespass, Adonis, was born from her split trunk. Adonis was so handsome that Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty herself, coveted him as a lover. Her only true love -- really. Fruit of a tree.

Since then, a deep, palpable humming pervades this town of rumors. Maybe even before; surely even before. All you have to do is listen; you can hear so much -- the birth cry of St. Paul, the scratching of St. John's quill as he labors over his Gospel. Through the fog, you can see Anthony and Cleopatra, lost in horrid ecstasy, floating on a golden barge. Or a vision of Mother Mary deep in meditation, mourning for her dead son. It all happened here. They all occupied this same land, along the same sea. The Aegean. The mirror of mirrors.

On the Bay of Smyrna, the air always smells of rotten plankton and salt. Clusters of debris lap ashore, gathering into sculptures of melon skins, cardboard, and kelp. Across the Bay, one can imagine Homer gleefully watching Odysseus' ship gliding across and composing theOdyssey.Four thousand years later, in retaliation, the defeated Greek army burns all memories, at least so they say -- all in this lifetime. But the smell of ancient ashes never subsides. The embers from time immemorial still smolder beneath the Bay (some say, the lava of Hades' breath), long before the great fire almost consumed all. Here, it's unavoidable. To go back in time. Live past lives. Be other people. Some places store memory. This is one.

I was built in Smyrna in 1890, the year of Esma's birth. A slender, many-roomed Victorian dwelling of wormwood, snuggling against an unworldly, umbrageous rock -- obsidian, rumored to have been lowered down from the sky, the rock that gave the district its name: Karatash, or Black Stone.

My balcony and the windows are covered with trellised fenestration that conceal the harem apartments, where jasmine and pomegranate vines cling to the facade, and linden and horse chestnut provide shade from the intense Aegean sun reflecting off the most saline, the most turquoise water. Acayiqueperpetually bangs against a hollowed marble dock, remnant of an ancient Lydian water temple. (The outbuildings were built much later to house the servants and also served as kitchen and laundry rooms.) The stained glass dome of thehamam,vapored from the steam of the baths below, against the skyline stands like the silhouette of a forlorn Mughal villa. Different than the rest.

Some believed that the myrrh tree in the garden was the actual Adonis tree. They believed it was sacred and left votives and humble offerings on the double altars of its fracture. Others took it to be an ordinary myrrh cracked by natural forces. Over the years, its persistent branches stretched into Esma's room and, later Amber's, becoming the center of mysterious incidents. Like the time a hand burst out holding an amber egg with a frozen moth inside; or when a triple lightning burned it to the ground, only to be reborn the following night.

For the first twenty-eight years of my life, a Pasha lived here with his harem -- three wives, servants, and various offspring. The Pasha himself stayed in the boathouse annex, conducting otherworldly business -- an unscrupulous and selfish rich man concerned only with his vanities -- cultivating the white opium poppy and belittling the unfortunate. After the exile of the Sultan, the Young Turks, declaring him guilty of unspeakable crimes, exiled him to the purgatorial ice lands of Kars where, they say, he committed even worse things. They say, old dust never settles. That's another story.

But the women in his harem, suddenly finding themselves with no sustenance and nowhere to go, and no resources to keep me, had to flee in a terrible hurry, abandoning their splendid clothes, fine china, and priceless furniture. It was at this juncture that Esma arrived, just at this instant of their imminent departure as if on a theatrical cue.

A hazy winter afternoon. Shrouded and veiled in black, she arrived with a go-between, walking three steps behind her older brother Iskender, her identical sons -- Cadri and Aladdin -- clinging to her skirt. (You can always tell orphans.) And three paces behind followed her two maids, Gonca and Ayse, heads down, furtive steps.

Like an apparition, Esma shuffled from room to room, as if talking to the invisible faces on the walls, touching and smelling objects that caught her eye, chanting prayers. She opened the doors to every room cramped with dusty episodes, the basement resonating with the constant sound of dripping water from thehamam. Tip, tip, tip.How to fill the emptiness, revitalize the neglect. Yes.

Out the back window of the third story, she saw the black rock, the cracked tree. Felt the tremor from the lapping of the waves against the stilts. Her eyes watered. She had come home. Love at first sight.

"The house could be yours for nothing," whispered the go-between, who followed her into the attic strewn with the indulgences of women from a distant era -- balloon pants, satin slippers, gauzy veils. "Number One Wife desperate to get rid of it all. They have nowhere to go. They must leave the house by dawn."

Esma ignored her and returned to the harem where the women offered her coffee and confections. They watched intently as she removed her kid gloves, squeezed a sapphire ring the size of a hazelnut -- a last vestige of her dwindling jewels -- and slid it on the Number One Wife's finger.

It fit perfectly.

"Payment for the house," Esma told her.

The older woman began to weep, tried kissing her hand in gratitude, which Esma would not allow. Esma put her arms around her until she stopped sobbing.

From that moment, we were inseparable. Even after death.

Each time she heard the story, "What happened to the harem ladies?" the child Amber would ask.

"A sad story. Their eunuchs took them from village to village in distant lands of Europe and displayed them as curiosities. Sort of like dancing bears."

"Why?"

"Because they were nameless and had no other place to go. No one to claim them. They were stolen from their homes so long ago that no one remembered them anymore."

"I can't allow you to live in a strange city all alone! In a big house like this! Who is to protect you? What will the people think?" her brother Iskender paced, exasperated. "Stop being so stubborn and come to the plantation. The boys must have other men around! A woman shouldn't stray from her family."

"This is my home," Esma was firm. "I must stay in Smyrna. Where my husband brought me as a bride. I have the girls to help me. We'll find our way somehow. God is on our side."

"The girls" were the two Kurdish odalisques, the servants -- Gonca and Ayse they were called -- gifts from Esma's brother-in-law, the kind-hearted Mim Pasha. I heard their story repeated many times over and over again. How four little girls, sisters, lay half dead among the debris of a massacred village in the region of Mount Ararat. With admirable heroism, Mim Pasha had saved their lives and brought them back as gifts for his wife, Mihriban, and for Esma. Now they belonged to the family.

"It breaks my heart to see you like this. But you've been stubborn since you were born. Remember, though, no one knows what fate brings. If you ever change your mind, you always have a place with me," Iskender told Esma before returning to the silk plantation in Bursa. "Rain or shine. Don't forget to remember."

"I'll remember."

Could they have known as he rode away? Could they have known how fate would soon pull them apart?

The picture of the stern gentleman in the white turban, old enough to be her father, instead belonged to Esma's husband, recently deceased. Forced to sell her finest jewelry in order to survive after his death, except a precious stone or two and a few yards of sumptuouscrepe d'amour,crepe of love. Genuine silk. The finest of all for a wedding gown. But never to be her own. Nor her daughter's -- at least on her wedding.

How do I know these things, these inconspicuous things that fill the space between the walls? I listen. I listen to everything, their synchronous breathing at night, the whispers hissing like snakes on all floors, the sounds of their dreams, the impact of cat paws against the cool cellar leading to the subterranean catacombs under the city. I listen to the children's voices echoing and expanding in the tunnel beneath; as if the Minotaur of the cave is blasting fire out of its nostrils. Or the streetcar tooting its horn like a capricious siren each siesta afternoon; and at midnight, the night watchman's stick striking the cobblestones.Tap, tap, tap. Rap, slap, clap.

Every night, when the town sank deep into slumber, the distant voice of a woman's singing seemed to be rising from the depths of the Aegean."Dandini, dandini, danali bebek. Elleri kollari, kinali bebek."My little babe, whose arms and hands are hennaed, oh my little babe. She was singing a lullaby to an infant resting in a secret place nearby. Gone mad when her baby died, she'd buried it in a golden cradle, then offered herself to the waves.

Esma always lay in bed listening to this lullaby, muffled from having to pass through a curtain of fog -- itself an apparition. The lullaby stole quietly into her room, wrapping her entirely in its fluid warmth, whispering,"Dandini, dandini, danali bebek."

When the boys asked if it was the sirens singing, she told them, "There's no such thing. I once thought I heard the sirens, too, when I was a child but later, later they disappear. Ignore them; they're nothing but the spit on the devil's tongue. Their songs wreck ships and those they lure meet unspeakable deaths. Once, a man named Odysseus tied his men to the mast so the sirens' voices could not entice them. It was the only way."

I listen and peer into their lives -- the most private moments when they close their doors and retreat into their private dreams. I even see those dreams. I read their thoughts. Make judgments. Even manipulate situations when I can. I, too, have frailties.

I look in on the boys asleep in the room they share. And just outside, Gonca, the ageless odalisque with the mustache whose eyebrows meet in the center, the one who dries bat wings for good luck and pulverizes sea horses, sleeps mattressless on the floor -- the only way she knows to sleep -- and breathes in harmony with the children. After a while, their exhalation takes on colors, continuously dissolving into new shapes and spiraling into a common dreamworld and fall, fall and fly, fly and float.

Before retiring, Gonca always locks up her sister Ayse. The moon makes the young girl wild and frenzied. As if in heat, Ayse stirs like a boa, aroused by her own writhing. Her bed in the night, always drenched, her jasmine vapor always steaming.

On the third floor, Esma untangles her waist-long hair, her sunken eyes flashing like jewels in the dark, her heart flying, and her mind alert. She parts the curtain, seeing no one. Suddenly, the muezzin's voice rises like a raptured bird as he begins the midnight prayer. Esma covers her hair, rolls out her prayer rug from Ushak. Stands facing the East, joins her fingertips, and mumbles incomprehensible incantations. She rubs her face slowly, her willowy figure crumbles, her forehead kisses the floor.

The curtains billow in the wind, the balcony door parts, and wearing a fez and a pelerine, Süleyman arrives like a Valentino sheik. His hawk nose bespeaks of his wild nomadic ancestors who once crossed the Urals and the Altays. He is like a lean mountain gazelle, open chested, his heart pulsing with his smile. Pearl white teeth, searching eyes.

Quickly, Esma rolls the prayer rug under her bed. Adjusts her hair. Süleyman's the only man to see her without her veil outside of her family. He removes his fez and bows to her. Then, they sit on the heirloom Louis Quinze couch, to watch the moon, if there is one in the sky. If not, the stars, if it's a clear night. Their heartbeats harmonize. And their breath.

Now and then, distracted, they glance at each other instead of the sky. They peer with burning eyes, but hands, hands they restrain. Never to touch, the vow they made, the vow that allows them to come together like this every night. For years. To love like this. Without a blemish.

He asks her, "Esma, Esma, why won't you become my wife?"

Esma casts down her eyes. Still in widow's black.

"Once there was, once there wasn't," she begins with the words that begin all stories. "Once, a nightingale loved a rose. And the rose, aroused by his beautiful song, woke trembling on her stem. She was white, as all roses were in those days. But she had tears of dew."

"The nightingale came ever so close and whispered, "I love you, rose," Süleyman continues where Esma left off, "which made her blush, and instantly pink roses burst out of their buds. Then, the nightingale came closer. Allah meant the rose never to know earthly love but she opened her petals and the nightingale stole the nectar. In the morning, the rose, in her shame, turned red, birthing red roses."

"Ever since then, the nightingale visits her nightly to sing of divine love, but the rose refuses, for Allah never meant a flower and a bird to mate. Although she trembles at the song of the nightingale, her petals always remain closed," she terminates.

A moment of silence.

"Three apples have fallen from the sky," they then recite in unison. "One belongs to the storyteller, one to you, and one to me."

And one to the walls that can hear and see all.

They laugh. This is how all the stories end. Until the dawn prayer, they recite poems and stories to each other like this, to compensate for all they cannot fulfill. No one else will know of their secret world in which love is transcendent and suffering a joy.

Each time they part Esma gives Süleyman a handkerchief full of something, like the most delectable Turkish delight from Hadji Bekir. Süleyman bows, puts on his fez, and blends into the dusk. Esma unrolls her prayer rug, joins the tips of her fingers together, falls prostrate, an enigmatic smile on her face. In that position she stays, curled like a fava bean, on her prayer pod.

This happens every night. Well, almost...

In the morning, Gonca, finding her mistress like this, covers her with the silk blanket woven of millions of cocoons, her brother Iskender's gift -- the finest silkmaker in Bursa, they say. The one who will arrive that day and will change their lives.

Gonca can smell man in the room. She knows. Like me, she knows but will not talk. She knows, if others were to know, they might stone her mistress. Or cause other unspeakable torments. Esma could be defaced, and the man, exiled. She can't forget the image of the woman she once saw in the desert, buried up to her neck in the sand and her accomplice up to his waist, left to the vultures of kismet.

As the night predators flee the sun, a new cast of characters, the yogurt-man, the rag-seller, the bundle-ladies pass by, staring at me. I could sense they are imagining a procession of ghostly images, as if a veil has been drawn over this timeless face. House of dreams, they whisper to each other.

In daylight, legitimate this time, Süleyman arrives again rowing hiscayique.Sükrü, the running boy, greets him at the dock and leads him to the Learning Room -- piled with old maps, peculiar medical instruments that once belonged to the boys' father -- a great scholar, everyone says -- the serried, dusty volumes, almost murmurous with accumulated meaning, arranged meticulously along the high walls.

But the most compelling object for the boys is a skeleton for their anatomy lessons. It's of a very short person they have endearingly named "Yusuf." They tell stories of him before he became a skeleton.

Dressed in their black suits, they approach Süleyman and kiss his hand. He pulls their ears affectionately; then, all of them sink down at a low table with intense male seriousness. Süleyman knows how to draw them to himself.

The boys wait silently as their teacher slowly stirs his tea.Clink, clink, clink. Slurp.Cadri always dreamy, Aladdin restless twirling his pencil.

They recite verbatim the previous day's history lesson. The conquest of Constantinople. How their Great Sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror, stretched oiled sleds across the Galata and slid his ships into the Golden Horn, vanquishing the ancient city of the Byzantine Empire.

"And when did this occur?" Süleyman asks.

"1453," Cadri effortlessly replies before the question mark. "When the crescent broke the cross."

"Does anything make that date special?"

"Yes, that was the event that ended the Middle Ages. The Islamic people overpowered the Christians. They turned the churches into mosques."

Or they recite how their great admiral Barbarossa was losing his fleet in the Mediterranean until a crescent and a bright star, Venus really, formed in the sky, a divine omen that changed the course of history. It takes a heavenly incident like this to change fate. Any fate. Anywhere.

Or the story of thecroissant.How the Turkish invaders were advancing toward the gates of Vienna with their crescent and star banners and how the bakers of the city concocted crescent-shaped rolls to warn their people to mobilize. Odd, how this common breakfast pastry once saved Europe from the sons of Allah. If the Turks had succeeded in passing through those gates, imagine what could have happened to the Western civilization!

Süleyman makes them repeat:Calligraphy is a spiritual geometry manifested by a physical instrument or device, strengthened by constant practice and weakened by neglect.

Cadri copies the words slowly in ornate calligraphy -- from the back of his notebook, to the front -- and from right to left, the way his mind moves, from right to left. The way it would be the rest of his life even when everything changes. From right to left.

But Aladdin's eyes, they wander far, counting every ship leaving the harbor. Forty-seven. Forty-eight. Forty-nine. Words don't interest the boy. The magic of numbers forming and reforming themselves. He is already far into his calculus. Eyes drifting across continents, across constellations.

"Where do your eyes wander, my son?" Süleyman asks.

"What is beyond the Aegean?"

"The Mediterranean."

"And beyond that?"

"The Atlantic Ocean."

"And beyond that?"

"America. The unknown continent Cristophe Colombe discovered."

"What about the Red Skins?"

"They were already there."

"So, how could he discover a place if people were already living in it? It would be theirs."

"You see the truth, my boy."

A pandemonium outside. Veiled women arrive in theircayiques paddled by their eunuchs or inphaetoncarriages. They can hear the voices from the learning room.

"Yo-ho."

"Yo-ho, yo-ho,Esma. Are you home?

The girls take the guests' bundles up to thehamamand the food they brought to the kitchen. The women remove their veils. Esma kisses each on both cheeks and, sitting at the edge of her seat, serves them freshly ground Turkish coffee in thimble-sized cups.

"How are you?"

"Fine. And yourself?"

"Masallah.No complaint."

"And the boys?"

"They, too. Just fine. And your household?"

"Not so fine. That spoiled new wife throws jealous tantrums."

"Pray tell."

"Oh, she's a young blossom, you know. Not keen on men's nocturnal wanderings. She will soon compromise."

An older woman weeps. "My sons joined the army."

"Vah, vah!"

"But the war is over."

"They say there will be another one."

And so on. And so on.

They scurry up the stairs into thetepidarium,remove their clothes -- everything -- put on high wooden clogs, wrap themselves in soft Bursa towels before entering the vaporous sanctuary. There, they stay all day, camouflaged in the silver mist, all breasts and hips, ladling water out of marble basins, rivulets of henna running through the small gutters, scent of lilac and muguet mingling with the foul odor of muddy depilatories, their hollow voices bouncing off the walls muffled by the steam to the skylight as pink as Turkish delight. They wash, they scrub each other, buffing the skin with pumice and loofah, extracting noodles of dirt that swim in the rainbow-colored water, running under their feet like freshly hatched tadpoles.

In a private corner, the old women pour blue powder into copper pots and rinse their white hair with indigo to achieve a fluorescent sheen. Afterward, they wash their underwear with small cakes of the same in marble sinks.

They watch each other. The older women watch the bodies of the young girls; it gives them pleasure. Yet, they are jealous of the luminescent skin, the unnursed breasts, the unspoiled vaginas. The young girls wear evil-eye charms on their ankles or wrists to protect themselves from bad spells. Transfixed on clusters of cellulite, the infinite forms of breasts, the w-shapes where the legs meet, the children gape at everyone.

These women, chefs of depilatory, masters of lemon paste, slap patches on their pubis, arms, legs, even the crevices inside nostrils, inside ears. Yank out all hair, whimpering in pain. God created woman without hair. Only after the great sin her hair grew like other animals. It's the memory of her shame. Any sign of it must be obliterated.

So, this is the daily life here, more or less, day after day, but today things are slightly different because Iskender is visiting from Bursa. He has come to persuade his sister to take her boys and come back to the silk plantation in Bursa where he is convinced they would be safer since there are rumors that the allied forces intend to occupy Smyrna.

Meanwhile, he is doing a bit of business. Ferret, an associate who comes to call on him, steals into the washroom on his way up the stairs, peeks into thehamamthrough a hole on the wall that he himself has pried. His arteries burst as if filled with noxious gas. Watching the women's private nudity, his breath grows leaden, his hands slide into his trousers -- shaking with grotesque contortions.

For months, he's been pursuing Esma's scent through the corridors, inhaling the rooms she had recently walked through, licking the walls, fondling the drapes. A man of such lickerous and unsavory intentions.

Around noon, steaming bodies sprawled out on the cool tiles. The beautiful male voice of the muezzin resonates outside -- way outside, in a world unkind to them. It rises into the heaven as if he is drinking the song of its deity. In unison, the women raise their palms, standing in a circle, mumbling mysterious prayers.

Meanwhile, in the enormous cellar, the girls work, their hands deep in flour and eggs. They roll huge circles of dough, paper thin, stack the circles on big trays, layering with eggplant, pistachio, figs. The running boy, Sükrü, rushing to the brick furnace down the street, a tray in each hand held above his head like some Corinthian caryatid, his perfect balance, his golden sinewy arms, his blond mustache making the girls giggle and blush.

Gonca flushes at the sight of him but he's got the hots for her curvaceous sister Ayse. He sneaks through the watchman's path and comes to Ayse's window each dawn, on his way to the bakery. Bars separate them but only at arm's length. She bares her breasts for him, one at a time. Sometimes he brings her grape molasses and she lets him touch her nipples and tweak them. Sometimes tahini. They coo and gurgle unimaginable ecstasies that awaken the roosting doves.

Iskender has invited the Ferret formezesandraki-- the transparent liquid that the dervishes call "white writing," or invisible ink. The Ferret, squishing the seeds out of a plateful of olives with his fat fingers, watches out the window, the boys waving at Süleyman's disappearingcayique.

"The boys need a better education," the Ferret tells Iskender. "Why don't you send them to the Sultaniye school?"

"My sister prefers a private tutor. Süleyman is a clever lad. Educated. Inventive. The boys like him."

"But an empty pocket," Ferret says. "With holes in it. Hair down to his shoulders, clothes like those degenerate Frenchmen. Libertine ideas admittedly borrowed from the Young Turks. Bad example for the boys whom I myself hope someday to parent."

"Ah!" Iskender takes a long sip of hisraki,avoids the insinuation. He won't disclose to this impudent his plans of taking his sister back. "Süleyman is a fine lad. Sincere. Honest. Well mannered. Nice."

"Only if one is blind to vice."

"Meaning?"

"Well, there's talk..." A wry smile. The Ferret whispers something in Iskender's ear.

Iskender's eyebrows meet in a frown. He asks the Ferret to leave.

That night, Iskender reclined in front of a blazing brazier, smoking his secret affliction while he watched a ghostly procession parade endlessly across an invisible screen. His pain stopped, all edges dissolving into a continuous flow. Whispers throughout the city stretched like taffy. Strains of music in distant rooms, runaway phrases. Deep bass of the fog horns. The lamenting woman's lullaby as she rocked her golden cradle. Invisible hands reached out of the walls and caressed him. Everything he touched became an extension of his own extremities.

All night long, as he swam through a corridor of silk, as the children and the servant girls slept. Süleyman arrived at the usual hour at Esma's room. They sat across from each other whispering because they knew of Iskender's sentience, that he could sense things in other rooms.

Iskender indeed heard them although he could not make out the words. Their poetry sounded to him like the seventeen-year locust falling from the sky he had heard in the Far East. He had journeyed to Isphahan from where he joined camel caravans to the distant reaches of the Silk Road, Samarkand, Tashkent, and Bohara, carryingThe Travels of Marco Polounder his arm, searching for clues on the origins of the Turkish civilizations. He had even dared cross the Takla Makan, the desert of irrevocable death dreaded by all travelers, journeying to Uygur -- thanks to his camels, possessing a secret knowledge of springs, who led him to mysterious sources of life-giving waters and eventually to the great wall of China. There he had been stricken by an ailment that made him delirious and he was treated with strange needles they stuck into his body, as well as opium, an affliction that accompanied him through the rest of his life.

At dawn, still awake, Iskender rose absently to the sound of prayer and looked out the window. Against the cool darkness of the obsidian, he saw the silhouette of a man gingerly ascending the invisible steps. So much poetry in that vision, but as a patriarch he had obligations. He could not allow the family to lose face.

Esma was kneeling down in prayer when she heard the firing -- three shots. She ran to the balcony. The smell was familiar to her, the smell of burning gunpowder seasoning the night. The smell of her father's factories. The smell of her childhood. Saltpeter and sulfur.

Who? Who? Who?She heard the golden owl. Her beloved's totem. A rifled silhouette barely discernible stood above the obsidian.No, dear God, no!Then, she saw Iskender descending. Pain filled her chest. All the doors to the outside closed. All expressions locked inside her. She passed out.

As the new day began, everything seemed normal on the surface. The peddlers barking, the girls waking up, the running boy Sükrü shoving coal into the furnace, Iskender at breakfast, feta and olives. Acayiquearriving. But instead of Süleyman, as it had been until that morning, Iskender ushered the young Doctor Eliksir into Esma's room. Somber.

A sheet was stretched across her bed to prevent the doctor from seeing her face. Through a hole in the sheet, he examined, his scythe-like fingers groping for her privates. A pelvic exploration by feel. Gonca's hand guiding to lessen the pain, he slid inside Esma, digging for evidence.

Esma wept and Gonca did, too, on the other side of the curtain.

The doctor shook his head. "You're misinformed," he told Iskender as he walked out the door. "There is no evidence of any misdeed. Your sister is a virtuous woman. Always has been."

The boys wanted to know why their teacher did not come. And why their mother remained in her room and why they would not be allowed to see her. Although Esma silenced her tears in her pillows in order to protect her sons, they could sense something pitiful.

Gonca fed them copious amounts of Turkish delight to lessen their loneliness. She cut their hair. Showed them how to fold paper boats, float them in the water, then set them on fire. Aladdin drew maps. Cadri wrote poems in careful calligraphy. Each sank into his own desert.

Iskender retreated to his room, closed off the curtains to sunlight, fed the coals until the embers whispered through an iridescent glow. Esma had buried her face in the pillows when he had tried to apologize. He knew she would refuse to come with him. He might never see her again. He squeezed into his amber pipe a black paste smelling like manure. He swallowed the smoke, sank deep into the velvet oblivion. In his hand, he clutched the handkerchief that Süleyman had dropped. Inside was an egg-shaped piece of amber. He held it to candlelight and saw a moth escaping its cocoon. The eye of the insect was still open, although the wings were folded back inside. How incredible to see something that existed so long ago arrested in the midst of metamorphosis!

Soon, he drifted off into a dream that even the quiet sobbing of his sister, directly above, could not disturb. It sounded like another siren's song, Esma's cries and whimpers. As if the imbat wind was filtering the voices of the lamenting Trojan women from the Dardanelles. The women who had lost their men. No song more beautiful than grief.

At dawn, Iskender left. He'd never smile again until a very old man.

Esma wept in her room for months. She wanted to die but could not endure the thought of abandoning her sons. Every soul must confront the lament of loss. This life is but the curse of our desires.

Gonca read spiderwebs; she read pebbles and coffee grains. "So much darkness in your heart," she told Esma, peering deep into her cup. "Azrael, the angel of death, is perched on your left shoulder like a vulture. You're trying to reach someone on the other side but it's not possible because that someone has not yet crossed to the other side. I see him walking on a bridge. I see an unexpected reunion. But I see worse things before that. Dark clouds over a burning sky. Oh, mistress, pray for the winds to stop. Pray."

The Ottoman Empire and Germany were defeated at the end of the Great War and with the signing of the Moudros armistice in 1918, the Allied forces began the occupation of Anatolia. They parceled off the glorious Empire -- the great lands stretching from the Caucasus to the Persian Gulf, from the Danube to the Nile. They invaded Istanbul. The British occupied Urfa and Antep and the East. The French claimed the province of Adana and the South. Italian units quartered the interior province of Konya and all the way down to Antalia. All that was left was an interior terrain.

On a gloomy day in May of 1919, Greece invaded Smyrna. A cyclone appeared in the sky, twisting the city's fate.

At this juncture, as the Ottoman parliament dissolved and the Sultan yielded to the wishes of the Allied forces, a voice resonated all across the nation, campaigning along the Black Sea, shouting,"Independence or Death,"a phrase which became an infectious slogan on everyone's lips. The people put all their hope in their new hero, the commander of the Lightning Army, the hero of Gallipoli. His name was Mustafa Kemal.

So came the Independence war. Everyone took to arms, even children and grandmothers. People who had lived together for hundreds of years, who had mingled so many seeds that it was impossible to tell them apart, suddenly turned mean. Turks, Armenians, Greeks, Albanians, Kurds, Jews, Rums. Foreseeing the future, many old and wealthy Levantine families left, taking their wealth. Whole armies were maddened by contaminated grain. Families were broken; brothers killed brothers (how could it be!); friends betrayed one another while Greek soldiers cruised the streets, deafened by the wailing of spirit voices.

The men were gone from Smyrna. Even the running boy Sükrü was no longer around to watch over the family. One day, shaving his head, he slung a sack across his broad shoulders, stopped for good-byes before going off to the front. Gonca and Ayse each wept privately. One for love, the other for lust.

With no one watching over them now, the women boarded me up from the inside. The girls kept vigil behind tightly closed lattices for bread and yogurt from black marketers, as the opportunists gnawed their way around town like hungry rodents, taking advantage of misfortune.

When a neighbor's maid was shot while hanging the laundry, Esma prohibited the boys from going on the roof terrace. They sneaked up anyway, to watch the ships with different flags in the harbor -- how could a boy resist such? A great orgy of colors splashed across the sky, crimson and black, like Gonca's paper ships they used to set aflame. Smell of gunpowder suffused the air, lingering, potent like the smell of skunk. Cannon shots in the distance. Shrapnel. Dead horses. Screams.

On one occasion, lowering a basket from the third-floor window to receive some provisions from a street peddler, Gonca was astonished to pull in a stewing chicken. She excitedly presented this rare commodity to her mistress.

They did not know who had sent it but since it was the boys' seventh birthday, Esma decided to make Circassian chicken to celebrate. They still had the last season's walnuts in the deep cellar. As she reached inside the thin carcass to pull out the entrails, her hands felt something hard and metallic. It was a key. How absurd. Why would someone put a key inside an emaciated chicken?

She washed the key and polished it. It was a well-crafted key.

"What will you do with it, Mistress?" Ayse asked Esma.

"I don't know." Yet a strange instinct made Esma keep the key though she did not know why. She put it in a mother-of-pearl box where she kept her hairpins on her dressing table.

The children were restless. They had now taken to playing underground where subterranean arteries, from the times the Greeks pirated the Aegean, meandered across the entire city. This humid darkness now belonged to the children of Smyrna. They hid inside the enormous cisterns, where once sacrifices had occurred, that had doubled as sewers since the Roman days. Rumors of hidden treasures enticed them immensely. But rumors of slimy prehistoric animals that lived in those oily waters kept them from wandering too far into those forbidden passages.

It was dark and damp and scary down there but secret and they could pull their pants down, show their "organs" to one another and sometimes even be daring enough to touch because it felt good to touch things in the dark.

They waited for the streetcars that made the walls shake as if suffering a seismic tremor and the sounds of the tracks groaned like a trapped Minotaur. Convinced that a giant beast was pursuing them, the children managed to work up hysteria, and with rampant adrenaline, plunged upstairs to find refuge under their mother's satin arms.

Two men arrived carrying a lovely walnut wardrobe that had miraculously survived the danger outside.

"But who has sent me this wardrobe?"

They told Esma that it was from her brother Iskender. They said he had found it in the city of Saffron where craftsmen excelled. Esma refused to believe them at first; it seemed incongruous that at such time of war and famine her brother would bother sending her a gift like this, even if it was to ask her forgiveness. People did not even have enough bread or coal.

But Gonca read their coffee grains and persuaded Esma to accept the enigmatic wardrobe. One should never turn down a gift. From the way they labored up the steps, it was obviously heavy. Esma asked them to open it but they said it was locked.

"What good is a locked wardrobe?" Ayse complained. "We can use it for firewood, I guess."

"We can't even find a locksmith at a time such as this."

But that became unnecessary. That night, as Esma kneeled on her rug praying for her dead lover, only one thought invaded her mind. She felt him so close that it was as though he was in the room, near her. She felt his presence. She could almost hear him whispering her name.

"Esma, Esma."

It was something between thrill and fear. The euphoria of incertitude.

"Esma, Esma," the voice repeated, erasing any doubt in her mind as to the identity of its owner. She had never seen a ghost but her mind was open.

"Süleyman!"

At first, it seemed to be coming from inside the walls or from the rustling of leaves outside but as her ears became attuned, she heard the tapping inside the wardrobe.

"The key," the voice whispered. "Please, hurry!"

"The key!" Trembling, Esma searched for the box. The key. There.

The key fit perfectly into the lock. She opened the wardrobe.

Instead of a transparent ectoplasm, Süleyman stepped out flesh and blood, dressed in a khaki uniform with brass buttons that glistened in the dark. He gasped for air.

"I've been in there for days, it seems, but I've lost all track of time. My senses are dulled."

Despite the fatigue that painted dark circles under his eyes, despite the gauntness from undernourishment, despite arthritic joints from the dampness of war, he exuded an unworldly radiance. Something had hardened his jaw, saddened his features, bridled his tongue but he was no ghost. He reached out and touched Esma's face.

"I thought my brother..."

"Only to warn me he would, if I showed my face to you again."

"I'd given you up to the holy martyrs," she began to cry. "Thank heaven you've appeared to me like one of the seven sleepers of Ephesus."

He removed his high-collared tunic, his astrakhan hat. His hair shaved like aMehmetcik,a Johnny Turk, a soldier of the armed forces, bitter fate for a pacifist. For anyone, really. Especially for Süleyman.

"I'll sacrifice the fattest sheep in Anatolia," she told him. "I'll protect you."

"No fat sheep left in Anatolia," he laughed ironically. "You don't know what a miracle it was to find even a chicken. But, please, give me something to eat, dear heart. My soul is about to leave my mouth."

The cellar smelled of warm milk and cinnamon. Gonca was stirringsalep,a warm pudding made from theOrchis mascularoot. When she saw Esma breeze into the kitchen, she sensed that something unusual ailed her mistress but kept quiet, fearing the words might spoil the spell. She watched Esma hastily gather things on a tray and run upstairs.

Süleyman voraciously gulped down the fermented root, devoured the dark bread. Later, she poured water from the copper pitcher for his ablutions. Starting from the right, working to the left, she washed his hands, his feet. He wiped her tears.

Blessed heaven. Oh, yes. That night, Süleyman was emanating a fervor as in the paintings of the Divine; flames poured out of his body, invigorating everything around him. The tingling in the air, the song of silence was even more alluring than the singing of the sirens. Contagious, it washed her all over. He reached out to Esma, consumed her with his gaze.

Esma and Süleyman forced themselves to sit down on the Louis Quinze couch like the old times, with distance between them. They were not to touch. They stared at the sky to calm themselves. This privileged them to witness a miracle. They saw something that night no one else had ever seen. They saw, instead of one, double moons in the sky. So it seemed. Saw them approach each other weaving through the fast moving clouds. Closer and closer they came, like the moons, their radiance increasing as they were enraptured in a constellation of unconsummated passions.

In her room, Gonca also saw the double moons. She knew it was an eclipse -- for her, an ominous sign. She smudged the boys' bedroom with juniper branches. To protect them from the evil eye, she lit a candle to Aesculapius, the heathen healing god, and let it burn till it expired.

Down on earth, Esma unrolled her prayer rug, though it was past the prayer time; she peeled off her clothes just like in thehamamand concealed her nakedness with a piano shawl before lying down on the rug and opening her legs away from the obsidian rock.

Süleyman bent his knees and touched his forehead to hers. Mutable like ever-changing colors of the sky, the patterns and colors of the shawl, the rug, the floor tiles inextricably blended, free of contours. They began moving at the speed of dark.

For hours and hours.

Never a greater blessing.

Never a more ardent prayer.

Knowing it was the last.

Before sunrise, Süleyman vanished.

From that day on, Esma surrendered herself to prayer. It was like she'd gone mad. Like other women who go crazy over war. All day long, bending her frail body up and down so much that she shrank into a skeleton, then began swelling like a starving child. In the mornings, she threw up. At night, out of exhaustion, she collapsed.

At dusk, when Gonca came to cover her, she felt her mistress's forehead for fever, counted her pulse, and thought to herself. "Oh, great Goddess. What shall we do?" She knew Esma was with child. She was certain, having midwifed theImam's daughter and other girls before. And, I knew as well, maintaining all pretense of peace while the war ravaged my skin. I tried to spare the ones inside me. I was well built, resilient.

Nightly, the Ferret, that old creep who had brought so much misery to Esma, prowled outside, milky eyes protruding from his fecent face like a predator circling his prey. He strained to hear the murmurs inside, contracted his nostrils, his eyes leaped out of their sockets into private interiors. He was like a disease, chrome yellow and mephitic. One time, he urinated on the outer walls, marking his territory. If I had tears, I'd cry. If I had a voice, I'd swear. If I had hands, I'd slay. As providence would have it though, the nightman caught him in the act and kicked him away from the wall with his staff. Beat him to the ground.Tap, tap. Slap, whap.

"Son of a whore. Shove off. Go piss on your mother, will you?"

It must have been around the same time when a soldier delivered a letter through the kissing window, a small opening for the delivery of messages. Scribbled on tar paper. "Promise, you won't utter a word to anyone, the apple of my eye," she told Cadri as she handed him the letter. "Read this to me. Read"

The boy read with easy fluency:

In the mountains, I carry orders. The earth, my bed. My roof the sky. You and the boys, my stars. Why must we? I ask each time I take a breath. Why must we? But when I return and we transcend all this, I know, and I know we'll find some bliss. My thoughts, my dreams are always with you, my love. You are my soul."

No signature. No need for one. The boy recognized the writing. "Why must we?" he asked, comprehending the gravity but unprepared for its consequences. "What happened to the egg with the cocoon inside?"

Cadri saw, for the first time, the tear-shaped diamonds falling off his mother's eyes and gathering into a pile on her lap, the diamonds that would save the family from being destitute, in the next few years when things became much worse.

But with all the devastation around her and the stirring in her belly, Esma knew she had to find a place of silence where the rumors of this damaged city could not harm her. Where she could be near her sister Mihriban. Where her sons and the girls could find some calm. Where she could give birth in the solitude of silk.

So, one day, they abandoned me.

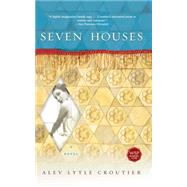

Copyright © 2002 by Alev Lytle Croutier

Excerpted from Seven Houses by Alev Lytle Croutier

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.