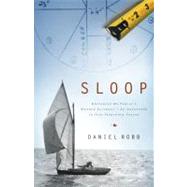

| Sloop | p. 1 |

| A Proposal | p. 7 |

| Perseverando | p. 9 |

| The Boat Mover | p. 15 |

| Bill and Rafe | p. 19 |

| Resolve | p. 29 |

| The Old House | p. 32 |

| A Start | p. 39 |

| January: Shed | p. 41 |

| Building a Shelter | p. 49 |

| Shed: Done | p. 53 |

| Consultation | p. 55 |

| Opiner | p. 64 |

| Description | p. 66 |

| Giff | p. 70 |

| Origins | p. 74 |

| February | p. 78 |

| The Quest for Wood | p. 86 |

| The Source | p. 98 |

| To Build a Steam Box | p. 102 |

| Kettle | p. 109 |

| The Auto Zone | p. 112 |

| Nine Miles by Water | p. 114 |

| March | p. 115 |

| September | p. 115 |

| Walden | p. 117 |

| November: Bending In a Frame with George | p. 127 |

| One Frame | p. 136 |

| Harbor Ice | p. 139 |

| Talisker | p. 144 |

| March | p. 156 |

| April | p. 159 |

| May | p. 161 |

| June | p. 162 |

| June 21 | p. 166 |

| The Planks | p. 169 |

| Mast Hoops | p. 173 |

| July: The Bulkhead Grille | p. 187 |

| First Thursday in July: Decks | p. 195 |

| Canvas Decks | p. 204 |

| Floorboards | p. 207 |

| Monday, Second Week of July: Transom | p. 209 |

| Second Thursday in August: Elf | p. 212 |

| Stories | p. 216 |

| Third Monday in August: Covering Boards | p. 222 |

| Story | p. 223 |

| Three Tillers | p. 225 |

| Third Tuesday in August: Seats | p. 227 |

| Third Wednesday in August | p. 230 |

| Third Thursday in August: Spars | p. 231 |

| Third Friday in August: Paint | p. 234 |

| Wednesday, Fourth Week in August: Bronze | p. 237 |

| Thursday, Last Week in August: Caulking | p. 240 |

| Friday, Fourth Week in August: Sails | p. 244 |

| Fourth Saturday in August: Bottom Paint | p. 246 |

| Last Monday in August: Launch | p. 250 |

| Launch Day Cont'd.: Pumping | p. 254 |

| Shakedown | p. 258 |

| Proposal | p. 266 |

| October | p. 275 |

| November | p. 284 |

| Glossary | p. 287 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 303 |

| Index | p. 305 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Continue with the shed I did, rolling into the lumberyard at 9 a.m. or so on Monday. Lenny was there at the gate. I lowered my window.

"Hey Lenny, what're you doing up so early?"

"Bah humbug," he said.

"Lenny," I said, "There's only a hundred and eighty-two shopping days til Christmas. You aware of that?"

"Not if they drop the bomb on us, guy," he said, smiling at me.

He had me there. All I could do was drive on. I bought three more bundles of twelve-foot strapping. I had a whole bundle to break and still have enough to make the struts. On the way out Lenny checked my receipt and made sure the punchout (a little paper silhouette of Batman, this time) fell on my lap.

"Thanks, Lenny," I said.

"Bah humbug," he said.

It was about 9:30 when I got back home and began the process of making struts, again, being careful to keep the strapping in the mild sun as I did this. I broke just one piece, and soon had the twelve struts I figured I'd need for the shed.

The next step was to cobble together a twenty-foot ridgepole, which I did by laying down two ten-foot pieces of old two-by-four, end to end, and scarfing them together with a couple of four-foot two-by-four cheeks. This made a twenty foot beam. Then I fished a couple of twelve-foot posts made up of doubled two-by-fours out of the lumber pile. I had used these in staging I'd built to shingle a house, and they had been lying around ever since. I stood these up plumb at either end of my rectangle of foundation timbers, and then held them there with a couple of two-by-four braces. This was rough carpentry at its finest.

Then I screwed the ridgepole to the upright posts, one end at a time, and I was ready to lay my prebent struts along the sides, bowed out, so they would come together along the ridge beam like the ribs of a whale along a backbone. Which I did, and screwed them on, and added horizontal bracing between the struts. Then I spread an old tarp folded long and thin along the top of the ridgepole to take care of rough edges that might puncture the plastic wrap, and I began to wrap the shed.

It took three passes, beginning at the bottom. Each layer was held on by a few staples, with the final pass draped over the ridge. Then I stapled two-inch-wide strips of old shingle onto the outside of the struts to hold the plastic securely.

And it held, and seemed to work. Time to get Bill over for a look.

Copyright © 2008 by Daniel Robb

12. Consultation

I called Bill as soon as I was done with the shed, which was at about four in the afternoon. He answered, sounding weary.

"Hello," he said.

"That Bill?" I asked.

"Yup," he said.

"Dan here. Wondering if I can get you over to look at this boat when you have a chance."

"How about now?" he asked.

"You sure?"

"I gotta get the heck out of here," he said. "I've been waiting for some epoxy to go off so I can get at it with a grinder and it ain't. Think I must have let the can freeze this winter. I dunno. But I've cut as many bungs as I can stand to cut while I wait."

"Well, now would be great," I said.

"I'll see you in a few," he said, and hung up.

That was remarkable. Although it is good, if you're a tradesman, to get out and look at somebody else's problems. I suppose it's good if you're anybody. Ten minutes later he was in the drive in his pickup, which was a Japanese two-wheel-drive manual shift with a logo on the door, "Mayhew Boatbuilders, Senegansett, MA," in narrow gold letters.

He strode up to the shed in the same clothes he'd been wearing the other day, produced an awl in his right hand, walked through the opening I'd left in the plastic, and jammed the spike into the bow of the boat.

"Stem's solid there," he said.

"No time for hand shaking, huh?" I said.

"Oh, sorry," he said, sticking out his hand, which I shook.

"Yeah, I needed to get out of the shop," he went on. "One of those days."

"Rafe driving you nuts?"

"No, not today. He's out on his own today, checking out a double-ender a guy in Woods Hole wants us to cold-mold for him."

He was referring here to a practice where one takes an older wooden boat, shores up the hull, and then encases it in two or more layers of thin strips of wood, the second layer running in direction counter to the first, with epoxy gluing it all together. This wood-epoxy shell is then finished off with gelcoat, which results in a wooden boat which feels like wood and looks like wood (on the inside, anyway) but which looks and acts like fiberglass on the outside. The hull is suddenly immaculate, maintenance free, and leak free. It also becomes a much stronger boat, all for the addition of a shell around the hull a half an inch thick.

"I didn't know you guys did a lot of that," I said.

"We don't do it much, but it isn't real hard, and it does seem to be a good way to go."

"What do you think of working with the glue?" I asked.

"It's not so bad, but talk to me in thirty years when I've grown my second head, then I'll tell you what I think," he said. "Both of us will. So let's see what we got here."

He walked all the way around the boat, stopping here and there to look at details and to poke his awl into the hull.

"The planks go all the way fore and aft on this side," he said. "That's good. And the stem is fine," he said, poking again into the piece of oak that formed the leading edge of the bow. "The planks are continuous on this side, too," he went on, as he completed his circle around the boat. "Good."

"Everything's a little dry, but that's okay," he said, continuing to walk around the boat, "and the planks aren't pulling away from the frames much. This piece here is just filler," he said, poking at a two-foot chunk of oak at the forward end of the keel that was clearly gonzo.

"That can come right off. Cut a new one, screw it right back on there, and fair it out," he said. "No problem."

"The deadwood," he went on, poking at the big slabs of oak that made up the keel between the hollow part of the hull and the lead at the very bottom, "looks good, too. You know, Dan, I've seen a lot worse. But I can see that some of these planks are coming away from the frames [Bill, like many boatbuilders,calls ribs "frames"], so I think you have at the very least a complete reframing and refastening project on your hands."

As he said this he poked his nose over the gunwale, and looked down into the bilge.

"Oh Lordy yes, look at that. Those frames are just about to dry up and blow away." He went on, "I tell you what, man. You're going to need to replace most of those frames, which means taking off this cap rail." As he said this he tapped the thin piece of mahogany that formed the "rail" of the boat, the rim around the edge of the cockpit. "You gotta do that so you can get at the tops of the frames. You're also going to have to cut the rivets which hold the bottoms of the frames to the floor timbers, and split those frames right out of there."

The floor timbers were trapezoids of oak held perpendicular to the top of the keel by long bronze bolts. At intervals of every ten inches or so along the spine of the boat down in the bilge there was a floor timber. A frame was riveted to each end of each timber (one on either side), and the frames then rose in graceful curves up to the gunwales of the boat, with the planks screwed to the frames and running horizontally. It was a simple, strong way to build a boat (sometimes called "carvelbuilt") and as Bill assessed the boat's structure it lost some of its mystery, and with that its ability to intimidate me.

"How do I get at the floor timbers?" I asked.

"Well, if I were you," he said, standing quiet now in a mote of sun with his arms crossed, "I'd take off her two bottom planks on both sides. They're going to need refastening anyway, and once they're off, you'll be able to get right in there and see what you need to do."

I took this in, seeing that taking off the bottom two planks on each side would indeed make things vastly easier, allowing me to reach into the bilge (where all the action was) from the outside ofDaphie. But it was also going to be weird, because once those four planks were off, the whole upper part of the boat would be supported only by the frames, without the skin of planks holding it together at the waist. This would be like seeing a person reduced to skeleton through the lower part of her abdomen, while she retained her torso and the rest of her body. But I would adjust to it. This was, after all, the only way to health forDaphie.

"One last question, Bill," I said. I actually had three.

"Yup," he said, and looked back at me with his eyes open wide.

"Would you replace the keel bolts?" This was a question I dreaded asking, as replacing the keel bolts could mean a huge investment of time: I would need to get new ones made, and then install them somehow under the floor timbers. The keel bolts held the heavy oak and lead keel to the rest of the boat, so they were critical components. As I asked this I had visions of lying crushed on the sand under the lead keel after it had fallen off the boat.

See, I knew that to replace the bolts I'd probably have to remove that lead keel (somehow) and then recast it, which would mean making a mold from the original, setting that mold into the sand on the beach, cutting up the old keel and then melting it in a kettle over a fire, pouring the old molten lead into the mold for the new keel, and hoping all went well. If I were still upright and breathing after that whole scenario, I'd still have to tap new holes for the new bolts in the new lead keel, and then reinstall the new 750-pound behemoth -- all of which process increased the possibility for disaster and mayhem.

River of Molten Lead Engulfs Coasta l Community: Amat eur Boat builder Imolated.

"No, I'd leave those bolts alone," he said. "You could take one out and have a look at it, but in my experience they're usually okay."

"Really?" I said.

"Yup."

Yahoo! This was hugely good news.

"What about the floor timbers?" I asked.

"They look okay," he said.

"Really?" That was two questions up, two down. I was very surprised by his answers, and was now beginning to hope for the trifecta.

"Yep," he said. "As Confucius said, 'If keel bolt ain't broke, not to fix.' Let's take a look at the transom."

I felt like a condemned man who'd been pardoned. And then Bill addressed my third question, all on his own. He walked to the stern of the boat and stood for a moment eyeballing the transom's wineglass shape. It was made of broad mahogany planks running side to side, and held together by long iron drifts, which are rods that go down through the panels. He dug his awl into one of the four black stripes that ran vertically down the transom, showing where the drifts were corroding within. A chunk of dusty black wood the size of a small stone came out of the first place he probed.

"Yep," he said. "That's fugly. This is what happens to all the ones made like that. Earlier ones are oak, and not fastened with iron, but they have other problems. It all came down to this wide transom they had to have. It keeps the length of the boat down, and keeps the boat wide, and it looks pretty without any cleats holding it together, but those damned drifts always corrode. You're going to want to do something about this sometime."

"Can I put it off ?" I asked.

"Sure you can. And I probably would if I were you, 'cause it's tough to replace. You've got to cut the edge of the new transom precisely to the angle at which the planks come back to meet it. But the angle of the planks changes constantly, so it's a bear to get it right.

"But," he went on, "your planks and transom are still solid along the outer edges. As long as you can keep the transom from decaying any further in the center, I'd leave it for now, 'cause the edges look good. It's still sturdy."

He probed a few more places, and then put his awl in the front pocket of his coat, and walked out of the shed.

"All right, enough boat. You got a cup of coffee?"

"Sure I do," I said. "Come on inside."

I gave him a cup of coffee, and he stretched out in the one decent chair in the house.

"This is an okay little place," he said. "When'd you pick this up?"

"Last year. Last place in town with a roof for less than a hundred grand."

"I don't doubt it," he said, looking around the one room.

"Has it got a bathroom?"

"Yeah, and a loft and another little bedroom. But it didn't have much left in the way of a roof when I got it."

"You know, you've got a nice old boat out there," he said. "I hope you can find the time to bring her back."

"I'd like to," I said. "Though I'm not quite sure why, beyond the obvious goal of saving a good old boat. That's what I'm trying to figure out."

"I know what you mean," he said.

I waited for him to say more, and when he didn't, I asked, "You having second thoughts about the career?"

"Well, no, not really," he said. "At this point it's kind of like breathing. But it's beginning to bother me that I can't have a client who's a fireman or a clerk. When my dad was starting out, he worked on everyone's boats -- lobstermen's, fishermen's, the fireman who kept a string of pots, the real estate guy who'd retired from the Coast Guard and had a catboat he'd take over to Tarps [Tarpaulin Cove]. You know, it was regular people along with wealthy folks. But it changed about five years after I got back from the service, around seventy-five. I still enjoy the boats, and the craft, you know, but the clientele has changed."

"That's a problem for me, too," I said.

"How so?"

"Well, I'm trying to write about this boat here, but it's not something most people will ever own. It's an MG, or an Austin Healey, not a common thing for people to have. It has a value now, but it's hard for me to define it. The why of the value."

"The why. Jesus H.," he said. "I guess I've stopped asking that question. Maybe I shouldn't have."

"And you've replaced it with?"

"I'm not sure. Maybe with the how, as in 'how to pay the kid's tuition'..." He trailed off here, seemed to be observing his boot, which he had propped on the little table that sat in front of the woodstove.

"So Rafey gave you an earful the other day, huh?" he said after a moment. "You got to him right after he'd read all about the bogs along the river in the paper, before he'd had a chance to let it out on anybody else."

"I didn't mind that from Rafe," I said. "I mean, why should he hold back if someone walks through the door and he's got something to say?"

"If you're Rafe," he said.

"If you're Rafe," I said. "Plus, he lives alone on a boat, no one to talk to out there."

"Not everyone feels the need to create personal sounding boards at every turn in the hall," said Bill.

"That's true," I said.

"I hope you didn't take it the wrong way," he said.

"Nah," I said. "Rafe's a friend."

"He's a good guy, all right," said Bill. "And he sure can cut a plank. Jesus, he cut a plank with the bevel right on it the other day. I only had to give it half a swipe with a plane and it tocked in there on the first try. Blew my mind for the hundredth time. He's a savant. I love him. Hey, I gotta get going. Thanks for the coffee. Let me know how it goes."

"Last two questions," I said, catching him as he sat up in the chair, prepared to stand.

"Okay," he said.

"What kind of wood am I getting for the frames?" I thought I knew the answer to this, but I wanted to see what he'd say.

"White oak, white oak, and only white oak," said Bill.

This was what I'd thought.

"But it's got to begreenwhite oak," he went on. "Not seasoned. You've got to be able to bend it, and it's got to be quartersawn, with the grain running straight out both ends. If it's been seasoned you'll snap half as many as you bend, and it'll never be as good," he said.

"Quartersawn?" I asked.

"Sawn so the grain is perpendicular to two sides, parallel to the other two. You gotta get the grain to stack up like pages in a magazine, so you can bend the wood, just like you roll a magazine up. If the grain ain't quartersawn, when you bend that frame it'll just snap on you."

"Where do you find that wood?" I asked.

He sat there for a moment, looking kind of tired. Then he said, "Well, I mill most of my own, so I'm not sure where you're going to find it, but that will be one of your new adventures. How's that strike you?"

As soon as I'd asked the question, I'd felt a wall descend between us, as if I had exhausted his goodwill, or the number of hints he was willing to give to the novice. Like a good mentor, he was going to make me earn the rest of my understanding.

"That strikes me fine," I said. "What do I owe you?"

"Don't worry about it. Maybe I'll call you to bend a frame for me sometime. I've got your number."

"Thanks, Bill."

"No worries."

And so he left.

And I felt better about the whole project. Bill had come and seen the boat, and felt it could be done. He had yanked the whole thing out of "pie in the sky" into something close to respectability. I, on the other hand, still needed to figure out why I was doing this, other than the obvious motives of a paycheck and another arrow in the quiver of my literary career, such as it was. I wasn't sure what I was trying to get at, through this pile of oak, lead, cedar, mahogany, bronze, iron, paint, varnish, and rot.

Copyright © 2008 by Daniel Robb

13. Opiner

I couldn't sleep the other night, and found myself immersed in the following:

There are a great many varieties of oak and most of them are very poor indeed for they soon rot. The true white oak is one of the best things that God gave us here in New England, and I will try to describe it because nearly every lumberman will attempt to palm something else off on you. He (for the white oak is very masculine) is not called white oak because the wood is white or light color, but because as you walk through the woods his bark has quite a light shade in contrast to the rest of the forest, and when the breeze lifts or turns the leaves, the undersides are quite light.... White oak is without doubt the best oak for the frames of small boats.

So wrote L. Francis Herreshoff, son of Nat, who like his father was a designer of boats. He drew the Rozinante that Bill and Rafe were hoping to build, and thePrudence,H-28,Ticonderoga,Diddikai, andMarco Polo, among others, and he knew his craft down to the dimension of the pintles. It was in hisSensible Cruising Designsthat I found these words again. It lay beneath some other books -- spine facing away -- at the top of the shelf under the steep stairs that lead to the loft. I pulled it off the shelf at about 2 a.m., when I couldn't sleep, wondered what it was, lit a kerosene lantern, opened the beat-up tome and was reminded of the man's strength as a writer. I lay reading on the old green Edwardian couch, the lantern hissing softly on the table next to me. There was no wind, and occasionally the donk of the bell buoy at the western end of the Hole came to me, stretching across the water, crossing the fens and lowland, to bump up against the window. Only on still nights can I hear that bell. Another passage:

IfH-28's design is only slightly changed, the whole balance may be thrown out. If you equip her with deadeyes, build her with sawn frames, or fill her virgin bilge with ballast, the birds will no longer carol over her, nor will the odors arising from the cabin make poetry, nor will your soul be fortified against a world of warlords, politicians, and fakers.

There we have L. Francis on the construction of his twenty-eight-foot ketch theH-28, which slept four and in a slightly scaled-up version is one of the more popular cruising boats ever drawn. In his words (perhaps) may be discerned some of his father's philosophy about boats, the why of his own boats, and so the why of the H-121/2 Here is another of his thoughts:

...as I stumble along the beach, making the fiddler crabs scurry for shelter, or see the squirt of a clam on ahead,a sense of contentment fills me. My dog, too, feels the joy of living as he bounds on ahead, starting up a flight of killdees or rock snipe, which wheel overhead, making a delicate pattern on the sky, coasting downwind on curved pinions. As I sit on a rock and give thanks for these blessings which are freely given to all who will see them, the H-28 comes in view at her mooring, and as her white form is silhouetted against the opposite shore she seems beyond the realm of mere things -- a mythical dream come true, the answer to a sailor's prayers.

Amen.

Donk. The bell buoy's bell reaches across the water, and Ted, my cat, jumps up on the couch, wonders why I'm up at 2:30 a.m., butts her head into my knee. Yes, Ted, why are we up?

Copyright © 2008 by Daniel Robb

Excerpted from Sloop: Restoring My Family's Wooden Sailboat: an Adventure in Old-Fashioned Values by Daniel Robb

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.