What is included with this book?

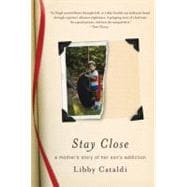

LIBBY CATALDI holds a doctorate in education and has been an educator all her life, most recently as head of Maryland's Calverton School. She has two sons, Jeff and Jeremy Bratton, and divides her time between Annapolis, Maryland and Florence, Italy.

| Prologue: If Love Were the Answer | p. 1 |

| The Boy in the Cape and Cowboy Boots | p. 5 |

| The Three Acts of the Worst Christmas Ever | p. 45 |

| Starting Down the Rehab Road | p. 64 |

| The Mothers in Al-Anon | p. 84 |

| Doing the Next Right Thing | p. 98 |

| The Functional Addict | p. 109 |

| Trusting Lies | p. 121 |

| The Double Life of My Chameleon Son | p. 136 |

| What Happened in New York | p. 151 |

| ôOur Family Is So Fucked Upö | p. 181 |

| The Gravity of Roller Coasters | p. 201 |

| Stagli Vicino, Stay Close to Him | p. 225 |

| Choices: Mine and Jeff's | p. 244 |

| Never Giving Up Hope | p. 268 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 289 |

| Afterword | p. 291 |

| Resources and References | p. 305 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.