The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Something is rotten in the state of modern marriage: it's the common expectation that wives should be superior. Wives are supposed to do all, know all, fix all.

Take this regular exchange I have with my husband of several decades. While I'm putting away groceries or cooking dinner or doing laundry, or all three at once, I'll ask him to let the dog out.

"I have to do everything!" he'll answer, in a testy, melodramatic huff, as he reluctantly gets up from the living room couch to open the front door.

The joke is, of course, that I'm the one who does nearly everything, but he pretends to get upset if he has to do one tiny thing. There are several layers of meaning embedded in his banter. First, he's making fun of himself for being upset. Second, he's admitting that he doesn't do anything. Third, he's acknowledging that I am the one who does everything. Finally, he's apologizing for the situation but confessing that there's nothing he can do about it.

All in one brief punch line.

It's no secret that in our family I'm the one who takes on more responsibility. I do more tasks, I oversee more of the daily business of living, and I also work full-time. I'm the head of our family unit: he's one of my minions. In our marriage, for example, I am the only one who can cook a turkey and make mashed potatoes. I am the one who can bake a birthday cake, from scratch or from a mix. And I am the one who knows how to get a coffee stain out of a shirt and where we keep the good glue. I'm also the one who knows how to replace the fill valve and flapper in the toilet tank so it will flush properly. I know how to restore Windows on our home computer, how to troubleshoot the satellite television system, how to repair the wireless Internet connection, and how to load the iPod. I research, plan, and arrange our family vacations; I pack the suitcases. I help our children decide where to apply to college, how to write the applications, and what to look for when we visit the schools. I hire the painters, the driveway repavers, the siding guys. I buy new sheets and pillows and bath mats, and I clean the carpet and comforter after every dog accident. I organize family gettogethers on major holidays, and I arrange dinners and movie dates with our friends.

My husband follows my lead, quite willingly, but he has no desire to be in charge. Going to work every day, washing two cars every week (even in winter!), and handling the family finances are the only jobs that he has signed up for. So, in his mind, every other family task is mine. Not long ago I planned a four-day celebration for our daughter's college graduation, one that was attended by our entire extended family. During our stay in Washington, D.C., an unfamiliar city, I asked my husband to pick up a cake from a nearby bakery. He was unenthusiastic, protesting loudly that he should not be the one to have to do this errand.

"I don't want to have to think," he declared, as if this were the perfect reason for not doing something he doesn't want to do. The implication, of course, is that I'm the one who's supposed to do all the family thinking. I think, therefore he doesn't have to.

With this attitude, it's no wonder that if I were hit by a truck tomorrow, he'd need lots of help to get by.

The truth of the matter is that I am not unique, nor am I alone. It turns out that a majority of married couples -- about two out of three -- are just like us: the wife is the one who can't get hit by a truck. She's the one who develops expertise in nearly all aspects of modern life; she becomes the de facto master of the marital domain while also earning a significant part of the family income. It's as if by taking on a husband, a wife gains a dependent -- not quite a child, but not quite a true partner either. She's Marge Simpson to her husband's Homer. This arrangement does not characterize every single married couple, of course, just a great many of them. While husbands may joke about wives being their "better half," quite often it's the literal truth. Wives are the better half -- the ones who are capable and responsible, organized and efficient, caring and involved.

I don't mean to say that wives think of themselves as superior beings: they do not. Most would never, ever call themselves better or more mature or more capable than their husbands, even if they are. Instead they might view themselves as the family manager. They might concede that they give more to the marriage. They might view themselves as being in charge. But few would ever use a word like superior, because it implies dominion over their mate. Also because it sounds snobbish and condescending and bitchy. And the bitch factor -- the fear of being perceived as mean and nasty and fearsome -- is what keeps superior wives from admitting their status. No wife wants to be seen as a bitch on wheels, as the Wicked Witch of the West, as the Cruella de Vil of the neighborhood.

The superiority of wives has become the only remaining fact of modern life that dare not speak its name.

We've come a long way since the early 1980s, a time when there was serious speculation that women suffered from a secret fear of independence. This was the premise of a bestselling book called The Cinderella Complex, which held that almost all women long for and need to be cared for by a man on a permanent basis. Today that notion seems quaint, even absurd, like a bad joke. The theory that women furtively yearn to be swept off their feet, adored, and treated like a princess seems as alien to many superior wives as the idea of opening a restaurant on Mars or living in an igloo. While some contemporary wives may harbor this kind of retro longing, few expect such wishes to be fulfilled, even if only for a few days or weeks out of the year.

Indeed, the cultural mood had shifted so drastically by the end of the 1980s that fiercely independent working wives -- and not secret Cinderellas -- had become the focus of attention in American domestic life. Suddenly the mass of working women, far from being afraid of freedom, were wallowing in it. They were the ones working for pay all day, then returning home to do domestic work all night. Because couples devalued women's paid work, many of them assumed women should be responsible for child care and domestic chores, according to Arlie Hochschild, who wrote The Second Shift in 1989. Women were victims of a "stalled revolution," she said, trapped in the old role of unpaid domestic servant while also leaping into a new one, of paid employee. They were leaders of a work/family revolution, but their husbands were sleeping through the bugle call to action. And in those days, most families considered the husband to be the head of the household, even if he had a working wife. While many men began to feel social pressure to do more at home, few responded in a meaningful fashion.

Today superior wives are still stuck in the same prerevolutionary rut. They continue to work the second shift, only now they're doing even more. They're doing everything, and doing it better too. While second-shift wives put in more hours of work at home, superior wives do that and more. They run and manage their family, often because they have no other choice. Beyond second-shifters, they're expected to do all, be all, and know all, but with little or no credit for their sizeable effort. As a result, their superiority is often invisible, shrouded in silence and secrecy.

The recipe for concocting a modern superior wife is simple. First, take a husband who tries to do as little as possible, one who may even fake incompetence to avoid responsibility. Second, add a wife who steps into the breach and uses her natural ability to master most aspects of adult and family life. And third, stir in the complicity of both: a husband who avoids domestic effort, worry, and stress, and a wife who allows her husband to be an unequal partner. Let the mixture simmer, and eventually the result will be a marriage that includes a superior wife.

I'm not just saying this because my own marriage ended up this way: I've got solid, scientific proof that it's true. The Web research I conducted over the past few years provides strong and incontrovertible evidence that the superior wife syndrome is real. My research consists of several original surveys that I designed, posted on the Internet, and analyzed statistically, which I'll describe in detail in chapter 1. Using these surveys, I studied 1,529 wives and husbands from across the country and around the world. The wives and husbands who answered were mostly Americans and came from all fifty states. I heard from a husband in Hilo, Hawaii, and a wife in Kasilof, Alaska. My research included at least one wife from Delray Beach, Florida, and another from Athens, Georgia; one from Bismarck, North Dakota, and another from Cheyenne, Wyoming; and several from East Brunswick, New Jersey. I heard from husbands in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Houston, Texas, and Carlsbad, New Mexico. Although my focus is mainly on superior wives in the United States, I also heard from Englishspeaking spouses around the world. I had responses from wives in Istanbul, Turkey; Sydney, Australia; Bournemouth, England; and Bayamón, Puerto Rico; I heard from husbands in Davao, Philippines; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Chiang Mai, Thailand; and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

In addition I conducted personal interviews with a large number of married women and men. I quote from them extensively here, both their written answers and what they told me on the telephone or in person. I've changed their names and some identifying details, since I promised them anonymity, although I've used their comments almost verbatim. I also pored over the latest social science research about marriage and relationships, divorce and femininity, household chores and dual-earner couples. All my research leads me to conclude that superior wives have emerged as the heads of the household, they make most of the family decisions, and they handle most of the family management tasks.

Indeed, when wives describe their situation, they use the word everything constantly. It's as if "everything" is their one-word motto: "I do everything" and "Everything is what I do" and "I have the most responsibility for everything."

Adelina, for instance, is a thirty-one-year-old office manager and mother of one from San Jose, California. She and her husband, Frank, work fulltime, and both earn about the same amount. Here's how she describes her role in the family: "I do all of the financial planning, the long-term investing, the registering for work benefits at enrollment time, and the balancing of the checking account. Anything paperwork-related is me. I also do most of the clothes shopping, grocery shopping, and household shopping. I handle everything related to our daughter's school, her doctor visits, her friends. I handle our family calendar, I plan parties, I take care of correspondence. Frank calls me the CEO." There is, however, one thing that Adelina never does: "I don't take out the trash, ever."

Adelina could accurately describe her job in life as "Everything but the trash."

Although a majority of marriages may contain wives like Adelina, who are married to husbands like Frank, I am not saying that the male gender is comprehensively incompetent, nor am I taking a man-hating stance here. What I am saying is that after being married for a while, and especially after having children, a large number of husbands deliberately surrender family concerns and responsibilities and begin to expect their wives to take charge. And in many marriages, that assignment eventually includes nearly everything. It's as if husbands raise the art of oblivion to new heights; they can fiddle while wives burn through most of the tasks of adult life.

Some wives claim that they have taken control of family life because "it seems like I have no choice, it's just a natural occurrence," as a fortytwo-year-old woman puts it. Others confess to being impressed that their husbands are able to function in the world at all, without their constant intervention. "I'm amazed he's still alive," says one such wife.

I don't believe that there are rigid gender differences that cause this phenomenon, although it's true that women have several biologically based advantages when it comes to being able to manage at work and to care for a family at home. (I'll provide evidence for this statement in chapter 2.) Instead, I think the process is insidious; responsibilities shift over time, until both partners simply accept the wife's superiority as a natural state of affairs. The husband of a superior wife has it easy, so why rock the marital boat if she has already agreed to do the rowing?

Another reason for the proliferation of the superiority syndrome is a growing sense of confusion about the definitions of masculinity and femininity, especially on the part of husbands. Wives have grown used to the idea that being feminine means being sensitive and caring, but now it also means being ambitious and strong. They are able to think and behave like a loving mother at home, yet act like a cutthroat competitor at work. Their notions about femininity have adapted to the era in which they live, and to their family and work situation. But it's much more difficult for men to separate their sense of masculinity into different compartments. They see a masculine man as one who is aggressive and competitive and strong, not as one who is nurturing, warm, and self-sacrificing. If he can earn a good living, a manly man can't also roast a chicken and soothe a screaming toddler. Some husbands simply can't reconcile two such dramatically different ways of being; it's too confusing for their one-track minds to deal with. (Yet there are rare exceptions to this rule, like Intersex husbands, as we'll see in chapter 7.)

In any given couple, then, the husband is more likely than the wife to be the one who is oblivious to the needs of others. He is the one who sees the world mainly from his own point of view. He won't visit a doctor until his wife makes the appointment. He is incapable of buying the children new shoes unless she makes him a list, one that includes sizes and color preferences. He won't accompany the family to see a movie unless she asks the children what they want to see, checks the movie schedule, arranges to buy the tickets, gets everybody ready, and announces their imminent departure. He is perfectly content to sit and watch football or basketball or baseball or ice hockey on television while family activity hums all around him, as oblivious as if he were sitting on the bottom of the ocean floor.

In marriages that include a superior wife, the husband also tends to revel in his aura of ignorance. He may not know how to cook a decent meal, but he brags about how well he can grill a premade hamburger or a previously marinated chicken breast. He may be unable to calm a cranky infant or to shop for his children's clothing, but he'll insist that that's because his wife knows how to do this stuff better. He may not be able to balance a checkbook or pay the monthly bills, but he believes that his wife has more free time to do such chores. He can't organize a dinner party or keep track of his own siblings' birthdays either, but he thinks that's not his job. And doing the weekly grocery shopping after putting in a full day of work is simply too much for him.

After all, a superior wife can manage all this just fine, so why shouldn't she?

In addition, a husband with a superior wife can't do more than one thing at a time. He can't chop carrots and keep track of a toddler; he can't organize the tax information while helping an eight-year-old with an art project. He can't watch a baseball game and also discuss the family's upcoming vacation. He'll get upset and angry if forced to multitask; it makes him irritable and resentful, which is why he tends to freeze during emergencies: there's too much to do all at once. In some ways, though, it's not his fault, because it turns out that men are not biologically equipped to do several things at once, as we'll see in chapter 2.

A superior wife, then, is left to deal with the broken furnace or the projectile-vomiting toddler. It is the superior wife who ends up doing two or three or four things at a time, usually because she must. She steps into the competence breach, cooking and supervising and shopping and organizing family life, while also holding down a job.

A superior wife's life is one big, supersized multitask.

Even when both partners work outside the home, it is quite often the husband who feels exempt from doing anything other than delivering the paycheck. It's as if nothing but the job is his job, the way it would be in a traditional marriage if his wife were a homemaker. It doesn't seem to matter if she works twenty or thirty or fifty-five hours a week. Even if the couple assumed they would share everything after they were married, they often abandon that assumption when life gets complicated by children and home owning and life managing. What were once their responsibilities become her responsibilities, and that's a very long list.

Take Sue, a New Yorker who at forty-five has been married to Bill for twenty years. Sue, who worked before she and Bill were parents, took only a brief maternity leave after each of their two daughters was born. Sue has always planned all the meals, cared for the children, paid the bills, arranged the vacations, organized the medical and dental care, figured out the social life, managed the household, and earned most of their income. Where she leads, Bill happily follows, she says.

This leaves Sue with a certain lack of respect for her husband, a man who is less than a partner, someone who "can't cope in an emergency. He freezes up, like he's terrified, and he can't even think or speak." Worse, he seems unable to manage even the most basic tasks. Sue explains, "My favorite is, he'll tie up the garbage and then he'll say, 'Can you take it out?' "

Sue has taken fond care of Bill, as if he were a large and balding third child, for decades, and that's what he's come to expect from her. If Sue dropped dead, she says, "My husband could probably not survive without me. And I'm pretty sure he'd live on pizza, take-out Chinese, and food in cans."

Many superior wives imagine the same if-I-dropped-dead scenario, usually with disastrous consequences for their clueless husbands, who would need to be on the market for another superior wife, and pronto.

Sherry, forty-two, a mother of two, can't imagine what her husband would do without her. She tells me that in her next life, "I want to come back as my husband, because his life never changes, no matter what happens." She does everything, she says, while he waits around to be told what to do and where to go. He expects her to take care of him, and she does. If she vanished from his life, she'd need to clone herself first.

Marge, thirty-nine, is a working wife from Connecticut who is also her husband's knight in shining armor. She says that she and her husband, a workaholic dentist who is rarely home, reached an agreement early on in their marriage. "I do everything inside, he does everything outside," she says. Because they live in the northern hemisphere and not in a palm-frond hut in Tonga, where life is lived outdoors, this means that she does the cooking and laundry, the child care and the pet care, the social arranging and the cleaning. He does the gardening, mostly because that's his hobby and that's the only chore he really wants to do. He considers this a fair deal. She considers it her lot in life.

Sandra, a twenty-nine-year-old newlywed from Great Britain, senses that her husband "feels better than me, because he earns so much and I don't earn anything." That's why "he never lifts a finger at home," she adds, despite the fact that she's in school to earn a graduate degree in counseling. Sandra has figured out that if she wants to get her husband to do anything other than work and sleep and eat, "I have to smile and ask him if he wouldn't mind doing it. But he usually forgets I asked. He'd rather go to the dentist than do anything that's helpful at home."

Finally there's Cindy, forty, who lives on Long Island in New York and works part-time as a physical therapist. She doesn't think her husband could manage without her, unless he found a replacement wife. Cindy expresses a nostalgic longing to be taken care of by her husband, only once a year, on their anniversary. But even then, she's the one who has to plan that special night, because, she says, her husband is "out to lunch" when he comes home from work and isn't capable of making such arrangements without her help. It's as if, she claims, his brain stops functioning the moment he leaves his New York City office.

All these wives agree that "what we're doing is keeping the world functioning."

Wives like these insist, whether they work for pay full-time, part-time, or not at all, that it's only through their efforts that their family stays together. This situation no longer disturbs or troubles most of them, simply because it seems inevitable, the way it has been since they said "I do" and will remain, at least until they say "I won't."

While I'd like to claim credit for the idea that women, or wives, may be superior to men, it's not a new one. Four hundred years ago, an Italian noblewoman, Moderata Fonte, wrote The Worth of Women, in which she stated that women would be much better off, in every way, if they could live "without the company of men."

More recently, the Baltimore journalist H. L. Mencken wrote a book titled In Defense of Women, in which he explained the many reasons that women are better and smarter than men. He stated that "complete masculinity and stupidity are often indistinguishable" and claimed that women are much more perceptive and intuitive and intelligent than men, which, at the time, was probably a much more shocking and radical proclamation than it is now.

Half a century ago, the anthropologist Ashley Montagu also expressed the view that women are naturally superior to men. He proposed a revolutionary idea for the time, that college-educated wives were wasting their lives as homemakers and that it was foolish for them to be subservient to their husbands. "It is the function of women to teach men how to be human," he wrote.

My premise is similar, although I do not believe that women and men should live apart or that innate gender differences are an insurmountable problem. Instead I am proposing that the person in the husband role, usually a man, often exploits the one who is in the wife role, usually a woman. He will try to get away with doing and thinking and planning as little as possible, simply because he can. When he does, the person in the wife role takes over. Because women are better than men at many aspects of life crucial to a family's well-being, they are the ones who tend to end up as the more accomplished and the more efficient member of the marital union. Being accomplished is a woman's default mode.

Some husbands, though not all, are willing to admit that this has happened in their own marriage. Gerry, thirty-nine, confesses that his wife is superior in many ways but that this is to his benefit. "Because she's in charge, I don't have to be," Gerry says, quite happy and relatively unembarrassed about coasting through his married life.

Gerry eased himself into incompetence, he says, by not trying very hard, so that his wife does whatever he prefers not to do -- which is a lot. But Gerry's conscious and deliberate inferiority strategy is highly unusual. More often, husbandly inferiority is not premeditated, it just seems to happen. It occurs when a husband tells his wife, "You do the dishes so much faster than I do," and so she does. Or when he admits, "I can't change the sheets by myself," and so never does. Or when he confesses that he doesn't feel clearheaded enough to pay the bills, and so she does. It's not that she thinks she does all of this better than he does; it's just that he wheedles his way out of being responsible, and she steps in to fill the vacuum.

This book will explore how the superior wife scenario arises. In chapter 1 I will define and describe the phenomenon and explain how I came to these conclusions. In chapter 2 I'll delve into the biological and social and psychological reasons for the existence of superior wives and describe how women's innate advantages make it relatively easy to fall into the trap of self-denying superiority. Wives are equipped with a biological advantage that makes them more empathic and gives them the ability to multitask. In addition they are saddled with dual social expectations, that they should be in charge of the family but that they should also work for pay. Women are also blessed with a psychological need to please others, no matter what. Thus, this triple-headed female blessing -- of biology, culture, and psychology -- acts as the catalyst that propels wives onto the path of superiority.

I'll also discuss, in chapter 3, the differences among wives' work situations as a function of the proportion of the family's income they earn. There are four types of wives, based on their monetary contribution to the marriage and family: the Captain and Mate wife, who stays at home while her husband earns the money; the Booster wife, who earns some of the family income; the Even-Steven wife, who earns about the same as her husband; and the Alpha wife, who earns all or nearly all of the family income. No one type of wife is more likely than any other to be superior; as we will see, wifely superiority is not based on who earns more money or who spends more time at home.

In addition, many couples don't see eye to eye about whether the wife is the superior one. When I mentioned the title of my book to several men, one responded that it would obviously be "a work of fiction." Another said that it was probably going to be "some kind of pamphlet." Neither of these men, by the way, has ever been married. But even married men are resistant to the idea that their wives may be much better than they themselves at modern domestic life. Their wives would say that the men say that because they are completely oblivious to what's going on, which their husbands emphatically deny. But if the men truly are unaware, then that's what they would say, no? Chapter 4 delves into the superior wife situation from the husband's point of view, exploring the reasons for male obliviousness. It also presents an encyclopedia of nagging, summarizing husbands' views and commentary on what their wives nag them about, from "A, Appearance" to "Z, Zoning Out," and everything in between.

In chapter 5, I look at the situation from the female point of view. As it turns out, superior wives are less happy about their lives than other wives, and they're more likely to believe that their marriage might have been a mistake. Half of them admit too that they are the family's "primary nagger," and they confess to their own nagging habits. They also comment on their husbands' favorite topics for nagging, which are not all that different from their own. Marital nagging hot spots, for wives and husbands, include laundry and socks, dishes and television, video games and money, money, money.

A great deal of marital nagging also revolves around the most incendiary topic in modern life, sex. Some wives make a habit of refusing sex; most husbands are the sexual initiators. In some marriages, however, the reverse is true, and wives initiate and husbands refuse. I explore both situations, as well as the top ten sex wishes of wives and husbands, which are more similar than you might expect. I also reveal the four types of married sex: Duty Sex, Old Shoe Sex, Hot Sex, and No Sex. The groups are not mutually exclusive, so you could have Old Shoe Sex, say, for years, and then suddenly tip over into Hot Sex. Still, many couples find themselves in one group or another most of the time. Chapter 6 will examine the ways in which a wife's superiority affects her sexuality.

Finally, as I've mentioned, not all marriages include a superior wife. I've examined nonsuperior wives and their husbands in great detail, using statistical methods, and in chapter 7 I explain how these couples manage to escape the superior wife trap. Somewhat surprisingly, these couples are either supertraditional or extremely egalitarian, at one extreme or the other. When partners are in agreement about how the marriage should be arranged, there's a better likelihood they'll be in a nonsuperior union. Wives in traditional marriages believe that the husband is the unequivocal head of the household, and thus they reject superiority out of hand. They tend to have mates I call Caveman husbands. Wives in egalitarian marriages have husbands who are truly committed to equality; they have a Team Player husband or an Intersex husband. Nonsuperior wives accept imperfection, and they don't need to have everything done their way all the time. They use an as-if operating system, which means they function as if they are not able to do all and be all for everybody, always.

Women who have already fallen into the superior wife life need not despair, however. In chapter 8, I advise wives on how to create a new and more perfect nonsuperior wife union. The key is to convince their husband of the importance of this step, to work on ridding themselves of their old habits, and to rehabilitate the marriage, as a team effort. I offer twenty-one suggestions and tips for how to do this. Making this change won't be easy and it won't be quick, but you can do it if you want it badly enough and if you can convince your husband that change is in his best interests too. The aim for wives is to lead a marriage rebellion, by redefining and reinventing modern marriage. They must strive to reshape their twentieth-century union by creating a new and improved conjugal partnership, one that includes not one but two "wives" in each marriage.

First, however, it's crucial to figure out what kind of marriage you yourself are in. Are you a superior wife? Or are you married to one? Here are a few signs that your marriage may be one that includes a superior wife.

In your marriage, does the wife

In your marriage, does the husband

If you answered yes to at least six in each of these two groups of questions, you may be a superior wife -- or married to one. If so, then this book is your ticket for a tour aboard the good ship Wifely Superiority, with detailed instructions on how to disembark. It will explain why wives become superior, how their superiority works in the family, and how such wives and their husbands view their situation. It will reveal the many consequences of wifely superiority, describing the ways in which that situation harms the marriage, damages a woman's sense of self, and leads to long-lasting disappointment and unhappiness. Finally, this book will reveal several ways in which superior wives can ditch their superiority and transform their marriage into a mutually beneficial union.

There's no time to waste, so get on board. You've got nothing to lose -- except your superiority.

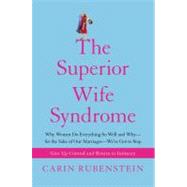

Copyright © 2009 by Carin Rubenstein