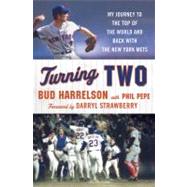

BUD HARRELSON played in the Major Leagues from 1965 to 1980 and retired second on the all-time list of games played for the New York Mets. He was a member of the Mets coaching staff from 1985 to 1990 and served as Mets manager in 1990 and 1991. He lives in Long Island and is co-owner and senior vice president for baseball operations for the Long Island Ducks, a team in the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball. Harrelson was inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame in 1986.

PHIL PEPE has reported on sports in New York for more than five decades and has authored more than fifty books, most of them on baseball.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.