Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

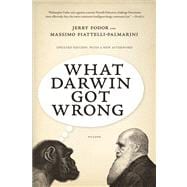

Jerry Fodor is a professor of philosophy and cognitive science at Rutgers University.

Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini started his academic career as a biophysicist and molecular biologist and is now a professor of cognitive science at the University of Arizona.

| Acknowledgements | p. xiv |

| Terms of engagement | p. xv |

| What kind of theory is the theory of natural selection? | p. 1 |

| The Biological Argument | p. 17 |

| Internal constraints: what the new biology tells us | p. 19 |

| Whole genomes, networks, modules and other complexities | p. 40 |

| Many constraints, many environments | p. 57 |

| The return of the laws of form | p. 72 |

| The Conceptual Situation | p. 93 |

| Many are called but few are chosen: the problem of 'selection-for' | p. 95 |

| No exit? Some responses to the problem of 'selection-for' | p. 117 |

| Did the dodo lose its ecological niche? Or was it the other way around? | p. 139 |

| Summary and postlude | p. 153 |

| Afterword and reply to the critics | p. 165 |

| Appendix | p. 191 |

| Notes | p. 207 |

| References | p. 251 |

| Index | p. 277 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

the fixation of the phenotypes, or for both of these reasons.