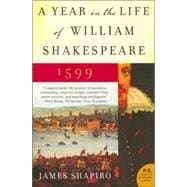

1599 was an epochal year for Shakespeare and England

Shakespeare wrote four of his most famous plays: Henry the Fifth, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, and, most remarkably, Hamlet; Elizabethans sent off an army to crush an Irish rebellion, weathered an Armada threat from Spain, gambled on a fledgling East India Company, and waited to see who would succeed their aging and childless queen.

James Shapiro illuminates both Shakespeare’s staggering achievement and what Elizabethans experienced in the course of 1599, bringing together the news and the intrigue of the times with a wonderful evocation of how Shakespeare worked as an actor, businessman, and playwright. The result is an exceptionally immediate and gripping account of an inspiring moment in history.

“Mr. Shapiro has given us by his encyclopedic scholarship and lucid narrative a hitherto unknown Shakespeare.” -Jacques Barzun, author of From Dawn to Decadence

“an unforgettable illumination of a crucial moment in the life of our greatest writer.” -Robert McCrum, The Observer

“Shapiro’s scrupulous scholarship has given us a Shakespeare both for his time and our own.” -David Scott Kastan, General Editor, The Arden Shakespeare

“This is one of the few genuinely original biographies of Shakespeare.” -Jonathan Bate, Sunday Telegraph