Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

CHAPTER ONE

Spring 1995: Rural Virginia

I climb up on the loading platform in back of the small country hardware store somewhere off Route 13 near Nassawadox on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. I am looking for the proprietor. The air is cool in the shadows of the storeroom and redolent of fresh-sawn lumber. I hear voices behind me. The proprietor, middle-aged with skin leathered by the sun, is talking to two young white men in bib overalls. The young white men are leaning on a rusting 1962 Ford station wagon of indeterminate color. From the shadows of the storeroom, I move in their direction.

"A boy jus went in theah lookin fuh ya," one of the young men says to the proprietor.

It is two months before my fifty-fourth birthday. Twenty-five years have passed since I graduated from Harvard Law School. I have conferred with presidents and more than once altered the course of American foreign policy.

The "boy" to whom the semiliterate corn farmer is referring is I. And I have traveled a long way to nowhere.

My rage is complicated by the balm of comparative material success. I tell myself that I cannot be wounded by a red-faced hayseed. But I am. The child lives on in the man until death.

My father died in 1974 at the age of sixty-eight, of what the family now believes to have been Alzheimer's disease. Toward the end, and not lucid, he slapped a nurse, telling her not to "put her white hands on him." His illness had afforded him a final brief honesty. I was perversely pleased when told the story.

From slavery, we have sublimated our feelings about white people. We have fought for our rights while hiding our feelings toward whites who tenaciously denied us those fights. We have even, I suspect, hidden those feelings from ourselves. It is how we have survived.

Well-educated blacks have even been inculcated with the upper-stratum white distaste for excessive emotionalism. Black folk of my time talk about white people and their predilections at least once daily but never talk about or with anger. It seems unnatural. Where have we stored the pain and at what price?

The anger caroms around in our psyches like jagged stones. Hidden deep anger. We don't acknowledge it. We don't direct or aim it. But it is there.

Spin the cannon. When it points threateningly outward, even white liberals dismiss us to a perimeter of irrelevance or worse. When it points inward, white conservatives find in our self-hate praiseworthiness.

Best we just stow the cannon, hide the anger, and do the best we can. Without contemplation, this is the deal most of us are constrained to accept. A Nat Turner doesn't make it in America, but a Clarence Thomas frequently does.

Winter 1967: Cambridge, Massachusetts

I have arrived from segregationist Virginia to attend Harvard Law School. Our first-year class of more than five hundred students is divided into four sections. My section is sitting through a torts lecture given by young professor Charles Fried. Tall and bespectacled, Professor Fried was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1935, was educated at Princeton and Oxford and Columbia, and will become Solicitor General of the United States under President Ronald Reagan.

With what seems to me affected formality, Professor Fried is holding forth from the well of the Austin lecture hall on the notion of nuisance as an actionable tort. Among the listeners are five black students, including Henry Sanders of Bay Minette, Alabama, who will become an Alabama state senator, and Rudolph Pierce of Boston, who will become a Massachusetts judge. There are one hundred and twenty-one white students in the large hall. Seated halfway up the ascending bowl to Professor Fried's left is William Weld, a future Republican governor of Massachusetts. At eye level with Professor Fried and to his right is Samuel Berger, who like Messrs. Sanders, Pierce, and Weld will find his way into public service, eventually advising President William Jefferson Clinton from the post of Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs. To Mr. Berger's right and two rows behind sits Mark Joseph Green, late of Cornell University and Great Neck, New York. By the mid-1990s Mr. Green will have nailed down a position as New York City's public advocate and a statewide reputation as a liberal Democrat.

Professor Fried is superciliously droning on in a vaguely British accent about how the visitation of annoying or unpleasant conditions upon a neighborhood (grating noise or belching smoke, for example) can constitute a tort or cause of action for a civil lawsuit.

"Can anyone think of an actionable nuisance we haven't touched on today?" asks Professor Fried.

"What about black people moving into a neighborhood?" suggests Mark Joseph Green, liberal Democrat of Cornell University and Great Neck, New York.

A thoughtful discussion ensues. Henry Sanders looks at me. We five blacks in fact all look at each other. Our faces betray little. In any case, the privileged young white scholars are oblivious. There are legal arguments to be mustered, pro and con. The discussion of whether or not the mere presence of blacks constitutes an inherent nuisance swirls around the five blacks. We say nothing. We cannot dignify insult with reasoned rebuttal. The choice is between ventilated rage and silence. We choose silence.

Mr. Green does not prevail and is foreclosed from extending his argument. Encouraged, he might have made Harvard Law School a plaintiff in a theoretical nuisance suit against the twenty-five blacks admitted to its class of 1970.

Doubtless Mr. Green will not remember his attempt to expand the definition of nuisance as a tort. Thirty years later I will not have forgotten.

1949: Richmond, Virginia

Maxie Jr. and I sit in the living room on a late Sunday afternoon going through Daddy's scrapbook while waiting for Miss Washington to collect us in her black four-door 1948 Plymouth. Maxie Jr. is ten and I am eight. Miss Washington is my brother's spinsterish fifth-grade teacher at Baker Street Elementary School. On Sundays after dinner she sometimes takes the two of us for a ride in her polished sedan.

The couch is old and sags in the middle, causing us to lean together while turning the dog-eared pages. The couch, which sits astride the hearth and blocks the fireplace in the tiny room, is flanked by end tables atop which rest maroon ceramic lamps bearing the oval portraits of two Victorian white women whose faces are framed by tight coils of dark hair that reach from scalp to bodice. My sister Jewell won the monstrosities in a teen essay contest.

The floor is covered by a piece of linoleum with broken edges. The raw wood perimeter floorboards have been painted with dark brown deck paint by Mama.

The scrapbook rests on a coffee table that matches the lamp tables. The set is made of mahogany wood with inlaid leather tops. I am proud of our tables. We are careful not to score the leather surface with the plywood scrapbook covers.

Attached to the black pages by tiny paper corner frames are serrated black-and-white photos from the early 1930s. The yellowing news clippings are pasted directly onto the stiff paper. The slight man in the football uniform does not look like my father. His helmet is nothing more than a leather skullcap. His jersey has no number and is decorated only by leather strip appliques. He wears no shoulder pads and no thigh pads. Hip pads stick up out of his skimpy pants at unstylish angles.

MAXIE ROBINSON SCAMPERS FOR

AN 80 YARD TOUCHDOWN

IN VIRGINIA UNION VICTORY

This is the headline from the article pasted under the picture. Another picture on the page shows Daddy running with a ball that looks as much like a basketball as a football. I look hard for Daddy in the pictures of this lithe young athlete with blazing speed but cannot find him. The Daddy I know just waved to us on his way out. By 1949 he is forty-three years old, overworked, overweight, and suffering from high blood pressure, but he has remained a handsome man of forbidding countenance.

Daddy's mother and father married in Richmond in their adolescence and divorced shortly after he was born. His father left for Baltimore, remarried, and unburdened himself of his only child. His mother also married again, this time to a disengaged alcoholic who worked for the railroad and played the guitar alone in his bedroom.

Maxie Cleveland Robinson Sr., with a mother scarcely fifteen years his senior, largely produced alone the man he was to become--a highly principled teetotaler, unaccustomed to the social domesticities of family life and with small gift for intimacy.

Doris Alma Jones, my mother, grew up in Portsmouth, Virginia, in a large white shingled two-story house on Palmer Street between Effingham and Chestnut. She was the first of seven children born to Nathan and Jeanie Jones. One child, a boy, died in infancy. Six survived to great age, a boy and five girls including my mother, now eighty-three.

Mama and Daddy had met years before in Richmond at Virginia Union University, a small school with a large reputation for producing epic preachers (Sam Proctor, Wyatt Tee Walker, Walter Fauntroy). Mama had come one hundred miles up from Portsmouth to prepare for a teaching career. Daddy, who had grown up in Richmond, was working his way through college by taking courses one year and a job the next. She was eighteen and he was twenty-six when they were introduced. He was as iron-willed and determined as she was naturally brilliant. Starring in every sport, he was the campus hero and a local legend. She was a straight-A student and beautiful. I suspect that Mama was smitten by him early on, for Daddy had an overpowering room-filling presence about him--heady stuff for a eighteen-year-old girl never before away from home.

Mama was twenty in the summer of 1933. Portsmouth was in the grip of a late July heat wave. Mama and her ten-year-old sister, Evelyn, moved back and forth in the bench swing on the front porch of the old family house trying to win a margin of comfort from the motionless hot air. In May, Mama had completed her first year of college and come home for the summer. Since arriving, her thoughts had been increasingly of Daddy. During the school term in Richmond, they had gone together to the movies and sorority dances. He had kissed her the first time on their sixth date. It was an age of reticence, and the term ended before they could properly reveal to each other a fraction of what they were beginning to feel. Daddy was working during the summer as a waiter in Virginia Beach. In the fall, he would leave for Atlantic City to work in a similar capacity until spring. She had no idea when she would see him again, if ever. She had said nothing to her family about this new man looming so large in her reveries. Premature talk might have jinxed hopes that were, at once, exciting and scary. He was not her first beau, even if she could possessively think of him in such terms, which she could not. Yet this feeling was new and very different.

It was noon. Evelyn's feet touched the porch floor but without purchase. Mama absentmindedly tugged at a loose string from the waist seam of her cotton house dress and moved the swing backward.

A half-block away, a battered city bus stopped at the corner, and a man stepped off. He wore a Palm Beach suit of beige linen, white shirt, dark tie, and bone-colored shoes. The bent brim of his panama straw hat shaded his eyes.

"Oh my God," Mama said in disbelief, her heart suddenly racing. Evelyn, alarmed, said, "What is it, Doris? What is it?"

"Evelyn, a gentleman is coming to see me."

Mama was out of the swing and at the door before Daddy could catch sight of her.

"Tell him, tell him, I'll be right down."

Daddy stood on the steps in the shade of the forest green porch awning and waited alone, Evelyn having delivered the message and disappeared into the house. Ten minutes later, Mama came through the screen door onto the porch. She was wearing a light blue, full-skirted voile dress and white summer sandals. She wore no jewelry. Her parents did not approve of lipstick. Save for a trace of blush on her cheeks, she wore no makeup at all. Daddy stepped up onto the porch, took both of Mama's hands in his and kissed her lightly on her forehead.

"You are looking beautiful," he said. Mama blushed. They sat in the swing and chatted.

"I would like to meet your parents," Daddy said.

"Papa's at work but Mama's here."

The discussion with my grandmother, though formal, went well.

"If it would be all right with you, Mrs. Jones, I would like to take your daughter to a movie this afternoon." Mama had never been anywhere on a date in Portsmouth unaccompanied by her eighteen-year-old sister, Hattie.

"Mr. Robinson," my grandmother said while moving with Mama toward the screen door, "if you would excuse us for a moment." In the foyer, she looked at Mama and came directly to the point. "I don't know this man."

"But he's a good man, Mama. He's a gentleman."

"Well, I guess you can go. After all, it is broad daylight."

They walked the mile down Effingham Street to the Capitol Theater, trailed much of the way by an incorrigible neighborhood rascal chanting, "Doris got a boyfriend! Doris got a boyfriend!"

On August 31, 1936, at noon, Mama and Daddy would marry on that same street at the home of Reverend Harvey Johnson before sailing in the evening from Norfolk on the Washington Steamer bound for the nation's capitol. It was on their honeymoon that Daddy presented Mama with her first tube of lipstick. "I don't want your mother to see me wearing lipstick," Mama said. "Don't worry," said Daddy, "she wears a little herself."

Mama had taught school in rural North Carolina for a short time before they married. He had already become a history teacher and ail-sports coach at Armstrong, one of Richmond's two black high schools. She became a housewife, mother, and public speaker. Our household income would never exceed $11,000 per year.

Mama and Daddy were the only heroes I've ever had. Not that other, global figures I've come to know in adulthood aren't worthy. But hero appreciation should be born of a close and varied knowledge and must, when healthy, die with childhood.

[]

We hear the horn of a car. It is Miss Washington's Plymouth, we know. I close the scrapbook with care and return it to the coffee table. Soon Maxie Jr. and I will be heading out for our Sunday ride.

The dark flat is long and narrow. There are four units in the red brick building, two up and two down. All four units have long skinny backyards, but only the two ground-level units have front porches and front yards. We live in one of these. The porch is small with a gray-painted wooden floor. Five of the boards have been replaced by the landlord the month before and left unpainted. The yard, more flower patch than yard, runs beside the porch and to the sidewalk.

Mama is showing Miss Washington her flower garden, which is just beginning its annual show. The creeping red phlox has bloomed for weeks. The tall, elegant irises wait their turn. The thin, upright Miss Washington, who looks like anything but a gardener, seems to be enjoying herself although unable to identify any of Mama's flowers by name.

Mama is bending over and pointing. "This is called sweet william." I like the name more than the plant. Miss Washington smiles but does not bend. "And these are snapdragons." I do not like the plant because of its name.

Maxie Jr. and I sit on the porch glider and wait. On the floor beside us are four empty quart milk bottles. The milkman will retrieve them when he delivers fresh milk tomorrow before Jewell, Maxie Jr., and I begin the walk to school.

Today we are wearing our white Sunday shirts, which will be worn again to school tomorrow before Mama washes, starches, and hangs out the family's wash on Wednesday. We look well turned out in our stiff shirts, suit trousers, and clean shoes.

"Are you ready, young men?" asks Miss Washington.

"Yes ma'am," we answer in unison.

There is the scent of dung in the air. Weekdays, old Mr. Johnson brings a horse-drawn vegetable wagon through the neighborhood and sells his goods from wire and wood produce baskets that hang from the wagon's sides. Evidence of his route is piled on the street not far from Miss Washington's Plymouth.

Riding in a car is a rare treat, and Maxie Jr. and I do not disguise our joy as we pull open the heavy rear doors that swing away from the thick post in the sedan's middle. This is our first ride with Miss Washington since the fall. The route does not matter, and the ride never seems to last long enough. On Leigh Street we cruise past High's ice cream parlor where a two-scoop cone costs five cents and a three-scoop cone unaccountably costs ten cents. Up at the corner is Tony's confectionery where on my walk to school, unknown to Mama and Daddy, I often spend all thirty cents of my lunch money for six boxes of Raisinets. A. D. Price Jr. is standing in front of his funeral home. We think he must be very rich. A big hard-drinking man with a low gravelly voice, he is easily the most charismatic man in our neighborhood. He calls out to us as he prepares to step into his Cadillac convertible.

Farther along Leigh Street on the left is our barber shop. It is named, oddly, Your Barber Shop. A haircut costs fifty cents. Daddy takes us there every other Saturday. He likes it because Pop, the sixty-five-year-old proprietor, allows no profanity or blue talk.

Miss Washington turns left and drives down Broad Street, the city's main artery.

"You young men having a good time?"

"Yes, Miss Washington," we chime.

She drives with her eyes to the front and both hands high on the wheel. Her posture is sclerotic. We turn off Broad into Capitol Square where the governor's mansion is located.

"Boys, this is where the governor lives," she announces in a tour-guide voice.

"Yes ma'am," we say. She does not know that Maxie Jr. and I have been to the mansion several times before, banged on the front door and run. We do not like the governor. But we say nothing to Miss Washington.

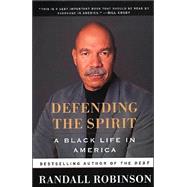

Copyright © 1998 Randall Robinson. All rights reserved.