Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

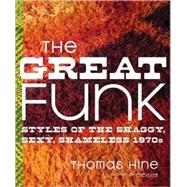

Thomas Hine writes on design, culture, and history. He is the author of five books, including Populuxe. That title, coined by Hine to describe the styles and enthusiasms of post–World War II America, has entered the American idiom and is now included in the American Heritage and Random House dictionaries. From 1973 until 1996, Hine was the architecture and design critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he wrote a weekly column called “Surroundings.” He has worked as an adviser for museums across the country and contributes frequently to magazines, including The Atlantic, Martha Stewart Living, Architectural Record, and others. He lives in Philadelphia.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Excerpted from The Great Funk: Styles of the Shaggy, Sexy, Shameless 1970s by Thomas Hine

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.