Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

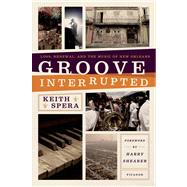

KEITH SPERA writes about music for The Times-Picayune in New Orleans. In 2006, he was a member of the newspaper’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Hurricane Katrina coverage team. He has also contributed to Rolling Stone, Vibe, Blender, LA Weekly, Garden & Gun and numerous documentaries. He lives in his native New Orleans with his wife and two young children.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.