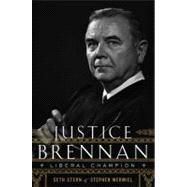

This book is a sweeping and revealing insider look at court history and the life of William Brennan, champion of free speech and public access to information, and widely considered the most influential Supreme Court justice of the twentieth century.

Before his death, Brennan granted coauthor Stephen Wermiel access to a trove of personal and court materials that will not be available to the public until 2017. Wermiel also conducted more than 60 hours of interviews with Brennan over the course of six years. No other biographer has enjoyed this kind of access to a Supreme Court justice or to his papers.

Justice Brennan makes public for the first time the contents of what Jeffrey Toobin calls “a coveted set of documents,” Brennan’s case histories, in which he recorded the strategizing behind all the major battles of the past half century, including Roe v. Wade, affirmative action, the death penalty, obscenity law, and the constitutional right to privacy.

Revelations on a more intimate scale include how Brennan refused to hire female clerks even as he wrote groundbreaking women’s rights decisions; his complex stance as a justice and a Catholic; and new details on Brennan’s unprecedented working relationship with Chief Justice Earl Warren. This riveting information—intensely valuable to readers of all political persuasions—will cement Brennan’s reputation as epic playmaker of the Court’s most liberal era.

"This sweeping biography of one of the most influential justices ever to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States invites the reader to witness the details of William J. Brennan Jr.'s personal life, the darker moments, as well as those that shine. It seats the reader in Brennan's chambers to listen to his conversations and see the memoranda exchanged with other justices and his law clerks ... In sum, the biography is an intimate account of Brennan's life, especially his 34 years on the Court."--Newark Star Ledger

"The book offers an intelligent and interesting account both of Brennan's decades on the Court and of the broader developments in American life that intertwined with the Court's work."--Ed Whelan, National Review Online

"The book takes care to place decisions and opinions in the context of Brennan's personal history, judicial philosophy and larger societal factors. It's deliciously gossipy when discussing how certain justices voted and what their opinions were of each other, but that information's also vital when understanding how the court operated."--Dan Herman, Pacific Northwest Inlander