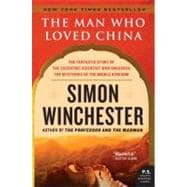

In sumptuous and illuminating detail, Simon Winchester, bestselling author of The Professor and the Madman, brings to life the extraordinary story of Joseph Needham-the brilliant Cambridge scientist, freethinking intellectual, and practicing nudist who unlocked the most closely held secrets of China, once the world's most technologically advanced country.