Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Acknowledgments | ix | ||||

| Preface | xi | ||||

|

|||||

| Foreword | xiii | ||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Introduction | xvii | ||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

1 | (14) | |||

|

|||||

|

15 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

25 | (14) | |||

|

|||||

|

39 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

49 | (14) | |||

|

|||||

|

63 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

73 | (6) | |||

|

|||||

|

79 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

87 | (6) | |||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

93 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

103 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

113 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

123 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

131 | (12) | |||

|

|||||

|

143 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

151 | (12) | |||

|

|||||

|

163 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

171 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

179 | (6) | |||

|

|||||

|

185 | (10) | |||

|

|||||

|

195 | (12) | |||

|

|||||

| Contributors | 207 | (4) | |||

| About the Editors | 211 | (2) | |||

| Resources | 213 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

NOTHING TO ME

Sophia Gould

At eighteen, I stand on the steps at the art house cinema where my boyfriend works, watching the doors of Theater One. Usually, the moment the lobby clears, we'll find some corner, lean up against the wall, and kiss until a stray patron clears her throat at the counter. Then I'll blush, and my boyfriend will go serve popcorn. Once the patron is gone, we'll tangle up again until the credits run. Because of our displays, the manager has posted a sign that says, "No Making Out--or whatever you kids call it these days."

Today, as usual my boyfriend wears black leather, and tight jeans, and I complement him in torn tights, a miniskirt, high laceup boots. The Gay and Lesbian film festival is showing downstairs, and upstairs it's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer . I can hear the dialogue through the doors of both theaters, and I know we're clear for a good half hour, but I stay on the stairs.

"Come on down," my boyfriend calls sulkily from the ticket booth. I point to the sign, but the truth is I want to stay where I am. I enjoy watching the dykes filter in and out of the theater to order Jujubees and real Cokes. It feels like home. The audience members for the festival are mostly in their late thirties, sporting layered haircuts, beaded earrings, and Frye boots. If I squint, I could mistake them for my mother, as she looked eight years ago. Back then, she kept her hair above her ears and wore overalls or flannel, even home to our WASPy Christmas dinners, even among the pearls and angora of holidays.

My mother is married to a man now and has let her lesbian friends drift away. That era of our lives is not something either of us talks about much. I haven't, for example, found occasion to mention it to my new boyfriend. Once upon a time, talking could have meant custody battles or social workers. Now, silence is an old habit.

Still, there's a comfort in looking at the women here for the matinee. For the same reason, T smile at the tattooed clerk who sells me my cigarettes and the purple-T-shirted band who clump together at pro-choice rallies. They remind me not just of the mother who raised me--now transformed into a microwave owner, a wife, a wearer of costume jewelry--but also of the dozens of women who were my surrogate mothers. Some were my mother's lovers, some just friends who, having lost their children to the courts or never having had any in the pre-turkey-baster decade, were drawn to me as a possible or temporary daughter.

The movie lets out, and I watch curiously but absently, half

thinking of the kiss I'll get as soon as the lobby has cleared.

And then, there--nearly unchanged in the eight years since I last saw her--is Laura. Dirty blond, radiating competence, just as I adored her.

Panic. I flush. My chest constricts. I turn, then gallop up the stairs. Leaning over the railing, T watch, then pull away, then watch again until Laura--it is Laura--disappears out the door.

My mother had known her in high school. They met again, both out lesbians, in the early eighties, and fell in love. It was long distance at first; Laura lived in Portland, Maine, and we were in Boston's Mission Hill. On our first visit to her apartment, I made a point of scattering the plastic army figures she gave me around every room. My mom thought it was cute.

"She's marking her territory," my mother said when I got up to join the grown-ups at the table, leaving a half-battled war in my wake.

"Pick those up," Laura said.

Something in her tone of voice made me do it. New lovers, in my previous experience, would indulge me, following my mother's lead. I could go to bed when the grown-ups did, watch late movies, and skip school to make up sleep. My mother believed ice cream could be dinner on occasion. But, as I began to learn, Laura believed in health food and rules. She was an activities director during the summer, and I could imagine she'd be happy with a whistle around her neck.

Rules were not always what I expected them to be. That summer, we went to pick Laura up at the ritzy camp where she headed the outdoors program. All the campers had left, and we scoured the cabins together, collecting the blue uniform sweaters the girls had abandoned, tubes of toothpaste, bars of soap, and other treasures that would see us through the lean winter.

"Taking what rich people leave behind isn't stealing," Laura explained to me. "They don't even think of this as wasting."

My mother and I shopped with coupon books in our hands, picking the green-banded no-name cereals over Kellogg's so that my father's meager support checks and the welfare would last the month. If the lines were long at the checkout, my mother was likely to dash back into the aisles and trade our butter for a jar of artichoke hearts or a bar of Swiss chocolate. On shopping night, we'd feast on the delicacy and then eat our toast dry for the next two weeks. When Laura moved into our home in September, the indulgences ended, but so did the sense of deprivation. She, too, had lived off slim earnings, but she had learned to stretch the checks into sufficiency. Unlike my mother, she was never tempted to sacrifice the end of the week for a Friday-night mimicry of wealth. If we needed more than we could afford, she'd find it for cheap, or free. Laura was the one who insisted we join the food co-op, and she did the volunteer work that kept our membership good. She planted vegetables in our yard, and the nearby Victory garden, and by the start of the school year, I was well trained in lifting rolls of toilet paper from public restrooms.

We were poor, and we stole little things--soaps, paper towels, pens, and sugar packets. My mother thrilled at these activities, filling her pockets with plastic stirrers she insisted we could make into a set of Pick Up sticks. Laura only shook her head slightly at this, but I could sense her disapproval. Later, leaving a small grocery, my mother pulled aside her coat to show us a pair of Chinese slippers that she had lifted, and Laura erupted. We should steal only from big stores or chain restaurants, she commanded, and only what we needed. My mother refused to take the slippers back and refused to pay for them, but after that, she left the stealing to Laura.

I didn't ask questions about these new rules, though they contrasted with the codes of my teachers, their After School Special morality. I already knew it was necessary, even right, to lie sometimes. When my teachers asked probing questions about my mother's roommates, for example, I was trained to feign ignorance. And my world was already one that acknowledged inequities. With my father, I saw first-run movies on weekend nights, and with my mother, I had to eat the stringy carvings of the jack-o'-lantern in a stew. When the kids at school called each other fags, I kept quiet, knowing that I could not argue, as long as my mother might be caught kissing a woman on a street corner, as long as she picked me up wearing jeans and a man's undershirt.

Though our thievery might, in complex terms, have meant something for the salary of the checkout clerks at Bradlees or the cost of necessities for other welfare families, Laura more than paid our debt by her involvement in the community. She and my mother joined the fight against a diesel power plant that a university wanted to locate in our neighborhood; perhaps they thought no one there would have the time or energy to object. And Laura was drawn to the kids in the neighborhood. She'd send stray kindergartners home at dark, help out with a dime for an Icee, bring out the wrench to loosen the fire hydrant on hot days. In Boston, 1980, there wasn't a single racially integrated Girl Scout troop until Laura became the troop leader of a multicolored band of Brownies from Roxbury and Mission Hill. On Wednesday afternoons, Laura would gather the kids of the poor lefties, the Hill, and the projects to cruise vacant lots for edible plants, which we'd roast over campfires between blown tires and rusted tin cans. And she never played favorites with me, even though I was the one who walked home with her. The other troop leader, Susi, was a nice married lady from down the block. I didn't know what she knew about Laura and my mother.

It took me a while to get used to Laura. She was tough, where my mother was indulgent. I had chores, suddenly. They would argue over whether I ought to clean my room.

"It's her space," my mother insisted. "She's the only one who has to live there."

But they were the ones who had to pick through my dirties to do laundry, and besides, Laura said, I'd have to take care of myself some day. I'd try, for a few days, to keep things neat, but when my room began to devolve to its old disorder, I'd wait until Laura was out of the living room before I opened the door on the mountains of toys and discarded clothes. I remember the shame I felt when she stepped over the mess to tuck me in and the way I'd make excuses for the crumpled papers and spilled juice: a social studies report, too tired, I promise I'll clean it in the morning. She looked, shook her head slightly, and reminded me I wasn't the only one who lived in the house. Naturally, I went to my mother when I wanted something. If I came home with a scrape from the playground, I knew which of them to find to show the wound to. Laura might know the proper first aid, but my mother would let me hold the iodine-soaked cotton to my own skin, would hold my hand and hush me as I cleaned the cut.

The second summer they were together, Laura got a job at a camp closer to home and brought me with her. It was a Campfire Girls facility, and most of the kids were from the North Shore, working-class, Catholic. They must have assumed Laura was my mother, and I suppose I let them. The rules were different at the camp. For example, Laura told me, I ought to be careful about my language. And I was, substituting "sugar" for "shit," the way I'd heard my grandmother do. And, I thought wisely, replacing "fuckin'" with "friggin'." The latter, however, turned out to also be considered a "swear" in North Shore circles. "Ooooh," one of the girls tattled, "Sophia said a swe-ar." I was sent to the office of the camp director--Laura--for punishment.

"Well," she told me, winking. "I guess you'll have to be stuck in the office with me." She gave me one of the Popsicles that winning teams got in the color wars, and she made sure my mouth was clean of its orange mustache before I returned to my group.

I first began to think of Laura as one of my parents toward the end of that summer. Camp ended a few weeks before the start of school. Temporarily rich from her summer earnings, Laura took my mother and me on a canoe trip in Maine. While we were drifting during a lunch break, I took a bite of one of the green peppers we'd bought in the supermarket, and instantly my mouth was on fire. I was leaning over the boat, trying to swallow the river, by the time they realized what had happened.

"Jalapeño," my mother said, laughing at my red faced sputter.

It was Laura who handed me the chunk of oily sun-baked cheddar cheese, knowing the grease was the only thing that could neutralize the chile heat. And Laura waited until I laughed before she, too, cracked the smile that must have been pulling at her lips when I was choking down the river water. Laura's severity did not mean unkindness; for the most part, it meant the opposite, a form of affection. Unfamiliar--perhaps uncomfortable--but sincere.

Laura figured out how we could have enough money and things to survive, even if she did it unconventionally. She could fix whatever broke, and she contrived recreations for me that had somehow or other felt out of our financial reach before. But most of all, I think, she brought order to our scattered lives, an order I would need in the year to come. I made a habit of cleaning--or at least tidying--my room before I went to my father's on the weekends. I'd leave the laundry, in two separate piles, outside my door, and it was always clean by the time I returned. If Laura didn't come in with my mother to say good night, I'd call for her. They were my parents, both of them, at least on the weekdays.

The whole fall, I made my mother serve meal after meal of Uncle Ben's Long Grain & Wild Rice. If I saved a certain number of box tops, I could get a Coleman canoe for three hundred dollars, an amount I had nearly saved from birthdays and Christmases in my bank account. It was a brand-name prepackaged food that must have meant sacrifices for my mother, too, but she never let on. That Christmas, I gave Laura a beautiful green canoe. She took me into her lap and thanked me, then began to explain that we couldn't afford it, that she'd have to return it. I could feel my eyes burning. My mother tapped her on the shoulder, and they slipped off into the other room. I heard whispering and looked at the unopened packages with my name on them, trying to be excited. When they returned, Laura was smiling.

"Thank you, Sophia. It's a wonderful gift. We'll canoe in it till we're all old ladies."

When Laura went to make the coffee, my mother told me in a soft voice that she'd explained to Laura how the canoe would pay for itself, making up the cost of rentals in just a few years. Then she laughed.

"No, really, sweetie. She's keeping it because you gave it to her. Because she loves you."

In my memory, that was the day we were closest, most a family. My mother brought out her gift, three different-sized oars, which I had not been able to afford, and we climbed, one at a time, into the canoe, and mimed paddling down the river, while the other two steadied the boat on the scratched wooden floor.

Perhaps my mother sensed already, that Christmas, that whatever they whispered in the kitchen was the map of the end to come. But I was a child, and I could not read in these signs a possibility of an end. In a way there is no word for, I had also fallen in love with Laura. I had chosen her as my parent, chosen to take her rules as my own. But I had never chosen the risk of losing her. I assumed that, loving her as I did, she would stay forever. We would really canoe, gray haired, in the new boat, long after it had cracked and been repaired. Maybe I understood that my mother and Laura might split up. After all, my mother had left lovers, her husband, before. But Laura had become my parent and parents do not leave their children--after my father and mother divorced, he was still in my life, on weekends and holidays. I was ten years old; I never imagined that someone I loved might leave me, too.

DESPITE THE EFFORTS OF my mother's and Laura's group, construction began on the diesel power plant. From the top of Mission Hill, we could see the outline of smokestacks, growing higher almost daily. Watching it one night, Laura and my mother began a quiet debate of words I didn't understand, quick spelling out of letters I would lose track of before they formed sentences. When I asked what they were talking about, they both hushed, but after I went to bed, I heard their angry muffled voices from behind their bedroom door.

One night, when I was at my father's house, my mother and Laura went to spray-paint the community organization's symbol--a white elephant--on the walls of the university club. A witness phoned the police, who arrived midway through the painting and packed everybody roughly into the paddy wagon. My mother was the only one who spent the night in jail, the suspected driver of the getaway car, our Chevy van. The witness claimed she had watched my mother for a full three minutes and could make an identification--which, in legal terms, meant my mother could face eight years in jail.

They told me none of this. I watched the two of them bicker as they scrubbed every crevice of the car clean. No one asked me to help. When the doorbell rang, Laura would jump to get in my way, then eye our caller through the peephole before she'd slide the door open a crack. My mother told me I was no longer to answer; there had been a crime in the neighborhood (but there had always been crimes). I knew something was wrong, but I could tell by their silences and awkwardness, by the growing tension between them, that I shouldn't ask.

A month or so later, a group of women of my mother's height and coloring gathered in our apartment in the early morning to struggle into straight clothes, suits and lipstick, and accompany my mother to the police station for the lineup. The primary witness pulled the one woman in jeans from the group, a woman not my mother. Photos of the event showed officers without badges, twisting demonstrators' arms. The organization threatened a countersuit, and my mother got off.

But the events had taken their toll. My mother and Laura's arguments would already be in progress when I got home from school. A silence might fall for half an hour or more, while Laura walked around the block, but she'd return, pick up a grocery receipt, and circle each purchase she considered unnecessary. One afternoon, my mother met me at the door and took me to a shopping center, where we tried on ridiculously expensive headbands, patterned in red, purple, and green. I put each one back.

"Choose anything you want. My treat," my mother said. "We don't always have to suffer." But she couldn't find one she wanted, either. When we got home, Laura was still out, and it was nearly midnight when she finally put her key to the door. I heard them talking sweetly to each other in the bedroom, and I hoped it would be all right, but the next day, they were fighting again.

As I remember it, Laura's voice stayed calm and low, as my mother's pitched into screams, but this may not be fair. It may not be true that Laura was always right in these arguments but I felt, miserably, disloyally, that I was on her side. It may have only been that I wanted her to stay. And I began to realize, she did not have to. That was the difference. My mother did, and I could afford to sacrifice my support of her. Just be quiet , I whispered, hoping somehow my mother would hear it through the closed door.

When they argued, I went into my messy room and shoved toys and dirty clothes in the closet, the dollhouse furniture under the bed. I picked up the last miserable sock, the last Monopoly piece, the last thing that might make Laura give up on me for good.

* * *

LAURA LEFT WITHOUT A word. She took the canoe and, absurdly, ran off with Susi, her Brownie troop co-leader. My mother took me to an ice-cream shop and tried to explain over our banana splits. "I guess she just didn't care enough about us to say good-bye," she told me.

A month or so later, living in a new apartment where the memories were not so vivid for us, my mother found a note on the windshield of the van. She read it and ripped it up. When I asked her what it said, she told me it was from Laura. She wanted the rest of her stuff back.

A few weeks pass, and I tell my father the story of seeing Laura at the movie theater.

"Why didn't you talk to her?" he asks.

"She Left us," I say, and it's in my ten-year-old voice, long-lost self.

"You know," he says, "She tried to see you. She called me a few times, I guess it must have been after their breakup, and said she wanted me to arrange a meeting between the two of you. She said your mother wouldn't let her see you."

"And you didn't tell me?"

"Sophia," he says, "I had no idea what the story was. I couldn't get involved."

It is impossible for me not to wonder what the note on the windshield said or whether Laura had taken the canoe not because it was a nice boat but because I'd gotten it for her.

Years after that night in the movie theater, I became involved with a woman and on one of our first nights together, told her the story of my mother's relationship with Laura and my loss. Though my romance with this woman was short-lived, it opened the story for me again, and I began to search for Laura. I looked in the phone book for her very common name and penned a short, safe letter:

Dear L. Brown: I have taken your name from the phone book because I am in search of a person of the same name. If the following description doesn't match yours, please disregard this letter. My name is Sophia Gould. I am looking for a woman named Laura Brown. She was my Girl Scout troop leader in Mission Hill and a good friend of my mother, Susan Patrick. Laura meant a great deal to me. I am nineteen now, a student at Columbia University. If you recognize these details, please write me back at the above address.

(Continues...)

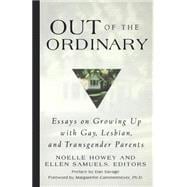

Excerpted from OUT OF THE ORDINARY by . Copyright © 2000 by Noelle Howey and Ellen Samuels. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.