MICHAEL COUMATOS is a former U.S. Navy test pilot, ship's captain, and commodore; U.S. Space Command director of wargaming; and a National Security Council counterterrorism advisor.

WILLIAM B. SCOTT is a retired bureau chief of Aviation Week & Space Technology and a nine-year Air force veteran who served as aircrew on nuclear sampling missions. He is a six-time Royal Aeronautical Society "Journalist of the Year" finalist, and won the Society's 1998 Lockheed Martin Award for the "Best Defense Submission." He also received both the 2006 and 2007 Messier-Dowty awards for "Best Airshow Submission."

WILLIAM J. BIRNES is the New York Times bestselling coauthor of The Day After Roswell and Worker in the Light.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

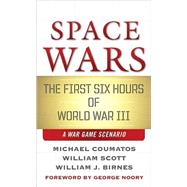

Excerpted from Space Wars: The First Six Hours of World War III by Michael Coumatos, William Scott, William J. Bimes

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.