Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

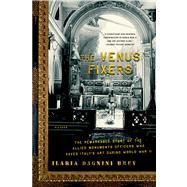

Ilaria Dagnini Brey is a journalist and translator who was born in Padua, Italy. She now lives in New York City with her husband, Carter Brey, the principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic. This is her first book.

| Maps | p. x |

| Prologue | p. 3 |

| Italian Art Goes to War | p. 9 |

| "Men Must Manoeuvre" | p. 39 |

| Sicilian Prelude | p. 60 |

| The Birth of the Venus Fixers | p. 74 |

| The Conflict of the Present and the Past | p. 92 |

| Treasure Hunt | p. 110 |

| Florence Divided | p. 147 |

| A Time to Rend, a Time to Sew | p. 177 |

| The Duelists | p. 200 |

| Alpine Loot | p. 229 |

| Epilogue: A Necessary Dream | p. 254 |

| Notes | p. 263 |

| Select Bibliography | p. 283 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 289 |

| Index | p. 295 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

PROLOGUE

Florence looked pale and indistinct to Lt. Benjamin McCartney as he approached it aboard his Martin B-26 Marauder on the morning of March 11, 1944. It wasn’t haze that blurred the city skyline on that morning; in fact, as he would later write, “the weather was perfect, the visibility unlimited.” A sense of impending tragedy seemed to drain the beautiful city of its color in McCartney’s eyes as it slowly came into view. He had told his crew - his pilot and friend, Capt. Leonard Ackermann, his co-pilot, Lt. Robert Cooke, and their three enlisted men - that they would soon see Santa Maria del Fiore, Our Lady of the Flower, a cathedral so massive and ambitious that it took the Florentines 175 years to erect it; once built, in Giorgio Vasari’s words, “it dared comparison to the heavens.” A few yards away stood the baptistery, Dante’s “beautiful Saint John.”

“Tell me it’s a real pretty city,” the radio gunner Callahan said from the windowless interior of the bomber. It was. In fact, to Lieutenant McCartney, a twenty-eight-year-old Harvard graduate and a well-traveled man who had visited Florence five years before, the city had seemed lovelier and richer in art than any other in the world. Elusive also: “seeming to belong to time, not to us,” he recalled. Since that trip, a few months before the onset of the war, he had often thought with concern of the city’s most fragile treasures, but found comfort in the notion that Florence’s monuments would be its protection and that the tide of war would never reach such a beautiful place. On that March morning, though, it was his job to bomb it.

“It’s a compliment,” the group bombardier told McCartney and his crew on leaving the briefing room that day. The target of the mission was the Campo di Marte marshaling yards, a narrow area dangerously close to the intricate web of old streets and alleys and the heart of Florence. The mission’s success depended on the technique of precision bombing that had been greatly improved over the course of the war. In North Africa and later in Italy, Lieutenant McCartney and captain Ackermann had been assigned to more and more difficult raids over the harbors, bridges, and large supply depots, with smaller and smaller objectives. At that stage in the war, the American lieutenant could confidently declare that only a few groups of bombers in the world were capable of performing this difficult task.

“Sure got a lot of things we can’t hit,” a bombardier had said during the briefing as he looked at a map of Florence, where white squares marked historic buildings that were to be avoided. Indeed, there probably were more white squares than plain background on that map. But how could Lieutenant McCartney explain, in the few minutes preceding the mission, what it was that made those white markings so untouchable, and what surrounded them almost as precious: the lovely churches and elegant squares, the austere Renaissance palaces that his dazzling treasure, the small medieval houses overhanging the slow-flowing Arno, the graceful arch of the Ponte Santa Trinita and the tiny goldsmith shops lining the Ponte Vecchio? As he boarded his bomber, McCartney’s minds, he wrote later, was burdened by “one of the greatest responsibilities of the war, a responsibility felt, but not actually shared, by civilized people all over the world.”

“How come we are bombing it? Just asking,” Callahan said.

After circling above the city, the four planes came over their target and tightened their formation. The bomb bays slowly opened. At about four hundred feet wide and two thousand feet long, the Campo di Marte was a narrow strip to hit. Lieutenant McCartney patiently waited for the freight cars and the rail tracks to come under his crosshairs. He watched his bombs fall “in languid, reluctant strings.” The mission was successful. As the plane climbed to higher altitudes, the heart of Florence still huddled untouched, if alarmed, around its watchful dome, where the railway tracks were reduced to a tangle of bent steel. These, to answer Callahan’s question, had connected the Italian war front, which for months had been tapped around the town of Cassino, several hundred miles to the south, to Germany through German-occupied Florence. Reluctantly, the Allied Supreme Command had come to realize the necessity of bombing Florence, despite its artistic significance and the negative propaganda that such action would very likely provoke. As Lieutenant McCartney sorrowfully understood, despite its “loveliness and outward innocence,” Florence in March 1944 was “an instrument of war.”

On that same date, the northern city of Padua was also the target of an Allied bombardment. As the seat of some of the reconstituted Fascist government’s ministries, the small medieval town with its old university was a far more obvious and less controversial strategic objective. Just as in Florence, the mission’s goal was the destruction of the city’s marshaling yards. No precision bombing was deemed necessary, though, even if close to the site stood the celebrated fourteenth-century Scrovegni Chapel, its simple exterior of red brick hiding one of the highest achievements of medieval painting, Giotto’s frescoed stories from the New Testament and from the life of the Virgin Mary. The strike resulted in one of the worst artistic disasters of the Allies’ Italian campaign. A couple hundred yards separated the chapel with Giotto’s luminous frescoes from the Gothic Church of the Eremitani; tucked between the two, an old convent housed the Fascist military headquarters. Although the headquarters was not among the bombers’ objectives that day, for months the parish priest of the Eremitani had pleaded with the Fascist authorities to vacate their seat on account of the grave danger it posed to the two monuments. On March 11, 111 B-17 Flying Fortresses unloaded three hundred tons of explosives. The bombs shook the Scrovegni walls, but Giotto’s fragile work was undamaged. However, four bombs fell on the Eremitani, destroying its façade and a large part of its roof. To the right of the church’s apse, the Ovetari Chapel, a rare example of early Renaissance fresco painting in northern Italy that had revealed the talent of Andrea Mantegna when first unveiled, was pulverized.

At the other end of the peninsula, in the Apulian town of Lecce, 2nd Lt. Frederick Hartt, a photo interpreter with the Allied forces in the Mediterranean, saw the aerial images of the raid on Padua only hours after the disaster. As he pored of the photos, he quickly located the site of the church and realized the enormous nature of the loss. An art historian in civilian life, the thirty-year-old Hartt could not sleep that night, but paced the streets of Lecce and cried. The story of the Ovetari’s decoration, steeped in intrigue and murder, was deeply familiar to him. Mantegna, the son of a carpenter from a village near Padua, was only eighteen and the youngest of six artists when he started painting the chapel in 1448. Work had spanned a decade, and during those years the oldest among them, Giovanni d’Alemagna, had died suddenly, Antonio Vivarini had withdrawn from the project, and Nicolò Pizolo, a talented artist who was, however, “more keen on the use of arms than dedicated to the practice of painting,” as Vasari remarked in hisLives of the Painters, was killed in a tavern brawl. The chapel’s commissioner, Imperatrice Ovetari, proved as formidable a patron as befit her name, “Empress.” She did not trust, at first, the young artist’s competence, and called his old master, the Paduan painter and tailer Francesco Squarcione, to judge his work. Envious of his disciple’s brilliance, Squarcione deemed Andrea’s figures as hard as stone and “lacking the suppleness of flesh.” At a later stage, the relentless Donna Imperatrice sued Mantegna for painting only eight of the twelve apostles she expected to see in the scene of the Virgin’s Assumption. Still, at twenty-three, Mantegna was alone with virtually an entire chapel to fill with painted stories. Perched on the scaffolds, working away on the high halls and vaulted ceiling of the chapel, he brought the innovative language of the Tuscan Renaissance to the provincial town of Padua. While the paint was still fresh on the wall, Marquis Ludovico Gonzaga admired the young artist’s work so much that he invited him to Mantua, where Andrea would serve as his beloved court painter until his death.

Mantegna’s exalted world of martyred saints and Roman warriors in glinting armor was now reduced to a pile of incinerated shards the size of stamps. A cloud of thick smoke hovered where the chapel had stood. Hartt told a friend years later that a gusting wind was probably responsible for the disaster. It had blown a cluster of bombs over the church. The image of the destroyed chapel, looking like a cardboard box crushed by a thuggish fist, haunted him, overlaying the memories of he time he had spent studying those frescoes, amid shuffling feet and the murmur of voices reciting a rosary, while the faint scent of candle wax lingered over the pews. Years before in Mantua, he had stood for hours, rapt, craning his neck up at the enormous frescoes of Giulio Romano, the Mannerist artist who was the subject of his doctorate. “Mr. Hartt,” the custodian of Palazzo Te would say, “here are the keys. Will you put them back in my ward when you’re finished, and switch the lights off, please?” For months, after joining the army in 1941, Hartt had wanted to be part of the team of men whose job it was, for the duration of the war, to fight to protect art. The destruction of the Ovetari Chapel sharpened his determination. On April 6, 1944, he wrote to Ernest De Wald, director of the Allied Subcommission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, to beg for reassignment as a monuments officer:

Dear Maj. De Wald,

…[T]he Eremitani has been very badly hit, & the Ovetari Chapel, with all the Mantegnas, utterly wiped out. As a matter of fact, you can hardly tell there was a building there. The last of the stick of bombs missed the Arena chapel by a mere hundred yards…With Florence, Rome & Venice great care is being taken, but not with the other centers, and if you do not wish to see the great work of architecture & fresco painting ground off one by one, prompt action will be necessary…Right now I should characterize the situation as desperate.

Maj. Perkins and Maj. Newton turned up here about 10 minutes after I located the Eremitani destruction, and before the initial shock had worn off. They were able to verify the tragedy in stereo.

I hope you will be able to fish me out of A-1.

With all best wishes

As ever,

Fred