What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

He was the boy with a dog. Standing in the first row, singing, she'd turn sometimes when she heard his voice: first tenor, clear and bright. For days he'd wear the same baggy sweater -- burgundy; worn at the elbows, covered always with lint. Once, before her family moved to Paradise Valley; her father had promised she could have a dog.

He wasn't from here either. In 1978, nobody was. He was new -- a transfer, midsemester, from Illinois. He was quiet, and shy, and strangely confident of his own voice, as if just waiting to be discovered. Standing there, with him behind her in the choir, his sweater all full of fur, she would listen to him pierce a high C. She knew a lot about scales, would spend ten minutes a day, the start of each practice, warming up on her flute. In the afternoons, after arriving home, having departed the bus, having walked the three long blocks in the sunshine home, there she would wait for her father to call from his office and ask if she'd practiced yet. In Paradise Valley, the streets were newly paved, and there were no sidewalks, or telephone poles. Her father, excited about the possibilities of fiber optics, explained that here communication traveled underground. He explained that here everything was new. The valley, he explained, was fed by a series of rivers, the Salt and the Verde, the Gila, tributaries of the Colorado now linked by a growing system of canals and locks which had brought their family, as well as everybody else, here to live. At home, meanwhile, she spent a lot of time practicing, even if she knew it would be hopeless. She was good enough to know why she would never be really good -- exceptional, her father would say, hopefully. She was smart enough to know the world didn't need another girl who could play the flute.

Once a guy learned she could play the flute, she knew precisely what he thought about. When she played, she'd lift the piece to her mouth, set her lip, her wrist now in full display. She kept her sleeves uncuffed, each rolled twice, but never more. The scars from a childhood accident began at her fingertips and ran past her elbow, toward her shoulder. When people asked what had happened, usually girls, because guys were too ashamed to admit they had noticed...whenever a girl asked what had happened, she always wanted to know just how.

A pot of boiling water? You were eleven?

Elizabeth doesn't remember any of it clearly. She doesn't recall the trip to the hospital, the sirens lit up like a parade, bright as day. Her mother once confessed the police had called to check up on her. They worried, her mother explained, it might have been done on purpose -- the water, scalding, and the flesh it had destroyed there on her arm. Now her mother says that true pain is always merciful. It hurts only by way of memory, long after the fact, and by then it has become bittersweet: like a kiss, provided by a shy boy you will not grow up to marry; or a slap delivered sharply by somebody you have been instructed by your life to love. Somehow, her mother says, tenderly, you have been made...not necessarily better, but stronger...for it.

Do you see?

It's not the pain which matters, she has come to realize, but the way you carry the memory of it with you afterward. Each day she would rise, and dress, and then roll up the cuffs of her sleeves. When she was tan it was easier not to notice. In Paradise Valley, you could spend a lot of time working on your tan. In the pool, swimming,like a fish,her father says...in the pool, swimming, you could let the water lead you to reflection. The sun also provided a fine excuse to put lotion on your body. On one arm, the skin was gnarled, twisted with burnt tendons and ligaments, its design complicated further by repeated skin grafts lifted from her hip and thigh. But on the other...the other...and her shoulders, her belly, and those places surrounding those territories plundered for grafts...there the skin was smooth as water. Eager as light. There she felt it possible to slip away inside herself, often, as if she were a dream.

Nights she found herself dreaming about the boy with the dog. He was short, almost scrawny, with black curly hair, and he could hit a high C. His name was Irish, like a song, the way you could cause the name to lilt, lingering a while in the back of your mind, or throat. Sometimes a boyfriend would call her up, usually after eleven, while she lay in bed dreaming about the boy with a dog.

"Hello?"

"It's me."

"Hi."

"What are you thinking about?"

And then one night she realized it was best never to ask a question unless you really wanted to hear the answer.

McConnell...that was his name.Patrick McConnell.The boy with a dog. The boy who could hit a high C and make your flesh goosepimple -- the skin, rising of its own accord, as if to meet with someone warm. The boy who sat by himself during fourth period while she walked by every day with Bittner, or others, and who always pretended not to notice, never looking up even to catch her eye. Still, she noticed things. She noticed he wrote with his left hand, that he read from a different paperback each week, often tucking one into the back pocket of his jeans; she noticed his eyes, blue, and the nails bitten to the quick, and the old leather shoes with bright red laces. He had skin like a baby, too -- opalescent, and sweet. Once she even stood behind him in a line. Then she pressed her body into him, like a kiss, and held it there.

"Oh," he said, turning.

"I'm sorry," she said, pleased with the excuse.

He smelled like fresh laundry and wet wool and bread. His sweater was dark as blood, nearly threadbare, and then he receded, farther into the line, into the throng, until he disappeared entirely from view.

That night she had a dream he came to her.

Copyright © 1998 by T. M. McNally

Chapter 2

My dog, his name was Germs. He was an English setter with orange points, which is a big kind of dog. The kind that stands right up to your hip. I'd never had a girlfriend.

Of course I'd thought about it, often, and then for a while I thought I wasn't exactly the type that was supposed to have one. I thought, Well, you get what you deserve. You get what you never wish for. My father used to say strength was the gift of humility. He'd say only the humble can be truly strong. Then when I asked him once how I might become humble, he told me not to worry. The world will take care of that, he said.Soon enough.I remember because we were in the garage, and he was smoking a cigarette, the smoke curling up alongside his arm, and it was winter then, and cold. I remember he was building a set of jumps, regulation size for my dog -- a project to clear his head -- and he asked me to pass him the hammer. Then he taught me how to use a plumb line.

A year later, after he had died, and after we had moved to Arizona, in February, I was standing in line in my new school, waiting to purchase lunch. I was standing alone at school, just standing there, because of course I didn't know anybody yet, and I was paying attention to the floor so nobody was going to bother and notice me. Being new at school generally means you're going to get picked on, as opposed toup,and I was standing there, looking at the cement floor when these legs came walking by, just these legs in these nice faded jeans walking by, and of course I lifted my eyes, lifting them slowly, you know, to have a look at some girl...and then, well, it turns out to be a girl dating a guy who lifts a lot of weights. What struck me about the girl were her eyes, green; which locked onto mine, as if they had been just waiting to, and then the sheer fact of her hair: long, wavy -- dark as walnut -- reaching past her waist, dressed with a bit of purple ribbon skimming the surface of her hair.

"What you looking at, asshole?" said her boyfriend, stepping forward.

"Nothing," I said.

He put his arm around the girl, who blushed sharply, and said, "You looking at my girlfriend?"

"Nope," I said, because by now I was looking at him, preparing to be pummeled.

"You looking at me then? You a faggot or something?"

It made me nervous, then angry. It's not that I had anything against gay people -- in Illinois, where I had gone to school, I knew a guy who always starred in the school plays, and then there was my voice teacher, in the city, and he lived with a man who had a red beard. For special recitals, at my teacher's home, the man with the beard was always nice to me and congratulated me often. Also the assistant curate at my church, who had overseen my confirmation, was conspicuously single and took up liberal causes. And I remember feeling especially befriended by these men. At the same time, I was also pretty certain I wasn't going to be gay, which is to say I knew even then I was destined to prefer the company of women, even if I did sing in the church choir, and two of the choirs at my high school in Illinois, before I transferred, and even if I'd never been able to hit a decent line drive, or play hockey, or golf. In a choir, a really good choir, it is possible to hear truly a woman's voice; listening, I believe, can be just as fine as looking. On the cusp of sixteen, I spent a lot of my life looking at girls and dreaming about them wanting to be with me, which of course when you are in high school, and recently transferred, you spend a lot of time standing by yourself doing. But I also knew this guy who lifted weights wanted to pick a fight. So instead I shrugged my shoulders. I stepped out of line, thinking I'd go off to the library, maybe to the art books, where I'd be safe.

"Sorry," I said, stepping out of line, making my way.

I could hear people laughing behind me, calling me names, and suddenly I missed my father, who had been a strong man and would have told me what to do. At the funeral, for which the casket was decidedly closed, I had been advised by various counselors that my father was in fact dead. Apparently it was an important thing to make clear -- especially in cases of suicide. They meant well, I knew; they also felt sorry for me, which made me feel sad and tolerated. Meanwhile at church I had taught myself to pray for my father, because he was dead, and then I would pray as well -- and still do -- for myself to become a good person.

Teach me to be humble,I would pray.And strong. Teach me not to sin.

Since we'd left the Midwest, I no longer went to church, because my mother had lapsed, she said, but still I prayed often. At the time I was also deeply afraid of becoming a pervert. Regarding sin, my priest would always say, winking, one hand feeds the other: it's the very nature of the beast, this self-abuse. And even though my priest was now over a thousand miles away, and my family was officially lapsed, every night I'd always resolve to become a decent man. Every night I'd say,Okay, this is absolutely the last time I commit a sin,and then I knew absolutely I had to be a pervert because it was impossible for me to stop even that: the evidence involved doing a lot of laundry -- mornings, before anyone in our dark house was yet awake, except for me and my dog. And then one day, doing the laundry, balancing my feet on the cool tile in front of the dryer, I became inexpressibly sad. I became sad because I knew I was damning my soul, repeatedly, to eternal and everlasting fire. That was why we'd moved to Arizona, I thought, exploring the idea: because here we were intended to be closer to the fire? In English I once read the nakedness of woman was the glory of God, which seemed right to me. Sometimes I got so sore it was hard to walk.

And then I really did stop. My father would have, I realized; so, too, would my Uncle Punch. Also one of my father's secretaries was barely twenty. At the funeral, while she was weeping, I could see part of her bra, and her pale skin, while she stood weeping at the grave site. She put her arms around me twice, once when my mother was particularly cold to her; the woman smelled like a vase full of flowers, like a garden, and I could feel her ribs beneath the fabric of her dress. Holding her, I wanted to be brave. I wanted to be still, and comforting, and always in the right; I also wanted her to love me instantly. Turning away, I pictured my father, someplace overhead, perhaps with a fine telescope, peeking down this girl's very blouse. My father, you see, understood perfectly the way a man was designed by God to behave.

So I stopped, aching loins and all, in order to prove to myself I didn't have to, as the saying goes, burn in hell. I simply stopped and thought about the twenty-year-old girl my father had seduced: lying awake, pretending, we'd have conversations, and sometimes I would rescue the girl from lions, or bullies. Once I even saved her by swinging on a rope from a burning three-flat and carrying her away in my arms. Each night, while falling asleep, this girl deep in my mind, I'd hope for one of those dreams which would let me wake up feeling all refreshed like a soap commercial. The thing about those dreams, which are wonderful, entirely amazing...the thing about a good dream like that is you never get one when you really want it. Instead you get one while you're camping with your friends, if you have friends, or when you've fallen asleep on the couch, and then there you are all sticky and damp and your dog Germs is digging away at your jeans -- beats me -- and your older sister's stepping out of the kitchen...your sister who just never happens to wear a bra, stepping into the family room, looking at you just that way and saying,Hey, have a nice nap?

My sister, Caroline -- because she was a woman, and older, when you looked into my sister's eyes, it was clear she knew more than most people. Among other things, she was soon to graduate and fluent in French and smoked cigarettes late at night. Sometimes she drank red wine. She was smarter than me, also lonely, and rail thin. And while it was she who once explained to me the biological function of those dreams --nocturnal emissions-- I knew as well some things foreign to Caroline's experience. I knew, for example, that sometimes when you have one of those dreams, the good kind, you never even see the person to which your body longs to be intended. Dreaming, you can be in a car, or a tree fort; you're dreaming about a blackbird, or a brand new saddle, the monsoons in your hair and then maybe you see a lock of hair belonging to a woman you might someday meet up with in a cafe, or on a sailboat, a twenty-two-foot sloop with an ocean nearby, a worn shoe washing up with the tide, and then that's it -- you wake up, all alone, perfectly refreshed and all a mess. In your dreams, at least, it is possible for a man to make love to more than just a human body: it is possible to love the essence, the very fact of these lives to which we hope someday to be introduced. And what drives you, always, is the idea of it -- longing, and the physical consequences of its release -- into the very heart of desire.

I didn't understand this then, only felt it; I didn't understand the miscibility of angels, and maybe saints, and ghosts. At school, two days later, still my first week after having transferred, I was walking to my morning class when some guy stopped his beat-up Camaro. I was late, of course, and seeing me, he called out in front of the school and pulled a U-turn, right there, the tires squealing. He stepped out, saying something to two guys in the backseat, and then he said to me, belligerent and clear, "Hey, ain't you the new faggot?"

At the time I didn't really recognize him. I could see his girlfriend, though, sitting in the front seat of the car. With his friends in the back, most likely he wanted to provide a good example. I said, calculating my options, dropping my voice into its deepest register, "Fuck you, sweetheart."

I was hoping for a tinge of Humphrey Bogart, who was also a fairly small guy. But now, of course, somebody had to defend some honor, regardless of whose, which also meant I was going to be humbled smartly, right here and on the way to school. And she's pretty, I remember thinking. She's pretty, this girl with the ribbons in her hair, sitting in his car...Pinski. Elizabeth Pinski...and she's sitting there, saying,Mark. Mark, I've got to practice. Come on, Mark...and there's ol' Mark, being a gentleman, saying,Hey, hey, it'll only take a sec, hon...and the next thing I know there I am sitting on the curb, my face in my hands and all full of blood, because, you know, if I weren't the new faggot at Gold Dust High School I'd know how to fight better. I wouldn't be getting the shit kicked out of me by some guy with a lower than C average old enough to buy beer. I'd have more testosterone, et cetera, and huge arms, and I'd pick a guy like that up by the neck and really thrash the son of a bitch. I wouldn't kill him or anything. I wouldn't want to have to feel guilty over that, too, later on, certainly not for eternity, and I wouldn't want to make his mom and dad feel bad, either, not just because some guy had thrashed their son who thought he was going to kick the shit out of some wimp who turned out, actually, to be a really tough son of a bitch who maybe even knew karate. Mostly I'd just scare him a lot, especially there in front of his girlfriend.

I'd say, "You should be nice to people who are smaller than you."

Of course, if Germs were there, my dog, he'd rip out the guy's entire throat.

Copyright © 1998 by T. M. McNally

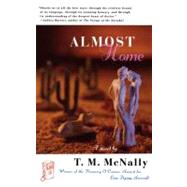

Excerpted from Almost Home by T. M. McNally

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.