Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

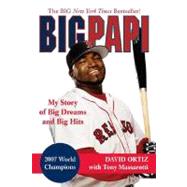

David Ortiz has averaged more than 43 home runs and 131 RBIs as a member of the Boston Red Sox, leading all major-league players in RBIs during the four-year period from 2003 to 2006. Ortiz has spent all or parts of ten years in the major leagues. In 2006, he hit 54 home runs to set a Red Sox franchise record, breaking the mark previously held by Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx.

Tony Massarotti began covering baseball in 1991 for the Boston Herald. He coauthored the bestselling book A Tale of Two Cities: The 2004 Yankees-Red Sox Rivalry and the War for the Pennant. He lives in the Boston area with his wife, Natalie, and their sons, Alexander and Xavier.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Excerpted from Big Papi: My Story of Big Dreams and Big Hits by David Ortiz

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.