Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Definition | 11 | (2) | |

| Introduction | 13 | (6) | |

| "The Lost Pilgrim" by Gene Wolfe | 19 | (26) | |

| "How the Bells Came from Yang to Hubei" by Brenda Clough | 45 | (12) | |

| "The God of Chariots" by Judith Tarr | 57 | (26) | |

| "The Horse of Bronze" by Harry Turtledove | 83 | (44) | |

| "A Hero for the Gods" by Josepha Sherman | 127 | (12) | |

| "Blood Wolf" by S.M. Stirling | 139 | (24) | |

| "Ankhtifi the Brave is dying." by Noreen Doyle | 163 | (32) | |

| "The God Voice" by Katharine Kerr & Debra Doyle | 195 | (16) | |

| "Orqo Afloat on the Willkamayu" by Karen Jordan Allen | 211 | (24) | |

| "The Myrmidons" by Larry Hammer | 235 | (16) | |

| "Giliad" by Gregory Feeley | 251 | (44) | |

| "The Sea Mother's Gift" by Laura Frankos | 295 | (24) | |

| "The Matter of the Ahhiyans" by Lois Tilton | 319 | (16) | |

| "The Bog Sword" by Poul Anderson | 335 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

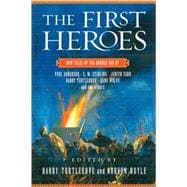

Excerpted from The First Heroes: New Tales of the Bronze Age

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.