What is included with this book?

| Preface | |

| Author's Note | |

| Acknowledgments | |

| Table of Contents provided by Publisher. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

The day the World Trade Center died was the kind of day it was born for, with the twin landmark towers outlined against a deep blue, cloudless sky. It had cost $1.5 billion, 200,000 tons of steel, 425,000 cubic yards of concrete, and six years to build the North and South Towers. They were designated Building 1 and Building 2 upon completion in 1972, the crown jewels of the sixteen-acre World Trade Center complex that included a twenty-two-story Marriott Hotel (Building 3); two nine-story office buildings (Buildings 4 and 5); the eight-story U.S. Customs House (Building 6); and a forty-seven-story high-rise office building (Building 7) that was home to the new command center of the city's Office of Emergency Management (OEM).

When the attack on 9-11 was over, both of the quarter-mile-high Towers and Building 7 had collapsed. The Marriott Hotel and Buildings 4, 5, and 6 were damaged beyond repair, and ten other buildings had sustained major damage. All that was left of the plazas, parks, and inspired architecture were pickup-stick piles of smashed concrete, jagged steel, and human remains -- the landscape of Ground Zero.

I was a lieutenant in the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD), a veteran officer with over fifteen years on the job, assigned to the Special Operations Command. The Port Authority had built the World Trade Center. It was our home. We had a precinct there. We knew it better than anyone. Maybe that's why what was important to me was not how quickly the Towers succumbed, but how long they survived. From the time each was hit by an almost fully fueled hijacked 767 commercial jet, the South Tower stood for fifty-six minutes, and the North Tower stood for one hour and forty minutes. That time enabled the Port Authority Police Department, the New York City Fire Department, and the New York City Police Department -- demonstrating bravery above and beyond under the most perilous conditions -- to conduct the largest and most successful evacuation in this nation's history, saving thousands.

Under other circumstances, I might have been a small part of the rescue and recovery operation at Ground Zero. Instead, I became the night commander of that mission, charged with recovering the remains of my fellow officers and the thousands of innocent victims killed when the WTC Towers collapsed. This is not my story alone. It is also the story of how the mission at Ground Zero transformed all the men and women who conducted it, and it is the story of how the Port Authority Police Department's profound desire to help the victims' families turned the most overlooked of all the uniformed services at Ground Zero into one of the most important.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was created in 1921 by the two states as an independent agency to oversee the harbors, presiding over a fifteen-hundred-square-mile area with the Statue of Liberty at its center. In 1930 the Port Authority was given control of the newly built Holland Tunnel. Using the tunnel's revenue, the PA went on to build the George Washington Bridge, the Outerbridge Crossing, the Goethals Bridge, the Bayonne Bridge, and the Lincoln Tunnel. In the late 1940s it leased Newark and LaGuardia airports and a small airfield in Queens that became John F. Kennedy International Airport. In the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, it built the Port Authority Bus Terminal; added a second deck to the George Washington Bridge; acquired the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, which became the PATH rail transit system; and built the World Trade Center, which it owned and operated for almost four decades.

Although the Port Authority Police Department protects almost every major air, sea, and land route in and out of New York and New Jersey; although we are visible at every bridge, tunnel, and airport; and although we have been in existence since 1928, when forty men were hired to guard the new bridges to Staten Island -- we are virtually unknown to the public. The PAPD? What is that? The Pennsylvania Police Department? The Perth Amboy Police Department? A standing joke held that this anonymity was why we had "Port Authority Police Department" spelled out on our uniform hats.

However, when the Towers collapsed on 9-11, the Port Authority Police Department suffered the largest loss of law enforcement personnel in United States history -- thirty-seven officers. The loss was larger than that sustained by the NYPD and a greater percentage of total force than that lost by the FDNY. The NYPD had 40,000 members, and the FDNY had more than 11,000. The PAPD had only 1,100. Every uniformed service death on 9-11 was tragic, but because of our size, not one single PAPD officer failed to lose someone close to him, including me.

On the morning of 9-11 I was at Children's Specialized Hospital at Mountainside when the call came in to mobilize. My wife, Karen, and I had brought our middle daughter, Tara, to undergo tests. Karen and I had been married for twelve years and had three daughters. Two were healthy. Tara was born with a little-known neurological disorder called Rett Syndrome. It occurs almost exclusively in girls. There is normal development for the first six to eighteen months of life, but then Rett Syndrome leads to severe disability by the age of three. At that moment, she was nine years old.

I tried to get through to our precinct at the World Trade Center on my wife's cell phone. There was no response from any of our desks. By now, every television in the neurology wing had footage of the burning WTC Towers. The newscasters kept talking about the buildings. I kept thinking about the people. How many had gotten out? How many were still trapped? How were we going to rescue them?

I drove Karen and Tara home and packed equipment and clothing for a long stay. I kissed Tara and my wife good-bye. Karen hugged me tightly. She was a cop's wife, and it was a certain kind of kiss. She knew what it meant: I was going into danger and had no idea when I'd be back.

Every highway with access to New York City was closed after the attack. New Jersey state troopers guarded the entrance ramp to the New Jersey Turnpike, and I had to show my Port Authority Police lieutenant's badge to get on. Apart from a convoy of ambulances and army trucks, my big old Mercury Grand Marquis sedan was the only car on the road. I pushed it past eighty miles an hour and headed for the PAPD command post at the World Trade Center.

At that speed the buildings of Jersey City, where I grew up, slid past me like snapshots. I saw the big Medical Center where most of Jersey City was born; Hudson Catholic High School, where from the windows of the third-floor lecture room we watched the Twin Towers being built across the river; the vegetable store on Sip Avenue where I used to see a then-unknown blind sheik named Omar Abdal Rahman holding court, never dreaming our lives would intersect when he tried to bring down the WTC in '93 and on 9-11 when his goal was realized; and I saw the candy store where we tried to figure out how the cranes on top of the towers could ever get down once they were finished building it.

Looking back, I can picture myself driving down the highway in my old Mercury as clearly as if it were a movie. I had the radio on. There were news reports of U.S. war planes in the sky and emergency vehicles arriving at the World Trade Center. Initial reports said there could have been as many as twenty-five thousand people in the Towers, and no one knew how many had been killed or injured. They talked about the attack on the Pentagon as an act of war, and there was constant speculation about the possibility of more attacks. The reports fueled the intensity of my need to get to the Trade Center to start helping. Duty called; I responded. People needed help; that was a cop's job. That morning, it all seemed so clear. Would I have felt the same if I knew the pain of the struggle I would face at Ground Zero?

At that moment I had no idea that the order mobilizing the Port Authority Police to the World Trade Center would mark the start of the longest, most painful, problematic, and rewarding journey of my life. I didn't know I would become the Night Commander of the World Trade Center Rescue and Recovery operation, or that I would spend every day of the next nine months in service to the families of the victims, or that in their service I would make decisions almost unthinkable at any other place and time.

No one at Ground Zero anticipated what the rescue and recovery mission would involve -- how it would change us or what we would feel the day it ended, when New Yorkers by the tens of thousands lined the streets to watch the Last Piece of Steel leave the site with hundreds of cops, firefighters, and construction workers marching behind it -- and I absolutely did not know what it would cost me to be leading them.

As I drove, I thought a lot about the World Trade Center bombing in 1993. It had injured more than a thousand, killed six, and left a crater two hundred feet wide and six stories deep, but the Towers stood. I was sure they would stand this time too -- burned but not broken, like in '93 -- until I heard on the radio that the North Tower and then the South Tower had fallen and ended all hope. My emotions couldn't accept the Towers in ruins. I had walked through the World Trade Center plaza when I was a kid on my way to Sy Syms to buy clothes. I tried to strike up conversations with the girls walking to work. The WTC was where I took my police tests and physical exams. It was where tourists and schoolkids and workers and people from all over came to sit down and see greatness. The images in my mind were of World War II cities bombed into rubble, except now the city was New York.

I got my first glimpse of the World Trade Center on the Turnpike Extension bridge over Newark Bay and driving down the Jersey side of the Hudson. Across the river there was nothing visible except thick black smoke covering Lower Manhattan like a coat.

I stopped at the Port Authority garage on the Jersey side of the Holland Tunnel, where a patrol car and driver were waiting to take me to the PAPD Command Post at the World Trade Center. In the Holland Tunnel Plaza there were rows of waiting ambulances, and army trucks with camouflage-pattern tops. The PA garage was a big space where we stored snowplows and heavy machines. It had been converted to a hospital. There were rows of white-sheeted cots with IV poles standing next to them. Doctors and nurses talked or made calls or inventoried supplies.

I took my gear over to the command center, which looked more like a store than a police station. I went through the glass doors into a waiting area with plastic chairs. The desk sergeant was sitting behind a Formica counter. He straightened a bit as I approached.

"Lieutenant Keegan? Sergeant Johnson. Your ride's on the way."

"Thanks, Sarge."

The TV on the wall showed nonstop footage of the Towers' collapse. No matter how many times the planes hit or the bodies fell, the sergeant kept turning back to watch it. He just kept shaking his head.

Outside in the plaza, cops and drivers and EMTs all moved at a normal pace. Where was the frantic tempo of an emergency? I expected shock and trauma. Instead the scene was calm and orderly. It was so different from the aftermath of the '93 bombing, when the rescue and relief work went on for days. The rows of ambulances and army trucks lining the plaza looked like bumper-to-bumper traffic except no one was going anywhere.

"Sarge, how long have these units been staged and ready?"

"Since right after the planes hit, Loo, but the Trade Center command hasn't called for a single one. Aren't there any victims?"

Like the rest of us, Sergeant Johnson expected conditions similar to those of the '93 bombing, when more than a thousand victims had needed emergency treatment. That early on 9-11, none of us yet knew how few of the WTC victims would need anything but burial.

"Ride's ready, Lieutenant. Good luck."

A blue and white PAPD patrol car was waiting outside in the plaza. The sergeant's eyes swiveled back to the TV screen.

I was anxious to get to the command post, but the few minutes it took the patrol car to drive through the empty Holland Tunnel were oddly peaceful. The peace disappeared as soon as we drove out of the tunnel into Manhattan. The smell of smoke flooded the car even through closed windows. Everything I could see -- parked cars, trees, storefronts --everythingwas covered inches deep in dust as if neglected for decades. There was paper too. Big pieces, scraps, pages of books, ledger paper, graph paper, legal paper -- all blasted from 220 stories of offices, banks, law firms, and trading companies by the collapse of the Towers.

We drove to the PAPD mobile command post parked on West Street in front of Borough of Manhattan Community College. I got out of the car and saw Ground Zero close up for the first time. The debris was four stories high across West Street. Returning cops and firefighters were walking back from it like soldiers after battle. Most of my cops were still in rescue gear, talking in small groups by the command post. Every inch of their clothing and gear was coated with cement dust. Their faces were completely white; the only color was the blue or brown of their eyes.

I was worried about them. They talked fast, disjointed -- what had happened to them, where they had been when the Towers fell, who else had been there. Some were vacant-eyed; we call it the thousand-yard stare. I had seen victims of violent crime stare like that, never a group of cops. I got to as many as I could, hugged them, talked to them, and comforted each as best I was able.

I went into the Command Post, a mobile unit the size of a bus that was dispatched from the PAPD's Journal Square headquarters in Jersey City. It was white and blue, the same colors as our patrol cars, with "Port Authority Police Department Mobile Command Post" on both sides in big blue letters. Inside, bulletin boards were secured to the walls. There were notices and information sheets tacked all over them. The unit had doors and windows in front and in back, and a center corridor with workstations with phones and computers on both sides. At the very end was the incident Commander's office. It had a special communications area and a conference table with bench seats.

Inside there was so much activity, you had to be an acrobat to get a cup of coffee back to a desk without spilling it. Specially trained technicians were hooking up phones, radios, and computers. Twice the entire command post rocked violently as engineers secured the steel legs that extended from the undercarriage to stabilize it. Inspector Joe Morris and his aide, Lieutenant Preston Fucci, were in discussions with senior officers. At the desks, officers were talking by phone or radio to our people here at the WTC and at other PAPD commands in and around the city.

At one desk, a special officer maintained the log. It was an important job. He logged in PAPD support teams arriving with everything from heavy vehicles to medical supplies, establishing a master list of the resources available to us. It was also the definitive chronology of events -- when the FAA ordered us to close the airports, or the Air Force began to do flyovers, or the FDNY declared a particular building unsafe and ordered everybody evacuated.

The PAPD faced serious problems on 9-11. The collapse of Towers 1 and 2 had destroyed our police precinct, our executive offices, our records, and our archives. Also, as a department we were stretched desperately thin. In New York and New Jersey, we were responsible for three airports, two tunnels, four bridges, the PATH subway system, two interstate bus terminals, and seven marine cargo terminals. Closing all the New York and New Jersey airports, all bridge and tunnel crossings into Manhattan, and the interstate highways into New York City was a huge job -- and the environment of heightened security only added to it.

I stowed my gear and checked in with Inspector Morris. In our command structure, captains and above -- inspectors, deputy chiefs, assistant chiefs, and chiefs -- are administration. Lieutenants are the highest rank of Operations. We are the most senior officers on patrol and are actively engaged in what police officers do. In the chaos of 9-11, the administrators were trying to identify the most serious issues. As a lieutenant, I developed plans to deal with those issues. I would determine what resources the plans required and then supervise the sergeants and police officers who executed the plans.

On 9-11 we lost our Superintendent of Police Fred Marrone, our Chief of Police James Romito, Inspector Anthony Infante, Captain Kathy Mazza, and many of our Emergency Service Unit officers. Not knowing the full extent of PAPD losses made it difficult to plan for what initial estimates said could be more than six thousand civilian casualties. It was a relief to everyone in the Command Post when one of our missing cops would radio in his or her location, or report to another PAPD command.

It became apparent to all of us that we had to get people back into position to move forward. I felt the most important thing was for me to get up to speed, to know what was going on. The only way to do that was to reach out to other commanders at the site. So I picked up a phone and started calling them.

Take a step forward, any step; what you don't know, you'll learn. That was how I approached the first few hours. I fielded phone inquiries from agencies wanting information about Port Authority operations at the airports, tunnels, and bridges. NYPD ESU Captain Yee called us asking to have PAPD officers assigned to his rescue teams to help them get their bearings on the site. The NYPD hadn't quite understood the WTC complex when it was standing. After the collapse they understood it even less. We were the only ones who could show them how to get down to the subways or to different parking lot levels or to where stairways had been located. That knowledge would play a vital role later on when I had to deal with the NYPD, FDNY, and their site commanders.

There were phone calls from upstate trucking companies with materials and equipment to deliver to the site. They had to cross the George Washington Bridge to get here, but it was closed. The only way we let them on the bridge was with a Port Authority Police escort that led them down to the site, or with an NYPD unit that met them at the bridge and brought them down. It was the same at the Holland Tunnel and the Lincoln Tunnel.

My initial intention had been to check in and go right down to the site, but I was too busy. Yet, as I was trying to make some kind of order out of all that confusion, a very small thing happened that showed me how much the wounds inflicted by the events of 9-11 had already changed our most basic perceptions of our lives and ourselves.

I was in charge of dispersing supplies from the staging area Inspector Larry Fields and Officer Barry Pikaard had established in the Borough of Manhattan Community College's big gymnasium to where they were needed. By midafternoon we realized we needed additional space for equipment that had to be instantly accessible to our guys, without request forms or protocol: items like Scott air bottles (the scubalike air tanks that fit into a backpack breathing apparatus), face masks, riggings, body bags, Stokes baskets (the stretchers with low sides used to carry bodies), helmets, and other emergency equipment. Our plan was simple -- set up big tents in front of the command post on West Street, which already had site security, including a view from inside via the external video cameras on its roof.

The problem was that West Street was lined with trees, and the tents were too large to fit between them. No one knew what to do. It became a problem. People began to redesign the tents; others looked for new riggings; others made calls to other services to see if they had tents smaller than ours. It became a debate involving nearly everybody -- until someone took a chain saw and cut down all the trees.

I had never even considered that. None of us had. Cut down trees to put up tents on a college campus in this city? Not usually, but given the horror we were dealing with, the stakes were simply too high not to do it. It was so small to be so big, but it was my wake-up call. We were operating under new and very different priorities.

A wide set of stairs off West Street led to Borough of Manhattan Community College's gym and the staging area. A conga line ran from the trucks in the street to the gym as people passed box after box of gloves, masks, shirts, flashlights, batteries, and helmets from one person to the next, all the way to where they were stacked and stored. On a walkway outside the gym, I saw my old friend Lieutenant John Kassimatis. I had once worked for John at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan. He was big and broad-shouldered, sporting an equally big mustache, and he was famous for his great stories about the "old times" at the Bus Terminal. John was enormously popular; no matter where we went, he always knew someone who greeted him like a best friend. I was with him one time when that included the Greek Orthodox patriarch.

John saw me and waved. He was on his Nextel phone, and I could hear his conversation as I got closer. It sounded like he was talking to his wife. It was the closest thing to normalcy I had heard all day.

"Yeah, I'm down here," he was saying. "You know, we're just getting some supplies . . . Yeah, no, I'm fine . . . I'm just gonna coordinate this, I'm not so sure what time I'll be home . . ."

It was the kind of mundane, everyday conversation that he'd had a hundred times about what time he'll be home, what he was doing, how the weather was and everything else. I liked hearing it. Then, in the middle of it, something came over John. His face changed. His voice too. It got deeper and sadder, and it was like there was something he couldn't hold inside any longer. He seemed to crumble a little, and said these words:

"I lost guys."

Those were the words, "I lost guys."Helost them. They were working forhimthat day.Hewas the boss. "I lost guys." It just didn't fit the conversation he had been having, so I knew how much he wanted to say it, to tell somebody. He said it once more, and then this big man with his big mustache and great stories bent over the railing and buried his face and his chin into his chest. I walked over to him. He was crying. I put my hand on his shoulder. He didn't react, but at least he knew I was there. That was enough. I stood to the side and waited, speaking, but not really talking, to the people passing.

After a while, John stood up and walked away.

I lost guys.

There was nothing else to say.

In situations like these, who knows why you gravitate to someone in particular? Outside, I found myself standing next to one of my sergeants, a wise old hand at the job, on the corner a little ways away from the others. He had just gotten back from Ground Zero and cleaned up a little and had some water, but he was still covered with ash. For a while we both stared down to the burning ruins of the World Trade Center. Around us, dust fell like snow. I knew from experience you can be in the command post all you want; only the people doing the job on the ground know what's really happening.

After some small talk, I found myself asking what I really wanted to know. I remember how the dust settling on him made his skin and clothes so white that when he turned his dark eyes to me and opened his mouth to speak, he looked like a photograph with too much contrast.

"How do things look, Sarge?" I asked.

He shook his head. "Not so good, Loo."

"Do we have any missing?"

"Yeah, we do."

"How many?"

"A lot," he said.

"A lot?"

"Yeah."

Every question was mine, repeated again as if I just couldn't get it.

"How many is a lot?"

"We don't know."

"Fifty?"

He shrugged. "Could be."

"More than fifty?

"Could be."

"How about the PATH guys?"

"A lot are missing."

It went on and on. Me asking, repeating his answers as questions.

"Missing? Like who?"

"Bruce Reynolds and Bobby Kaufeurs."

The names stunned me. Old friends. Good friends. I looked at him in disbelief.

"Reynolds and Kaufeurs?"

"Yeah."

Only later did I understand that our conversation evoked in me the same emotional and physical pain as the one I had in Children's Hospital in Philadelphia six years before, when Karen and I were first told about Tara. My daughter sat on my lap while they tested her -- find the doll, follow the doll, concentrate on the doll -- and even though I saw her fail the most rudimentary tests, I still wasn't ready for what happened to me when the doctor began telling us how she would need a special school. The truth was that as Tara had grown up, we had a growing awareness that something was wrong, but I had desperately avoided the truth. Even now I wanted her to pass the tests so I would not have to face it. I wanted it so much that I barely heard the words when the doctor spoke them.

"Your daughter is retarded," she said, and it broke my heart.

I got the same metallic taste in my mouth as when I was hit so hard on the football field that I got a concussion. The words drove me inside myself. When I didn't react, she said, "You understand, your daughter will never live outside the home."

I started talking just to get myself going, like a boxer punching even when he's out on his feet, punching just to keep on standing because it's all he knows how to do.

"Retarded?"

She nodded. "Yes."

"What do you mean by 'retarded'?"

"Her brain development is arrested."

"Arrested means stopped?"

"Well, there are levels."

"Levels?"

"It can be mild, severe, or profound."

"Which one is she, Doctor?"

"Severe."

"Severe closer to mild?"

"Closer to profound."

I had kept repeating what she said -- just as I was doing now on 9-11 talking to the sergeant on the corner, looking down to the site, watching the pile burn.

"How many?"

"A lot."

"How many is a lot?"

"We don't know."

"How about the PATH guys?"

"A lot are missing."

"A lot?"

"Yeah, a lot."

It broke my heart all over again.

The first lull in the action came late that afternoon. I had learned a lot about the overall situation from the other commanders, but it was time for me to head for Ground Zero. I needed to see the fallen buildings. I needed to take it all in. I had no specific plan. I'd know what was important when I saw it.

Wanting to see things clearly was a trait I inherited from my father. He was a captain in the Jersey City Fire Department, a man with very strong beliefs but still an independent thinker who analyzed things on their own merits. My father taught me that to make intelligent decisions, you had to "step back, observe, and remain objective." That practice helped me make decisions in the early days of my command at Ground Zero when there weren't any rules to guide us.

I learned something equally important from my mother -- the need to "temper justice with mercy." You can't be a really good cop without compassion and understanding. Sometimes you have to look at "extenuating circumstances." My father felt people should take care of their own problems. My mother was a wonderful woman, deeply concerned about the welfare of others and always involved in their lives. Two such different and distinct people had a hard time seeing, much less accepting, each other's point of view.

Maybe because I inherited aspects of each of my parents, I was able to love and appreciate both. I saw good in both. I suppose I was, and am, the fusion of both. Interestingly, living where we did in Jersey City between John F. Kennedy Boulevard and Martin Luther King Drive, the city's racial border, my parents gave me a real advantage. Even at eight or nine years of age, I could evaluate, appreciate, and communicate with just about everyone I met. Playing so many sports, I had to cross the "border" almost every day and interact with kids from all over the city. I saw that each side knew almost nothing about the other -- except fear. I saw how easily fear can become anger, and anger become violence.

It's not easy to be ignorant: you have to be taught. One of my parents' great gifts is that I wasn't.

With the action in the command post at its quietest level since morning, I finished up my work and gave my intended location to the desk sergeant. It was safer to go to the Trade Center site with a team, and I had already seen Colin and Mike Hennessy in the Command Post. Colin, the eldest Hennessy brother, was an NYPD cop. He had just finished his shift. Mike Hennessy was one of my top PAPD cops. I had been especially relieved when he reported in. They were Bronx Irish -- fair-haired, good-looking, tough, and athletic. Both were in uniform and had surgical masks hanging around their necks.

I went over and said, "Come on, I'm going down to the site. How about coming along?"

Colin shook his head, "Don't do it, Billy. Those buildings are gonna be coming down soon."

"Maybe they will, maybe they won't," I said. "But I gotta see what's happening."

I grabbed a mask and gloves and hung towels on my belt, like I saw a lot of returning cops do, to cover my face or any other exposed skin if necessary.

Mike had been watching me. He knew I wouldn't order him to go, and I couldn't order Colin because he was NYPD. Mike turned to Colin said something privately to him. Colin nodded and reached for his gear.

"You're not going alone, Billy," Colin told me.

"Hope that's okay, Boss," Mike said, suiting up too.

"It's fine," I said, and we headed out.

Outside, it looked like the moon. The dust on the ground was so thick it came up around our boots. It got even thicker as we moved toward the site. We reached a point where we had to get up on the cement medians along West Street to walk unimpeded.

The closer we got to the site, the more foreboding it felt. The streets were deserted. The evacuated buildings were dark. We couldn't see the sky, and when we reached Building 7, it was on fire. Building 7 had housed the Mayor's Office of Emergency Management along with financial institutions and government agencies like Salomon Smith Barney, American Express Bank International, the U.S. Secret Service, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Central Intelligence Agency. Now flames were spreading and smoke poured out of vacant windows that had been exploded by the heat.

We spotted a PAPD van abandoned in the street about a hundred yards from the entrance. We were still trying to locate all our people. The van might tell us which cops left it. If they hadn't been accounted for, we'd begin a search for them. I radioed in the number. Colin and Mike threw the van doors open and pulled out two replacement Scott air bottles and a PAPD airport command firefighter's bunker coat with its distinctive silver heat-resistant fabric andNIA-- Newark International Airport -- stenciled on it.

All this was extremely encouraging except for one thing: Building 7 started to collapse next to us.

There was a thundering roar like the sound of a dozen locomotives bearing down that got louder and louder as the forty-seven-story building crumbled only a hundred yards away. It stopped us dead in our tracks, paralyzing us because it seemed to be everywhere. The sound got even louder till it was almost unbearable. A dense black cloud was forming above St. John's University from the smoke pouring into the sky, towering over us. That did it.

Colin yelled, "Run!" and we took off for our lives.

It wasn't until we got maybe half a block away that we looked back. I'll never forget it. Up until that moment, I thought big things didn't move fast, but they did, and we were in trouble. That huge rolling cloud of black smoke and dust and debris from Building 7's collapse was coming straight up West Street at us like it was out to get us.

I heard the Command Post on my radio, "Building Seven is coming down. Building Seven is down." I was running too hard to respond. The only protection was the Command Post trailer ahead of us. The cloud rolled all the way up West Street. The wind reached us first. The three of us got to the Command Post and ducked behind it as the rest of the cloud hit us like a storm.

We were safe for the moment behind the trailer, but hunching there with the wind and dust and pieces of debris hitting all around, I knew Ground Zero was speaking to me personally. It had brought down a building right beside me to make sure I listened to its message:This isn't going to be like anything you've ever experienced. Be warned. Go back. It won't be like the first bombing. This is the real deal. You could die here . . . and if you're not careful, you will.

Copyright © 2006 by Keegan Corp.

Afterword

The legacy of the attack on the World Trade Center is far from over, and will never be complete until we recover the final remains we left behind. Neither will it be finished if we continue to let our workers and volunteers suffer and die.There can be no closure without real answers; there can be no real answers without the truth.The tragedy is that America knew it then, and is ignoring it now.

After the official closing ceremony, I was reassigned to another command on June 3, 2002. I refused to sign-off on the completion of the mission when asked to do so by the New York City Department of Design and Construction (DDC), the agency that managed the clean-up of the WTC site. Like many of the Ground Zero commanders, I maintained there were locations that might contain additional remains of the fallen that had not been properly searched. The holes in West Street caused by falling steel, and later just paved over, are just one example. It is clear that the DDC also knew that, but chose to end the mission for the sake of political expediency.

This serious charge is backed up by a May 24, 2002 memorandum from the Assistant Director of the DDC Environmental Health and Safety Service (EHSS) regarding the start of the EHSS team walkthroughs at Ground Zero. The memo states, in part:

Previous to our Wednesday 05/22/02 meeting, DDC-EHSS requested FDNY to submit those areas where recovery operations were completed.... Lt. John Ryan of the PAPD raised issues concerning the PAPD sign-off of the recovery areas of the EHSS Transition meeting.... These new sign-off arrangements would hamper the work of the EHSS Transition team, potentially delaying the sign-off by two weeks.

As you are aware, DDC and FDNY are the co-incident Commanders for the WTC Emergency Project. FDNY has the sole authority over issues concerning recovery.... [A]t this time I am instructing the transition team to immediately begin the walkthrough assessment so that we can avoid any further delay.

There are several problems with this memo. First, it is untrue that, as the memo states, "FDNY ha(d) the sole authority over issues concerning recovery." Although the FDNY was given command of Ground Zero on 9-11 because of its control over all "collapsed buildings" within New York City, shortly thereafter, the Unified Command structure that was ultimately put into place at the site gave equal authority over the recovery operation to the Port Authority Police Department, the New York City Police Department (NYPD), and the New York City Fire Department (FDNY).

Second, the "issues concerning the PAPD sign-off" refer to, and are a result of, a specific conversation I had with John Ryan that there were areas at Ground Zero we felt had not yet been thoroughly searched for human remains. Clearly, if these improperly searched areas were to reveal remains, it would take a lot longer than two weeks to complete the mission. The DDC figured that if the public knew there were still remains at Ground Zero, the site would have to be kept open months longer. But not closing the site would have put bonuses and new jobs for construction companies, and promotions for members of the DDC, in jeopardy.

The Memorandum never said the PAPD was wrong -- only that we didn't have authority to delay the intentions of the DDC. Such an obvious ploy by the DDC can only erode the victim family's confidence in the very people they depend upon for their answers. The families weren't given the truth about the extent of human remains still at the site.The New York Timesreports (Associated Press, December 7, 2006) over a thousand bones have been recovered during the past year, and the continued search for more remains will take at least another year. There are too many people who will never be able to move on as individuals or as a community because of it. Leonard Wong of the U.S. Army War College wrote, "While taking risks to recover the body of a fallen soldier may make no rational sense, it impacts significantly on the unit, the military profession, and US society." The creed is Leave No Man Behind. The victims of the World Trade Center attack deserve no less.

Those in charge of Ground Zero refused to do it the right way six years ago and still refuse to do it the right way today. I have had too many tearful phone calls from my former colleagues at the site say-ing simply, "Loo, how did we miss all this?" I can only tell them that, along with the families, our hearts were broken, too...and that we did our best but were prevented from doing all.

It is the same with the health and safety of the workers and volunteers at Ground Zero. Six years after 9-11, I have had to come to grips with the fact that my future is at best uncertain -- and the terrible irony is that I am one of the lucky ones.

The Ground Zero environment contained debris contaminated by 26 miles of Mercury lighting, 6 million square feet of concrete dust, thousands of tons of plastic and asbestos. Wood, metal, plastic, jet fuel, and many other substances that were present in the debris at the site released toxic fumes as they burned. Mercury vapor is a neurotoxin. Yet workers who showed high levels of mercury in their blood were given only brief respite, and then reassigned to the site. Since November 2001 I have experienced sinus infections, headaches, and eye irritations. In August 2002, I developed a nerve weakness in my neck, back, and shoulder that left my right arm nearly powerless -- and I am not alone.

According to the September 6, 2006,New York Timesreport on the results of the health study released by doctors at Mount Sinai Medical Center, the largest study yet of the thousands of workers who labored at ground zero(Illness Persisting in 9/11 Workers, Big Study Finds,by Anthony DePalma): "the impact of the rescue and recovery effort on their health has been more widespread and persistent than previously thought, and is likely to linger far into the future.... Roughly 70 percent of nearly 10,000 workers tested at Mount Sinai from 2002 to 2004 reported that they had new or substantially worsened respiratory problems while or after working at Ground Zero.

"The study is among the first to show that many of the respiratory ailments -- like sinusitis and asthma, and gastrointestinal problems related to them -- initially reported by Ground Zero workers persisted or grew worse in the years after 9/11.

"The New York Timesreported that most of the Ground Zero workers in the study who reported trouble breathing while working there are still having those problems up to two and a half years later, an indication that the illnesses are becoming chronic and are not likely to improve over time." Some of the workers worked without face masks, or with bandannas, when what we needed were full-face sealed respirators, or the Bio-Hazmat suits which workers are using now.

"There should no longer be any doubt about the health effects of the World Trade Center disaster," said Dr. Robin Herbert, codirector of Mount Sinai's World Trade Center Worker and Volunteer Medical Screening Program. "Our patients are sick, and they will need ongoing care for the rest of their lives."

Beyond their physical ailments, many of the rescue workers and volunteers who were at Ground Zero remain isolated and disconnected from their families, alienated from former friends, and unable to reestablish their place in society. In short, countless thousands of men and women who gave "above and beyond" are suffering. Dr. Charles L. Robbins of the Stony Brook University School of Social Welfare states "former WTC workers are experiencing significant health problems manifesting in all body systems and organs, including stress disorders and emotional disturbances, caused by their exposure at Ground Zero." For some, the pain is unbearable because the immensity of their effort has been met by a public denial of their pain, creating an isolation which is the root cause of a rising rate of suicide. During the event, no sacrifice was too great. Now that ethic has set the scene for another disaster, unfolding today.

Dr. Spencer Eth, vice chairman of psychiatry at St. Vincent's Hospital and professor of psychiatry, New York Medical College reports:

The St. Vincent's World Trade Center Healing Services have seen over 50,000 people who were psychologically affected by 9-11. Many victims have needed to remain in treatment for years. Our efforts continue because the suffering continues; and although fewer people are seeking help for the first time, those that are tend to be especially distressed and disabled, including uniformed service personnel, including firefighters and police officers. Tragically, almost all of the funding for these special programs has been terminated. That should not be allowed to happen -- effective psychiatric treatment must be provided -- or we may be forced to witness additional suicides and misfortune borne by the true heroes of the World Trade Center disaster.

On a daily basis I talk to my men who worked at the site and I bear witness to the number who are close to suicide, or who are simply going through the motions of life as shadows of the men they once were. Last week we buried a fine man, a husband and father, a former Marine, and a decorated veteran Port Authority police officer who jumped off the George Washington Bridge because the pressure building since the mission at Ground Zero finally proved too much to bear. There have been more than half a dozen PAPD suicides since the rescue and recovery mission at Ground Zero -- and 25-year PAPD veterans can't remember a single suicide prior to it.

The recovery mission changed us; ending it changed us again. Life after has never been the same. Many still search for the certainty of purpose and place we found here. That emptiness was never properly addressed. When we left the site many of us were brought to an upstate hotel for a "debriefing." The intention was admirable but the result was woefully inadequate. I completed over 220 tours of duty at Ground Zero and I was interviewed by a volunteer for a private organization with less than 16 hours of "training" who had never even been to the site.

It doesn't matter who is to blame for the past. What matters is who is accountable for the present. We who worked at Ground Zero are still denied even the acknowledgement of our conditions. I am sick of hearing how complex the solution to our problems has to be; it isn't -- not if we educate the public about the plight of those who served at Ground Zero concerning the isolation and denial which are the root causes of the stress disorders and suicides that have followed.

We must provide free medical screening and care for all those who worked at Ground Zero and their families. We must create a mechanism within a federal agency that immediately establishes a baseline medical data bank for all workers in mega-disaster situations, with blood and tissue samples taken on a regular basis. A coalition of federal and state officials must establish an independent commission for responders and recovery workers similar to the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund. A no-fault alternative to lengthy tort litigation, the 9/11 Victim's Compensation Fund was initially received with skepticism but proved successful in allowing families to move on with their lives. If we do not allocate the time and resources needed, the ghosts of those who have died, and will die, because of it will haunt the building built on what became their graveyard.

The men and women who worked at Ground Zero rose to the greatest challenge of our lives. We fought the first part of the battle without a single fatality or serious injury to a worker and the startling fact is we have lost more workersafterthe rescue and recovery than during. The dust we cleaned up is still choking us. If we can sit back and watch that happening without taking action we are not the America we say we are. That America would not leave those who have sacrificed for their country in harm's way; would not leave them to fend for themselves; would not ignore compassion and look away pretending everything is okay. That America would not use accounting principles instead of medicine, for when the call comes again -- and it surely will -- who will respond if we teach our children that America turned its back on those who did what was asked of them?

Copyright © 2006 by Keegan Corp.

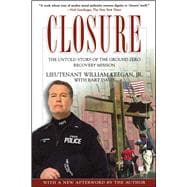

Excerpted from Closure: The Untold Story of the Ground Zero Recovery Mission by William Keegan

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.