What is included with this book?

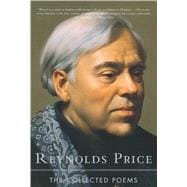

With his novel A Long and Happy Life in 1962, he began a career which has produced numerous volumes of fiction, poetry, plays, essays, translations and memoir. A Long and Happy Life won the William Faulkner Award; Kate Vaiden won the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction; and his poems have won the Levinson, Blumenthal and Tietjens awards from Poetry.

He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and his books have appeared in sixteen languages.

CONTENTS

Preface

I. VITAL PROVISIONS

(1982)

ANGEL

ONE

THE DREAM OF A HOUSE

THE DREAM OF LEE

THE DREAM OF FOOD

SEAFARER

QUESTIONS FOR A STUDENT

THE ALCHEMIST

AT THE GULF

LEAVING THE ISLAND

ANNIVERSARY

ATTIS

BETHLEHEM -- CAVE OF THE NATIVITY

JERUSALEM -- CALVARY

PURE BOYS AND GIRLS

NIGHT SPEECH

TEN YEARS, FOUR DAYS

RESCUE

TWO: NINE MYSTERIES

ANNUNCIATION

REPARATION

CHRIST CHILD'S SONG AT THE END OF THE NIGHT

DEAD GIRL

NAKED BOY

SLEEPING WIFE

RESURRECTION

INSTRUCTION

ASCENSION

THREE

PICTURES OF THE DEAD

II. THE LAWS OF ICE

(1986)

PRAISE

ONE

AMBROSIA

WHAT IS GODLY

GOOD PLACES

TWO : DAYS AND NIGHTS

PREFACE

THREE

LINES OF LIFE

THREE SECRETS

III. THE USE OF FIRE

(1990)

ONE

UNBEATEN PLAY

SOCRATES AND ALCIBIADES

THREE DEAD VOICES

TWO: DAYS AND NIGHTS 2

PREFACE

- 1. NAZARETH, MARY'S HOUSE

- 2. BETHLEHEM, BIRTHPLACE

- 3. CAPERNAUM, PETER'S HOUSE

- 4. GETHSEMANE, GARDEN

- 5. JERUSALEM, JESUS' SEPULCHER

- 6. MOUNT OF OLIVES, ROCK OF THE ASCENSION

THREE

JUNCTURE

YOUR EYES

LOST HOMES

IV. THE UNACCOUNTABLE WORTH OF THE WORLD

(1997)

ONE

AN ACTUAL TEMPLE

NEW ROOM

THE DREAM OF THE COURT

FIRST CHRISTMAS

LEGS

THE DREAM OF ME WALKING

MID TERM

ALL WILL BE WHOLE

ENTRY

TO MUSIC

TWO: DAYS AND NIGHTS 3

PREFACE

THREE

THE DANCING AT CANA

THIS FIELD

ANOTHER MEAL

THE LIST

FROM SO FAR

A HAVEN

THE DREAM OF MOTHER AND MY CANE

THE BUDDHA IN GLORY

SCORED BY LIGHT

THE PROSPECT

THE CLOSING, THE ECSTASY

Acknowledgments

Index of Titles

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

I was twelve years old when I began to encounter poems more demanding than the jingles of childhood or the nonsense lyrics of popular songs. Those first serious poems were introduced to me and my colleagues in a seventh-grade public-school classroom by Jane Alston, our teacher. She was an imposingly tall, middle-aged and never-married woman of dauntless gravity and rare but keen delight; and she was generous with praise when surprised by a sign of thoughtful imagination from her students. A superb sergeant for our maneuvers through arithmetic, reading, geography and natural science, she possessed as well a simple method which I've never met with elsewhere for building poetry into young human bones.

From a slender volume calledBest Loved Poems,she'd read us a favorite of her own -- brief lyrics from poets of genius like Wordsworth, Keats and Tennyson and from lesser but often rousing lights like Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Longfellow, Whittier, Eugene Field and John McCrae. Then she'd write the day's poem on the blackboard for us to copy into our notebooks (the copying became, simultaneously, an exercise in the now lost art of legible penmanship). Every few days Miss Alston would lead the class in reading, aloud in unison, all the poems we'd copied. Occasionally she'd have us copy the words of a well-known song, and we'd add a cappella musical renditions to our repertoire -- the song that's haunted me longest is the Scottish "Annie Laurie" (a majority of my classmates had Scottish roots, as I do). The vigor and swing of those performances suggested that far more members of the class than I had discovered a welcome new form of play. And given our widespread enthusiasm and the porous eagerness of young minds, we likewise found that in a matter of only a few such performances, all the poems were locked into place in our heads.

In my case, most of them wait there still; and on numerous occasions of boredom, fear or foundering spirits, I've brought them forward for silent assistance. Mostly when I call them to mind, I feel again the rise of my boyhood zeal, a pleasure which can suddenly flow from the presence of that benign conjunction of word, image and rhythm which poetry offers more liberally than other forms even in lines of a minor distinction like those I first learned in 1945 (from John McCrae's "In Flanders Fields") --

Take up our quarrel with the foe;

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Some three years after that introduction, I made my first independent contact with a poet who -- though she'd been dead for sixty-two years -- would lure me to study all the available work of a particular lifetime. That contact was made not only in independence but in solitude and apparent coincidence. It was in 1948; my family had recently moved from a town with no bookstore to Raleigh, and the capital city boasted two stores which offered a secular stock. Though they maintained a pitifully small range of new titles, each offered a shelf of inexpensive Modern Library editions.

Early on I'd acquired two schoolboy favorites,The Prophecies of Nostradamusand W. H. Hudson'sGreen Mansions;but one gray Saturday afternoon when I was fifteen, I chanced onThe Selected Poems of Emily Dickinson.I doubt I'd heard Dickinson's name till then; and I was unaware that her nearly two thousand poems had still not appeared in a chronologically arranged and textually faithful edition. But on that lucky afternoon, as the small selected volume fell open, I read to myself

Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne'er succeed.

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

Not one of all the purple Host

Who took the Flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear of Victory

As he defeated -- dying --

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Burst agonized and clear!

The fact that I was only beginning to emerge from a gloomy stretch of early adolescence -- one that had left me feeling powerless and defeated among my contemporaries -- meant that I was ideally braced by temperament, recent experience and a still uncrowded sensibility for such a rich discovery. With a sharp clarity, I recall the inexplicable elation of that moment as one of the two or three high points in a lifetime's reading.

I bought the book, read Conrad Aiken's preface that night and gradually consumed the remainder of the poems over coming weeks. The childhood rhymes and radio songs and the memorized poems from Jane Alston's class had entered my mind as all but inhuman objects. They'd felt more like tangible specimens for my growing boy's museum -- with Indian arrowheads, stamps and old coins -- than like durable forms of help from another member of my species. Dickinson's poems were the first that struck me as not only important and memorable in their own mysterious right (and without the prior endorsement of my teachers); they were also my introduction to the idea that a particular solitary human being might actually make such practical and lasting objects -- someone who, in Dickinson's one surely attested photograph, looked much like any number of my distant cousins or teachers.

Again I committed many of the poems to memory; I consulted other editions; I read biographies of Dickinson, wrote a poem of my own about her, made her the subject of my junior-year term paper for the American literature class taught by a fervent apostle of poetry named Phyllis Peacock; and I delivered a lengthy presentation to my classmates on the phenomenon of Dickinson's lone brave existence and the wealth she made of it. Never quite saying so to a group of contemporaries who were visibly ready to lunge into laughter at any whiff of pretense, I managed to get away with implying for myself a degree of privileged kinship with this woman and the body of her work. Even in the presence of Dickinson's most opaque riddles, after all, I'd mostly sensed that I penetrated her veiled sanctuaries through a near-blood bonding. (Interestingly, in the upper South of those years, none of my classmates seemed to find anything strange in Dickinson's withdrawal from society -- few extended families then lacked their own eccentric but tolerable aunt or cousin, usually a widow, spinster or bachelor.)

Privately I'd also begun -- as eros swamped me in its first riptides -- to guess what depths of transport and darkness lurked at the edge of even the most sequestered human mind, one that demanded such a broad range of response from itself. What acts, mental or physical, could have lain for instance behind Dickinson's consumingly erotic

Wild Nights -- Wild Nights --

Were I with thee

Wild Nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile -- the Winds --

To a Heart in port --

Done with the Compass --

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden --

Ah, the Sea!

Might I but moor -- Tonight --

In Thee!

Led on in the hunt for comparably successful shocks, by the time I entered the final year of high school, my battery of favorites had expanded to include a few prose works --Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina,the early stories of Hemingway and hisA Farewell to Arms-- but for a good while, nothing equaled for me the poems and plays of a still-writing contemporary, T. S. Eliot. That attraction developed even as one of my senior teachers guided me in another direction by showing me her autographed copy of the poems or A. E. Housman, whom she'd met in the thirties on a trip to Cambridge. In part, my curiosity about Eliot was kindled by the unprecedented public attention paid to him in the wake of his Nobel Prize (1948) and the immediately subsequent success of his playThe Cocktail Party.No other poet writing in English since the dazzling youth of Lord Byron can have had such fame and attention as Eliot received in the late 1940s and 50s. Another part of my own early fascination lay, as it did for legions of older readers, in Eliot's notorious obscurity -- poetry as puzzle can be as riveting a game for a bookish child as it was then for thousands of scholars.

But I also know that the seeds of a lasting debt were sown in my first baffled readings of "Sweeney Among the Nightingales" and "The Waste Land." Those seeds lay in a boy's dim perception of the unfeigned and luminous awe which poured -- in verse of such bare strength -- into Eliot's middle and late work from his passionate but long-chilled hunger for transcendence. From my first encounter with the work, it struck an unlikely harmony to already-old longings in me; and from that time on, the mind and the piercing voice of Eliot's eerie unaccompanied quest were my close companions. Few months have passed in ensuing years in which I have not read one or more of theFour Quartetsor heard them in Eliot's fierce, though desiccated, voice on his recordings.

Toward the end of my freshman year at Duke University, I encountered yet a third poet who'd soon blank most others in my study and pleasure. In an introductory course of Major British Authors, I first read quantities of the work of John Milton. A few years earlier I'd heard the sonnet on his blindness over the radio, but I knew little else about him. So launching at the age of nineteen into the swirl and swagger of his "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity" (written to celebrate his twenty-first birthday) and, above all, his grieving "Lycidas" had the overwhelming and hallucinatory effect of a month spent prowling the floor of the sea -- somehow safe but rapt in the effort to absorb and retain every sight and sound for the later hours when I'd surface and could sort my findings.

In my sophomore year I enrolled for a semester's work in Milton with Florence Brinkley, a respected scholar of seventeenth-century English poetry and another Southern spinster who combined the iron strength of her devotion to poetry with a quizzical social mildness that reminded me of so many of my earlier teachers and made her both an intimate guide and a chaste but oddly radiant priestess. My engagement with Milton's early poems continued -- and a sense of kinship, however distant, with Milton's awareness, from his early school days, of high vocation as a poet and teacher -- but months of gradual immersion inParadise Lostwere like an obsessive love affair or a low-grade fever that refused to remit in its heightening of my senses: above all the mind's love of thought and its relish for language deployed with the strut and potency of grand architecture yet the translucent line of the simplest ballad.

Toward the end of that term, Miss Brinkley urged me to read a book calledPoetry as a Means of Graceby C. G. Osgood. Conceived in 1940 as lectures to young Princeton theologians, Osgood's still keenly provocative chapters propose that, in a hectic and book-filled world, a thoughtful person might well choose a single inexhaustible poet and fix upon that poet's work as a lifelong spring of refreshment in the driest times. From his own obviously immense knowledge, he suggests four candidates -- Dante, Spenser, Milton and Samuel Johnson -- and proceeds to define the offerings of each. Of Milton he concludes,

...I know him as an older friend and brother from whose presence I never depart without a sense of expansion, and enlargement, of clarification of mind and accession of power, together with an exaltation of spirit.

Still short of twenty, I harbored suspicions about the source of grace that were fairly unshakable, but Osgood's old-style avuncular tone deepened and clarified my attraction to Milton. Neither Osgood nor Miss Brinkley were the first sane persons I'd known who freely confessed that poetry -- even the poetry of others -- was worth a whole life; but there beside the lifework of Milton, they made their point convincingly and permanently.

The giant battery of Milton's skills, his fevered steady drive to know and consume and present all life, from ant to seraph, in its native splendor fired my own diffuse will to write; and the polyphonic richness of his language, with its ready access to the eloquence of plain speech, rang familiarly in the ears of one raised, as I'd been, in a society all but drunk on its craving for a spoken and written language equal to the coiling emotional and moral needs of a life as complicated as that of my own kin and friends in the upper South, less than a century after a devastating war we'd conceived for an evil purpose. Milton's voice, after all, rose from the same Anglo-Celtic-Norman springs that had shaped -- with beneficent African additions -- the tongue and tone of my home place. The demands and rewards of that voice continued to hold me through a further Milton course at Duke with the doughty Allan Gilbert, through a senior thesis on Milton's entry into public life, then a graduate thesis at Oxford on his dramaturgy (with the formidable Helen Gardner, a guide whose unpredictable compound of gentleness and rigor most usefully echoed Milton's vehement amiability).

By the end of three years in the now-lost England of the 1950s -- an England much like Milton's own -- my early allegiance to poetry had been hammered into what would amount to a sleepless, if sometimes distant, companionship. And for all my growing interest in the writing of prose fiction, I'd begun to suspect that I was also fitted with a hunger for the small and large satisfactions that appeared to be offered only -- in the English language at least -- by the audible human voice as it creates or reproduces in verse one of an infinite variety of thoughts while that thought forms itself into words and is simultaneously formed by those words, by that rhythm and all the other possibilities of verbal music: rhyme, assonance, dissonance, modest plainchant and incantatory ecstasy.

Full attention to the hunger would wait through more than an otherwise busy decade. Meanwhile, none of those concerns interfered with my having a normal young life of laughing friendship with my friends, my first reciprocated loves, domestic duties and the eventual and ominous necessity to choose a profession and earn both my own keep and a share of my mother's (my father had died when I was a junior at Duke). Meanwhile, I was generally lucky in having friends my own age who were struck with similar compulsions. Our long talks prompted me further; and soon like many of them, I'd begun to eke out attempts at poems of my own. A sizable handful of those efforts survive. They cast me, more than a little melodramatically, as the loneliest soul on the planet yet one prepared to gamble on the power of language to bridge most gulfs if the words are got right.

Of those brief poems, none is right enough to offer here, even as juvenilia. The earliest included are "The Sleeper in the Valley" after Rimbaud and "I Say of Any Man" after Hölderlin. Small as those two versions are, they were not completed until 1961 after more years of formal and informal study -- I was then twenty-eight. And perhaps, since they came shortly after the completion of my first book, a novel, the long span of focus on prose narrative had silently demonstrated how much of my life was likely to prove of no use to my fiction.

It would be misleading not to acknowledge that such a late beginning came after the gradual encouragement of a few exemplary practitioners. Among them, in my early adult years, Robert Frost was frequently available in public readings and for one memorable small seminar in Chapel Hill. W. H. Auden was among my teachers in graduate school, at a time when I was immersed in continued study of Milton. Shy, though hilarious and profoundly instructive, Auden sought out those of us with an interest in the writing of poetry and -- with no insistence whatever -- became at once an enduring example. Stephen Spender published my first fiction inEncounter,a journal which he was then coediting, and for the remainder of his long life was the source of unabashed advice, keen-eyed warning and generous friendship. His own seven decades of work have proved an invaluable guide to the outer reaches of a poetry of unrelenting self-inspection.

The other poems collected here have gathered in the nearly four succeeding decades -- sometimes in rapid clusters, sometimes sparsely and with lengthy pauses. Through most of the 1960s and early seventies, my energies continued to concentrate on the writing of more novels, stories, plays and essays. Yet my reading and teaching kept the prospect of poetry clear before me, however distant (I'd begun to teach the thoughtful reading of prose and verse at Duke University in 1958); and a new poem sometimes made its way through the prevailing prose -- generally a short poem that meant to preserve some small incident which seemed in imminent danger of vanishing if not reproduced quickly in the most precise sentences available.

It was only in the late 1970s, however, that I found myself more and more subject to the arrival of poems and to the eventual awareness that many of my experiences had begun to present themselves in the shapes and tones of verse. I suspect that the gradual ambush of middle age had much to do with the development. A certain kind of person, made keenly aware of growing age and mortality, is likely to find himself in search of a means to fix those maybe significant memories that become increasingly fugitive or less inclined to merge into the longer colonnades of prose fiction and memoir.

Then in the mid-1980s, when I stalled in the straits of an illness that refused to admit more expansive work, I turned frequently toward the drafting of short poems. Most of them were composed for a notebook or journal, calledDays and Nights,which I'd begun to keep only a few months earlier. Though work in that notebook has continued till now, I've by no means written for it daily. Still its steady presence on my desk has allowed me to secure, in stripped-down but occasionally fuller poems, a few striking aspects of random experience which might otherwise have faded from my memory.

Those poems outside the journal differ markedly in their occasions, and their procedures have varied considerably through a working span of thirty-five years. The first three-quarters of this collection comprise the contents of three earlier volumes --Vital Provisions, The Laws of IceandThe Use of Fire.Anyone familiar with those collections will note that there are no omissions here. However tempted I am to reprint only those poems that attain their full ambition, it has finally seemed preferable to persist in laying out the broad spread, not a tidied or camouflaged garden. The few original poems that occur in my volumes of fiction were written, or adapted, for the needs of a particular character and situation and are not included here; several poems published in journals but not previously collected are again excluded as unsatisfactory.

There is also, in previously published work, only the barest minimum of correction (the temptation to realign a few early heavily stressed passages into what now seems a more natural metrical order has been resisted; punctuation and spelling have not been homogenized; and at the risk of repetition, I've retained in my notes to the first two parts ofDays and Nightsa few matters that are dealt with more amply here). An obligation in being a writer of any sort, as of being human, is the owning up to the final outcome of one's range and choices. I've long felt that, once a poem has made its initial appearance in a book, it has ceased to be the author's creature to change at will. However small its audience, the poem has entered public life and almost surely cannot be profitably changed by its author, a person who has gone on to become someone else. Modern poetry is rife with examples of poets who have deformed good early work through later revision -- Whitman, Yeats, Ransom and Auden are prime examples and have served as warnings against the occasional itch to smooth an earlier roughness or a hapless vulnerability. So I have not only resisted substantial change, I have left in place the initially unconscious repetitions of word and image that become in time one more form of confession.

I have likewise retained, and augmented, a scattered body of poems which are American versions of poems by writers in other languages. Since some of those poems have occurred in languages that I barely know, if at all, I discovered many of them in translation and have resorted freely to literal-sense versions made for me by knowledgeable friends and scholars. In every case, my versions and variations were made from poems that -- so far as I comprehended them -- were relevant to live concerns of my own. That the versions are often so free as to constitute scarcely recognizable variations is no less a gesture of homage to their originals.

The most literal transcriptions in the volume are grounded in another source -- the intimate yet alien nightly dream. All but one of the poems entitled "The Dream of [So and So]" -- or, in one case, "Lion Dream" -- reproduces as faithfully as possible a dream I experienced, one that seemed of more weight and interest than the average run of my nocturnal narrative sessions and that I transcribed no more than a few days later. ("The Dream of Me Walking" reproduces a frequently reported dream of my friends.)

The final quarter of the volume, entitledThe Unaccountable Worth of the World,consists of new and previously uncollected poems, including a third substantial group from the ongoingDays and Nights.Though the new poems sketch a few comic gestures, the fact that many concern themselves with the deaths of friends is not so much a function of a darkening turn of mind as it is the natural result of my age. I was born in 1933; my contemporaries have begun to fail and die with some frequency; and the AIDS disaster of recent years has, with monstrous cruelty, taken younger friends. A number of new poems expose the same elations and quandaries of desire and need as my earliest poems of isolated boyhood. That longing, however, has now lost much of its power to humiliate, coming as it does as a welcome sign of life.

From the start -- perhaps in an unconscious effort to establish independence from the pentameter of Milton and so much other early reading -- many of the poems are linked by a family resemblance in their tendency to volunteer in the oldest of English-language rhythms, the relentlessly powered four-stress line ofBeowulfand other Anglo-Saxon survivals: a line in which the number of syllables is relatively immaterial and may be widely varied. Though my own poems have mostly come without the heavy Saxon regularity and alliteration, my version of the Old English poem "Seafarer" attempts to recall that propulsion and those hammering echoes at their ancient height. Earlier and elsewhere, Samuel Taylor Coleridge found the same line productive of a natural but heightened diction. In 1815 in the preface to his poem "Christabel," Coleridge defended his revival of an apparently irregular meter with the claim that "this occasional variation in number of syllables is not introduced wantonly, or for the mere ends of convenience, but in correspondence with some transition in the nature of the imagery or passion."

I've mentioned that a few of my early poems attempt to insist that the reader employ a high degree of accentual emphasis. Elsewhere, my less insistent versions of the four-stress rhythm rely on a choice of systolic variations in speed; and close attention is given to line endings and enjambments in the hope of avoiding an unduly po-faced plainness. A number of poems have arrived with other rates of stress and regularity, and a few have come with no predictable meter. But the four-stress rhythm -- since it is seldom prone to the prolixity that threatens longer lines and since it allows for unanticipated moments of emphasis on a varying ground of syllables -- has felt closely allied to the wary economy and dignity of those kinds of speech that, in my lifetime, have been most concerned for lucid and memorable communication with sundry but alert listeners.

Subject as the four-stress line is to shortening or lengthening, that intense and often eloquent native speech frequently offers, in its robust candor, to make a last step into narrative verse. More than many of my American colleagues, I've distrusted the lyric poem which is not braced on an armature of tellable story (the stride of narrative being a born dispeller of the clandestine and hermetic). My continuous effort has been to assist that last step onward from speech into comprehensible and useful story; and I've tried to remember that even narrative verse must work to be as well written as good prose, as detaining as good talk and no more subject to private quirk than any other would-be communicative act.

Finally, I note that my allegiance to poetry and my hope to write it were formed in a physical, human and artistic world very different from today's. While I continue to read some contemporary poets with enjoyment, the work that caught my attention early, and goes on holding it, was and is the work of Dickinson, Eliot, Frost, Housman, Milton, Herbert, Donne, Wordsworth, Keats, Hopkins, Yeats, Rilke, Rimbaud, Auden and Robert Lowell (I name them in the order of encountering their poems). In its concerns and results, my work is patently different from any of theirs; but their examples of self-reliance, sleepless curiosity about the world and its creatures, and an insistent concern to be heard and remembered have remained strong standards for me.

Though my young interest in poetry coincided with the late phases of the arch high-modernists, my own poems are often skeptical of the modernist demand thatMake it newbe the banner aim of poetry. It has often seemed to me that a more productive aim might beShow it old and vital;and a few poems here have the express aim to echo, while revising, older but still rewarding voices. If occasional other poems and lines have the air of a former time and idiom -- if they take a wider view than is presently common of the desirable range, altitude and depth of poetic subjects and of the instruments by which those subjects may be observed -- then that air is not necessarily the result of conscious archaism, verbal exhaustion or rampant nostalgia but of the deep-cut impressions of youth, of youth's most durable alliances, and of the actual timbre of a voice formed in an earlier school of what is believed to be reliable and perennial language.

R.P.

Copyright © 1997 by Reynolds Price

Excerpted from The Collected Poems by Reynolds Price

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.