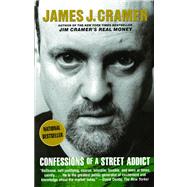

What is included with this book?

| Early Years | p. 1 |

| Goldman | p. 23 |

| Money Man | p. 40 |

| Building a Hedge Fund | p. 58 |

| SmartMoney | p. 66 |

| The Birth of TheStreet.com | p. 83 |

| Dow Jones Again | p. 99 |

| Desai | p. 106 |

| The Man with Two Careers | p. 123 |

| Media Man | p. 139 |

| Cendant | p. 146 |

| Berkowitz | p. 155 |

| The Hiring of Kevin English | p. 163 |

| Crisis in 1998: Part One | p. 169 |

| Crisis in 1998: Part Two | p. 195 |

| Crisis in 1998: The Trading Goddess Returns | p. 218 |

| Inside the IPO: Part One | p. 238 |

| Inside the IPO: Part Two | p. 254 |

| Media Madness | p. 267 |

| Taking Back TheStreet.com | p. 277 |

| Repositioning Cramer Berkowitz | p. 283 |

| Getting Out | p. 302 |

| Confessions of an Ex-Street Addict | p. 316 |

| Index | p. 320 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

October 8, judging from the closing levels of the major averages, seemed like a pretty unspectacular day. The Dow Jones Average shed 9 points, around .1 percent to close at 7731.91. The Nazzdogs took it a little worse, losing 3 percent, or 43 points. Thirty-year bonds dropped about a point and a half, bringing their yields to 5 percent on the nose. The dollar got clocked, giving up a big chunk of that year's gains.

But these numbers masked the most important day of the last decade of investing, because on October 8, the bear market of 1998, the vicious, gut-wrenching, horrid decline that had taken stocks well past their two- and three-year lows, and brought some averages down to as low as 40 percent off their highs, came to an end. On October 8, a dreary, chilly rainy Thursday in New York, a day so out-of-kilter that even the Dow Jones Averages didn't trade at the opening (that was the day that Travelers switched into Citigroup, causing a confusing delay that kept people in the dark about the true prices of the averages until a half hour into trading), the stock market bottomed.

At eighteen minutes after 12:00 P.M.

I ought to know. I caused it. At 12:18 P.M. I capitulated. I couldn't take it anymore. I gave up both literally, at my fund, and virtually, on my Web site,TheStreet.com,where I penned a piece entitled "Get Out Now." And the prop wash from that article marked the low point in the most vicious bear market of the last century.

I didn't set out to capitulate that day. My spirits had been buoyed by the return of my wife to my trading desk after an absence of four years, and she had generated the first trading profits we had made in weeks and weeks and weeks. The day before had been our first outperformance day versus the Nasdaq in many months. I came in that Thursday thinking we were going to be cool, despite a breathtaking combination of $100 million in losses and $100 million in pending redemptions that had reduced my $325 million hedge fund that I had run successfully for a decade to a pitiful $100 million fund that was down 35 percent and in danger of going under if it didn't raise millions upon millions in cash.

I came in that day as one of the last of the bulls. I thought the market had gone down so much that it had to be near a bottom. I thought, even though we hadn't sold much of anything, we could make it, somehow, without selling and without capitulating. I thought we would be able to ride out the once-in-a-hundred-years storm that had decked so many hedge funds, and do so without having to bolt from the stock market and sell into the abyss, into the cataclysm of the market's mean, miserable maw. I came in thinking that, like Shackleton's crew inEndurance,we may not get to the South Pole, but we were going to come out unscathed and looking great and that a floor on the market was truly at hand. It had to bottom. It just had to.

I was wrong. By a minute. And by a mile. This is the story of how that bottom got formed over my own panic and my own personal crescendo of pain.

The day didn't start out ugly; the ugliness from the day before never ended. When I arrived at a quarter to four in the morning, booted up my Bloomberg and my ILX and hit my European trading wires, I saw that the bottom had fallen out of the Nikkei, as the Japanese benchmark lost 799.55 points, or 5.8 percent, wiping out a promising 6 percent gain from the night before. For weeks on end our market had been gyrating lower, but the possibility that Japan, long mired in recession, might be finally getting its house in order offered hope to some funds looking to that nation to help end the international financial crisis that had started more than a year before in tiny Thailand and had since engulfed all of Asia, Latin America, Russia, and with Long-Term Capital's demise, this country too. I had begun to put money in Japan. A small position in Mitsubishi Bank of Tokyo I had put in late last month to play the world's best acting bourse was now even smaller as of last night. I didn't even bother to get a closing quote. I knew it would be down substantially. Sayonara capital! The Japanese market was never to recover from the decline and still hovers lower than that sell-off today. If the world's other bourses were going to bail me out that day -- something I desperately needed -- it wasn't going to start in Japan.

Germany had given up 4.5 percent overnight, erasing the remnants of its once monumental gains for the year. I had been looking to Germany as another source of a turnaround. Nope, not today.

But the true slap in the face came from Britain, where the Footsie -- the FTSE -- plunged 196 points, or 4.1 percent, crashing through the seemingly impregnable 5,000 barrier, despite a rate cut by the Bank of England that very morning. Too little, too late, the market said. I had told my wife that I thought the British might cut rates, that the worries we had were spilling over there. Britain had been one of the remaining pillars in why I wanted to stay bullish. Rate cuts mean everything to me. When they happen, I want to buy, not sell, and I told her that when she came in at 8:30 she would most likely be greeted with a rally caused by the U.K. cut. We had gotten the interest rate reduction, and all that happened was an acceleration of sales overseas. That wasn't part of the plan.

The moment my machines glowed on after boot-up, on that drizzling depressing morning, the S&P 500 futures told the full story: down 24 points, a huge discount to where they were the night before. That's "down limit," a term borrowed from the commodity markets indicating that things had fallen as far as they could legally go at that moment until the index itself that the future was based on began trading. It was the most I had ever seen, a crevasse that made you tremble as you peered for a bottom. And that wasn't the worst of it. The dollar, the strongest currency in the world the week before, had started skidding suddenly with value vaporizing as if it had tripped an invisible claymore mine. Until the decline in the buck, bonds had marched seemingly inexorably toward 4 percent. Now they had whiplashed traders and were headed back full throttle to the 5 percent benchmark. As someone conditioned by sixteen years of trading that any declines in bonds and currencies were bad news for stocks, this reversal seemed outright lethal for our portfolio. Dollar, bonds, stocks, all going the wrong way at once -- atwarpspeed! "Can't anybody here play this game?" I asked the empty trading room. I couldn't believe that in this environment we were going to have to redeem our departing partners' cash. I couldn't believe that I actually thought we would have an up day in which we could do our selling in tranquility, and not chaos.

The contrarian in me might have wanted to make a judgment that things were finally so ugly that you had to step up to the plate and start buying, that the market would open so low that prices would finally reach some sort of equilibrium. But just about anybody with a cast iron constitution would be shattered early on by what brokers were saying around the Street. And, after the beating I had taken, I had a more nervous stomach than just about anybody in the game that morning. I had steeled myself for days on end about why all the bears would be wrong and why this market had to bounce. I had written endlessly that we were on the verge of a bottom and those who got out now would be known as quitters, fools, and phonies when the market roared back. I was polishing the bull's horns daily. Yet when faced with bright red stimuli this gray morning, I felt myself wavering and for once I couldn't stop the feeling. Not with that redemption deadline beckoning.

As my traders and assistants filed in I learned one piece of bad news about the market after another. First, Prudential, the giant brokerage, pronounced the market inherently unstable and ready to go much much lower. Ralph Acampora, the firm's chief technician, had cemented his reputation as an astute market caller earlier that summer when he pronounced the bull dead, expecting the stock market to decline some 2,000 points. Now we were at his price target. I got all excited for a moment when Sal asked me if I wanted to hear Ralph's new comments. I figured this could be it, the first man willing to stand up to the selling onslaught. His hands were clean. He could say that the market had reached his downside target and was ready to roar right back. I half expected him to do so. It would have been a master stroke. And it might bail me out of my redemption deadline without much bloodshed.

Nope, nothing came easy that year. In the heat of battle price targets have a way of getting adjusted, and this morning, looking at the futures and the action overseas, it was time for Acampora to take that target down. Once a raging bull, Acampora was this very morning trying to stake out a role as Giant Smokey in the brutal bear market of '98. He announced to his sales force that his Dow target, which had been 7,000, was now going to be 6,735. Those, like me, who thought that we would now bounce from Acampora's floor, saw the floor pulled out from underneath us. And this from someone with high-stakes credibility forged during years of bullishness ahead of this sell-off. The futures would have sagged visibly after such a call, if they hadn't fallen as far as they could legally go before he made his call. Who knew where the real market was.

Goldman Sachs's Abby Joseph Cohen spoke too. As if I hadn't learned my lesson yet, when Rich, my Goldman broker, buzzed me to say that Abby was coming on the squawk box (the P.A.) at Goldman, my heart paced rapidly and a grin broke through my indelible frown. Ah-hah, I said to Jeff, whom I had barely acknowledged that morning because he too had believed my thesis that we could be in for some lift, "Abby's going to put a stop to this decline right now, stop it in its tracks."

What a clown you can look like in this business, within seconds! My smile turned to anger and I mashed my phone into the side of my personal computer when Rich said, "It's not good, Jim."

Cohen had stayed bullish throughout the painful summer, not wavering for an instant from her Supertanker America thesis that our nation would pull the rest of the world through this financial crisis. Every time she spoke, she turned around the futures, or broke the nasty selling waves, as she explained why panicking was wrong and we were in a rip-roaring bull market. She was my bullish soul-mate, someone who made me feel comfortable holding onto the horns while others fled for the Kodiak dens. Unlike Acampora, Cohen is no technician. Her work is based on the future earnings power of the market as a whole. As long as she stuck by her theory that corporate profits would be bountiful, she would stay bullish.

On this particular morning, when I was in need of Abby's most bullish of Supertanker America calls, she made an adjustment to her corporate earnings view. An adjustmentdown.She took her S&P projections for the following year down a tad, just enough to cause another landslide. In a market that had come to see this frumpy curly-haired nerd as a double-hulled supertanker herself, this change jolted those whom Cohen had steered through choppy waters before. It seemed like a warning that the biggest ship of all, the U.S. market, was just as vulnerable to the financial storm as any leaky rowboat. No supertanker, just a Cunard liner headed for an iceberg.

Cries of "Cohen's getting off" echoed through trading desks worldwide. No matter that she didn't predict a decline in equities, just a decline in earnings, the move seemed like a prelude to the most important bull-to-bear switch this market had seen since once perma-bull Elaine Garzarelli yelled crash from her Lehman perch on the eve of 1987's one-day decline of 508 points. You had to get in ahead of a guru switch, not after it. While the futures couldn't trade lower, I heard brokers tell me that they had merchandise for sale off Cohen's call that was 5 and 6 points below where stocks traded before last night's bell. In another frame of mind I would have noticed that you get that kind of capitulation only at important moments in stock history. This time I just cursed myself that I would soon have to join the sellers because we had to wire out $106 million to my departing partners. I was formulating a way to capitulate with dignity, something that is akin to trying to arrange the egg on your face so it looks less scrambled and more sunny-side-up.

If anyone didn't yet recognize the sinking fortunes of financial companies, Citigroup picked this day to announce a staggering loss, even worse than had been anticipated during a previous intraquarter profit warning. The newly created institution fessed up that it had a Long-Term Capital-like global arbitrage unit that had racked up $300 million in losses previously known to the top brass. The Street buzzed that the isolated collapse of Long-Term Capital must not have been as isolated as we thought. Who else had to take a charge? If Sandy Weill took a charge, someone else had to be hurting, hurting far more than Sandy. He's good! Who else had to fess up about this leveraged lunacy? We had been battling with the financials for months on end. Fortunately my wife had us short Citigroup just the day before, as a hedge to all the other banks and savings and loans we owned. Unfortunately, it was only 50,000 shares short. Not much protection there when you are long about 15 million shares of less-well-run financial concerns.

Those looking for hope from the tech sector, which, until this day, had been holding up somewhat better than the rest of the market -- save Cisco, which was still reeling from that Cowen downgrade two days before -- had their hopes crushed right up front too.The Washington Postreported that morning that the Justice Department had more ambitious goals than just to rein in Microsoft's Internet plans. The stock of Mr. Softee, which had stayed strong throughout this period of turmoil, was indicated down 2 or 3 points at the get-go. We had owned 100,000 Microsoft going into that morning as well as 750 Microsoft calls. Supertanker Microsoft. It was our largest nonfinancial position. We looked to be in the hole for 500 Gs for that one position alone. It was offered down 6 points on the article. You could buy millions of shares there. And there were no takers.

Those who had been playing the Net couldn't even count on a rally, as Yahoo!, which at that time was known only as a search engine company, had just beaten the earnings estimates by a whopping 6 cents the night before. This was the first pure Net company to turn a real profit. It was amazing to this Netizen, a blow-away achievement. I figured a profitable Yahoo! could withstand any selling onslaught. Nah, it was looking down a dozen points! It hovered at close to $100 a share. It had been at $125 at one point the day before. The judgment of the Street spoke loudly: upside surprises don't matter when you are faced with thermonuclear meltdown.

Need more negative input? Merrill chose this day to downgrade the airlines, despite a 40 percent decline from the top already this year, based on worries of an economic slowdown. This group, under pressure for weeks, looked set to roll over again. The cell phone stocks, another set of darlings for this entire bull market since 1990, got axed from Merrill's recommendation list that morning as well. It downgraded both Ericsson and Nokia, and the latter was already down 8 in Finland. Merrill said Nokia, the bellwether for the industry, had slowing sales. Huh? I made the Merrill broker put the phone to the speaker. I couldn't believe what I was hearing. I loved these stocks. These companies were doing fantastically right now. Where did this analyst get this info?

We dodged the airline bullet, but the Nokia downgrade caught us like a dumdum right in the temple. We owned 59,000 Nokia. "Why do we own Nokia?" Jeff asked before he even said hello when he staggered in at 5:45 A.M.

"We owned Nokia," I said, "because as of yesterday sales are smoking. We just got that update."

Jeff glowered. "Merrill says they aren't."

I said, "That's news to me."

Jeff, increasingly frustrated by any attempts we made to make money on the long side, said, "So what, Merrill says they're not." I wanted to buy. Jeff reminded me that at 1:00 P.M. that afternoon we would have to send out a huge chunk of our fund and it wasn't the right time to buy. No buying allowed.

As each broker came in the news got worse and worse. J. P. Morgan, out of nowhere, suddenly came out with a call that because of the credit crunch we were going to go into a mild recession in 1999. Until that morning people had been expecting a robust economy next year. Now we're talking about a recession. "They have to talk about a recession today?" I asked Jeff.

"No time like the present," he deadpanned.

For years, ever since Bill Clinton had brought my old boss Bob Rubin to Washington, we looked to the nation's capital for good news for the economy. On October 8, though, for only the third time in history, the House of Representatives was set to vote on impeachment hearings and the Democrats, sensing that things had gone badly awry, seemed resigned to go along with Republicans' call for a full-blown proceeding. Throughout the morning there would be speeches from politicians from both parties pointing out that no man was beyond the law, not even the president. All morning, any time the market looked like it wanted to rally, a Republican would come on the tube and talk about grave times for the republic.

It was into this cauldron of gloom that my wife bounded in, about 8:30, brandishing some Martha by Mail catalogues, a couple of pieces of fresh fruit, and a completely unnecessary, I thought, in my paranoid fashion, mocking smile. "Hey, chum, looking glum," she said to me. I told her that the world looked like it had caved in overnight and we were already losing millions.

She shrugged. "So what? We'll figure it out." I thought, given the futures, the downgrades, the lack of help from Washington, that seemed pretty glib. She didn't care. She settled in at my seat while I grabbed a Diet Coke. I would be standing around today, I thought to myself. On the day when I can't take it anymore, they take away my chair too. The gods really had it in for me.

Karen asked how Yahoo! was quoted. I told her it was down 12. "Yippee, we have puts!" she said.

But, I said, "The puts are struck at 50, the stock's still up at 100." My wife hated to be corrected, especially in front of the four people who had been brought in to replace her when she retired.

"Who would have been stupid enough to bet that the stock would go down to 50?" I wanted to tell her that we put the position on when Yahoo! was at 60 and it had just run away from us. I didn't want to start the day with discord, though, and just acknowledged that I had been an idiot when I did it. She rolled her eyes, shorthand for "You are a knucklehead and I can't believe I married someone this stupid."

We met as soon as she was ready and mapped a game plan in Jeff's office, with Karen reading down the portfolio just like the old days. I knew we had to do some selling, but Karen, much more cavalier about the Fed margin rules, said that we had to wait until we saw the real whites of this market's -- and our -- eyes and we shouldn't sell anything until the last second that we had to.

"The market is set to open down huge and we have to buy," she said.

"But how about all of this bad news?" I said, as we went over the morning brokerage calls.

"They can't be right," she said. "You suddenly trust Ralph I-Can-Make-You-Poorer? How about yourself? What's the oscillator?"

When she was a trader my wife had been addicted to the Standard & Poor's oscillator, a measurement of selling versus buying. Whenever there was too much selling, she always liked to take the other side. When I told her that the oscillator was as negative as it had been since the crash of '87, she said, "We blew that one, not committing enough money. This time we can't make that mistake. That's my view."

I reminded her that we were fairly fully invested and would be overinvested at 1:00 P.M. when the money came out. She seemed completely untroubled. "How about this America Online," she said, as she took over my turret. "Max says it's looking down 8. I want to buy it for a trade."

I told her to be my guest and she bolted from the confab to get levels for trades, leaving Jeff and me dumbfounded with her sunny reading of the dire situation. We were astonished at her optimism. We couldn't bring her down despite every attempt we made to tell her how bad things were for us. She wouldn't hear it.

By the time all the Dow stocks were open, at roughly 9:50, the market was already down 100 points, including the new combined lower price for Citi and Travelers. This time, however, the coloration of the decline was distinctly different from that of the other horrible days for the bulls. Each day the selling had been concentrated in the financials, industrials, and techs. This time, though, they were whacking the drug stocks, previously an oasis. We owned a ton of Pfizer and Schering-Plough but were short 210,000 Lilly against it. Karen wanted to cover every share of Lilly at the opening and buy more Fizzy and Plug, as they were called. I reminded her that if the market kept breaking down, we would be wildly exposed to the decline. I made it clear that we didn't share her robust view of the action.

Techs, drugs, you name it, they were being hammered throughout the morning. Sometimes, when the market opens this horribly, there is a pause, related to the trading curbs put in after the 1987 crash, designed to let traders catch their breath and hunt for bargains in the newly created ruins. Not this day. The market not only continued to plummet after opening down 100, but it seemed to lose 25 points every fifteen minutes. "Ug-uly," my wife pronounced, even though Jeff and I had learned many weeks before how hideous this market could be. She seemed to enjoy the pronouncement and the angst that it spawned in her husband and his partner.

Decliners outpaced advancers by an overwhelming nine-to-one margin, virtually an unheard of ratio. Five points came right out of General Electric despite its reporting a beautiful quarter. On word of an antitrust investigation by the Justice Department, the credit card companies were all opening staggered, some down 12 to 15 points. Our few stabs at buying stocks were instantly met with reports, meaning we had bought the stocks for about a half pointlowerthan we were even trying to buy them. People were getting out so fast that they were willing to sell stocks below where buyers would pay for them! Every half hour brought progressively lower prices, more and more put buying, and fewer and fewer buyers. The eerie decline embraced all sectors. Right before noon the Dow had declined 200 points, true bear market territory, and it showed no break in the decline despite the trading curbs. Sliced through them like putty. Any stock that lifted its head got it hacked off. Everything was attracting sellers. Karen seemed even more oblivious to the conflagration as the flames leaped from screen to screen. She bought 30,000 America Online at $85, down $5. When she got the report, the stock was at $82, down $8! She just bought another 25,000. She didn't bother to ask; she said she had no time, stocks were falling too quickly.

She wanted to buy Gap and Lilly and Seagate and Ford. "They are all coming in, it is terrific, we have to buy them when we can, not when we have to. You know that's what we were taught. We can't ignore it now."

I was dying. Here we were supposed to be selling, and she was committing even more capital. "These are once-in-a-lifetime buys," she kept saying.

Did she know something I didn't? I thought. Well, at least we are going down in some serious flaming, and not with a whimper. For months I had been arguing that this market had to bottom somewhere, but these declines, this news, these pressures, the dollar crash, the Japan reversal, Germany, no rally in Britain, the drug stocks rolling over, Abby Jo going negative, Acampora giving up, the impeachment, the goddamned redemptions, no help from the Fed, it was all unraveling right before my eyes. And here's my wife wanting to buy, acting as if nothing's going wrong, acting as if it is just another day and there are bargains everywhere.

I took Jeff aside and apologized that we didn't sell sooner, apologized for being too bullish, too long, and too hopeful. The contrast between my wife, buying them on the way down, committing even more of the precious capital we didn't have, and my own belief that our franchise, the whole thing we worked for, was about to go up in smoke, was getting to be too much for me. I could barely hear myself talk over the pounding of my heart and the pain in my throat and head. Pounding, pounding, pounding that this market is finished, that we are buying into a market that is about to crash, instead of selling and selling furiously like everyone else. We are about to be obliterated, vaporized by a market that is not stopping down 260 points and isn't going to stop until it is down a thousand points. Maybe today. There were no buyers anywhere. Except in our shop! And we had no money and some crazy woman doing unauthorized trades who also happened to be my wife.

And still she bought. And still she sat there and placed orders to buy stocks down 7, 9 points. Schwab, 50,000. Mellon, 50,000. Hewlett-Packard, 85,000. Again with glee in her voice as she announced that they are just giving them away. What is she seeing? I wondered to myself. It is a holocaust out there, everyone giving up, everyone throwing in the towel, and she is buying 35,000 Household down 4 and 10,000 General Electric down every half point. "At this pace you will own more General Electric than Jack Welch," I joked to her after she put in her scale of 10,000 every half down to 60, with the stock trading at 70.5, down 4.5.

"I hope so," she said. "These are going to be great buys, especially these ones below 70. We will look back and marvel at how cheap this stock got." All I could think about was, What were we going to pay the brokers with? How were we going to buy all that General Electric and not go belly-up? How could I ever explain this one?

I wish I could say her optimism was infectious. It was more like an infectious disease invading my sanctum of fear that grew stronger by the hour, as the averages took out the year lows and the Nazz threatened to be down more than 100 points. Only the curbs were keeping stocks from falling through the floor, and we kept buying and buying and buying as if Macy's were having a one-day sale.

At noon, after another episode of furious buying when the Dow had dropped more than 270 points, I had had enough. "Let's get off the desk," I said. "We have to talk."

Karen rolled her eyes again. She had been placing orders with Land's End for a couple of kids PJs as she waited to see if we would drop 300 points, her next level where she wanted to buy. She was taking a little break. "Talk about what?" she wanted to know. "This market's on the verge of doing something big, we have to get ready."

"Ah, now that's a true statement," I said under my breath. As I gathered us into Jeff's office, she couldn't resist pointing out some bargain she saw on the CNBC ticker in Jeff's office. "Look at that. Time Warner down 6." She wondered how she missed that. "Dell, down 7, now down 8, 9!" She wanted to get right back out and buy some Dell as soon as the meeting was finished. "Jeff, what's the matter with Dell? Ooh, baby, it is really coming in. Shouldn't we be buying some of that sick puppy?"

Undaunted by her enthusiasm, I asked Jeff to give us his outlook. Jeff's all fundamentals, and he said that business had clearly slowed because of the declines in the stock market. The spillover from the financial markets, he said, was causing a decline in spending, and earnings estimates for everything from airlines to computers might be too high. Credit card sales were coming down. Information technology spending was dropping.

I listened to Jeff while I kept an eye on the ticker and an ear on what midday anchor Bill Griffeth was saying. "Two staunch bulls growing bearish." "Horrifying losses." "Panic selling." Then a story on staggering losses in mutual funds, and then a story on Clinton's impeachment, and back to a story on bloodshed on the floor of the Exchange, and credit card losses. Recession in 1999, and yet no Greenspan to bail us out.

At that very moment with the Dow down 211, and the Nazzdog composite index off 91, CNBC did a break-in: Greg Smith, the Prudential strategist, was lowering his stock allocation from 60 percent to 55 percent.

"That's it," I said, throwing my hands over my head. "Smith runs big money. All those Pru brokers will now call their clients and tell them to sell stocks. I just don't know if I can take it anymore. We are way too bullish. We have to get out."

My wife looked at me as though I were from another planet.

"Is there any chance Greenspan bails us out, because this market is so oversold it could turn around?" She emphasized that while she had been away, this was the most extreme selling she had ever seen.

I said it reminded me of the selling before the 1987 crash, when she told me we had to get out. Remember: the sell call Karen gave me that had put me in cash for that crash and saved my firm.

She said she couldn't disagree more. This action, right now, was like the crash, she said. "The crash is happening out there, right here, open your eyes. The tick's at 1,700," she said, pointing out a measure that showed an extreme level of selling historically. "Only 300 stocks are up and 2,700 are down. That's an extreme. That's the definition of what you want to see at the bottom. This is the crash," she yelled, no longer trying to buck me up, just trying to stop the brewing catastrophe. "You have to buy the crash. You didn't buy it in 1987; you have to buy it now." I thought back to how right she had been then. But she had been away now for so long, taking care of two kids, taking them to school, class mom, for heaven's sake. Hasn't read theJournalin months. Doesn't know what's going on. Her instincts, though, her impeccable instincts. I don't know. I don't know. I am so confused, so scared. The redemptions. The selling. The pressure, the pressure. I wish someone would take away the pressure. How do I get my head to stop pounding. How does she know what she's doing. How will I explain how I listened to her when we are down 1,000 points at the end of the day?

She repeated that Greenspan had to be watching this action and had to be considering another interest rate cut. In the background, on the tube, a then CNBC reporter Alan Chernoff was saying from the floor of the Exchange, "Every single component in negative territory, the transports off 158 points...serious damage...a billion-share day...an accelerating sell-off, we are having panic selling once again." The Dow had dropped another 22 points in the few minutes that we had gotten off the desk. It was fifteen minutes past noon.

"Kar, every second counts, this decline is killing us. And all of the new stuff we put on, I mean."

"Give me this," she interrupted. "If Greenspan were to move, or if you thought he was going to move aggressively, would you be buying?"

I said, "Of course. The only weakness is in the financial markets, not in the real economy. But he said on Tuesday there was no crisis." We only had an hour before we had to sell stocks to meet our redemptions. We had waited weeks now, not selling, and now we owned way too much stock, way too much, and all we had done was buy!

"Everything tells me we should be buying, everything," she repeated, exasperated. Now the Dow dropped another 20 points before my eyes, no doubt from the Pru-related selling. I saw GE at 70 on the ticker. We had probably just bought more with my wife's silly scale.

"No, no no," I said, throwing down my legal pad and pounding the marble coffee table in Jeff's office. "We have to get out, we have to get out now," my voice shaking, sick, sick that we had to give up after being bullish all the way down, all the way down for 1,000 points. "That's it," I said, "I can't take it anymore. We are selling, I am undoing your buys and getting us out of this. This market is going to %&#! and it's going there #%$&."

The Dow was down 262 points, the Nasdaq had opened down 103.

I stormed out of the meeting, took my place back at my desk, shoved the catalogues away, and began to sell the stock that my wife had put on. I canceled the GE scale, dumped 5,000 shares of ten stocks, and told my brokers to wait two more minutes and repeat it again and again and again until we had sold everything we had bought and then some. I asked my traders to see where I could sell a million shares of BayView, and 500,000 shares of a couple of other savings and loans. I had been beaten.

And I beat out a piece, a little piece, but the most important piece I had yet to write forTheStreet.com,saying that it was time to get out, that the crash was at hand. Big losses awaited us. The piece reiterated my arguments that I had just delivered in Jeff's office, without any of my wife's caveats. As I sent it I looked up and saw some commercial with Peter Lynch and Lily Tomlin talking about how "buying what is hot without research is not investing, it is gambling." Now they tell me, I thought to myself. It was 12:29 P.M.

After the commercial ended, Bill Griffeth came back on and said that Ron Insana, the CNBC evening anchor, had a story about Lyle Gramley, a former Fed official, telling a Schwab client group about a possible rare between-meetings conference call by Greenspan. I saw the market lift 20 points, a visible lift. Maybe a Fed bailout? I thought to myself. Impossible. Not after what Greenspan said earlier in the week. Not after what I just said. Not after the story I had just sent toTheStreet.com.

At 12:34 P.M. a rarely smiling Ron Insana -- there had been nothing good to smile about for months -- came on and said that there was a possibility that the Fed was going to act "relatively swiftly" because the "wealth destruction was so noticeable." He then repeated it, that the Fed would not be waiting until its November 19 meeting, that the Fed knew the markets were being hammered and it would provide the liquidity necessary to stop any decline. He said this would be extraordinary but he had been working the phones all morning and he believed it. As everyone in the office regarded Ron as a bear, his credentials punctuated the report with veracity.

Suddenly the Dow rocketed from its low, clawing back first 30 and then 40 and then 50 points as Ron talked about the teleconference easing, "maybe by as much as a half point." A half point! That would be huge. That would be unprecedented. That would change everything. Now the Dow was down less than 200. Twelve-thirty-eight P.M. And the Nazz was ramping up, down only 100, and then under 90. It was at that moment that my story appeared telling readers to get out. My wife was listening to the TV as intently as I was. She looked at my computer screen and expressed horror when the "get out" story popped up onTheStreet.comat the same time that Ron Insana was breaking the news that would cause the bottom not to get lower. "Where are the caveats?" she asked. "Where is the stuff about how the market will rally if the Fed eases?" I shrugged. I had left them out. I hadn't wanted to seem wishy-washy. When I wrote the piece I thought the world had ended. Had I gone for a soft pretzel or for an Italian ice, or if I had just gone out for air, or a trip to the men's room, I wouldn't even have written the story. And why does it have me say "get out"? Karen asked. I didn't say get out. I wanted to get in, she said. What if Insana is right? "You will never live this piece down," Karen was screaming at me. "I hate this stupidStreet.com.It ruins your ability to be flexible. Ruins it."

What have I done? I thought. Forever I have that image of Alec Guinness falling on the detonator to blow up the bridge over the River Kwai. My bullish bridge blown up right when it was about to take me where I had to go. What had I done?

"I blew it," I said quietly to her as she stood over my shoulders. Then enraged, I shouted, "I blew it." I said it ten times. Giants win the pennant, like. "Iblew it!"

"No, you didn't," my wife said calmly. "You didn't. You didn't blow anything. Cancel the sell orders. The market is done going down."

But the readers, I said, will forever think that I am an idiot. I can't change my view like that.

"You aren't a guru," she said. "You are a guy, a big fallible guy and you blew it, but you know it. We missed 50 points on the Dow that's all. Sure you blew it. Everybody blows it. Just admit you made a mistake and change. You aren't a guru," she repeated.

It was too late, I said, a correction to the piece won't appear for another half hour.

"Forget the piece. Save the fund. Pull all the sell orders," she said. "Just listen to me. We are done going down. Maybe for good."

"But how about the margin, the money? We only have a few minutes left to make the wires. If we don't sell anything we will be borrowing too much money overnight," I said. "We'll get in real trouble with Goldman." Did Karen not know the margin rules?

She looked at me for a second the way a mother might a child that feared getting yelled at by the principal for doing something that everyone gets away with. "Didn't you always want to be fully margined, 200 percent long at the bottom? Didn't you always want to have a Fed margin call at the bottom? That's what you will have and you will be proud of it. It'll be a badge of honor. This is your chance to do what you should have done after the '87 crash. Just let it ride. Let it ride." She added, noting that with the day's huge volume and confusion, it would probably take Goldman weeks to figure out how much we really had to margin. You could borrow against those savings and loans if they were going up, she said. And they will go up with this Fed news. By that time we'd be well on our way to making it back to the black and it wouldn't matter. "Anyway," she said, "we used to run it up all the time at Steinhardt, borrow way more than we should have. They'll let you go if you do the commish and say you won't do it again."

I wanted to know about the banks and savings and loans. shouldn't we be selling them now that there were bids developing because of the emergency easing coming? Shouldn't we be taking a chance and selling into this momentary lift?

"You want to be just where you are, with all of these crummy little savings and loans," she said, ticking off the names from her position sheets. "They'll rally with every Fed ease that you didn't expect. You will sell the BayView at $20 instead of the eight bucks you might have gotten a few minutes ago." She then gave me her targets on where the rest of the banks and savings and loans would go to. "Don't you sell a thing. You already didn't listen to me once today, don't do it again."

I could see that she was getting ready to bolt to go home, probably trying to make it home before our eldest got back from first grade. It was only a little after 1:00 P.M. A half day's trading was ahead and who was to say that this rally that began minutes after I gave up could last?

"How can you be sure it is the bottom?" I said, trying to divine what she saw as I stood watching the markets rise on the eight screens in front of us at the top of the trading desk. "What makes you so certain? How do you know this bottom will hold? How can you go now? How do you know you will be right?"

"Simple." She bent down and whispered to me so that others in the room could not hear: "Because at the bottom even the coolest, most hard-bitten pros blink. At the bottom the last bulls throw in the towel. At the bottom, there is the final capitulation." She waited until it dawned on me who she was talking about. "At the bottom, Jimmy, you capitulated. At the bottom you gave up. That's how I know it's the bottom. It's okay. Michael Steinhardt" -- her old boss -- "capitulated at the bottom in '87. It happens to the best."

In the last thirty minutes since Insana spoke one stock after another had indeed bottomed, Microsoft, down 6, Cisco down 3, IBM down 4, Seagate down 4, Dell down 9, Intel down 4, all were headed to the black. The brokers were screaming. The financials were all up fractions, on their way to multipoint gains. The world had changed from red to green on that Fed intervention call. Owners of puts, who had been coining money on the downside, now wanted bids. They wanted to cover the shorts that had made them gazillions in the last six weeks. There were no offerings to be had. None at all. The selling was done, my trader yelled out. "There's nothing but buyers." The tape left not even a small hole of doubt; it was off to the races. Almost straight up for the rest of the hour. Short sellers at last were panicking. Even for the stocks that we needed to sell there were suddenly no offerings. The shorts had disappeared, like vampires waking to broad daylight.

"Should we be buying?" I said, now totally bewildered. She reminded me we bought all the way down, when the prices were much better. Would there be a pullback?

"There won't be one of any significance," she said. "We can't do anything anyway." True, we were borrowed to the max. More than to the max.

"Do you think it will ever pull back? Maybe in a couple of days? Weeks?" She didn't bother to answer, just kept packing up, tossing out a Lands' End catalogue she had ordered from during the height of the downturn and retrieving the Martha by Mails that I had shoved aside when I had panicked and started selling into the maelstrom.

She was leaving some written instructions of when to take off the positions she had bought all morning, positions that would be worth millions of dollars more than she had paid for them in a matter of an hour or two. America Online, Gap, Seagate, and the questioned General Electric. Now all much better to buy. Now not even looking back. "A pullback?" she asked rhetorically. "No. Not likely. Not after this selling crescendo." She jammed some catalogues into her Coach bag, stood up, tidied up my desk space one more time, scrawled on a little Post-it that she covered with her hand, and headed for the exit.

And with that she said goodbye to everybody, just a simple wave. Not even a see-you-later. Hasn't been back since. Never will be. No encores for Karen.

The market rallied from then on for the rest of the year in one of the greatest comebacks in history, one that never faltered. We made back $120 million almost in a straight line, getting off margin about a month later and breaking into the black a month after that. We sold the BayView at $20 and dumped the rest of the savings and loans at much higher prices after the Fed eased and eased some more, causing a mad bull market in the very financials we were hung up on. The market rose until Nasdaq hit 5,000 and Dow 12,000 from their bottom at 12:18 when I pushed aside those catalogues and got to work trying to undo my wife's bullishness with my own bull-turned-bear imitation.

We finished up for the year, still disappointing relative to the averages, which we never caught, but much better than the intraday down 38 percent level that we hit on October 8, the day we should have gone bust. We waived a couple of million dollars in management fees because we didn't make more than a couple of percent and weren't proud of what we did, even though we were proud that we turned the ship around. The crisis occurred early enough in the month that no one other than the minute-to-minute folks even knew it had occurred. If you stayed in the fund you increased your worth by more than 200 percent from that bottom in the next two years. Sweet. Many of the departing partners tried to come back in after we finished up 60 percent the next year, but we didn't let them. Even sweeter. But the pain of those dark days was not exorcised by the pleasure of seeing the fund back in the black and healthy again. Goldman never did figure out that we borrowed some $30 million more than we should have, given the flimsy nature of the collateral, and we were more than fully margined at the bottom, just as you want to be, just as every great hedge fund manager wishes he were. The readers ofTheStreet.com,however, never forgave me for panicking out, even as I switched direction in my writings a day later. According to Karen, it was a sign of strength, not weakness, that I could capitulate and then embrace the long side again so fast. The worst thing to do is to cling to a losing position even for a minute when you know the facts have changed and you are wrong. Flexibility is what distinguishes a good trader from a bad one. But the readers just remembered me as the man who capitulated at the bottom, who defined the bottom.

Oh yeah, and that Post-it my wife slammed to the side of my machine as she left to go greet our daughter after her day at school? "It's good to be good, but it's better to be lucky."

If only it really were luck, then I would at least have a chance of duplicating the last trading performance of the woman they still call the Trading Goddess.

Copyright © 2002 by J. J. Cramer & Co.

Excerpted from Confessions of a Street Addict by James J. Cramer

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.