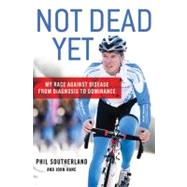

PHIL SOUTHERLAND is the founder of Team Type 1, a team of championship bike racers. He and Team Type 1 have been profiled in numerous cycling and diabetes publications, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and the Atlanta Journal Constitution. He lives in Atlanta, where Team Type 1 is based. Visit him online at www.teamtype1.org.

JOHN HANC teaches writing and journalism at the New York Institute of Technology. He is a long time contributor to Newsday and a contributing editor to Runner’s World magazine, as well as the author of The Coolest Race on Earth. He lives with his wife and son in Farmingdale, New York.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.