What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

INTRODUCTION

In the 1990s Chrysler executives used to joke that they could tell a Jeep driver from a minivan driver just by looking at his or her watch. Timex watches were for practical people, those utterly unconcerned about putting up appearances and thus unworried about driving a mommy-mobile. Even if they were mommies.

But Rolexes signaled people whose self-image couldn’t cope with a minivan and who wanted to flaunt their rugged, outdoor lifestyle. Even if ruggedness only meant hitting potholes en route to the mall in their Jeep Grand Cherokee Orvis Edition. With a skinny Venti Latte in the cup holder, of course.

For decades, the connection between cars and self-image has been understood and appreciated by prominent philosophers. Consider the Beach Boys. Their song “Fun, Fun, Fun” (1964) wasn’t so much about the Ford Thunderbird as about the free-spirited teenaged girl who drove one.

Other songs celebrated drivers whose personas defied the stereotypes of their cars. “The Little Old Lady from Pasadena” (Jan & Dean, 1964) was about a granny who flew around the freeways in a “brand new shiny red Super Stock Dodge.” In researching this book I learned about a real-life grandmother who terrorized other drivers just like the one in the song, except that she drove a Mustang. She lived in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, which probably explains why she didn’t wind up in a song. “The Little Old Lady from Oconomowoc” would have left a whole generation of Americans tongue-tied.

A handful of cars in American history, however, rose above merely defining the people who drove them. Instead, like some movies (e.g.,The Big Chill) and some books (The Catcher in the Rye,etc.), they defined large swaths of American culture, helped to shape their era, and uniquely reflected the spirit of their age. These cars, and the cultural trends that they helped define, are the subject of this book.

The underlying premise here is that modern American culture is basically a big tug-of-war. It’s a yin-versus-yang contest between the practical and the pretentious, the frugal versus the flamboyant, haute cuisine versus hot wings, uptown versus downtown, big-is-better versus small-is-beautiful, and Saturday night versus Sunday morning. The elemental conflict between these two sets of values is amply evident in the contrast between the first two cars in the book, the Ford Model T and the General Motors LaSalle. The inexpensive Model T was the pinnacle of practicality, the first people’s car.

It didn’t have much style. But during its remarkable twenty-year run, from 1908 to 1927, the Model T gave farm families unprecedented mobility and a taste of the city lights. Even if they were only the lights of Muncie.

The LaSalle, in contrast, was the first mass-market designer car, an early yuppie-mobile that was intended for getting attention as well as for getting around. It debuted in 1927, the very year that the Model T died. The two cars were perfect bookends. They’re the only pre–World War II cars in this book, because American cultural evolution hit a roadblock in the 1930s and 1940s.

Those decades, of course, were dominated by Depression and war. Production of civilian cars was suspended during World War II, and Detroit’s factories were converted to produce planes and tanks. American cultural upheaval, at least overtly, took a time-out, too. During the Thirties and Forties Americans were mostly focused on finding food and work, and on staying alive.

But twenty-five straight years of virtually nonstop Depression and war came to an end with the armistice in Korea in 1953. By then Americans were ready to let loose, which made the timing perfect for the Chevrolet Corvette, the first modern American sports car. The pivotal figure in Corvette history was a Chevrolet engineer who had been raised as a Bolshevik boy in Russia before coming to America and winding up at General Motors.

The defining design statement of postwar America’s sky’s-the-limit ethos was tail fins. Chrysler actually sold them as safety devices, and the company’s top designer was honored by the Harvard Business School (really). Chrysler almost won Detroit’s great tail fin war, but General Motors struck back in 1959 with Cadillacs that had the biggest tail fins ever.

The man who designed them, Chuck Jordan, died in late 2010, at age eighty-three. I was fortunate to have interviewed him before he passed away. Nearly half a century on, Jordan told the tale of the fins with relish.

Corvettes and tail fins were all about pretension, but an import from Germany, America’s erstwhile wartime enemy, pulled the pendulum back toward practicality. The little Volkswagen Beetle, which was the ultimate anti-Cadillac, debuted in the 1930s as Adolf Hitler’s “people’s car.” Decades later it became the unofficial car of American hippies, completing an automotive and cultural journey of epic sweep.

Volkswagen marketed the Beetle with clever, self-deprecating advertising. One ad told how a farm couple in the Ozarks, living in a log cabin, bought a Beetle to replace their dearly departed mule.

GM’s belated response to the Beetle was the practical but problematic Chevrolet Corvair, launched in late 1959, which fared less well. It inspired an unknown young lawyer named Ralph Nader to write a book calledUnsafe at Any Speed.

The Corvair’s lasting legacy has been America’s greatest growth industry: lawsuits. The car sentenced millions of Americans to watch personal-injury television commercials from law firms, unless they’re really quick with the remote control button.

Every vehicle in this book represents either practicality or pretension, although a couple of them straddle the great divide. Pickup trucks started out as down-and-dirty work tools until Detroit discovered it could make billions by selling lavish designer trucks. The seats on some of them have more leather than most cows.

For many people, especially those under thirty-five, cars aren’t nearly as important as iPads, iPods, cell phones, apps, personal computers, and BlackBerries. The modern fascination with electronic devices might make the idea of writing about the social significance of the Ford Mustang seem quaint, a relic of an era when “laptop” wasn’t a high-tech term.

But cars continue to provide unique personal freedom and mobility. They spawn powerful emotions, experiences, and memories, of family road trips, one’s first car, or one’s first sexual adventure.

Hardly anyone keeps the purchase papers for their first computer, or gives the device a name. But some Americans do both for their first cars. The Beach Boys sang a song about a drag race called “Shut Down,” but nobody has yet recorded one called “Download.”

This book reflects my fascination with cars and car culture, which grew slowly, over many decades. As a boy in 1950s Laurel, Mississippi (where our family was known as the EYE-talians), I learned about the early explorers through our cars: Hudsons and DeSotos. It took me years to realize that not all cars were station wagons.

In 1960, when I was ten, we moved to suburban Chicago and became a two-car family for the first time, just like millions of other Americans. Our station-wagon treks to visit my two grandmothers back East created a family tradition: the annual breakdown on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. I cherish the memories . . . sort of.

I wasn’t a hot-rodder in high school. In fact, I wasn’t a hot anything. But automobiles were taking on important dimensions in my adolescent psyche.

In 1964, the year that the Mustang and the Pontiac GTO debuted, I found myself in Mr. McGowan’s freshman math class at St. Francis High School in Wheaton, Illinois. I hated math, but Mr. McGowan, bless him, gave us boys an occasional break from dreary decimals and unfathomable fractions to talk about cars.

We discussed whether Pontiac or Chevy had the better lines that year (it was Pontiac, as I recall), and whether anybody’s dad had bought a Mustang V8 (yes, but not my dad). Alas, I learned to drive on Dad’s pedestrian six-cylinder Chevy Bel Air with a three-speed stick shift on the steering column, the proverbial “three on the tree.”

I didn’t buy my first car until college at the University of Illinois. It was a 1969 Chevy Nova with an anemic six-cylinder engine that made passing on the two-lane roads around Champaign a death-defying adventure. That Nova cost around $2,200, about the price of a new fender today.

The hot car in college, a ’69 Pontiac GTO, belonged to my friend Dale Sachtleben. Once we took it on a road trip out East and Dale got a speeding ticket in Delaware for going ninety miles an hour, which was his slowest speed of the entire trip.

More than thirty years later, when Pontiac launched an updated version of the long-dead GTO, I reconnected with Dale for a nostalgia-trip test-drive in the new model. He had gray hair, I was a cancer survivor, and we were both (gulp) Republicans.

We drove the new GTO to tiny Greenview, Illinois, his hometown just north of Springfield, best described as sitting at the corner of corn and soybeans. There we raced up and down the little farm road that once served as the local drag strip, and for a while we were kids again. Cars can do that.

My first job out of college was in 1973 in Decatur, Illinois, where our next-door neighbors, the Whitneys, owned a 1960 Thunderbird. By then Ford had added a backseat to the ’Bird, which had been a taut two-seater when it debuted in 1955, but the low-slung, boulevard-cruiser styling remained. The Whitneys’ son Clay, then a boy and now a business owner, still keeps the classic car today.

The first car in this book that I owned was way more pedestrian and practical: a 1984 Chrysler minivan. My wife and I were in Cleveland, where I worked for theWall Street Journal, and we had three boys under age six.

The minivan’s interior was so spacious that it seemed to have designed-in demilitarized zones that kept the kids from killing each other, and from driving us nuts on road trips. For a few years, before they became mommy-mobiles, minivans actually were cool. (No kidding.)

In 1985 my boss,Journalmanaging editor Norm Pearlstine, transferred me to Detroit. It wasn’t clear what I had done to be sentenced to Detroit after living in Cleveland, but the truth was I loved it.

I felt like an anthropologist living among exotic natives who worshipped strange gods called “Multivalve Engine,” “Zero to Sixty,” and “Pound-Feet of Torque.” Not to mention the twin deities “Intercooler” and “Supercharger,” devices that boosted the power of internal combustion engines, and thus made them worthy of worship at the automotive altar.

In Detroit I discovered the nuts and bolts, pardon the pun, of the car business, from balance sheets to balance shafts. Covering the auto industry was a journey of discovery that led to a Pulitzer Prize. Our son Charlie, then in grade school, told his teachers his dad had just won the “Pulitzer Surprise.” In my case he was about right.

In 1994 I left Detroit to become an executive with theJournal’s parent company, Dow Jones. But my fascination with the automobile industry and its culture continued, partly because I wrote occasional car reviews for one of the company’s magazines,Smart-Money.

One vehicle I tested was the Ford Excursion, launched in 2000 as the largest SUV ever. The Excursion was so big that Ford held the press preview in Montana, about the only place the vehicle would fit.

I skipped that event and, instead, drove the Excursion through the somewhat tighter confines of Greenwich Village, where I managed to parallel park it on a street. Of course the two curbside wheels climbed onto the sidewalk, but the Excursion was so obscenely heavy (about four tons) that I didn’t even feel the bump.

The Nissan Titan pickup truck, which I reviewed in late 2003, was almost equally massive. I attended that press preview, held in Napa Valley, as much for the wine as for the roads.

Around that time I started thinking about this book. Automobiles are ubiquitous. But there’s little appreciation of how certain cars have reflected the way we think and live, becoming shapers and symbols of their eras. I found the stories of the cars and of the people behind them to be full of surprising twists and turns, even though I had been writing about the auto industry for nearly twenty-five years.

The research, which I began in 2007, took me all around America. I drove Priuses in Michigan, Jeeps through Colorado, and pickup trucks around the Texas Hill Country and Midtown Manhattan, feeling right at home in the former and like an alien invader in the latter. At least the pickup I drove in New York didn’t have a Confederate flag decal or a gun rack.

I attended a slew of car conventions and shows, including the centennial celebration for the Model T Ford in Indiana in the summer of 2008. One man there had driven his Model T from “UCLA,” which he explained meant the “Upper Corner of Lower Alabama.”

His hometown there happened to be Monroeville, also the home of the reclusive Harper Lee, author ofTo Kill a Mockingbird. It was a book that, like the Model T Ford, had reshaped American life and thought.

At one car show a man displaying his AMC Gremlin told me his favorite story: about a woman who confided she had been conceived in the backseat of a Gremlin. Not a good start in life. Later comedian Jon Stewart told me his first car was a 1975 Gremlin, and that his cat peed in the backseat on the day of his high school graduation. No wonder he can laugh at anything.

The annual Bloomington Gold Corvette exhibition in Illinois and the National Corvette Museum in Kentucky provided memorable visits. The museum, complete with relics and records from the car’s history, should be called the Corvette Cathedral.

The epitome of car shows is the annual Concours d’Elegance held every August at Pebble Beach, California. There’s nothing like gathering at 6 a.m. to feel the cold mist rolling in from the ocean and watch the priceless Hispano-Suizas and Delage De Villars Roadsters—names that shouldn’t be pronounced without an affected accent—rolling onto the 18th fairway for the show. Sacred cars on sacred ground.

I also tackled the more mundane but ultimately rewarding work of delving into the depths of automotive archives. They included the Benson Ford Research Center in Dearborn, Michigan, the Collier Museum and Library in Naples, Florida, various branches of the New York Public Library, and the National Automotive History Collection at the Detroit Public Library.

My research was hitting high gear when, suddenly, I took a detour. In the fall of 2008 Detroit’s car companies careened into a crisis that resulted in the bankruptcies of two of them: General Motors and Chrysler. These were historic, albeit tragic, events, and I was pulled into writing about them.

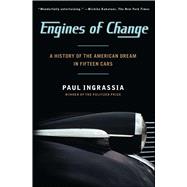

The result wasCrash Course, my 2010 book about the bailouts and bankruptcies, which was really a book about human behavior. So is, in a different sense,Engines of Change.

When I returned to this book, after my hiatus, I travelled to the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, a shrine to native son and Nobel Prize–winning author John Steinbeck, who often put cars in his books.Cannery Rowsays the Model T revolutionized sex and marriage.The Grapes of Wrathdescribes a bitter trek westward in a makeshift pickup truck. The Steinbeck Center still displays the dark-green GMC pickup that the author drove around America to write his 1962 travelogue,Travels with Charley.

The research also took me to Japan and to a less likely overseas destination: Copenhagen. There I participated in a weekend road rally with the Cadillac Club of Denmark, an organization whose very existence caught me by surprise. The club’s members cruise past medieval castles in tail-finned cars that seem almost equally medieval, even though they were “alive” during my lifetime.

My research was both a literary and an automotive journey. I rereadOn the Road, Jack Kerouac’s automotive journey of self-discovery. And two wonderful books, also from the 1950s, that lampooned the automotive excesses of the era:The Insolent ChariotsandThe Hidden Persuaders. P. J. O’Rourke’sRepublican Party Reptilecaptured the close connection between pickup trucks and beer.

This road of research also included film and television, includingThe Roy Rogers Showof my boyhood,Route 66of my adolescence, andCurb Your Enthusiasmof my, um, maturity. Automobiles played prominent roles in all three, as well as many other TV shows and movies.

In the afterword I’ll mention some cars that might have been included in this book but weren’t. My reasoning probably won’t sit well with fans of cars that didn’t make the cut, but this isn’t a book about the best cars or the worst cars. Instead it’s about the cars that helped to shape how we think and live, which is a very select group. Put another way, like a play in four acts, this is a history of modern American culture in fifteen cars.

Whether the cars shaped the culture or the culture shaped the cars is just another version of whether the chicken came before the egg, or vice versa. Let’s just say it’s both. But I will answer straightaway a question I suspect some readers will want to ask me: What kind of car do you drive?

If you really need to know . . . it’s a red one.

1

WHEN HENRY MET SALLIE: CAR WARS AND CULTURE CLASHES AT THE DAWN OF AMERICA’S AUTOMOTIVE AGE

Someone should write an erudite essay on the moral, physical, and esthetic effect of the Model T Ford on the American nation. Two generations of Americans knew more about the Ford coil than the clitoris, about the planetary system of gears than the solar system of stars.

—John Steinbeck,Cannery Row1

Just north of downtown Detroit on a small street called Piquette sits an inner-city storefront church called the Abundant Faith Cathedral. By the looks of the surrounding weed-choked lots and empty factories, abundant faith is exactly what’s needed, not to mention plenty of hope. The neighborhood is a postindustrial ghetto, although right across the street from the church is a functioning business called the General Linen & Uniform Service. It occupies the first floor of an old building where, as unlikely as it seems, modern America began.

It was here, in the early autumn of 1908, that Henry Ford started producing a car called the Model T, so named because it followed previous Ford cars called the Models N, R, and S. But the Model T was so radically different that Henry Ford had to fight to build it, even within the company that bore his name.

Instead of being built and priced for America’s emerging industrial elite like most other cars of its day, the Model T was simple, practical, and affordable. “I will build a motor car for the great multitude,” Henry Ford said. “No man making a good salary will be unable to own one—and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.”2

The key to hours of pleasure as opposed to days in the repair shop was a reliable and light design. The Model T’s chassis flexed with the road, often uncomfortably so, but it could be driven or pushed out of places from which bigger, heavier cars wouldn’t budge. Henry Ford’s favorite joke was about the farmer who wanted to be buried in his Model T, because it had gotten him out of every hole he had ever been in. The car was available in body styles ranging from a racy open-air “speedster” to a five-passenger sedan. It even could be adapted to fit campers equipped with water tanks and sleeping beds, presaging the Volkswagen Microbus half a century later.

The “Tin Lizzie,” as the Model T was nicknamed for reasons now obscure, provided unprecedented mobility, easing the isolation of farm life and ending rural peasantry in America. It initially cost $850, compared to upward of $1,000 for comparable cars, but by 1924 the Model T’s price would be just $260. The drastic price cuts were made possible by another innovation, the moving assembly line, which Ford developed after outgrowing the Piquette Street plant and moving to a larger factory a few miles away. He followed the moving assembly line with the $5 day, more than double the average factory wage at the time.

The Model T and mass production sparked a chain reaction that created a new world. To paraphrase the story of the original creation: “Yea, Henry begat the Model T which begat mass production which begat the $5 day. And verily, those begat the middle class, the suburbs, shopping malls, McDonald’s, Taco Bell, drive-through banking, and other things beloved of the modern-day philistines.” That might not have been the erudite essay Steinbeck had in mind, but it does describe what Ford wrought.

The Model T promoted social networking one hundred years before Facebook and fostered a sexual revolution a half century before the pill. “Most of the babies of the period were conceived in Model T Fords and not a few were born in them,” wrote Steinbeck. “The theory of the Anglo Saxon home became so warped that it never quite recovered.”3And it wasn’t just Anglo-Saxon homes. Eventually the Model T would be made in nineteen countries from Australia to Argentina, and many places in between.

This rich legacy caused some 13,000 Model T collectors to gather in America’s heartland in July 2008 to celebrate the centennial of the revolutionary car. “The Ford Model T has never been just a car—in many ways, it’sthecar,” a representative from the Ford Motor Company told the crowd. “The car that started it all. The car that put the world on wheels. The car that changed everything.”4Looking strikingly like his great-great-grandfather, the speaker was a twenty-eight-year-old purchasing manager named Henry Ford III.

The Model T ruled the roads for twenty years, from 1908 to 1927, until suddenly its day was done. It was hit by the meteor of the Roaring Twenties, when cars became vehicles for personal expression as well as for transportation. The automobiles that epitomized this change debuted in 1927, the Model T’s last year, as the first mass-market designer cars—“inherently smart, individual and racy,” declared a sales leaflet, “the epitome of this zestful age.”5They were LaSalles, junior versions of Cadillacs, the most prestigious marque in the General Motors hierarchy of brands.

Billed as a “companion brand” to Cadillac and sold by the same dealers, LaSalles were smaller, lighter, and sportier. They were aimed at the “smart set,” the 1920s term for “yuppies.” While the Model T was relentlessly practical, the ultimate household appliance, the LaSalle was exuberantly stylish. Harley Earl, the man who designed it, was the polar opposite of Henry Ford.

While Ford was the consummate country mouse, raised in then-rural southeast Michigan in the years following the Civil War, Earl was a sophisticated city mouse. He hailed from a well-to-do family in Los Angeles. He graduated from Hollywood High in 1912, attended Southern Cal and Stanford, and launched a career building custom car bodies. One of his clients was a silver-screen cowboy named Tom Mix, for whom Earl designed a car with a saddle on the hood. (It was, to be sure, a one-off job.)

Through an unlikely chain of connections Earl was invited to Detroit in 1926 by the bigwigs at General Motors to try his hand at design. He soon realized that Detroit, just like Hollywood, could manufacture dreams. A year later Earl was hired by GM to form the auto industry’s first design department, which he would run for the next thirty-one years, from the Jazz Age to the Space Age. “People like . . . visual entertainment,” Harley Earl would say, and that’s what he would give them.6

During its fourteen-year life the LaSalle did for upward mobility what the Model T had done for personal mobility. The two cars epitomized different philosophies about cars, society, and people. One was country, the other was country club. One was dutiful and self-reliant; the other beautiful and self-indulgent. The Model T might have been used for sex, but the LaSalle was designed for sex appeal. The yin-yang contrast between the two cars would reflect different philosophies that helped shape American culture and would echo in future cars that, like the Model T and the LaSalle, defined the ethos of their day.

In the early 1920s, the story goes, a farmwoman was asked by a social scientist why her family had a Model T Ford but not indoor plumbing. She replied: “You can’t go to town in a bathtub.”7Apocryphal or not, the story says everything about the Model T’s appeal. But Henry Ford’s road to success, like the Model T’s famously bumpy ride, was anything but smooth.

It was fortunate that Ford lived a long life, beginning during America’s Civil War and lasting until after the Second World War. He was the proverbial late bloomer, born on July 30, 1863, less than a month after the Battle of Gettysburg, in Dearborn, Michigan, then a farming community ten miles west of downtown Detroit. The oldest of six children, young Henry hated farm chores but loved to tinker with machinery. At age sixteen he left home to work in the machine shops of Detroit.

By 1893, at age thirty, Ford had become chief engineer for the city’s Edison Electric Illuminating Company, but his mind was restless. Three years later, using a design he had seen in a magazine, Ford built his first car in a shed behind his house, much like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak would build the first Apple computer in a garage some eighty years later.

Ford’s car was basically a platform steered by a rudder, powered by a two-cylinder engine, and borne on four bicycle tires. Thus it was named the Quadricycle. Ford had been so focused on the mechanics of his creation that he hadn’t noticed it was too big to fit through the door of his shed. But he was so eager to see it run that he tore through a wall with an axe and, around 4 a.m. on June 4, 1896, the first Ford car rolled onto the streets of Detroit.8After running a few blocks it stalled out, which prompted jeers from the street transients who witnessed the spectacle. But Henry Ford was jubilant that he had created a working automobile.9

Three years later Ford quit his job and found backing from local investors to start the Detroit Automobile Company. But that company went broke after less than two years. Like dozens of other early automotive entrepreneurs, Henry Ford had failed, and it wouldn’t be his last time.

He kept tinkering with cars, and in October 1901 he entered a race on a dirt track in Grosse Pointe, just east of Detroit. The race would pay a $1,000 prize to the winner, and luckily for Ford only one other car was running. The other entrant happened to be Alexander Winton, a mogul from Cleveland who owned a car company bearing his name. Henry Ford, in contrast, was a little-known Winton wannabe.

At first Winton’s car led handily but midway through the race a smoking engine forced him to slow down. Ford, meanwhile, struggled to keep his car from tipping over. But he had deployed a local mechanic to hang on the side of his car during the race to provide balance, like someone hiking out over the side of a sailboat. The tactic looked comical but it worked, allowing Ford to cruise to victory and claim the $1,000 purse.

Ford’s enhanced reputation attracted investors for another car company, the Henry Ford Company, with Henry as chief engineer and one-sixth owner. It seemed promising but just four months later the single-minded and cantankerous Ford quit in a dispute with his backers. They wanted to build luxury cars aimed at upscale buyers, while Ford wanted to focus on racing cars to capitalize on his recent success.

With Ford gone the financiers found a new chief engineer named Henry Leland and changed the company’s name to Cadillac. It would later be bought by General Motors and its brand would reign for decades as America’s premier automotive status symbol. By age thirty-eight Henry Ford had helped form two car companies and had lost them both. He vowed that his days as an employee were over, or as he put it, “never again to put myself under orders.”10

The odds against the young inventor were long, however. He was not only a two-time loser but America already had lots of car companies. There were around sixty at the time, including such long-forgotten names as Maxwell, Thomas, Holsman, White, and the Babcock Electric Carriage Company of Buffalo, which made an electric car a century ahead of its time.

Nonetheless, Ford had a third chance courtesy of local businessmen, who deployed a young bookkeeper named James Couzens to round up investors for his latest venture. Couzens had the financial and administrative aptitude that Ford lacked. In less than fifteen years the two men would revolutionize the world as much as two of their contemporaries, Lenin and Trotsky, minus all the mayhem.

The Ford Motor Company formed on June 16, 1903, and a month later sold its first car, a four-passenger Model A, to a dentist in Chicago. Within ten months Ford Motor had sold 657 more Model As, booking nearly $100,000 in profit, equivalent to about $2.4 million today. In January 1904 Ford set a new speed record of 91.37 miles an hour with a car running on the frozen ice of nearby Lake St. Clair. Less than two years after his second company had failed, Henry Ford was on a roll.

While his luck had changed, Ford’s cocksure abrasiveness hadn’t. He started squabbling with his investors over the familiar issue of what kinds of cars to develop. Most of them favored big, heavy cars such as the Ford Model K, with a price tag of upward of $2,000. But Ford’s view of the fledgling car market had evolved. He wanted to pursue the direction set by the new Ford Model N, a lighter and cheaper car launched in 1906 priced initially at only $500 and aimed at downscale buyers who couldn’t afford cars like the K. It was a classic big-car-versus-small-car conflict of the sort that would rage in the auto industry for the next hundred years.

As the argument heated, Ford and his allies squeezed their troublesome investors financially. They formed an entity called the Ford Manufacturing Company to supply components for Ford cars, and sold stock in the new company only to Henry’s allies. Ford Manufacturing charged Ford Motor high prices for each component, reaping handsome profits while throwing Ford Motor itself into crisis.11

Had Ford and Couzens tried this financial finagling a century later they would have violated laws against corporate self-dealing and found themselves making license plates in a federal prison instead of making cars. But their brazen tactics worked and the dissident investors capitulated, selling all their stock in Ford Motor and leaving Henry with a 58 percent stake of the company. Couzens became the second-largest shareholder with 11 percent. Not long afterward, Ford Manufacturing, a company that had served its purpose, sold all its stock to Ford Motor, and was dissolved. Henry Ford had gained control of his own company and could now develop the car he wanted.

Ford described his dream in a 1906 letter to a magazine calledThe Automobile. The “greatest need today,” he wrote, “is a light, low priced car with an up-to-date engine with ample horsepower . . . powerful enough for American roads and capable of carrying its passengers anywhere that a horse-drawn vehicle will go.”12

Ford walled off the northeast corner on the third floor of the Piquette Street plant, space that is still preserved today, padlocked the door, and set to work with a small team of employees. They started with the Ford Model N and two slightly improved versions, Models R and S. The three had been modestly successful even though they were small, slow, and less than durable on the rutted roads of the day. Henry didn’t trust draftsmen’s drawings, only actual prototype parts that he could test and evaluate. The process was thus time-consuming, involving lots of trial and error. The first running models of the new car were ready by October 1907, but developing the final version would take another year.

In September 1908 Ford himself led the car’s final shakedown cruise, a 1,357-mile trip around Lake Michigan. The group drove up the spine of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, crossed the Straits of Mackinac by ferry, proceeded through the remote wilderness of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and headed down the west side of the lake. They then drove through Chicago’s urban wilderness before returning to Detroit in a car that looked like it had taken a mud bath. But the Model T had made it, suffering only a punctured tire along the way. Ford deemed his creation ready for sale.

When the Model T debuted on October 1, 1908, it wasn’t the cheapest car on the market. The Brush “Everyman’s Car” Runabout cost just $500, which was $350 less than the Model T. But the Brush had a one-cylinder engine and its chassis, axles, and wheels were all made of wood. The Brush’s detractors sniped: “Wooden frame, wooden axles and wouldn’ run.”13

The Model T’s key components, in contrast, were crafted from a new type of steel, vanadium, that was lighter but stronger than traditional carbon steel. “We defy any man to break a Ford Vanadium steel shaft or spring or axle . . . ,” the company’s sales literature boasted.14The car’s four-cylinder engine also had a one-piece block and a detachable head, an unusual design for its day. This made it easy to get inside the engine, which in turn made it simpler to manufacture and repair than most other engines.

Most critically, the Model T was the first car with fully interchangeable parts. If one part failed or was damaged, it could be quickly and cheaply replaced. At 1,200 pounds, the five-passenger touring model weighed 400 to 600 pounds less than comparable cars. Instead of relying on a heavy chassis to withstand primitive roads, the Model T used a light “three-point” chassis and a suspension that flexed with the road, a blessing with certain drawbacks. One joke of the day described a man who named his Model T the Teddy Roosevelt because, he explained, it was the “Rough Rider.”15

The Model T could go up to 40 miles an hour and got nearly 20 miles on a gallon of gas. The driving controls were quirky, but effective. There were two forward speeds and three floor pedals: one for reverse gear, one for the brake, and the third for the clutch. The accelerator was a stalk mounted on the steering column, like a modern turn signal. The car’s construction had no gas gauge, no shock absorbers, and no fuel pump. The carburetor drew in gasoline by gravity. Thus a Model T low on fuel couldn’t climb steep hills because the car’s angle prevented gas from flowing into the engine. The solution was to back up the hill in reverse.

Despite those drawbacks, as word of Henry Ford’s new creation spread, the public reacted with the enthusiasm reserved a century later for iPhones and iPads. Advance orders for 15,000 Model Ts—nearly twice the company’s total sales the previous year—flooded Ford. In May 1909 Ford stopped accepting Model T orders for two months because the backlog was so big. A month later a Model T finished first in a highly publicized cross-country race from New York to Seattle, taking twenty-two days and averaging 7.75 miles an hour. The victory later lost its luster when the car was disqualified because the engine had been replaced during the race, which was a blatant violation of the rules. But by then the publicity bonanza paid off.

The combination of affordability and versatility made the Model T a sensation, bringing car ownership to thousands of people who previously had deemed it beyond their means. A whole new group of companies soon were launched to produce accessories for Ford’s “flivver,” an idiom of the day for a small and inexpensive car. One device had spiked steel wheels that would let a farmer drive his car into his fields to haul a mechanical reaper, and others harnessed the Model T’s engine to saw wood or to pump water. Dozens of smaller attachments came to include one that converted the car’s engine manifold into a cooking grill.

In 1912 the company built nearly 70,000 Model Ts, and the price of the basic two-seat “Torpedo Runabout” model had been cut to $590. A year later, in 1913, Henry Ford unveiled another innovation: the moving assembly line. His engineers had been inspired, in part, by thedisassemblylines of the stockyards of Chicago, where each worker performed a distinct task in cutting up the carcass of a cow. Ford first tried the assembly line concept on the subassembly of components, and found that productivity for those parts immediately surged some 40 percent.16

Ford spread the concept to other subassembly areas: dashboards, engines, and the chassis. He then created a main assembly line for the full car. To simplify production and boost productivity further, the Model T would no longer be available in red, green, gray, and dark blue, as it had been for years. Instead, Ford declared, customers could have the car in “any color they want, as long as it’s black.” Ironically, the exact shade was “Japan black enamel.” Had Henry known what Japanese competitors would do to Detroit decades later, he might have picked a different color.

With sales surging and profits booming, the company next transformed not just the auto industry, but all of America. On January 5, 1914, Couzens summoned reporters to his office and read a statement. Ford Motor, he said, would “reduce the [daily] hours of labor from nine to eight, and add to every man’s pay a share of the profits of the house. The smallest amount to be received by any man 22 years old and upwards will be $5.00 per day.”17Initially the new policy didn’t include women workers. They weren’t deemed to be supporting families, though that policy was changed a couple years later. The same reasoning excluded men under twenty-two, though Couzens announced that “Young men who are supporting families, widowed mothers, younger brothers and sisters, will be treated like those over 22.”18

Couzens, the no-nonsense finance man, championed the $5 day instead of Henry himself, many historians say. Either way, it’s clear that commercial considerations were as important as idealistic ones. Alienation was growing among Ford workers, many of whom struggled to support families on the average Ford wage of $2.34 a day. Turnover at Ford’s Highland Park factory approached 400 percent a year, and the constant cost of training new employees was high. Perhaps most important, Couzens, whose duties included managing sales and distribution, argued that a $5 day would be a masterstroke of marketing.

Other industrialists condemned the move. TheWall Street Journaleditorialized that Ford “has in his social endeavor committed economic blunders, if not crimes. They may return to plague him and the industry he represents, as well as organized society.”19For all its progressiveness, the new pay policy came with paternalistic strings attached. Staffers in the company’s Sociological Department, established just before the $5 day, visited employees’ homes regularly to inspect them for order and cleanliness. Ford and Couzens wanted to be sure workers weren’t squandering their prosperity on liquor, prostitutes, or other dissolute living. Offenders were counseled to mend their ways, and could be fired if they persistently refused.

Couzens proved spot-on about the move’s marketing impact. Even as Henry Ford was on his way to becoming the world’s richest man, the $5 day made him a working-class hero. Letters arrived from grateful workers, thanking Ford because they no longer had to indenture their children as servants to make ends meet. A new boomlet of immigration began. Nearly a century later many elderly Detroiters would describe how their grandparents had left Europe for the lure of the $5 day. Job applicants swamped Ford, and other companies were forced to match Ford’s wages. Ford sold 300,000 Model Ts in 1914, more than four times the number of just three years earlier. Within two years sales more than doubled again, topping 700,000 cars.

The $5 day capped a breathtaking six years during which Henry Ford unleashed enough creativity for two or three lifetimes. During that brief span he created a people’s car, invented mass production, and started paying workers enough to create mass prosperity. The Model T became such a staple of American life that jokes about its foibles spread from coast to coast. TheOriginal Ford Joke Book, published in 1915, included “The Twenty-Third (Ford) Psalm.”

The Ford is my auto, I shall not want another.

It maketh me to lie beneath it.

It soureth my soul.

It leadeth me in the paths of ridicule for its name sake.

Yea, though I ride through the valleys, I am towed up the hills.

And I fear much evil for thy rods and thy engines discomforteth me.

I anoint thy tire with patches. Thy radiator runneth over.

I prepare for blow-outs in the presence of mine enemies.

Surely if this thing follow me all the days of my life,

I will dwell in the bug-house forever.20

By 1915 Henry Ford’s success convinced him that he could do most anything, and his willful eccentricity began taking a bizarre and destructive turn. In December of that year he chartered a ship and sailed with other prominent Americans to Norway in a quixotic effort to mediate Europe’s Great War. The “Peace Ship” mission was as comic as it was controversial. It flopped. The mission also prompted a falling-out with Couzens, who resigned in 1915 and launched a political career that eventually made him a U.S. senator from Michigan.

In 1918 Ford himself ran for the Senate in Michigan, though in a bizarre fashion. He entered both the Republican and Democratic primaries, lost the former but won the latter, and then ran in the general election as a Democrat, even though he had long been a Republican. Despite his enormous wealth he spent almost no money on the campaign. He almost won the election anyway, but was so shocked at his narrow loss that he hired a small army of private investigators to probe possible vote fraud. Nothing came of it. Next Ford turned from politics to publishing, with equally destructive results. He bought his hometown newspaper, theDearborn Independent. It soon started spouting Ford’s nativist anti-Semitism, including his theory that the Jews had started World War I so the gentiles would kill each other.

Meanwhile, in late 1918 Ford declared he would resign as president of Ford Motor, and turn the reins over to his only child, Edsel, who was just twenty-five years old. It was a shocking announcement, but five months later Edsel followed with his own stunner. He also would quit Ford Motor and, with his father, start another, separate car company.

The announcements were a brazen effort to scare Ford’s minority shareholders into selling their shares to Henry Ford. They worked. Henry consolidated his control over Ford Motor by paying $105.8 million to buy all the non-family shares. Couzens got more than $29 million, most of which he later donated to charity. Henry rid himself of nettlesome outside investors and became Ford’s de facto dictator, even though Edsel held the title of president.

As Henry believed the Model T represented the ultimate in automotive evolution, he allowed improvements only slowly and reluctantly. The Model T didn’t get an electric starter to replace its cumbersome hand crank until 1919, seven years after Cadillac introduced the device, and even then Ford made it an extra-cost option. Throughout the early 1920s, more and more of Ford’s managers grew convinced that the Model T was becoming obsolete. Few dared to say that openly. Once, when Henry and his wife took an extended vacation in Europe, some enterprising Ford engineers developed the prototype for a new car and decided to surprise the boss when he returned. When Henry saw the new car he flew into a rage and started tearing it apart, piece by piece, with his bare hands. So much for employee initiative.

For a while it appeared Ford was right to resist change. In 1921, Ford Motor’s share of the U.S. market topped 60 percent, a new record. More than 1.9 million Model Ts were sold in 1923, another record, thanks in part to its amazing versatility. The Model T’s chassis could be adapted to create a host of vehicular variants. Among them was the Lamsteed Kampkar, a $535 bolt-on body that converted Ford’s car into a home on wheels, complete with fold-out beds enclosed with canvas walls, a tank for running water, and a stove for cooking. The Kampkar attachment was manufactured, improbably, by Anheuser-Busch, the brewer, which had entered new businesses after Prohibition became law in 1919.

All the while, Henry Ford continued his basic marketing strategy of making his manufacturing process more efficient, and passing on the benefits to consumers by continually cutting prices. For three straight years, 1924 to 1926, a basic Model T “runabout” with a hand crank instead of an electric starter could be bought for as little as $260, or about $3,500 in today’s dollars.

But after 1923, the peak year, sales of the Model T began a steady decline. Even a styling face-lift in 1926, along with the belated addition of an electric starter as standard equipment to replace the outmoded, dangerous hand crank, couldn’t halt the trend. In dozens of ways, big and small, the car that put America on wheels fell further behind the competition.

Edsel Ford was convinced of the need for a more modern and stylish car, but his father wouldn’t listen. Ironically, Henry Ford wasn’t comfortable with the affectations of America’s new prosperity, which he himself had done so much to create. By 1926 Ford’s market share had dropped below 50 percent. The big winner was GM’s Chevrolet, which was emphasizing comfort, convenience, and prestige as opposed to Ford’s single-minded focus on a low price. Many Americans had come to want status and style, which more and more of them could now afford.

The Twenties weren’t called Roaring for nothing. The bankrupt Duesenberg Automobile & Motors Company was revived under new ownership with a top-of-the-line model costing upward of $20,000—equivalent to $245,000 today. The phrase “It’s a Duesie” entered the language as an expression of admiration, even though Duesenberg would fold during the Depression. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, which had begun the Twenties around 90, closed at 171.75 on May 20, 1927, the day that a young aviator named Charles Lindbergh departed on a solo flight to Paris.

On May 25, five days after Lindbergh’s flight into history, Ford also made history by announcing it would discontinue the Model T. During the prior two decades, more than 15 million Model Ts had been built, a record for any single model that would stand for forty-five years, until another people’s car, made in Germany, would surpass it. Even remote corners of the country mourned the Model T’s passing as sad but inevitable. In North Dakota, theBismarck Tribunewrote: “For years the homely flivver sold as fast as Ford could make them. Then about three years ago there came a change. Slowly at first, then more rapidly, people passed up the flivver for more ornamental machines.”21One such machine in particular pointed the way to the future.

When the television sitcomAll in the Familydebuted in 1971, Archie and Edith Bunker introduced each episode with the show’s theme song, “Those Were the Days.” Many people were mystified, however, by the lyrics of the fourth line: “Gee, our old LaSalle ran great.” It referred to a long-dead and mostly forgotten brand.

LaSalle debuted on March 5, 1927, just eleven weeks before Ford announced the demise of the Model T. The cars weren’t direct competitors—the cheapest LaSalles cost nearly seven times as much as a two-seat Model T runabout—but the two events represented a passing of the guard. As America transformed from a rural to an urban nation, the dull was giving way to the stylish, the practical to the pretentious, and the old-fashioned to the modern.

Other car companies tried to cash in on the trend. In 1927 Studebaker introduced an upscale model called the Dictator, a name intended to suggest that the car would dictate the standard for all other cars to follow. By the mid-1930s, however, it suggested instead images of Mussolini and Hitler, prompting Studebaker to drop the name.

But LaSalles were special. In September of 1927 a newspaper in central Ohio reported on “the escapades of a band of youthful miscreants” from the little town of Delaware who had stolen twenty-five cars over the previous five months and taken them out for joyrides. One was a LaSalle, “which the boys told the sheriff was the ‘spiffiest’ car they had stolen. They told Sheriff Lambert that they intended to steal the LaSalle again for another ride because the car ran so well,” the newspaper reported.22

The young Ohioans lacked common sense, but they had great taste in cars. Thanks partly to LaSalle, General Motors was supplanting the dominance of Ford and would be the world’s largest car company for the next eight decades. And the homespun values of Henry Ford were giving way to the sophisticated sensibilities of a man named Harley Earl.

Harley J. Earl was born in 1893 in circumstances that couldn’t have been more different from the rural roots of Henry Ford. He and his four siblings grew up in a three-story house in Hollywood. One of the family’s neighbors was director Cecil B. DeMille. Young Harley was tall (six foot four), handsome, and athletic, more interested in football, rugby, and track than in academics.

He participated in sports at the University of Southern California and at Stanford, where he sudied prelaw, before dropping out of both schools to work for his father. J. W. Earl owned the Earl Automobile Works, which hand-crafted custom coaches, as automobile bodies were then called. In 1919 J. W. sold his business to a local Cadillac dealer. One of the conditions was that the talented young Harley would stay with the company.

Earl’s designs sported sleek, stylish lines that contrasted with the upright, boxy dimensions of most cars of the day. When some of his creations were displayed at automotive exhibitions in Chicago and New York, they won admiring reviews from several General Motors executives, including the powerful and influential Fisher brothers. The seven brothers had transformed their father’s Ohio blacksmith shop into a company that mass-produced automotive bodies, and in 1919 they sold a 60 percent interest to General Motors. They would sell the remaining 40 percent to GM in 1926, becoming for a time the company’s second-largest shareholders. To this day there is a Fisher Freeway, as well as a Ford Freeway, in Detroit.

In December 1925, a few days before Christmas, Larry Fisher, the head of GM’s Cadillac division, phoned Earl in Los Angeles. Cadillac wanted to develop sportier, more youthful luxury cars, he explained, to compete with rival Packard, which was luring young, well-heeled buyers away from Cadillac. But GM’s engineers seemed incurably wedded to the dull and stolid styling that resembled, well, many Cadillac owners themselves. Would Earl become a consultant for Cadillac, Fisher asked, and try his hand at designing something different?

On January 6, 1926, thirty-two-year-old Harley Earl boarded a train in Los Angeles for Detroit. For the next three months he buried himself in the design and development shops of the Cadillac plant on the city’s southwest side. That spring he presented his work to GM’s Executive Committee, including CEO Alfred P. Sloan Jr. Instead of simply displaying his drawings, however, Earl staged a showing worthy of a Hollywood impresario.

He unveiled four full-sized models of his designs, sculpted from clay applied over wooden frames. Painted with black enamel and finished with a shiny coat of clear varnish, they had a wet and luscious look. The GM bosses circled around the models again and again. “Get Earl over here so everyone can meet him,” Sloan said.

With the young designer summoned, Sloan announced: “Earl, I thought that you’d like to know that your design has been accepted!” He then suggested to Larry Fisher that Cadillac reward Earl with a trip to the upcoming Paris Auto Show. The beaming Fisher replied: “Mr. Sloan, I already have his ticket!”23

Paris was a fitting reward, because Earl had drawn inspiration from French cars, particularly the Hispano-Suiza. Like the “Hisso,” Earl’s models featured prominent vertical front grilles and louvered vents along each side of the hood, creating a longer, more horizontal stance. From every angle the clay models had interesting lines that invited a closer look. They appeared elegant without seeming overbearing and compact without looking cramped. The designs provided just what the GM bigwigs wanted: a youthful and sporty flavor to broaden the prestigious but stuffy Cadillac line. Earl’s designs were so different that, while GM decided to sell them in Cadillac dealerships, the company gave them their own marque: LaSalle. The names fit. Both Cadillac and La Salle were early French explorers in America. Cadillac was the founder of Detroit while La Salle claimed the territory of Louisiana, before being murdered by his own men. That fit, too, as Harley Earl’s management style would prove.

Alfred Sloan found Harley Earl at just the right time. Sloan had taken the helm at GM in 1923, just a few years after the company had survived a brush with bankruptcy under the reckless leadership of its founder, William “Billy” Durant. Sloan concluded that he couldn’t beat Henry Ford at his own game of constantly cutting costs. He decided to change the game instead. He outlined his strategy in a letter to shareholders in GM’s 1924 annual report. General Motors, he wrote, would “build a car for every purse and purpose.” Instead of adhering to Henry Ford’s “once size fits all” philosophy, GM would create a hierarchy of brands. Most buyers would start with the practical and inexpensive Chevrolet and hopefully graduate to Pontiacs, Oldsmobiles, and Buicks, and eventually those who climbed America’s ladder of social and financial success would buy Cadillacs.

What Henry Ford had done for mass manufacturing Alfred Sloan would do for mass marketing. Ironically, Sloan’s personality lacked any hint of marketing flamboyance; he was as stiff and cerebral as the starched high white collars on the shirts that he wore every day. It took a strait-laced, no-nonsense businessman to spot the enormous potential in selling to people’s pretensions. Sloan and Earl were a perfect match.

A year after Sloan approved Earl’s designs, the first LaSalles were unveiled to the public at the Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston. The guests followed white-coated musicians into the ballroom, where the daughter of a Boston Cadillac dealer launched the new car like it was a ship, breaking a bottle of champagne on its radiator. “Lovely creation of many minds and hearts and hands, go forth into the highways and byways of the world,” she intoned. “I christen thee, LaSalle.”24

There were six body styles, ranging from the two-passenger roadster with a rumble seat priced at $2,495 to a five-passenger sedan priced at $2,685—competitive with Packard, and some $500 less than the least expensive Cadillac. The sedan’s styling was traditional, prompting theNew Yorkerto sniff that it was “squarish, ample, redolent of the suburban family . . . a concession to the Rotarian market.” The magazine was more impressed, however, with the LaSalle coupes and convertibles, adding that “the line, as a whole, is as refreshing as a Paris frock in a Des Moines, Iowa, ballroom.”25GM would use the magazine’s praise in LaSalle advertising, without the reference to Des Moines.

The LaSalles had more than just pretty grilles. Their technical capabilities were impressive. Every LaSalle came with a 75-horsepower V8 engine at a time when V8s connoted luxury on American roads. In May 1927 a GM mechanic piloted a LaSalle around the company’s Michigan Proving Ground while averaging just over 95 miles an hour for nearly 952 miles, qualifying the LaSalle to be the pace car in that year’s Indianapolis 500. It was a remarkable feat, considering that a 160-horsepower Duesenberg won the race that year averaging only two miles an hour faster over half the distance.

LaSalles proved especially popular with the small but growing ranks of women drivers. “LaSalle is a graceful car, with a great deal of charm for the female eye on account of its smart lines,”Voguereported, describing women driving LaSalles.26In Los Angeles, actress Clara Bow, sex symbol of the silent-film era, was regularly photographed in her 1927 LaSalle roadster.

Women found LaSalles easy to handle because their wheelbase was seven inches shorter than that of the smallest Cadillac. Also, the gear ratios allowed LaSalles to turn many corners without downshifting, minimizing an aspect of driving that many women hated. “The LaSalle obeys the feminine hand instantly, with only the slightest effort,” declared one advertisement aimed at women, which was unusual for its day.27Other ads carried French headlines, such as “La Nouvelle Arrivee” or “Bon Voyage.” GM sold nearly 27,000 LaSalles the first year, a success by any measure. General Motors had a new brand and, before long, a new executive: Harley Earl.

From the 1930s through the 1950s, designers at General Motors would recite a little ditty that went:

Our father, who art in styling,

Harley be thy name.

It was about the only time they called the boss Harley instead of Mr. Earl, which they invariably pronounced as “Misterl,” as if one word. But Harley Earl wasn’t merelyinstyling. Hewasstyling.

So impressed was Sloan with Earl’s work on the LaSalle that in the summer of 1927, just a few months after the launch of the new line, the CEO brought a high-level personnel matter before GM’s Executive Committee. Harley Earl, Sloan proposed, should be hired full-time as head of a small but important new corporate staff, the Art and Colour Section (with the British spelling of “colour”). There was nothing else like it in America’s adolescent automobile industry.

Earl and his designers would make design an integral part of the process of car development at General Motors, and thus give the company an edge over its more pedestrian competitors. Earl had to move from balmy Los Angeles to a place that seemed to have two seasons: winter, and winter-is-coming. At age thirty-three he transported his young family to Detroit, settling in the highbrow suburb of Grosse Pointe.

Settling into General Motors proved more difficult. Earl had no experience working in large organizations filled with fiefdoms, executive intrigue, and office politics. Fisher Body, the division that stamped out the sheet metal for the cars Earl designed, was a semiautonomous satrapy, and neither the Fisher brothers nor their underlings brooked much interference. Sometimes they summarily altered Earl’s designs, claiming that his specifications would compromise the structural integrity of the cars or would increase production costs.

In 1929 GM launched a new Buick sedan, designed by Earl, with styling that flared outward at the “belt line,” the imaginary line just below the car’s windows. Walter Chrysler, a former GM executive turned competitor, described the car as a “Pregnant Buick.” The name stuck. Buick’s sales plunged more than 25 percent that year, even before the stock market crash.

The fiasco sparked a finger-pointing war. The Fishers claimed they had executed Earl’s design faithfully. Earl retorted that the Buick’s belly bulge was unauthorized and took to calling the Fishers, short men who wore old-fashioned homburg hats, “the Seven Dwarfs.”28Meanwhile, he insisted on approving any design changes, and hired a couple of engineers to work on his own staff so he wouldn’t be hoodwinked by the metal-benders at Fisher Body.

Earl also invoked his personal relationship with Sloan to settle arguments. “Let’s see what Alfred thinks about this,” he would declare, but only rarely did he place the call. It was clear that Earl’s power emanated from Sloan. In 1937, after a decade at GM, Earl was promoted to vice president, and the Art and Colour Section became the General Motors Styling Department. With his status enhanced, Earl formalized the structure within his domain.

He created separate, locked styling studios for each GM division—Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, and Cadillac/LaSalle—reserving access to all of them for himself alone. He wanted his designers to compete with one another. All the while, styling took on added importance as the practice of putting reshaped sheet metal on the same old mechanical underpinnings became the annual model change. Henry Ford disdained the practice, but GM and Earl led the way. Planned obsolescence brought people into showrooms, and showroom traffic sold cars.

In 1938 Earl designed the first futuristic “dream car,” a vehicle intended not for production but simply for making a styling statement and creating buzz. It was the Buick Y-Job, a name inspired by experimental aircraft. It featured a sleek, low body; hideaway headlamps; prominent chrome bumpers; and a horizontal front grille that contrasted with the typical vertical grilles of the day.

The Y-Job served both as Earl’s personal car—he drove it to and from work for years—and his personal statement. “My primary purpose,” he would say, “has been to lengthen and lower the American automobile, at times in reality and always at least in appearance.”29He also had a more pithy expression of his design philosophy: “If you drive by a schoolyard and the kids don’t whistle, go back to the drawing board.”30

Harley Earl had left Hollywood, but Hollywood hadn’t left Harley Earl. His various offices at GM were studio sets, in effect, with Earl himself cast as the star. Dark paneling lined offices crowned with beamed ceilings and floored with plush Oriental carpets. The boss’s desk was set on a raised dais, so he was always talking down to those who sat before him.

Most GM executives dressed with all the flair of an asphalt parking lot—dark suits with thin, dark ties and white shirts. But not Harley Earl. He wore bespoke suits of tan, gray, or even white, brightly colored silk shirts and ties, a matching pocket hankie, and matching shoes of suede or soft leather. He kept identical sets of clothes in his office closets so he could change at noon, always looking pressed and fresh even as others wilted in Michigan’s midsummer, pre-air-conditioning humidity. With his height, broad shoulders, pale blue eyes, and fair skin that often sported a just-right Florida tan, Earl cut an imposing figure.

He would stalk the halls of his studios until 10 p.m. or midnight, assessing the work that would make or break men’s careers. He often judged the drawings of his designers by having them stand around him in a semicircle while he sat cross-legged in front of their work, pointing the toe of his butter-soft shoe at features he liked. Focus groups and marketing surveys hadn’t been invented yet (though when they were, their benefits would be dubious). Earl relied on instinct. After he designed the LaSalle he rarely, if ever, sketched new cars himself, always leaving that task to underlings.

“You were always a little bit in terror of Mr. Earl,” a longtime Cadillac designer, Dave Holls, wrote in his memoirs. “I think he loved it.” Once, early in his career, Holls stood nearby while Earl discussed a new design with Cadillac’s studio chief. Earl asked: “Why don’t we ask some of the young fellows, and see what they like?” Holls was asked for his opinion, spoke his mind, and then learned that Earl had a different opinion. “If I want the young fellow to say anything,” Earl snapped, “I’ll ask him.” For the next two weeks, Holls feared he would be fired.31

So did another young designer who, in the midst of Earl’s long career, spotted his boss one day striding toward the executive parking garage with two big packages under his arm. “How are you, Misterl?” the designer blurted out. “I see you just cashed your check!” Earl stopped and glared hard before striding away, leaving the gulping man relieved that he hadn’t been fired on the spot.32

Others weren’t so lucky. Bill Mitchell, Earl’s longtime second-in-command and eventual successor, tried once to intercede with the boss on behalf of two colleagues whose spirits crumbled under Earl’s constant criticism. “A couple of fellas, you just scared them to death,” Mitchell confided to Earl one evening after work. “They’re going to psychiatrists.” Earl listened with apparent sympathy and said, “I’m glad you told me that.” But a couple days later he summoned Mitchell and barked: “Goddam son of a bitch, [if] they don’t like the work, throw their asses out of here.” The two stylists were fired.33

While Harley Earl was cementing his ascendancy at General Motors, his LaSalle fared less well. The Great Depression caused people who previously could afford luxury cars to settle for something less. By 1933 LaSalle advertisements, in a nod to the nation’s prevailing frugality, touted the car’s durability as well as its prestige. Still, LaSalle sales plunged that year to just 3,500 cars even though the price had been cut to $2,235, 10 percent below the price of 1927.

Rumors spread that the LaSalle line would be axed. But when GM’s top brass gathered to review the designs of the new 1934 models, Earl addressed the issue head-on. “Gentlemen, if you decide to discontinue the LaSalle,” he said, “this is the car that you are not going to build.”34The curtains drew back to reveal a stunning new design.

The car’s new lines were longer and more rounded than before. The grille had been narrowed to look like a tall tower. Each side of the hood had five round portholes. A stylish abstract ornament, suggesting a bird taking flight, sprouted atop the elongated hood. In a bow to commercial reality, the 1934 LaSalles borrowed engines and other key components from GM’s lower-priced Oldsmobile division to reduce production costs. The tactics worked. GM sold 7,200 LaSalles in 1934, more than double the year before. Three years later, in 1937, LaSalle sales hit a record 32,000 cars. That year LaSalles got Cadillac engines again, and louverlike stainless-steel strips to replace the hood portholes. To fuel sales, LaSalle prices were cut to as low as $1,000, depending on the body style. Nineteen thirty-seven marked LaSalle’s apogee, but the success didn’t last.

LaSalle sales dropped sharply in 1938. By that time, LaSalles had grown big enough to serve as less costly substitutes for Cadillacs. In Buffalo, New York, for example, the Paske family—father, mother, and five sons—would pile into their 1939 LaSalle sedan and motor across the state to Lake George for family holidays. Raymond, the middle son, had to sit on the floor of the backseat, dodging his brothers’ feet and inhaling exhaust fumes. But all seven Paskes and their vacation luggage fit snugly into the LaSalle.35“It was becoming increasingly clear to GM that the LaSalle and Cadillac had become practically the same thing,”Automobile Quarterlymagazine later observed. “One of them had to go.”36The 1940 LaSalles would be the last in the line.

By then the world was at war, even though it would be nearly two years before America joined the fray. During World War II civilian car production would cease. America became the “Arsenal of Democracy,” Detroit’s factories converted to produce airplanes, tanks, troop haulers, and a quirky military vehicle called the jeep. Automobiles stopped signaling trends in American culture until the dawn of a new decade, the 1950s.

But the two cultural strains—the simple versus the stylish, the practical versus the pretentious—established by the Model T and by the LaSalles would endure and evolve. Henry Ford had sold to the head; Harley Earl sold to the heart. The two men’s cars captured opposing values that would define fault lines in American society for decades. They would gain expression in future generations of vehicles as the pace of cultural change in America accelerated in the Fifties, the Sixties, and beyond.

“I have in my office a scale model of the first sedan I ever designed for the company, a 1927 LaSalle V-8,” Earl wrote in 1954.37“I have a great affection for the old crock, but I must admit it is slab-sided, top-heavy and stiff-shouldered.” Indeed, by that time automobile styling had evolved. And Harley Earl was creating some of the most powerful totems of America’s affluent and optimistic postwar era: the Corvette, chrome-slathered cars, and tail fins.