What is included with this book?

| Preface | p. vii |

| Introduction: A Head That Throbbed Heartlike: The Philosophical Mind of David Foster Wallace | p. 1 |

| The Background | |

| Introduction | p. 37 |

| Fatalism | p. 41 |

| Professor Taylor on Fatalism | p. 53 |

| Fatalism and Ability | p. 57 |

| Fatalism and Ability II | p. 61 |

| Fatalism and Linguistic Reform | p. 65 |

| Fatalism and Professor Taylor | p. 69 |

| Taylor's Fatal Fallacy | p. 79 |

| A Note on Fatalism | p. 85 |

| Tautology and Fatalism | p. 89 |

| Fatalistic Arguments | p. 93 |

| Comment | p. 107 |

| Fatalism and Ordinary Language | p. 111 |

| Fallacies in Taylor's "Fatalism" | p. 127 |

| The Essay | |

| Renewing the Fatalist Conversation | p. 135 |

| Richard Taylor's "Fatalism" and the Semantics of Physical Modality | p. 141 |

| Epilogue | |

| David Foster Wallace as Student: A Memoir | p. 219 |

| Appendix: The Problem of Future Contingencies | p. 223 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Copyright information

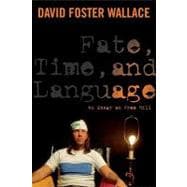

An excerpt from "A Head That Throbbed Heartlike: The Philosophical Mind of David Foster Wallace," James Ryerson's introduction to Fate, Time, and Language .

One of the impressive aspects of Wallace's achievement was that he was able to sustain his focus on the philosophy thesis long after having begun a countervailing transformation: from budding philosopher to burgeoning novelist. The transition was set in motion a few years earlier, toward the end of his sophomore year, when a bout of severe depression overcame him. He left school early and took off the following term. Wallace would suffer from depression for much of his life, and he tended to avoid public discussion of it. On a rare occasion in which he did allude publicly to his hiatus from Amherst, in his interview with McCaffery about a decade later, he described the episode as a crisis of identity precipitated by mounting ambivalence about his future as a philosopher. "I was just awfully good at technical philosophy," he said, "and it was the first thing I'd ever been really good at, and so everybody, including me, anticipated I'd make it a career. But it sort of emptied out for me somewhere around age twenty."

A debilitating panic followed. "Not a fun time," he went on. "I think I had a kind of midlife crisis at twenty, which probably doesn't augur well for my longevity." He moved back home to Illinois, "planning to play solitaire and stare out the window," as he put it -- "whatever you do in a crisis." Though he now doubted that he should devote his life to philosophy, he was still drawn to the topic and found ways to engage with it, even dropping in on a few of his father's lectures at the university, where he monopolized the discussion. "He came to some of my classes in aesthetics, and tended to press me very hard," James Wallace told me. "The classes usually turned into a dialogue between David and me. The students looked on with 'Who is this guy?' looks on their faces."

During this time, Wallace started writing fiction. Though it represented a clean break from philosophy, fiction, as an art form, offered something comparable to the feeling of aesthetic recognition that he had sought in mathematical logic -- the so-called click. "At some point in my reading and writing that fall I discovered the click existed in literature, too," he told McCaffery. "It was real lucky that just when I stopped being able to get the click from math logic I started to be able to get it from fiction." When he returned to Amherst, he nonetheless resumed his philosophical studies (eventually including his work on Taylor's "Fatalism"), but with misgivings: he hoped he would ultimately be bold enough to give up philosophy for literature. His close friend Mark Costello, who roomed with him at Amherst (and also became a novelist), told me that the shift was daunting for Wallace. "The world, the reference, of philosophy was an incredibly comfortable place for young Dave," he said. "It was a paradox. The formal intellectual terms were cold, exact, even doomed. But as a place to be, a room to be in, it was familiar, familial, recognized." Fiction, Costello said, was the "alien, risky place."

Wallace's solution was to pursue both aims at once. His senior year, while writing the honors thesis in philosophy, he also completed an honors thesis in creative writing for the English Department, a work of fiction nearly 500 pages long that would become his first novel, The Broom of the System , which was published two years later, in 1987. Even just the manual labor required to produce two separate theses could be overwhelming, as suggested by an endearingly desperate request Wallace made at the end of his letter to Kennick. "Since you're on leave," he wrote, "are you using your little office in Frost library? If not, does it have facilities for typing, namely an electrical outlet and a reasonably humane chair? If so, could I maybe use the office from time to time this spring? I have a truly horrifying amount of typing to do this spring -- mostly for my English thesis, which has grown Blob-like and out of control -- and my poor neighbors here in Moore are already being kept up and bothered a lot."

Despite the heavy workload, Wallace managed to produce a first draft of the philosophy thesis well ahead of schedule, before winter break of his senior year, and he finished both theses early, submitting them before spring break. He spent the last month or so of the school year reading other students' philosophy theses and offering advice. "He was an incredibly hard worker," Willem deVries told me, recalling the bewilderment with which he and his fellow professors viewed Wallace. "We were just shaking our heads." By the end of his tenure at Amherst, Wallace decided to commit himself to fiction, having concluded that, of the two enterprises, it allowed for a fuller expression of himself. "Writing The Broom of the System , I felt like I was using 97 percent of me," he later told the journalist David Lipsky, "whereas philosophy was using 50 percent."

Given his taste for experimental fiction, however, Wallace didn't assume, as he prepared to leave Amherst, that he would be able to live off of his writing. He considered styling himself professionally after William H. Gass, the author of Omensetter's Luck (a novel Wallace revered), who had a Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell and whose "day job" was teaching philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis. Wallace toyed with applying to Washington University for graduate school so he could observe Gass firsthand. But in the end, he chose to attend the University of Arizona for an M.F.A. in creative writing, which he completed in '87, the same year he published The Broom of the System and sold his first short-fiction collection, Girl with Curious Hair .

Even with those literary successes, however, Wallace soon suffered another serious crisis of confidence, this time centered around his fiction. He later described it as "more of a sort of artistic and religious crisis than it was anything you might call a breakdown." He revisited the idea that philosophy could provide order and structure in his life, and that year he applied to graduate programs at Harvard and Princeton Universities, ultimately choosing to attend Harvard. "The reason I applied to philosophy grad school," he told Lipsky, "is I remembered that I had flourished in an academic environment. And I had this idea that I could read philosophy and do philosophy, and write on the side, and that it would make the writing better."

Wallace started at Harvard in the fall of '89, but his plan quickly fell to pieces. "It was just real obvious that I was so far away from that world," he went on. "I mean, you were a full-time grad student. There wasn't time to write on the side -- there was 400 pages of Kant theory to read every three days." Far more worrisome was the escalation of the "artistic and religious crisis" into another wave of depression, this time bordering on the suicidal. Late that first semester, Wallace dropped out of Harvard and checked into McLean Hospital, the storied psychiatric institution nearby in Massachusetts. It marked the end of his would-be career in philosophy. He viewed the passing of that ambition with mixed emotions. "I think going to Harvard was a huge mistake," he told Lipsky. "I was too old to be in grad school. I didn't want to be an academic philosopher anymore. But I was incredibly humiliated to drop out. Let's not forget that my father's a philosophy professor, that a lot of the professors there were revered by him . That he knew a couple of them. There was just an enormous amount of terrible stuff going on. But I left there and I didn't go back."

Though Wallace abandoned it as a formal pursuit, philosophy would forever loom large in his life. In addition to having been formative for his cast of mind, philosophy would repeatedly crop up in the subject matter of his writing. His essay "Authority and American Usage," about the so-called prescriptivist/descriptivist debate among linguists and lexicographers, features an exegesis of Wittgenstein's argument against the possibility of a private language. In Everything and More , his book about the history of mathematical ideas of infinity, his guiding insight is that the disputes over mathematical procedures were ultimately debates about metaphysics -- about "the ontological status of math entities." His article "Consider the Lobster" begins as a journalistic report from the annual Maine Lobster Festival but soon becomes a philosophical meditation on the question, "Is it all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure?" This question leads Wallace into discussions about the distinction between pain and suffering; about the relation between ethics and (culinary) aesthetics; about how we might understand cross-species moral obligations; and about the "hard-core philosophy" -- the "metaphysics, epistemology, value theory, ethics" -- required to determine the principles that allow us to conclude even that other humans feel pain and have a legitimate interest in not doing so.

Those are just explicit examples. Wallace's writing is full of subtler philosophical allusions and passing bits of idiom. In Infinite Jest , one of the nine college-application essays written by the precocious protagonist, Hal Incandenza, is "Montague Grammar and the Semantics of Physical Modality" -- a nod to Wallace's own philosophy thesis. A story in his short-fiction collection Oblivion , "Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature," shares its title with the 1979 book of anti-epistemology by the philosopher Richard Rorty. The story "Good Old Neon" invokes two conundrums from mathematical logic, the Berry and Russell paradoxes, to describe a psychological double bind that the narrator calls the "fraudulence paradox." At the level of language, Wallace's books are peppered with phrases like "by sheer ontology," "ontologically prior," "in- and extensions," "antinomy," " techne ."

Perhaps the most authentically philosophical aspect of Wallace's nonfiction, however, is the sense he gives his reader, no matter how rarefied or lowly the topic, of getting to the core of things, of searching for the essence of a phenomenon or experience. His article on the tennis player Roger Federer delves into the central role of beauty in the appreciation of athletics. His antic recounting of a week-long Caribbean cruise penetrates beneath the surface of his own satirical portrait to plumb a set of near-existential issues -- freedom of choice, the illusion of freedom, freedom from choice -- that he saw lurking at the heart of modern American ideas of entertainment. "I saw philosophy all over the place," DeVries, his former professor, said of Wallace's writings. "It was even hard to figure out how to single it out. I think it infuses a great deal of his work."

...

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Published by Columbia University Press and copyrighted © 2011 by Columbia University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. For more information, please visit the permissions page on our Web site.