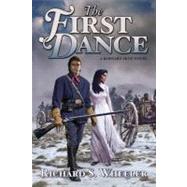

RICHARD S. WHEELER is the author of more than fifty novels of the American West. He holds five Spur Awards and the Owen Wister Award for lifetime contributions to the literature of the West. He lives in Livingston, Montana, near Yellowstone Park, and is married to Sue Hart, an English professor at Montana State University in Billings.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.