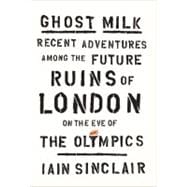

Iain Sinclair is the author of many books, including Downriver, Lights Out for the Territory, London Orbital, and Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire. He lives in Hackney, East London.

“An astonishingly original and entertaining writer.” —Michael Dirda, The Washington Post

“Sentence for sentence, there is no more interesting writer at work in English.” —John Lanchester, The Daily Telegraph

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.