What is included with this book?

| Foreword by James R. Gavin III, MD, PhD | ix | ||||

| Part One: BEFORE | |||||

|

3 | (18) | |||

|

21 | (16) | |||

|

37 | (24) | |||

|

61 | (16) | |||

|

77 | (18) | |||

|

95 | (12) | |||

|

107 | (10) | |||

| Part Two: AFTER | |||||

|

117 | (28) | |||

|

145 | (16) | |||

|

161 | (8) | |||

|

169 | (20) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 189 | (8) | |||

| Resource Guide by Tamara Jeffries | 197 | (38) | |||

| Index | 235 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

- 1 -

Grocery Shopping Was Disneyland

My dad was in the kitchen at o'dark-thirty on Sunday mornings, organizing cayenne, black pepper, salt, paprika, and other spices; mincing garlic, onion, bell pepper; and cubing pork, pork fat, and beef. He was in his glory -- making his signature link sausages.

If six- or seven-year-old me scrambled up and begged to help, Daddy let me add a pinch of this or that, mix

the meat with my little hands, and maybe, just maybe, hold casings as he fed the meat mix into the grinder.

That sausage was the centerpiece of our Sunday breakfast, likely to include grits, slab bacon, salmon croquettes, buttermilk biscuits, smothered potatoes, and fresh-squeezed OJ.

Around seven thirty, Momma had her brood heading out the door, primed to put our nickels in the offering plate and sing Jesus-loves-me hymns. In addition to me, that brood consisted of Paula, two and a half years older than me; Michael, fifteen months my junior; Fred, nineteen months younger than Michael; Marcia, eleven months younger than Fred; and Brenda, eleven months younger than Marcia.

Daddy stayed behind to clean up the kitchen and then go back to bed with Ohio's oldest black newspaper, the legendary ClevelandCall & Post.Whenever anyone questioned why he didn't go to church but insisted that his children attend faithfully, he said, "Well, just in case there is a GOD, I want my children to be protected."

There was no such thing as a typical Sunday dinner in our home. Each one had to be different -- if not better -- than the last. You wouldn't catch us having roast chicken on back-to-back Sundays. Chicken, maybe, but not prepared the same way. Momma could serve up ninety-five varieties. My favorite was what I called her "red chicken" -- aka chicken cacciatore -- with its sweet homemade tomato sauce graced with fresh basil and other herbs, especially garlic. We ate a lot of garlic. I don't know if Momma knew about the benefits of herbs, I just know she loved them. She also loved spices from all around the world: cinnamon from Madagascar, chilies from Mexico. She usually reserved her adventures with new spices for Sunday dinners.

Whenever we kids were introduced to a new spice or dish from a foreign country, we had to look it up in the dictionary, find it on our globe, and read up on it in our set of encyclopedias. The kitchen was my gateway to geography. I knew where Madagascar was! My parents were avid about our education, and ours started in the kitchen. It was in the kitchen that I got my first taste of math -- learning to work with measuring cups and spoons, to double or halve a recipe, and to distinguish between dry and liquid measurements.

Sunday dinner was also for putting a spin on an old standby. Instead of middle-America mashed potatoes to go with that standing rib roast, Momma might rather make garlic mashed potatoes with mushrooms and chives. OK! And they were jamming! Momma was always working her culinary skills with her blender, ricer, slicers, dicers -- she even had a Kabob-It, an electric tabletop shish-kebab maker. She turned all her daughters into gadget fanatics like herself. To this day, I have to stay clear of the shopping channels, because I would own every gadget they hawk.

When holidays came around, like most American families we went into a food frenzy. We may have even out-frenzied most families, especially when it came to Thanksgiving. Three menus were the norm, finished off with a spread of sweet things to rival any bakery.

We had the traditional menu: roast turkey with oyster-and-giblet dressing; collards or a mustard-and-turnip-greens mix; macaroni and cheese casserole (longhorn and sharp cheddar aged to perfection); cranberry sauce (whole berries and jellied); and homemade cloverleaf rolls. Momma had to make dozens and dozens of rolls because over the course of the day, I could eat a dozen by myself -- shoot, we all could. They were melt-in-your-mouth yumptious rolls to spread with sweet butter, sop gravy, or dip in warm honey.

Menu #2 was the "Specialty Dinner." Time to get fancy-fancy! Possibilities included roast duck, filet mignon, or a gourmet fish dish, with a couple or three side dishes, such as double-cheesy scalloped potatoes, fried-corn succotash with tomatoes and onions, or asparagus with wild mushrooms. And gravy for our veggies.

Menu #3 was the we-don't-give-a-damn-about-weight-disease-or-death menu: slow-cooked, spiced-just-right chitlins. When I researched the dish and found the correct pronunciation, I rode everybody who called them chitlins as opposed

to chitterlings. To no avail. In my home, they had to be "chitlins" -- fifty pounds at minimum -- with hog maws mixed in. My sister Paula and brother Michael were the chitlin pickers. They sat at the sink for hours just pulling and picking poop off the hog intestines. People said that Michael "could clean a chitlin so well you could hear it squeak." I did not care who cleaned them; I refused to eat them. Everybody wanted my helping of that stinking food -- always served piping hot and with hot sauce. I had no problem with the rest of the meal: spaghetti with meatballs, coleslaw, and baked or hot-water corn bread.

When my maternal great-grandmother lived with us, the hot-water corn bread was her contribution. And it took her all day to make it. She was slow-moving, and her eyesight was poor. I was her helper in the kitchen. The rest of the kids did not want to be in there with her because she was old, repeated herself, dipped snuff, chewed tobacco, and could and would spit that icky brown tobacco juice clean across the room into her spittoon. But I enjoyed her company and learned a lot from her history. She had met the self-made millionaire Madam C. J. Walker when the Madam came to the Midwest to teach "colored" women about hair care. Great-grandma also told me stories about growing up with Jim Crow in Water Valley, Mississippi, and about her migration from the South. I remember feeling so glad that I had not been born where and when she was. Not that I ever knew exactly when that was. During the few years that I knew her, Great-grandma declared herself eighty-eight, birthday after birthday.

I loved the woman, but I did not like her contribution to the Thanksgiving dinner dessert menu: molasses bread. It seemed to swell in your stomach and sit for days. And if you didn't like molasses bread, or key lime pie, or my personal favorite, German chocolate cake, you could take your pick: sweet potato pie, peach cobbler, minced meat pie, pound cake, cheesecake, cupcakes.

Preparation for Thanksgiving dinner commenced on the Monday before. All hands on deck! I was in the "low work" detail: tasks designated for the short kids. That included cleaning out the pantry, cabinets, and fridge for the new stuff coming for the celebration and getting out pots, pans, and other tools for those in the "high work" detail. They did the cutting, chopping, freezing, seasoning, and cleaning of chitlins, among other things.

As everyone did his or her part, there was laughing, singing, and sometimes fussing. Relatives and friends started coming by on that same said Monday after work to help or to just hang out. Most would bring booze; and some would bring treats for the kids. Before long, the grown-ups got a game of bid whist going. Such was our home for the next few days as we all got our mouths tuned up for the grand sit-down at two o'clock on Thursday.

We gave thanks by going back for seconds, thirds. And we always had a house full of folks. A parade of friends, kin, and pretend kin showed up to load up. Strangers, too: people a friend or relative brought along or somebody our mother adopted during the holidays. One Thanksgiving morning we woke up to find a young woman with two small boys and an infant son in our living room. OK, who were these people? Some lady who was down on her luck. Apparently, one of my cousins was the new baby's daddy. Momma felt obliged to make sure the beleaguered family at least had a happy Thanksgiving. (They stayed until right after Easter.)

After all the grown-ups had eaten to capacity, those who did not nod off were likely to be up for a "taste." A taste of Dewar's, Jack Daniel's, or Johnnie Walker Red Label. They said they needed something for the liquor to land on -- the reason they ate so much, they claimed. Well, when the liquor landed, the grown-folks became really funny and our home all the louder.

When it came to Christmas dinner, as with Thanksgiving, you would have thought that we were running a restaurant. That dinner also took about a week to work up and included a standing rib roast complete with the little chef hats, which Momma made, and ornately decorated three- and four-layer cakes. For New Year's Day, we kept it simple: roast pork loin -- the whole long thing -- parsley potatoes, gravy, corn bread, and, of course, a monster pot of black-eyed peas for good luck. And maybe only two desserts. We could actually cook Easter dinner in one day. Typically: ham, potato salad, string beans, rolls, and only one dessert. And Kool-Aid. We had Kool-Aid with every lunch and dinner, with every snack. Kool-Aid was the first thing we children learned to make. We probably went through twenty-five pounds of sugar a week just for the Kool-Aid alone.

Whatever the meal, our parents frowned upon most all foods that came in a box or can, and anything labeled "instant." Just about everything we ate was fresh and made from scratch, be it for a holiday or workaday dinner -- six o'clock sharp! -- such as Monday's fried chicken, white rice, and salad; Tuesday's spaghetti and salad; Wednesday's beef Stroganoff and green peas; or Thursday's liver and onions with white rice, plenty of gravy, and steamed spinach. On Friday, white rice again, salad with way too much stuff in it to be healthy, and, oh, yes, here comes the fish: treated to a flour-and-cornmeal batter, then lard fried in a black cast-iron skillet. (I still have that skillet.) Most of the fish we ate had sturdy bones. We kids learned early on how to eat fish like that. Yeah, we choked sometimes, though not often.

Come Saturday morning, our family was back at the table for a big breakfast. It wasn't as big as a Sunday breakfast, but we had big bowls of cereal, lots of whole milk, and a loaf of toasted white bread. Saturday had its own happening, though: Daddy's homemade donuts. In a pot big enough to deep-fry a suckling pig, he made maybe six or seven dozen donuts for the family and for friends. He made donuts with fillings -- sometimes apple butter, sometimes marmalade, jelly, or preserves. He made donuts coated with powdered sugar, drizzled with chocolate sauce, or shining with a glaze. (I swear Krispy Kreme stole my daddy's glazed donut recipe!)

As you've probably deduced by now, my family lived to eat. We loved to eat. Food was our familiar, our household god. My earliest memory of a chapter of tragic family history was the story of my father's only brother, Fred, dying a horrible death. It wasn't a head-on collision or a shark attack or a jealous husband with a switchblade. Uncle Fred, who had fallen on hard times, had starved to death. Of all the ways to exit the planet, to go out hungry was, for my family, one of the most frightening. My parents were bound and determined that would never happen to them or their children. We never went to bed hungry, never saw our cupboards bare, never wondered if we would eat another day. Food was like the sun: we knew it would come out tomorrow.

We lived lives of relative plenty in a four-bedroom cookie-cutter red-brick row-type house in Carver Park Estates -- a fancy name for one of the projects in Ohio's "Mistake on the Lake," aka Cleveland. In the projects' hierarchy, we were in the upper echelon. I guess that made us upper working class. Both my parents had good jobs. Daddy was a trucker for Carling Brewery, of "Hey Mabel, Black Label!" fame. Momma worked full-time at the post office and part-time as a nurse at St. Vincent's Charity Hospital. When it came to clothes, we always had up-to-the-minute fashions and accessories. I have no memory of hand-me-downs. Our Easter outfits, custom made by Momma, were so fine that we were inevitably tapped to head up our church's Easter parade. But food, that was our pride. Food was how we celebrated ourselves. And grocery shopping was Disneyland.

On Saturdays we rose before first light, ate breakfast, piled into our gray and white Chevy something, and off we went on a long ride to get the best fruits in season and the most colorful vegetables out in the country. I remember picking strawberries from a strawberry patch and grapes off the vine. I must say, my parents did start us out on the right track when it came to fruits and vegetables. Fresh was best, they preached. Thank you, Momma and Daddy.

After we loaded up on fruits and veggies, we headed back to the city and downtown to the meat market. Paula, Michael, and I went inside to help Momma shop for the freshly ground chuck beef and pork shoulder, the bacon on a slab to be cut into the thickness we liked, and all the other meats for the week, including liver, which kids usually can't stand, but I loved.

After we stocked up on beef and pork, the next stop was the chicken market on Quincy Avenue. Daddy picked out the live chickens. We kids watched as the birds got their necks wrung, their heads chopped off, and then ran around the yard until they fell over dead. Whenever a grown-up shouted to us kids, "Sit down! Be still! You all are running around like chickens with their heads chopped off," I sat down because the visual was too much.

After the chicken market, it was on to the other stores to pick up staples, from cornmeal and flour to lard and sugar -- and boring stuff like bleach, steel-wool pads, napkins, deodorant, and toilet paper.

It was a regular thing that not all the food made it home intact. We chomped into apples, we nibbled grapes. When Momma went solo into the grocery store for the staples, back in the car Daddy sometimes let the oldest kids share bottles of Carling's Black Label. Marcia and Brenda could only have sips. Between swigs of beer, we would munch on Limburger cheese and bologna off the roll, just like the old men did, crunching green onions on the side. When Momma opened the car door, she'd ball up her face like she was about to throw up through her nose. "Why do you have my kids stinking like this? This is disgusting, Joseph!" My father truly believed that beer now and then would not hurt us. Plus, I think he liked to watch our mother's reaction when she opened up the car door and almost passed out from the beer-bologna-cheese-onion funk emanating from her six kids and fat hubby. As Momma scowled, we all fell over with laughter. A lot of our laughter revolved around food. But the worst wallop I ever got from my father also had to do with food.

I was about seven and saw my father with donuts in the living room. It was a Saturday, but for some reason my father hadn't made dozens and dozens of donuts. "Oh, Daddy, can I have a donut?"

"I don't have enough for the rest of the children," he told me. "You can have this donut, but only if you eat it right here." He marked the spot with his finger.

My sibs were outside playing; Momma was tooling around in the kitchen. It was just my daddy and me in the living room. I nibbled up my donut and tucked the last chunk of it in my bottom lip when he wasn't looking. "Daddy, I'm finished. Can I go outside now?" Even I was shocked and amazed that I could speak clearly with food in my mouth.

As soon as I got on the other side of our front door, I picked that last piece of donut out of my lip and raced to taunt Paula, Michael, and Fred. "Na na na na na! Look what my daddy gave me! I got some donut, and you can't have none!"

They ran into the house with such speed that in what seemed like a second, I heard, "You little big-mouthed heifer, come here right now!" When I got within a foot of Daddy:

"Didn't I tell you not to -- "

Wham! His backhand sent me sailing through the living room and into the kitchen where Momma was cooking. A wall stopped my flight. Calmly, Momma turned her head. She looked at me, then at Daddy. "Oh, your ass going to jail for hitting my baby like that," she said. She scooped me up in her arms, rushed downstairs to the car, and laid me down in the backseat. "Baby, don't move. Be still." She placed a towel over my face. We were in an emergency room within two minutes.

I looked like I had gone a few rounds with Sonny Liston. I couldn't believe my father had done this to me -- my daddy, who told me repeatedly how much he loved me and who said he would do anything for me, even die for me.

When Momma and I returned home from the hospital, Daddy showed no remorse. "Maybe you'll learn not to tattle now." That's all he said to me. As for Momma, she was not one for idle threats. She had Daddy arrested. He spent maybe three days in the slammer.

I was nine when my father was arrested again, in the winter of 1963. This time it was for drunk driving, and this time he took sick while in jail. Nobody told us children what was wrong with him. All we knew was that he had been moved to the infirmary. The next thing we heard, Daddy's coming home! February 15 was the magic date.

We supercleaned and spruced up the house for his homecoming. I'm sure a big meal was planned, but I have no memory of what it was. But I do remember my sisters Marcia and Brenda, ages five and four, sitting on the bedroom floor, rolling a ball back and forth, and having the strangest conversation.

"Daddy sleepin' in his suit," said Brenda.

"I know Momma gonna be mad he sleepin' in his good suit," said Marcia. "Why won't he wake up?" The two kept rolling the ball back and forth.

Daddy never came home. A few days after his proposed release date, he lay in a casket at the House of Wills, "sleepin'" in his good blue suit, white shirt, and red tie. My father had proudly served in the army during the Korean War, and so they buried him in America's colors.

Laughter was the cause of our dad's demise, we were told. He was telling another guy in the infirmary a joke, and after Daddy hit the punch line he laughed, laughed, laughed -- fell over dead from laughing so hard. So the story went.

Nobody ever said, maybe he drank too hard. Johnnie Walker Red Label was his standard.

Nobody said, maybe he answered way too much that midget bellhop's "Call for Philip Morris!" in the commercial. My father smoked at least two packs of cigarettes a day.

Nobody said that if my six-foot-tall father had not eaten so much of his homemade sausage and donuts and Momma's chitlins and lard-fried fish, maybe he would not have ended up weighing over three hundred pounds and dead at thirty-one. It was not until years later that it was pieced together why I lost my father at an early age: a diabetes-induced heart attack. I also did not know when he died that his mother was a diabetic.

Because nobody remarked on Daddy's lifestyle, nobody thought that we should change ours. Like Daddy, Momma had smoked for years, and she kept doing so after he died. She also kept up her love affair with that riding-boot-shod, red-jacketed, monocled, striding Johnnie Walker and her Dewar's.

On the food front, we continued to eat plenty. Yet none of us was really overweight. Momma, five-foot-eight, weighed about 160 pounds. No Twiggy, but also no whale. Her children were not fat. My sister Paula was taller and larger than most kids her age, but she was not fat; she was large. I was more than not fat. I was stick skinny.

I was mocked, ridiculed, even shunned for being so thin. Everyone said I was abnormally bony. When I was about five or so, my sister Paula often told me that Momma had found me on the steps of St. Paul's Church while on her way to the L&B grocery store. She had brought me home, and Daddy let her keep me. Paula always said that I was not a real member of the family. That's why I was so bony and homely, she said.

Later, the boys in the neighborhood were the cruelest, including the one I had a crush on for the longest time. He called me Olive Oyl. He said hateful things to me like, "If you turn sideways, I could punch you in the head and thread your bony face like a needle." He "serenaded" me with "Bony Moronie, she's as skinny as a stick of macaroni." How I hated that song! When Joe Tex had that hit "Skinny Legs and All," oh, brother. "You've got your own theme song," the boys teased.

In my world, "healthy" didn't mean unclogged arteries and no high blood pressure. Healthy meant "meat on your bones." I venture to guess that at least 40 percent of the adults in my neighborhood were overweight if not obese. People equated skinny with sick. They thought I was sick. I thought I was sick. I did not want to be sick or die from starvation like Uncle Fred. And it was my brother Fred who was the worst when it came to the teasing I got at home. He did like to ball himself up, roll across the floor, and use me as his human bowling pin.

I was also teased for taking my time at the table. I naturally ate the way I now know we are supposed to: taking small bites, chewing well, taking at least twenty minutes to eat a meal: all the better for your digestion and for enjoying the food, allowing the flavors to mingle and the aromas to mesh. But wolfing down supersized platefuls of food was my family's tradition -- a tradition guaranteed to have you eating more than you should. The healthy approach is to allow your stomach time to signal "full," not gulp down the food until you feel like you're about to burst. Until I got the hang of speeding up my eating, I often lost out. One sibling or another snatched food off my plate, thinking I did not like the meal. I was rarely a "good clean-plate girl." That's what they called you when you ate all the food on your plate: a good clean-plate girl or boy.

One of our family rites of passage that revolved around food was birthdays. Twelve was the magic age when we received the privilege of choosing the dinner menu for our birthdays. As Paula's twelfth birthday approached, she put in for her favorite: beef Stroganoff, made with lots of sour cream and loads of beef. Mine was porterhouse steak, baked potato, salad, fresh lemonade or iced tea, and German chocolate cake. For another sibling, it was spaghetti with shrimp. And always there would be an "international" dessert. That became my department when I was twelve. After I saw how fabulous my German chocolate cake was, with frosting made from scratch -- like the rest of the cake -- I was too ready to be Little Miss Pastry Chef.

I soon began to spread my culinary wings and try my hand at some international main dishes. I was on it! I would look through our set of encyclopedias and get inspired by a region of the world, then plan a meal. I found Asian culture especially intriguing. That's how I came to make Peking duck as part of the specialty menu for one Thanksgiving dinner. Both ducks were great, with a nice, crispy orange glaze. But I found out I needed to have had as many ducks as there were in Peking to satisfy my family. "Yeah, it's good, but it wasn't enough," was the response I got. No one had a clue that if you are going to eat something really rich or greasy -- and duck is both, as is fried anything, pastries, and so much more -- you should take care to eat only a small amount. Had someone tried to introduce my family to the notion of portion control, they would have viewed it as punishment and maybe slapped the messenger, too.

After my father died, food loomed even larger in our lives. Letting a kid try her hand at duck is just one example. I have often wondered if my mother was overcompensating for our being fatherless and her increased absence because she had to work more. She worked more overtime at the post office, dropped the job at the hospital, and picked up a gig at a bar. (My mother did not change jobs; she changed professions. She later went to college and became a schoolteacher, then, after more study, a social worker.)

After Daddy died, Momma's schedule was wicked. After her day job, she came home to eat and change her clothes, then head to the bar, where she worked until closing. She got home about three in the morning, slept until seven, and started again the next day. We would do well if we saw her awake for more than a few minutes during the week. Grocery shopping changed as a result of her working more. There was a rise in frozen and canned foods. Whereas before, we ate homemade noodles and spaghetti, after Daddy passed, Momma started buying boxed pastas. The boxed spaghetti looked so strange to us, with all the strands so even and the same length. Momma also switched from lard to vegetable shortening. She said that vegetable shortening was better for us. Plus, it made better cookies. As I recall, the only healthy change Momma made was to switch from white bread to wheat.

When an aunt and uncle were not living with us, Paula became our chief cook. She loved food fried, barbecued, fried, and fried. Chicken, fish, potatoes, steak -- whatever. The girl could throw down.

And I was getting into the habit of wolfing down my food.

Copyright © 2006 by Mother Love

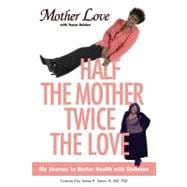

Excerpted from Half the Mother, Twice the Love: My Journey to Better Health with Diabetes by Mother Love

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.