Approaching from a distance, hand in hand like lovers, the tall blonde and the old gentleman both called out to him – Brecht! He turned towards them and waved. The Californian sun glinted from his glasses like the sword of Zorro. It was early morning. Heat and the scent of jasmine hung loosely all about the market-place. Sunlight played upon the unreal splendour of the fruit and vegetables. Not quite real. Some people claimed the produce of this country lacked character, it always looked much more promising, bigger, brighter, than it tasted. Especially apples. They complained that there were certain things – gooseberries, for instance – which you could not get at all. Asparagus only came in cans. And who had been able to buy chanterelles since they’d left Europe? On this day in the summer of 1944, just before the German generals’ attempt on Hitler’s life, the news had sped like wildfire through the community of European exiles in Los Angeles that a farmer from the north was selling berries at the market. Not just strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, there was also a small supply of gooseberries. At the head of a line of people anxiously waiting to be served, Bertolt Brecht chewed on his El Capitán Corona. Fond of sayings and slogans, he proclaimed that the early bird catches the vorm, and money talks, and proceeded to buy up all the golden berries. Oh yes, they were ripe enough to eat. Striding across the plaza towards Nelly and Heinrich, he stopped here and there to divide the loot, handing Gänsebeeren, as he jokingly translated from the English, to friends who had missed out.–Ah, here comes the man who loves gooseberries, someone said in a heavy accent, referring to one of Chekhov’s stories, casually, as if Russian classics were still common currency, as if Brecht had just crossed Berlin’s Savignyplatz and was offering summer berries from a cone-shaped paper bag. Finally he scooped a great mound of amber fruit into Nelly’s basket. He gave them each, Heinrich and Nelly, a translucent gem to taste.–One for Adam and one for Eve, he chuckled. The proof of the pudding. And crushing a berry against his own palate like an oyster, announced triumphantly that it was delicious, the real thing, not a hybrid, and that he was no gooseberry fool.

It could have happened.

It had to happen.

It happened earlier. Later.

Nearer. Farther off.

It happened, but not to you.

WISLAWA SZYMBORSKA, ‘COULD HAVE’

Several months later, on Sunday 17 December 1944, at home at 301 South Swall Drive, Los Angeles, in the not yet broken darkness before dawn, the outline of a bowl of fruit on the windowsill, its curves – a hand of bananas Nelly had bought earlier in the week, grapes, some pears – reminded Heinrich of Brecht’s generosity and of their animated exchange that day at the market, when they’d all had new information about friends in trouble, jailed, people killed, and shocking rumours of the progress of the war. Oh the terrible disgrace! They’d switched between languages, Stachelbeeren, Stacheldraht, Stacheln, barbs.–Barbarians! Brecht had exclaimed. But that moment, which Heinrich tried to conjure up, now faded.

It left nothing before his eyes but a silhouette of fruit backlit by a gauze of curtains, grey on grey. He was a very old man shrinking from the night, from this terrible night, the worst night of his life.

He was no longer sobbing uncontrollably. He felt numb. Unable to focus. Did he doze? Briefly? Perhaps he was dying? His only physical sensation came from the bridge of his spectacles pressing on his nose. He made himself take them off, and rubbed his eyes. Did he then recall or did he dream? That when they were children his brother had once worn a peg on his nose for a whole day, until a blockage in the plumbing was fixed and the stench the household had to endure was gone.

Heinrich sat very still inside the folds of his suit. Inside the immaculate whiteness of his long-sleeved shirt. His wife had washed it, hung it out, brought it in, ironed it as he watched her through the open door, and placed it on a hanger, smoothing it with the flat of her hand, tugging each cuff into shape. This image and the thought of her absence was too much to bear. He was crushed with grief. He sat deep inside the maculations of his own soft skin and felt minuscule. Like a grain of sand. His mind searched for a place to go, where it could escape.

In Lübeck. In summer. In the garden. In the scented air. Where it was warm and still. A red dragonfly–Sympetrum vulgatum, the vagrant darter, how strange to remember it – hovered over the fountain like a hawk. Dragonflies fed on mosquitoes; mated in the air; this one settled for a moment on the leaf-blade of a stand of purple irises. Blackcurrant and prickly gooseberry bushes grew against the garden wall. He sat in the shade of the walnut tree. From an open door someone called his name.–Children, how far did we get with this? he heard his mother ask.

A change in the weather. A wind came up, and suddenly clouds like great grey waves were being swept along. The boy looked up, following their crazy script. Just then a grain blew into his eye and he rubbed the irritation with his fist until the billowing sheet of sky that he’d been watching flashed red from too much rubbing, and his eye burned with pain. He took up his pencils, blindly, and the sketches he’d made. With one lid shut, the other squinting sympathetically, he felt his way along the wall until he reached the door.

The old man did not want to enter. He knew that there was no going back. For one thing, this house at Beckergrube 52 no longer existed, it had been destroyed during the British raid in 1942.

Lübeck, a member of the once significant Hanseatic league of Baltic ports, lies on a low-crested island between the rivers Waken-itz and Trave. Even in the long decline since its peak of power in the fourteenth century, with its trademark late-Gothic gateway, the Holstentor, and the towers of St Aegedien, St Jakobi, St Katharinen, St Marien, St Petri, and the Dom, rising above step-gabled merchant-houses that line narrow streets and foreshores, the town always retained the demeanour of an independent trading centre. During the night of 28–29 March 1942, by the light of a nearly full moon, deemed excellent visibility, more than half of Lübeck’s buildings were destroyed and hundreds of people killed and injured; 234 aircraft had split into three waves of attack to drop more than 400 tons of bombs. In retaliation, it is said, the Germans opened a Baedeker tourist guide to England, selected several sites of historic significance, and bombed Bath, Exeter, Canterbury, York and Norwich.

But of course, innocent of what the old man knew, the boy had already gone into the house, there was no stopping him. He was splashing his face with water, telling his sisters no, no, that he hadn’t been crying, that it was just a bit of dirt. And so the old man followed his childhood self, unseen.

–How far did we get? their mother asked again. On sofas and chairs they sat in an attentive circle, while she opened a volume, resting it on the lid of her desk. To read to them, she often stood up, and so it almost seemed like a sermon in church, or a lesson in school. It might have been in the early summer of 1886, when he, Heinrich, was aged fifteen, Thomas (whom they called Tommy) was eleven, Julia (called Lula) was nine, and Carla, sitting close to her eldest brother, was only four years old. Always inclined to theatrical pranks and gestures, they had picked flowers that morning and had assembled for the reading, with Carla wearing an extravagant crown of pansies. Tommy had plaited it, Lula had pinned it to her sister’s curls. Now they waited in mischievous silence, until their mother looked up from leafing through the book and broke into a smile.–Ah yes, she said. Here we are…she wore a little wreath of pansies.

Then she continued…and there were more pansies on the black ribbon winding through the white lace at her waist…They were spellbound by the scene of Kitty, Anna and Vronsky at the ball, by the quadrilles, waltzes and mazurkas. But some minutes into the reading they noticed, one by one, the intense concentration etched on Carla’s petalled brow. She had folded one leg up against her chest, her slender arms encircling her knee. This was how she always sat, in her own embrace. And for a few seconds more, she held her pose, deepened her frown, delighted in her audience, before she too, not exactly knowing what was funny, burst out laughing.

An actress, Heinrich thought. Years later, this is how he would begin his tribute to his sister…She was an actress.

As far back as each of them could remember, their mother had read to them. Folktales, Mörike’s Peregrina poems, Goethe, E.T.A. Hoffmann’s sinister stories that made their hair stand on end, or Theodor Storm’s sentimental ones awash with wind, sand, sea and mist, where the moon swam from its cloud cover, and where in summer on wooden benches in the shade of linden trees young boys listened to the chronicles of old men’s lives. As soon as she discovered new books for herself, thrilled especially by heroines who were themselves readers of the same novels she had lined up on her shelves, she read selections to her children. They were captivated as much by their mother’s dramatic ingenuity – she could be a haughty princess, or one of Fritz Reuter’s roughest peasants speaking dialect – as by the language, crisp or languorous, the spin or tease of verse, the ever-new suspense of stories they’d heard a dozen times before.

Tommy wanted to know how characters clung to life. He held a toy soldier tightly in his hand. To live, to live on and not die, like Frederick the Great who had inspired his troops to persevere. One day, the novelist Thomas Mann would write that all the heroism lies in enduring, in willing to live and not die. At the end of the reading hour he often became aware that his mouth had stayed a little open and his eyes were half closed, that the rhythm of his mother’s voice echoed in the warm, gentle pulsing of his blood as it coursed through his body; there was a wavelike rushing in his ears.

Even more memorable than these sessions in the library were the bedtime stories Julia told her children, who half reclined on pillows before sleep, or sat on the floor of her room as she dressed to go out. Tommy fastened her pearls. Heinrich sketched. For herself Lula dreamed of ruffled dresses and festivities. And Carla played with a collection of fans, fluffing their feathers or tracing their painted landscapes with her finger. All the while, intrigued by the romance of their family heritage, they listened closely to their mother’s childhood reminiscences.

The fourth child of Maria da Silva, of Portuguese-Brazilian descent, and Johann Ludwig Hermann Bruhns, a North German coffee and sugar merchant, Julia Mann was born Julia da Silva Bruhns in 1851, while her parents were en route between the Brazilian coastal towns of Angra dos Reis and Paraty. She was not yet five when her mother died in childbirth in 1856, seven when she, her sister, brothers and father made the two-month journey to Lübeck, where the girls, under the guardianship of their widowed German grandmother, were to be educated. Obliged to attend to his business in Brazil, her father bid her a sad farewell and returned to South America with his sons. Through death she had lost her beloved mother, and then through distance that seemed as sundering as death, father, brothers, home and language. Julia mourned as only a child mourns, with an unwavering fidelity to all she’d lost.

Later she re-created for her children what she always longed for. She coaxed their limber imaginations to the doorways, windows and verandas of her childhood home, the Fazenda Boa Vista, to look in one direction across the Bay of Paraty, in the other, along a dense wall of forest. She asked them to choose which way to go, towards the sea or jungle, and so to select their favourite stories.

To convey the allure of the sea, she would tell them she was fishing for words, prompting her audience to call out colours – sapphire, turquoise, emerald, ink – with which to paint the water, where it lapped onto pale sand, where they waded, swam, then deeper, where they rowed. Shells and rocks, she incanted, ships, islands, the horizon. Silver at dawn, copper at dusk. Within this glistening shorescape, she unfurled a series of adventures made even more incredible by the occasional appearance of a powerful sea-goddess or a temperamental, shape-changing serpent.

Their mother said that when she was very young she had heard the beat of the green heart of the jungle. Monkeys, parrots, toucans, hummingbirds, orchids, flowering climbers, glass-winged insects, with every retelling the bounty was augmented. Each of the children entered their mother’s trancelike pact of remembrance, and claimed an affinity with this closely woven tapestry of sound and scent and light. Lula and Tommy thought that their darker colouring most closely matched their mother’s, and Tommy convinced himself of a special mutuality, that certain exotic racial characteristics in his external appearance had come to him from her. They were unaware that in order to enhance her own romantic image of herself, she dyed her hair. Many years later, writing Death in Venice, he might still have wiped his brow with his pocket handkerchief when imagining – on his hero’s behalf – crouching tigers, creeping tendrils, rising sap, and a hairy palm-trunk thrusting upwards from rank jungles of fern, from among thick fleshy plants in exuberant flower…

Carla was sure that she closed her eyelids, fringed with long black lashes, just as her mother did, slowly, to be transported to faraway places and fabled lives, daughter like mother.

Heinrich had no need for special claims. When he was born, 27 March 1871 (the year Germany became a nation), named Luiz Heinrich, nicknamed Heine, his mother was barely out of her teens, and for four years he was her only child. He was the first of all his siblings to hear her laugh out loud like a schoolgirl, or whisper conspiringly, play Chopin, or sing Lieder, sweetly, to herself. The first to learn that she sometimes disappeared into a terrible tumescence…of what, he did not know…of melancholy…and that his childish kisses and embraces made her sigh, but that he could not console her. In equal portions, their relationship combined intimacy and distance. I sit in front of her desk, playing with a small bronze box, its lilac lining effusing a magical scent. In this box, or perhaps in another, he found feathers, shells, tiny rings made from the tailtip of an armadillo, a little black ragdoll she called the negrinho, and most curiously of all, a leathery hand-sized purse which was the large dried flower of the golden chalice vine, Solandra maxima. A neat circle of holes pierced near its mouth was threaded through with faded velvet ribbon; it was full of clinking foreign coins.

Some objects are the shape of thoughts. Some thoughts illuminate the dark, like swamp lights, constellations, lines of narrative. In Los Angeles, in the dead eye of night, without conscious effort, Heinrich Mann sketched his childhood. He was a boy stretched out in a summer garden, daydreaming, picturing the adult world just outside his reach. A woman who resembled his mother turned away from a man, an officer with a sword at his side. Who was this man? Was she rejecting him, or flirting? Was it a game? Water spurted from a fountain, unambiguously. There was a walled garden, a house, and inside the house, a baby in a cradle. From courtship to consummation and conception, to birth, his own birth, or one of his siblings’, in one round scene.

The old man remembered how as a boy he had once watched his parents as they dressed for a party, a masquerade. My father is a foreign officer, with a powdered wig and sword, I am immensely proud of him. As the queen of hearts Mama flatters him more than ever. His father – Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann, called Henry – always wore softly textured suits, and a small flower in his lapel. He was a grain merchant, head of the family firm, and a senator; a pillar of society with many civic responsibilities. He made, lost and regained fortunes. He was a man, Heinrich later said, who was unfamiliar with the idea of creative genius outside business hours, and who believed that his experience and status would one day pass to his eldest son.

Although the boy liked to read the newspaper across his father’s shoulder, and to accompany him on walks through town or rides into the countryside, he was a dreamer. He was too impressionable. When he watched marionette performances, or when his mother read him Theodor Storm’s story about a puppet theatre, Pole Poppenspäler, another world entered his imagination, and like its hero, a single glance at the stage sufficed to carry him a thousand years back in time. When his parents took him to a real theatre, he could not see the phantom line between life and art, and during the performance, deeply enchanted, he made a racket calling out warnings to his favourite actor about to be ambushed on the stage, and had to be taken home.

Germans love puppets and anarchic fools. In the form of man-children, savants, jovial tramps, blockheads, they are what you grow into if you don’t conform, outsiders that embody obscenity, contempt, ridicule, rebellion, transgression. Known as Till Eulenspiegel, Münchhausen, Kasperle, Hans Wurst. Goethe was inspired by the figure of Faust when as a child, season after season, he watched the folk-character of the same name, comical, grotesque, in the popular routine of bantering and bargaining with his Punch-like sidekick. His contemporary Heinrich von Kleist found in the marionettes’ mechanical flow of movement a superior form of dance, unachievable by humans shackled by physical and existential heaviness from the double burden of gravity and self-consciousness. The more Romantic the writer, the greater the conviction that the marionette replicates not life but its essence, its signature, that within their wooden core the dolls carry a spark of soul. No matter that the glint from the puppets’ dark pupils can be explained as light catching the metal head of a tiny nail, of the kind that cobblers use to fasten together the upper and lower leathers of a shoe. A favourite in the Mann household was Hoffmann’s tale Der Sandmann. The story’s protagonist Nathanaël was the victim of his own imagination. As a child he was overcome with a terror of the fabled Sandman, who prowls at night to steal the eyes of wakeful children. As a young man he suffered from his misplaced and unrequited love for a doll-like creature. Like myriads of eyes, dark meanings lurk in every corner of his life and their burning gaze drives him to madness and death.

Heinrich and Tommy, Lula and Carla, and later their youngest brother Viktor played with marionettes at home, and with model-theatres for which the figures and scenery came as sheets of paper cut-outs that had to be assembled. The conventional Papiertheater repertoire included operas like Lohengrin and The Magic Flute and plays by Shakespeare, Goethe, Schiller and Kleist, which the children received as Christmas gifts. They were also inspired to create their own plays. The writing of scripts, the painting of backdrops, the drawing and cutting-out and colouring-in of figures, the placing of them on stands, the invention of sound effects – dried peas or lentils in a carton for rain, or for applause – followed by rehearsals, and family performances, kept them happily occupied throughout the long Northern winters.

Inside the mighty church of St Marien, not far from their home, a thirty-metre-long eighteenth-century copy of a fifteenth-century fresco of the Dance of Death impressed all who saw it. Created in 1463–after the plague had ravaged Lübeck’s population several times – the twenty-four life-sized representatives of social rank, from pope to empress, duke, doctor, merchant, maiden and newborn child, are invited by a troupe of black skeletons to join hands in a dance, a farandole. The Black Death as punishment for earthly sins. But who leads in this danse macabre? It is the worldly dancers, with their flourishes of colour and choreography, who are keeping time, who are the death-defying custodians of life and energy.

Nonetheless Thomas Mann later claimed that he and his brother were strongly influenced by the shadowy atmosphere of Lübeck, where twisting Gothic alleys and hidden corners seemed to be haunted by something very old and pale, emotionally deformed, spiritually diseased, a remnant of the hysteria of medieval times. He said Lübeck was the city of The Dance of Death. Hans Christian Andersen, who visited St Marien in 1831, thought he detected ironic smiles on the skeletons’ faces, and was moved to write a story about a boy called Christian who asked for paper reproductions of figures from the Dance of Death to play with. Most likely, for the Mann children, those images in all their ambiguity would have provided rich material for theatrical productions and night terrors. The church fresco was destroyed in the bombing of 1942.

When Heinrich painted scenery for family performances, he thought that one day he’d become an artist. The puppet theatre also nurtured Thomas’s fantasies. Here he served his apprenticeship for the craft of writing and gave himself a foretaste of the hot glow of success. In one of his earliest stories, ‘Der Bajazzo’ (‘The Dilettante’), he transposed a pastime normally shared with his siblings, into one of intense solitude, as if he’d been an only child. The narrator describes his favourite childhood activity, of creating, directing, acting out an opera alone behind the locked door of his room, where he plays every part, from librettist, to usher, to members of the audience conversing before the show. He even cuts a hole in the paper-curtain for his paper-actors to see if the performance is well attended, which of course it is. He tries to conduct the orchestra, sing the different voices, and play various instruments, all at once, there is great applause, and as concert master he takes a low bow to thank the players and the audience. At this point he could only imagine a full house, but the large numbers of people, sometimes several thousand, that later attended his readings and lectures would count among his greatest adult pleasures.

Their mother’s desk did not have a lock, and every morning before going to school Heinrich placed his small violin inside, high enough for Tommy not to reach it. It should have been a safe place. He later wrote that the instrument was his joy, or the promise of joy one needed to look forward to each day. But when he returned he often found that it had been played, or rather played with, since sometimes it was damaged, with loose or broken strings and scratches. He wondered who helped his brother take it out and then replace it. When this happened once too often, Heinrich raged. His behaviour was met with dark looks and sharp words from his mother. One day he came home to find his violin in pieces. He cried. You see, his mother said, it no longer matters if it was yours alone or if it belonged to both of you, now that it’s broken. Complex reasoning for a young boy to comprehend.

The brothers were tied by bonds of love and jealousy. There were fallings-out, short and long periods of not speaking to each other, followed by peace. Tidal forces of affection. During one of the family’s summer holidays in Travemünde, a seaside resort fifteen kilometres from Lübeck, to cut the ice, Heinrich raced Tommy to the shore and deliberately fell over in the sand to let his brother win. Then they dipped their toes into the blue-green water – measured in degrees of coldness, even on the hottest day – and daring one another, they both plunged into the waves.

Two hundred fifty rivers drain into the glacial basin of the Baltic Sea; as the largest volume of brackish – in some parts almost fresh – water on the planet, it contains only about a quarter of the salt of oceans. It was once a lake and has been a sea for a scant 7, 000 years; now it is related to the North Sea, and distantly, to the North Atlantic, via narrow straits. Sudden wind changes and violent storms make it hazardous for ships; on its bed there are more rotting, rusting wrecks than in any other sea on Earth. Heinrich told his younger brother, as they dived into the viridescent waves, about a marine landscape of ships’ hulls, broken masts, treasure chests and cannonballs, crusted with shells, flagged with fluorescent algae. He said that the Baltic was a cemetery. That swimming further out, they must be careful not to touch the bottom with their feet, for fear of kicking up old bones; that the water of the Baltic tastes like blood.

In Los Angeles, in the not yet broken darkness before dawn, Heinrich cast pencil markings across a new page of his sketchbook: 1886, he calculated, May or June, when their mother began to read Anna Karenina to them, for soon afterwards they were on holiday, and the book, unfinished, had been left at home.

Travemünde in July and August was a place of milk-washed skies, sand like silk against the skin, shells picked up and left randomly on windowsills and gateposts. Everyone rose early and retired late; with a Nordic thirst for light and warmth, accumulated over too many months of winter, they lavished themselves with sun. At the water’s edge was the familiar line-up of bathing machines which one entered clothed and exited by a short ladder, temporarily amphibian, for health from seawater and sea air. From the promenade, and from a maze of manicured gardens, with the crunch of pebbles underfoot, came bursts of laughter and sounds of calling to acquaintances, in a great variety of dialects and languages. Holidaymakers wearing mostly white, men with straw hats, women twirling parasols, strolled, or gathered with contagious leisure, against the backdrop of the hardly incongruous row of picturesque Swiss chalets, or the Musiktempel, or the Kurhaus, where one sipped salt water. On the beach children chased raucous seagulls, and with Lilliputian spades built forts and castles; with their bare hands they dug wet sand, urgently, to make channels and as the water rushed in and out, and the walls threatened to collapse, they hurried to secure them; if someone wilfully destroyed these masterworks, there were slaps, kicks, howls, tears.

A youth carrying a book might slink towards the dunes to read or daydream, unsure of his status in society, while others of his age rehearsed the arts of courtship in every little way. Two or three young people walked in the direction of the lighthouse and the Brodtener Steilufer, a cliff from which great chunks, trees even, sometimes fell into the sea; at its base was a narrow strip of sand, a renowned treasure trail for fossil hunters, leading between Travemünde and the fishing village of Niendorf.

Along slowly darkening paths some who stayed out late followed the rituals of glow-worms – wingless female beetles, Lampyris noctiluca–that lit up their bodies to attract the unilluminated flying males.

Like many others, the Manns probably hired an open carriage for excursions to villages further along the coast, Niendorf, Timmendorf, Scharbeutz, where they would eat freshly smoked fish for lunch, herring, sprats, or eel. They stopped to buy berries from a farmer’s stall, and the old coachman took a nap while they picked great bunches of blue lupins that grew beside the road, and strawflowers from a white-gold carpet covering the dunes. As they headed back to Travemünde for dinner, fields on one side, sea on the other, Lula coughed from the dust kicked up by the horses, and Heinrich noticed that Carla was almost asleep against his chest, that Tommy was sunburnt.

Light and shade flickered hypnotically as the carriage rolled through a forest of beech trees. The coachman told stories. Not only amber washed up on these shores, he said, but people too, the living and the dead. He recounted the terrible storms he’d experienced in his lifetime. The worst by far were the winds that caused the great flood of November 1872, when it seemed as if, in the black of night, the sea would altogether claim the land. Trees bent like straw, buildings were destroyed, others filled with sand, people and animals drowned, those who had managed to climb onto roofs felt the walls collapse below and were set adrift. As the water subsided, survivors were found in treetops and boats on meadows far from the shore.

Going further back in time, the coachman thought it was the summer of 1837, he was a young man then, courting the innkeeper’s daughter, and he remembered that travellers on their way by ship to other Baltic ports had to wait for the wild weather to abate before continuing their journeys. The wind was so powerful that a beehive was tossed high into the air and carried to an island with its swarm intact. For days the inn was full of restless people, pacing, smoking, drinking; not a rowdy bunch at first, but they grew irritable as the conditions worsened. He remembered one man going to Riga who was increasingly impatient with the delay, intolerant of the crowded space, red with anger; how the volume of his voice rose from his chest, producing rapid streams of curses; how he slammed the wooden benches with his fist. To calm him, the innkeeper showed him a book which absorbed the man so completely, he was seen musing, making notes, tapping rhythms on the table. When the storm passed and it was time to continue their journey, his wife had trouble rousing him from his concentration. The fellow’s name, the coachman revealed as he pulled up at the hotel entrance, was Wagner.

And the book the innkeeper had brought him was Till Eulenspiegel, which he’d immediately thought would be a perfect subject for a quintessentially German comic opera. Richard and Minna Wagner were going to Riga, where he was to take up the position of musical director at the German Theatre. The Wagners’ return journey in 1839, with their Newfoundland dog, was even more eventful. Minna was pregnant, and having lived beyond their means in Riga, they were travelling in a great hurry across borders, without visas, to escape their creditors. At one point their coach overturned, and as if the trickster Eulenspiegel himself was at work, Wagner landed in a pile of dung. Man, woman and dog crawled through high grass to reach the dinghy that would take them to their ship. Minna later found she had miscarried. They expected to be in London in a week, but the trip took almost a month. Tempestuous weather blew the small merchant vessel far off course; it was driven onto rocks that tore off its figurehead, and the sailors, familiar with the legend of the fleeing Dutchman, suspected that the Wagners might be the harbingers of great misfortune. Wagner’s opera based on this experience premiered in 1843. It was a great success.

In early September 1886 the Manns arrived back in Lübeck, bright-eyed and tanned, with bunches of everlasting daisies, Im-mortellen, rustling on the girls’ wrists and bursting from their hatbands.

Heinrich was a reader. When he was very young, he was given a volume of enticing tales and images that danced through his dreams at night; this was his first literary love. But he’d left the book at his grandmother’s place, and somehow it disappeared before it could be truly savoured. Over the years I asked for and was given many other books, but never that one…Much later, when it was time to choose books for my daughter, I remembered the one I’d lost. Curiously, I always avoided buying that one for her. Little did he know then that more than once, going into exile, he would have to abandon his entire library. There’s a photo of him aged about fourteen or fifteen, with his fingers firmly placed between the pages of a book, as if, in mid-narrative, he’d only granted a few moments of his time to the photographer. It’s easy to imagine that after the family’s return from their holidays, he picked up the page-marked copy of Anna Karenina that had been left behind, and even before unpacking his bags, settled in a corner to continue it.

Around that time in Lübeck the lure of books occupied another child in quite different circumstances. Passing between Beckergrube and the station, the Manns would have known the Lindenplatz pharmacy owned by Siegfried Mühsam. Well-respected in the town, he had been a soldier at the battle of Königgratz, Prussia’s decisive victory over Austria in 1866. He presided over a household at once conservatively Jewish and passionately Prussian; he kept his sword always by his bedside; a cane hung off the back of his chair, ready to strike anyone who slouched at the dining table. He was an example of what psychologists later identified as black or poisonous pedagogy, entrenched in hierarchical cultures like nineteenth-and twentieth-century Germany, where parental love and basic human empathy were suppressed for the sake of a communal order that required discipline and obedience. Mostly it was his son Erich (born 1878) who received corporal punishment, for laziness, and all the misdeeds that an intelligent child, tested by too many rules, might invent. Like Thomas and Heinrich, who later said that their formal education had been a painful experience, in fact, a question of survival, Erich Mühsam attended the Katharineum school, and also like them, he was not a good student. He reacted against the unrelieved strictness of his upbringing by developing a profound hatred of authority, and was expelled for expressing Socialist ideas, although he managed to finish his education elsewhere, and then to study pharmacy. He later became a committed anarchist and writer, and an admiring reader of the work of Heinrich Mann. Of his childhood Mühsam said…They knew that I loved to read books. I never received any presents, and when it was discovered that at night I secretly got out of bed and went to my parents’ bookcase, taking copies of work by Kleist, Goethe, Wieland, Jean Paul, the bookcase was locked and I was deprived even of that one chance to satisfy my deep desire.

It was a time when desire, more arousingly than ever, must have draped its glossy peacock-feathered cloak across this town.

On 15 September 1886, Sigmund and Martha Freud, newly married, travelled from Hamburg to Lübeck, where they stopped for six days, going on to Travemünde for a further two, before their return journey to set up house in Vienna. It seems too sober an itinerary for the honeymoon of the century’s most famous sexual theorist, but years before, Freud had had a drug-induced prophetic dream of trudging forlornly through the countryside, seemingly forever (their long engagement!), eventually coming to a seaport whose medieval-fortress gateway he recognised as Lübeck’s Holstentor, flanked by two sturdy, cone-roofed towers, through which he entered, triumphantly. No mention of the gateway’s iron dentata. And Martha’s perspective was not recorded.

A little later, 1889 or 1890, only a few steps from the Holstentor – via the Puppenbrücke, the bridge of dolls – Lübeck’s Lindenplatz became a site of yearning for Thomas. This neighbourhood was the home of his schoolfriend Armin Martens, the son of a timber merchant. In the novella Tonio Kröger (1903), portraying Martens as Hans Hansen, Tonio (who was Thomas) named what he loved best: the fountain, the old walnut tree, his violin and the sea in the distance, the dreamlike summer sounds of the Baltic Sea. He loved his dark, fiery mother, who played the piano and the violin so enchantingly. And he loved Hans Hansen, and had already suffered a great deal on his account. For it seemed that whoever loves the most is at a disadvantage and must suffer.

Heinrich on the other hand followed his youthful curiosity by visiting the Pension Knoop in a laneway near St Aegidien for his first experience of what he later called normal sensual bliss. Cherished memories… It was also around this time that he was seduced by his cousin, a young woman in her mid-twenties; they had a brief affair.

The difference between the brothers was already set. Thomas would be the one who laboured at his craft. His aesthetic, and his experience of sensuality, lay in attenuation. He would one day tell his wife that his favourite word was Sehnsucht, longing. Heinrich would indulge, engaging all his senses in the art of living, producing his work in hot flushes of creativity. With the result, Thomas thought, that Heinrich’s writing was altogether too excessive, and too often shamelessly erotic.

Travemünde, 1889. An unpredictable blue-grey sky. Through an open window, the heady pungency of pine from scattered stands of trees, orchestral strains from the pavilion in the centre of the town. Encouraged by the anonymous publication of one of his stories in the Lübecker Zeitung, Heinrich spends most of his seaside holiday writing. When two more pieces are accepted for publication, he decides he will become a writer and tells his parents he does not see the use of staying on for his final year of school. A writer! Nothing will persuade him to return to school, and so they try to steer their headstrong eldest son – he was eighteen now – towards an apprenticeship in the book trade. In fact, he would have done anything to cut loose from Lübeck, he would even have become a pimp, he later boasted to a friend.

Those early autumn days when Heinrich knew he would soon be leaving home, he and Carla, now eight, spent the evenings reading together, whatever took their fancy, Heine, Tolstoy. The light fell only on the book. While he read she was mostly silent. She inhaled the words. Her lids closed on certain passages, as if locking an image or idea into herself. Go on, she’d say, go on. She wanted the narrative to flow, no stops, no comments. She said that listening to him, she felt suspended, as from a cloud, watching the world below.

Heinrich left Lübeck on 28 September 1889 for Dresden, where the Manns had relatives, to join a firm of booksellers, von Zahn und Jaensch, Schloss Strasse 24. It was an auspicious time for him, as the very next day one of his stories appeared in Die Eisen Zeitung. The apprenticeship was disappointing from the very beginning. He did not like having to stand all day, keeping accounts, filling out order-forms, sorting books on shelves, or the extended working hours of the Christmas season. It was all immeasurably boring. To his astonishment the worst books, the ones he thought publishers should be ashamed of, were the ones that sold out in just a few hours. In his letters to Carla, he would pun on his employers’ names, joke about Jaensch, send her verses that made up unjaenschlich to rhyme with unmenschlich–inhuman – or compare his experience to schlimme Zahn-Schmerzen, a bad toothache, confessing that every day he felt like pulling out. To make her laugh.

Young would-be writers were setting out in all directions. Franz Kafka in Prague, and David Herbert Lawrence in Nottinghamshire, both started primary school. At this time in Paris, André Gide climbed the stairs to the sixth floor of a house in the rue Monsieur-le-Prince, to a large unfurnished room, and dreamed of placing his writing desk by the window with the entire city spread out below; an event momentous enough to be the first diary entry in what would become his greatest work, his journals. A few months later he wrote, I suffer absurdly from the fact that everybody does not already know what I hope some day to be…that people cannot foretell the work to come just from the look in my eyes. In America the teenage Willa Cather escaped the small town of Red Cloud by moving to Lincoln, where she prepared for university and for a writing career, immersing herself in literature and languages. One of her earliest stories was about a musician who migrated from Bohemia to Nebraska; when his violin broke, he shot himself.

At the bookshop in Dresden, Heinrich had two hours off for lunch to explore the cake shops and tobacconists along Schloss Strasse. Weekends he visited the art gallery, where he disliked Holbein and Dürer and loved Rubens and Van Dyck. To spend the money he’d earned, he went to taverns, dance halls, the opera, ballet, theatre. Brothels at ten marks a night. He was puzzled by his outbreaks of pathological sensuality, as he called it, but thought love must be the highest form of happiness, followed by literary success. He referred to his own attempts at writing as Erguss, ejaculation. He read more than ever, forgettable contemporary writers, as well as Storm, Fontane, Kleist. And Poe, who made his flesh creep. Never quite convinced by the idea of pure fiction, he grappled with the notion of the real as opposed to the believable, and always returned to Heinrich Heine, whom he loved above all others, and with whom he must have identified: his aversion to studies and regular employment, his struggles to prove himself a writer, his urge to travel. Heine’s uncle once remarked that if the stupid boy had learned something worthwhile, he would not have had to write books.

His first Christmas away from home was spent with his r elatives, drinking champagne, eating oysters and roast goose, and no doubt smoking good cigars. From Lübeck he received a box of presents that included opera glasses, stationery, cigarettes and books. A friend sent him some marzipan. He was never homesick.

In 1890 Heinrich completed a novella, Haltlos (To Stop at Nothing); his grandmother died; and that year his youngest brother Viktor was born. His father wrote to tell him that these were serious times, and it was important to secure one’s future through hard work, independence and the circumspection of one’s needs, concerned that if his son did not make an effort to establish himself in a career, opportunities would pass him by. He went home for a few weeks in the summer, and was back in Dresden by the end of July. His parents visited him in November. But the atmosphere at work worsened, and he expected to get fired. He had discovered Nietzsche, the radical content, the dynamic style, urgent, sketchy: he called him the greatest modernist, and asked for Thus Spake Zarathustra for his birthday. By the beginning of April 1891 he had sent a six-page letter of explanation to his father, and had left Dresden and moved to Berlin to work as a volunteer with the publisher Samuel Fischer.

Berlin made a grand impression; he took in everything, cafés, museums, in the evenings he sometimes walked for hours between Potsdamer, Leipziger and Friedrich Strasse, looking for the right woman. He identified his tripartite self as the sensualist who acted on impulse and was running riot, the intellectual who weighed up the consequences of actions and had of late become rather atrophied, and the voyeur who kept a keen literary eye on the other two. Soon Nietzsche’s prophetic voice was getting on his nerves. He explored ideas associated with Symbolism. It seemed his life had only just begun.

His father, who in his letters to his son was always concerned about the tyranny of time, was ill, and Heinrich went home for six weeks in the summer. In August he wrote a poem for his mother’s 40th birthday, recalling the magic of her voice when she read to her children, and thanking her for the great gift of an artistic sensibility that she had passed on to him.

Heinrich was twenty, Thomas was sixteen, when their father died in October 1891, aged fifty-one. He had warned his wife to be strong with her children and if she weakened she should read King Lear. In his will he gave instructions to liquidate the family firm, since neither of his sons was interested in taking it over. He requested that his eldest son’s choice of a literary career should be discouraged. Heinrich later claimed, and perhaps it was only a fantasy, that in his last moments the dying man said he wanted to help him. He interpreted this to mean that his father wanted to help him to become a writer. Perhaps he’d taken this supportive sentiment from the biography of Heinrich Heine, whose father worried how his son could succeed as a poet while Goethe’s name was on everyone’s lips.

The Mann family might then have remembered Hoffmann’s story of the Sandman, with its protagonist Nathanaël declaring that the death of his father was the most terrible moment of his youth. It accorded with Freud’s claim, that a father’s death was the most important event in a man’s life; Freud told a friend that since the time of his own father’s death he had felt thoroughly uprooted. It is well known that for Nietzsche, who was only four years old when his father died, the experience left him deeply unsettled for the rest of his life, as the idea of the father grew large and became pervasive. Wrestling with this ghost, Nietzsche, who was named Friedrich Wilhelm after the paternal figure of the Prussian king with whom he shared a birthday, tapped into what was the era’s greatest challenge: breaking loose. Freud argued that the primary love children feel for parents must necessarily be repressed as they grow up. Otherwise there would be no argument with the past, no independence, no moving forward; but always the force of the original current continues to exist, preserved in the great powerhouse of the unconscious.

Not long after Heinrich returned home that year for what must have been a sorrowful Christmas, he became very ill, suffering a lung haemorrhage. For the next few years he moved between sanatorium-regimes in Berlin (Dr Oppenheim’s), Wiesbaden (Heilanstalt Lindenhof) and the Black Forest, packed in furs and blankets and exposed to the elements on snow-covered balconies in winter, or taking naked sunbaths in the summer, exercising, walking. From autumn 1892 until spring 1893 he was in Lausanne, where he rowed on the lake, returned to Nietzsche, read French literature and made short trips to Geneva (for love) and Montreux (for the casino). Most often he stayed in Riva on Lake Garda at the clinic of Dr von Hartungen that was much frequented by writers and artists, including Nietzsche and Rilke; Kafka was there in 1909 and 1913.

In April 1893, in a state of raptus sexualis, as he called it, there was a jaunt in Paris, followed by a brief final return to Lübeck in May. All the while he pondered over what was healthy, what was sick. He increased his reading, and with great determination to hone his skills, he wrote reviews and short articles, and began work on a novel, In einer Familie (In One Family). For the Manns a chapter of their lives was closing. In the summer of 1893 Julia Mann moved the family south, to Munich. It had all happened in the blink of an eye.

Alone and shivering, for the sun had still not risen, in Los Angeles the old man might also have remembered one winter afternoon in Lübeck in the 1870s. It was already dark. The gas lamps were lit. A distant doorbell to announce someone entering a house. Then the little boy, who is me saw the ice-glazed side street leading down the hill, a perfect place for sliding, and such a great temptation that he tore himself away from the hand holding his. He slid steeply, one foot slightly forward, arms outstretched for balance, he flew with the thrill of speed. Unable to stop, he approached the crossroad, where a woman suddenly stepped out in front of him. She was wrapped-up against the cold, and she carried something under her shawl. They collided, fell, and he heard something shatter, a plate or bowl. But it was dark, he was frightened, and he ran away. Only to be pursued for days and nights by his conscience, as he imagined she was very poor and the dish he broke contained the only food she and her family had to eat that day. To make amends, the boy thought he must give the woman all he owned, his toys, his books.

In the house of exile where the old man sat, a bell rang, followed by the sound of something breaking.

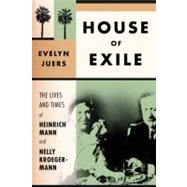

HOUSE OF EXILE Copyright © 2008 by Evelyn Juers

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Approaching from a distance, hand in hand like lovers, the tall blonde and the old gentleman both called out to him – Brecht! He turned towards them and waved. The Californian sun glinted from his glasses like the sword of Zorro. It was early morning. Heat and the scent of jasmine hung loosely all about the market-place. Sunlight played upon the unreal splendour of the fruit and vegetables. Not quite real. Some people claimed the produce of this country lacked character, it always looked much more promising, bigger, brighter, than it tasted. Especially apples. They complained that there were certain things – gooseberries, for instance – which you could not get at all. Asparagus only came in cans. And who had been able to buy chanterelles since they’d left Europe? On this day in the summer of 1944, just before the German generals’ attempt on Hitler’s life, the news had sped like wildfire through the community of European exiles in Los Angeles that a farmer from the north was selling berries at the market. Not just strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, there was also a small supply of gooseberries. At the head of a line of people anxiously waiting to be served, Bertolt Brecht chewed on his El Capitán Corona. Fond of sayings and slogans, he proclaimed that the early bird catches the vorm, and money talks, and proceeded to buy up all the golden berries. Oh yes, they were ripe enough to eat. Striding across the plaza towards Nelly and Heinrich, he stopped here and there to divide the loot, handing Gänsebeeren, as he jokingly translated from the English, to friends who had missed out.–Ah, here comes the man who loves gooseberries, someone said in a heavy accent, referring to one of Chekhov’s stories, casually, as if Russian classics were still common currency, as if Brecht had just crossed Berlin’s Savignyplatz and was offering summer berries from a cone-shaped paper bag. Finally he scooped a great mound of amber fruit into Nelly’s basket. He gave them each, Heinrich and Nelly, a translucent gem to taste.–One for Adam and one for Eve, he chuckled. The proof of the pudding. And crushing a berry against his own palate like an oyster, announced triumphantly that it was delicious, the real thing, not a hybrid, and that he was no gooseberry fool.

It could have happened.

It had to happen.

It happened earlier. Later.

Nearer. Farther off.

It happened, but not to you.

WISLAWA SZYMBORSKA, ‘COULD HAVE’

Several months later, on Sunday 17 December 1944, at home at 301 South Swall Drive, Los Angeles, in the not yet broken darkness before dawn, the outline of a bowl of fruit on the windowsill, its curves – a hand of bananas Nelly had bought earlier in the week, grapes, some pears – reminded Heinrich of Brecht’s generosity and of their animated exchange that day at the market, when they’d all had new information about friends in trouble, jailed, people killed, and shocking rumours of the progress of the war. Oh the terrible disgrace! They’d switched between languages, Stachelbeeren, Stacheldraht, Stacheln, barbs.–Barbarians! Brecht had exclaimed. But that moment, which Heinrich tried to conjure up, now faded.

It left nothing before his eyes but a silhouette of fruit backlit by a gauze of curtains, grey on grey. He was a very old man shrinking from the night, from this terrible night, the worst night of his life.

He was no longer sobbing uncontrollably. He felt numb. Unable to focus. Did he doze? Briefly? Perhaps he was dying? His only physical sensation came from the bridge of his spectacles pressing on his nose. He made himself take them off, and rubbed his eyes. Did he then recall or did he dream? That when they were children his brother had once worn a peg on his nose for a whole day, until a blockage in the plumbing was fixed and the stench the household had to endure was gone.

Heinrich sat very still inside the folds of his suit. Inside the immaculate whiteness of his long-sleeved shirt. His wife had washed it, hung it out, brought it in, ironed it as he watched her through the open door, and placed it on a hanger, smoothing it with the flat of her hand, tugging each cuff into shape. This image and the thought of her absence was too much to bear. He was crushed with grief. He sat deep inside the maculations of his own soft skin and felt minuscule. Like a grain of sand. His mind searched for a place to go, where it could escape.

In Lübeck. In summer. In the garden. In the scented air. Where it was warm and still. A red dragonfly–Sympetrum vulgatum, the vagrant darter, how strange to remember it – hovered over the fountain like a hawk. Dragonflies fed on mosquitoes; mated in the air; this one settled for a moment on the leaf-blade of a stand of purple irises. Blackcurrant and prickly gooseberry bushes grew against the garden wall. He sat in the shade of the walnut tree. From an open door someone called his name.–Children, how far did we get with this? he heard his mother ask.

A change in the weather. A wind came up, and suddenly clouds like great grey waves were being swept along. The boy looked up, following their crazy script. Just then a grain blew into his eye and he rubbed the irritation with his fist until the billowing sheet of sky that he’d been watching flashed red from too much rubbing, and his eye burned with pain. He took up his pencils, blindly, and the sketches he’d made. With one lid shut, the other squinting sympathetically, he felt his way along the wall until he reached the door.

The old man did not want to enter. He knew that there was no going back. For one thing, this house at Beckergrube 52 no longer existed, it had been destroyed during the British raid in 1942.

Lübeck, a member of the once significant Hanseatic league of Baltic ports, lies on a low-crested island between the rivers Waken-itz and Trave. Even in the long decline since its peak of power in the fourteenth century, with its trademark late-Gothic gateway, the Holstentor, and the towers of St Aegedien, St Jakobi, St Katharinen, St Marien, St Petri, and the Dom, rising above step-gabled merchant-houses that line narrow streets and foreshores, the town always retained the demeanour of an independent trading centre. During the night of 28–29 March 1942, by the light of a nearly full moon, deemed excellent visibility, more than half of Lübeck’s buildings were destroyed and hundreds of people killed and injured; 234 aircraft had split into three waves of attack to drop more than 400 tons of bombs. In retaliation, it is said, the Germans opened a Baedeker tourist guide to England, selected several sites of historic significance, and bombed Bath, Exeter, Canterbury, York and Norwich.

But of course, innocent of what the old man knew, the boy had already gone into the house, there was no stopping him. He was splashing his face with water, telling his sisters no, no, that he hadn’t been crying, that it was just a bit of dirt. And so the old man followed his childhood self, unseen.

–How far did we get? their mother asked again. On sofas and chairs they sat in an attentive circle, while she opened a volume, resting it on the lid of her desk. To read to them, she often stood up, and so it almost seemed like a sermon in church, or a lesson in school. It might have been in the early summer of 1886, when he, Heinrich, was aged fifteen, Thomas (whom they called Tommy) was eleven, Julia (called Lula) was nine, and Carla, sitting close to her eldest brother, was only four years old. Always inclined to theatrical pranks and gestures, they had picked flowers that morning and had assembled for the reading, with Carla wearing an extravagant crown of pansies. Tommy had plaited it, Lula had pinned it to her sister’s curls. Now they waited in mischievous silence, until their mother looked up from leafing through the book and broke into a smile.–Ah yes, she said. Here we are…she wore a little wreath of pansies.

Then she continued…and there were more pansies on the black ribbon winding through the white lace at her waist…They were spellbound by the scene of Kitty, Anna and Vronsky at the ball, by the quadrilles, waltzes and mazurkas. But some minutes into the reading they noticed, one by one, the intense concentration etched on Carla’s petalled brow. She had folded one leg up against her chest, her slender arms encircling her knee. This was how she always sat, in her own embrace. And for a few seconds more, she held her pose, deepened her frown, delighted in her audience, before she too, not exactly knowing what was funny, burst out laughing.

An actress, Heinrich thought. Years later, this is how he would begin his tribute to his sister…She was an actress.

As far back as each of them could remember, their mother had read to them. Folktales, Mörike’s Peregrina poems, Goethe, E.T.A. Hoffmann’s sinister stories that made their hair stand on end, or Theodor Storm’s sentimental ones awash with wind, sand, sea and mist, where the moon swam from its cloud cover, and where in summer on wooden benches in the shade of linden trees young boys listened to the chronicles of old men’s lives. As soon as she discovered new books for herself, thrilled especially by heroines who were themselves readers of the same novels she had lined up on her shelves, she read selections to her children. They were captivated as much by their mother’s dramatic ingenuity – she could be a haughty princess, or one of Fritz Reuter’s roughest peasants speaking dialect – as by the language, crisp or languorous, the spin or tease of verse, the ever-new suspense of stories they’d heard a dozen times before.

Tommy wanted to know how characters clung to life. He held a toy soldier tightly in his hand. To live, to live on and not die, like Frederick the Great who had inspired his troops to persevere. One day, the novelist Thomas Mann would write that all the heroism lies in enduring, in willing to live and not die. At the end of the reading hour he often became aware that his mouth had stayed a little open and his eyes were half closed, that the rhythm of his mother’s voice echoed in the warm, gentle pulsing of his blood as it coursed through his body; there was a wavelike rushing in his ears.

Even more memorable than these sessions in the library were the bedtime stories Julia told her children, who half reclined on pillows before sleep, or sat on the floor of her room as she dressed to go out. Tommy fastened her pearls. Heinrich sketched. For herself Lula dreamed of ruffled dresses and festivities. And Carla played with a collection of fans, fluffing their feathers or tracing their painted landscapes with her finger. All the while, intrigued by the romance of their family heritage, they listened closely to their mother’s childhood reminiscences.

The fourth child of Maria da Silva, of Portuguese-Brazilian descent, and Johann Ludwig Hermann Bruhns, a North German coffee and sugar merchant, Julia Mann was born Julia da Silva Bruhns in 1851, while her parents were en route between the Brazilian coastal towns of Angra dos Reis and Paraty. She was not yet five when her mother died in childbirth in 1856, seven when she, her sister, brothers and father made the two-month journey to Lübeck, where the girls, under the guardianship of their widowed German grandmother, were to be educated. Obliged to attend to his business in Brazil, her father bid her a sad farewell and returned to South America with his sons. Through death she had lost her beloved mother, and then through distance that seemed as sundering as death, father, brothers, home and language. Julia mourned as only a child mourns, with an unwavering fidelity to all she’d lost.

Later she re-created for her children what she always longed for. She coaxed their limber imaginations to the doorways, windows and verandas of her childhood home, the Fazenda Boa Vista, to look in one direction across the Bay of Paraty, in the other, along a dense wall of forest. She asked them to choose which way to go, towards the sea or jungle, and so to select their favourite stories.

To convey the allure of the sea, she would tell them she was fishing for words, prompting her audience to call out colours – sapphire, turquoise, emerald, ink – with which to paint the water, where it lapped onto pale sand, where they waded, swam, then deeper, where they rowed. Shells and rocks, she incanted, ships, islands, the horizon. Silver at dawn, copper at dusk. Within this glistening shorescape, she unfurled a series of adventures made even more incredible by the occasional appearance of a powerful sea-goddess or a temperamental, shape-changing serpent.

Their mother said that when she was very young she had heard the beat of the green heart of the jungle. Monkeys, parrots, toucans, hummingbirds, orchids, flowering climbers, glass-winged insects, with every retelling the bounty was augmented. Each of the children entered their mother’s trancelike pact of remembrance, and claimed an affinity with this closely woven tapestry of sound and scent and light. Lula and Tommy thought that their darker colouring most closely matched their mother’s, and Tommy convinced himself of a special mutuality, that certain exotic racial characteristics in his external appearance had come to him from her. They were unaware that in order to enhance her own romantic image of herself, she dyed her hair. Many years later, writing Death in Venice, he might still have wiped his brow with his pocket handkerchief when imagining – on his hero’s behalf – crouching tigers, creeping tendrils, rising sap, and a hairy palm-trunk thrusting upwards from rank jungles of fern, from among thick fleshy plants in exuberant flower…

Carla was sure that she closed her eyelids, fringed with long black lashes, just as her mother did, slowly, to be transported to faraway places and fabled lives, daughter like mother.

Heinrich had no need for special claims. When he was born, 27 March 1871 (the year Germany became a nation), named Luiz Heinrich, nicknamed Heine, his mother was barely out of her teens, and for four years he was her only child. He was the first of all his siblings to hear her laugh out loud like a schoolgirl, or whisper conspiringly, play Chopin, or sing Lieder, sweetly, to herself. The first to learn that she sometimes disappeared into a terrible tumescence…of what, he did not know…of melancholy…and that his childish kisses and embraces made her sigh, but that he could not console her. In equal portions, their relationship combined intimacy and distance. I sit in front of her desk, playing with a small bronze box, its lilac lining effusing a magical scent. In this box, or perhaps in another, he found feathers, shells, tiny rings made from the tailtip of an armadillo, a little black ragdoll she called the negrinho, and most curiously of all, a leathery hand-sized purse which was the large dried flower of the golden chalice vine, Solandra maxima. A neat circle of holes pierced near its mouth was threaded through with faded velvet ribbon; it was full of clinking foreign coins.

Some objects are the shape of thoughts. Some thoughts illuminate the dark, like swamp lights, constellations, lines of narrative. In Los Angeles, in the dead eye of night, without conscious effort, Heinrich Mann sketched his childhood. He was a boy stretched out in a summer garden, daydreaming, picturing the adult world just outside his reach. A woman who resembled his mother turned away from a man, an officer with a sword at his side. Who was this man? Was she rejecting him, or flirting? Was it a game? Water spurted from a fountain, unambiguously. There was a walled garden, a house, and inside the house, a baby in a cradle. From courtship to consummation and conception, to birth, his own birth, or one of his siblings’, in one round scene.

The old man remembered how as a boy he had once watched his parents as they dressed for a party, a masquerade. My father is a foreign officer, with a powdered wig and sword, I am immensely proud of him. As the queen of hearts Mama flatters him more than ever. His father – Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann, called Henry – always wore softly textured suits, and a small flower in his lapel. He was a grain merchant, head of the family firm, and a senator; a pillar of society with many civic responsibilities. He made, lost and regained fortunes. He was a man, Heinrich later said, who was unfamiliar with the idea of creative genius outside business hours, and who believed that his experience and status would one day pass to his eldest son.

Although the boy liked to read the newspaper across his father’s shoulder, and to accompany him on walks through town or rides into the countryside, he was a dreamer. He was too impressionable. When he watched marionette performances, or when his mother read him Theodor Storm’s story about a puppet theatre, Pole Poppenspäler, another world entered his imagination, and like its hero, a single glance at the stage sufficed to carry him a thousand years back in time. When his parents took him to a real theatre, he could not see the phantom line between life and art, and during the performance, deeply enchanted, he made a racket calling out warnings to his favourite actor about to be ambushed on the stage, and had to be taken home.

Germans love puppets and anarchic fools. In the form of man-children, savants, jovial tramps, blockheads, they are what you grow into if you don’t conform, outsiders that embody obscenity, contempt, ridicule, rebellion, transgression. Known as Till Eulenspiegel, Münchhausen, Kasperle, Hans Wurst. Goethe was inspired by the figure of Faust when as a child, season after season, he watched the folk-character of the same name, comical, grotesque, in the popular routine of bantering and bargaining with his Punch-like sidekick. His contemporary Heinrich von Kleist found in the marionettes’ mechanical flow of movement a superior form of dance, unachievable by humans shackled by physical and existential heaviness from the double burden of gravity and self-consciousness. The more Romantic the writer, the greater the conviction that the marionette replicates not life but its essence, its signature, that within their wooden core the dolls carry a spark of soul. No matter that the glint from the puppets’ dark pupils can be explained as light catching the metal head of a tiny nail, of the kind that cobblers use to fasten together the upper and lower leathers of a shoe. A favourite in the Mann household was Hoffmann’s tale Der Sandmann. The story’s protagonist Nathanaël was the victim of his own imagination. As a child he was overcome with a terror of the fabled Sandman, who prowls at night to steal the eyes of wakeful children. As a young man he suffered from his misplaced and unrequited love for a doll-like creature. Like myriads of eyes, dark meanings lurk in every corner of his life and their burning gaze drives him to madness and death.

Heinrich and Tommy, Lula and Carla, and later their youngest brother Viktor played with marionettes at home, and with model-theatres for which the figures and scenery came as sheets of paper cut-outs that had to be assembled. The conventional Papiertheater repertoire included operas like Lohengrin and The Magic Flute and plays by Shakespeare, Goethe, Schiller and Kleist, which the children received as Christmas gifts. They were also inspired to create their own plays. The writing of scripts, the painting of backdrops, the drawing and cutting-out and colouring-in of figures, the placing of them on stands, the invention of sound effects – dried peas or lentils in a carton for rain, or for applause – followed by rehearsals, and family performances, kept them happily occupied throughout the long Northern winters.

Inside the mighty church of St Marien, not far from their home, a thirty-metre-long eighteenth-century copy of a fifteenth-century fresco of the Dance of Death impressed all who saw it. Created in 1463–after the plague had ravaged Lübeck’s population several times – the twenty-four life-sized representatives of social rank, from pope to empress, duke, doctor, merchant, maiden and newborn child, are invited by a troupe of black skeletons to join hands in a dance, a farandole. The Black Death as punishment for earthly sins. But who leads in this danse macabre? It is the worldly dancers, with their flourishes of colour and choreography, who are keeping time, who are the death-defying custodians of life and energy.

Nonetheless Thomas Mann later claimed that he and his brother were strongly influenced by the shadowy atmosphere of Lübeck, where twisting Gothic alleys and hidden corners seemed to be haunted by something very old and pale, emotionally deformed, spiritually diseased, a remnant of the hysteria of medieval times. He said Lübeck was the city of The Dance of Death. Hans Christian Andersen, who visited St Marien in 1831, thought he detected ironic smiles on the skeletons’ faces, and was moved to write a story about a boy called Christian who asked for paper reproductions of figures from the Dance of Death to play with. Most likely, for the Mann children, those images in all their ambiguity would have provided rich material for theatrical productions and night terrors. The church fresco was destroyed in the bombing of 1942.

When Heinrich painted scenery for family performances, he thought that one day he’d become an artist. The puppet theatre also nurtured Thomas’s fantasies. Here he served his apprenticeship for the craft of writing and gave himself a foretaste of the hot glow of success. In one of his earliest stories, ‘Der Bajazzo’ (‘The Dilettante’), he transposed a pastime normally shared with his siblings, into one of intense solitude, as if he’d been an only child. The narrator describes his favourite childhood activity, of creating, directing, acting out an opera alone behind the locked door of his room, where he plays every part, from librettist, to usher, to members of the audience conversing before the show. He even cuts a hole in the paper-curtain for his paper-actors to see if the performance is well attended, which of course it is. He tries to conduct the orchestra, sing the different voices, and play various instruments, all at once, there is great applause, and as concert master he takes a low bow to thank the players and the audience. At this point he could only imagine a full house, but the large numbers of people, sometimes several thousand, that later attended his readings and lectures would count among his greatest adult pleasures.

Their mother’s desk did not have a lock, and every morning before going to school Heinrich placed his small violin inside, high enough for Tommy not to reach it. It should have been a safe place. He later wrote that the instrument was his joy, or the promise of joy one needed to look forward to each day. But when he returned he often found that it had been played, or rather played with, since sometimes it was damaged, with loose or broken strings and scratches. He wondered who helped his brother take it out and then replace it. When this happened once too often, Heinrich raged. His behaviour was met with dark looks and sharp words from his mother. One day he came home to find his violin in pieces. He cried. You see, his mother said, it no longer matters if it was yours alone or if it belonged to both of you, now that it’s broken. Complex reasoning for a young boy to comprehend.

The brothers were tied by bonds of love and jealousy. There were fallings-out, short and long periods of not speaking to each other, followed by peace. Tidal forces of affection. During one of the family’s summer holidays in Travemünde, a seaside resort fifteen kilometres from Lübeck, to cut the ice, Heinrich raced Tommy to the shore and deliberately fell over in the sand to let his brother win. Then they dipped their toes into the blue-green water – measured in degrees of coldness, even on the hottest day – and daring one another, they both plunged into the waves.

Two hundred fifty rivers drain into the glacial basin of the Baltic Sea; as the largest volume of brackish – in some parts almost fresh – water on the planet, it contains only about a quarter of the salt of oceans. It was once a lake and has been a sea for a scant 7, 000 years; now it is related to the North Sea, and distantly, to the North Atlantic, via narrow straits. Sudden wind changes and violent storms make it hazardous for ships; on its bed there are more rotting, rusting wrecks than in any other sea on Earth. Heinrich told his younger brother, as they dived into the viridescent waves, about a marine landscape of ships’ hulls, broken masts, treasure chests and cannonballs, crusted with shells, flagged with fluorescent algae. He said that the Baltic was a cemetery. That swimming further out, they must be careful not to touch the bottom with their feet, for fear of kicking up old bones; that the water of the Baltic tastes like blood.

In Los Angeles, in the not yet broken darkness before dawn, Heinrich cast pencil markings across a new page of his sketchbook: 1886, he calculated, May or June, when their mother began to read Anna Karenina to them, for soon afterwards they were on holiday, and the book, unfinished, had been left at home.

Travemünde in July and August was a place of milk-washed skies, sand like silk against the skin, shells picked up and left randomly on windowsills and gateposts. Everyone rose early and retired late; with a Nordic thirst for light and warmth, accumulated over too many months of winter, they lavished themselves with sun. At the water’s edge was the familiar line-up of bathing machines which one entered clothed and exited by a short ladder, temporarily amphibian, for health from seawater and sea air. From the promenade, and from a maze of manicured gardens, with the crunch of pebbles underfoot, came bursts of laughter and sounds of calling to acquaintances, in a great variety of dialects and languages. Holidaymakers wearing mostly white, men with straw hats, women twirling parasols, strolled, or gathered with contagious leisure, against the backdrop of the hardly incongruous row of picturesque Swiss chalets, or the Musiktempel, or the Kurhaus, where one sipped salt water. On the beach children chased raucous seagulls, and with Lilliputian spades built forts and castles; with their bare hands they dug wet sand, urgently, to make channels and as the water rushed in and out, and the walls threatened to collapse, they hurried to secure them; if someone wilfully destroyed these masterworks, there were slaps, kicks, howls, tears.

A youth carrying a book might slink towards the dunes to read or daydream, unsure of his status in society, while others of his age rehearsed the arts of courtship in every little way. Two or three young people walked in the direction of the lighthouse and the Brodtener Steilufer, a cliff from which great chunks, trees even, sometimes fell into the sea; at its base was a narrow strip of sand, a renowned treasure trail for fossil hunters, leading between Travemünde and the fishing village of Niendorf.

Along slowly darkening paths some who stayed out late followed the rituals of glow-worms – wingless female beetles, Lampyris noctiluca–that lit up their bodies to attract the unilluminated flying males.

Like many others, the Manns probably hired an open carriage for excursions to villages further along the coast, Niendorf, Timmendorf, Scharbeutz, where they would eat freshly smoked fish for lunch, herring, sprats, or eel. They stopped to buy berries from a farmer’s stall, and the old coachman took a nap while they picked great bunches of blue lupins that grew beside the road, and strawflowers from a white-gold carpet covering the dunes. As they headed back to Travemünde for dinner, fields on one side, sea on the other, Lula coughed from the dust kicked up by the horses, and Heinrich noticed that Carla was almost asleep against his chest, that Tommy was sunburnt.

Light and shade flickered hypnotically as the carriage rolled through a forest of beech trees. The coachman told stories. Not only amber washed up on these shores, he said, but people too, the living and the dead. He recounted the terrible storms he’d experienced in his lifetime. The worst by far were the winds that caused the great flood of November 1872, when it seemed as if, in the black of night, the sea would altogether claim the land. Trees bent like straw, buildings were destroyed, others filled with sand, people and animals drowned, those who had managed to climb onto roofs felt the walls collapse below and were set adrift. As the water subsided, survivors were found in treetops and boats on meadows far from the shore.

Going further back in time, the coachman thought it was the summer of 1837, he was a young man then, courting the innkeeper’s daughter, and he remembered that travellers on their way by ship to other Baltic ports had to wait for the wild weather to abate before continuing their journeys. The wind was so powerful that a beehive was tossed high into the air and carried to an island with its swarm intact. For days the inn was full of restless people, pacing, smoking, drinking; not a rowdy bunch at first, but they grew irritable as the conditions worsened. He remembered one man going to Riga who was increasingly impatient with the delay, intolerant of the crowded space, red with anger; how the volume of his voice rose from his chest, producing rapid streams of curses; how he slammed the wooden benches with his fist. To calm him, the innkeeper showed him a book which absorbed the man so completely, he was seen musing, making notes, tapping rhythms on the table. When the storm passed and it was time to continue their journey, his wife had trouble rousing him from his concentration. The fellow’s name, the coachman revealed as he pulled up at the hotel entrance, was Wagner.