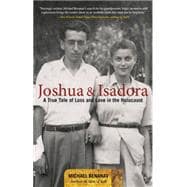

Michael Benanav is the author of Men of Salt: Crossing the Sahara on the Caravan of White Gold. He writes and photographs for the travel section of the The New York Times and for LonelyPlanet.com. He lives in northern New Mexico.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

On December 3, 1944, theTorosdebarked from the Romanian port of Constanta. The iron plates had been stripped from ship’s exterior for fear they’d attract the magnetic mines that bobbed in the Black Sea. Rags were jammed into cracks in the now-naked hull to staunch the water seeping through them.

The cargo hold – a cavernous space below deck normally used to ferry cattle sheep across the Bosphorus – had been converted into a floating barracks. Makeshift bunks of bare board, two rows high, were installed to starboard and port. Refugees lay three or four across, head to foot, head to foot, down the length of the hold. Baggage was heaped below in disarray. The lingering odor of livestock was obscured by that of breath and bodies and vomit.

Up above, a phony Red Cross flag flew from the mast. Passengers were deliberately staged on the windy, sea-sprayed deck, their heads, arms, and chests wrapped in bandages, completing the ship’s disguise as an aid vessel – a precaution taken to divert unwanted attention from the Luftwaffe bombers patrolling the clear, sapphire sky.

The refugees were Jews who, by chance or savvy and usually both, had slipped through the fingers of Nazi Germany’s death grip and escaped into the part of Romania that had fallen behind Russian lines. Meanwhile, most of their kin, if still alive, were in concentration camps, where more people were being herded into gas chambers in less time than ever before; with the Russians advancing daily from the east and the Allies closing in from the west, the Nazis raced to finish the gruesome task they had set for themselves before the inevitable fall of the Third Reich.

The refugees – homes destroyed, families murdered, memories haunted – were leaving for Palestine, where some hoped to help build a new nation, and others to just rebuild their lives. But magnetic mines and the Luftwaffe weren’t the only immediate threats to their dreams.

The British, who had controlled the Holy Land since the end of World War I, vigorously enforced a policy banning Jewish immigration in an effort to stem the zeal of Zionists working to create an independent Jewish homeland there. British naval vessels could and did turn back, and even fired upon, boats carrying Holocaust survivors, in order to prevent their landing in Palestine. Thus, those who had narrowly escaped the war with their lives put themselves at mortal risk once again by attempting the passage.

But the British, perhaps out of a perverted sense of fair play, had left one loophole in their anti-immigration policy (which was not to remain open for long): they agreed to give visas for entry into Palestine to Jews coming from Turkey. So it was for Istanbul that theTorosaimed, hoping that bribed Turkish officials would allow the boat to sneak into port.

Among the teeming swarm of 1100 passengers was Isadora Rosen. Twenty years old. Skinny and meek. Eyes like dark moons arisen on a face that had forgotten how to smile. She was with her younger brother, Yisrael, who was seventeen. Their parents, dead. They were two of the 600 orphans on board who had somehow emerged from the frozen ghettos and camps of Transnistria – the “Forgotten Cemetery” of the Holocaust, situated in Ukraine – to where Romanian Jews had been deported in 1941, in what would prove to be a test run for Hitler’s Final Solution. Though less organized, less coldly efficient, conditions in Transnistria were no less cruel than at Auschwitz or any of the Holocaust’s icon camps.

There, Isadora had lost most of her family, a few of her toes, and nearly her life.

After Transnistria was liberated by Russian forces, the Romanian government, which worked hand in hand with the Germans to deport the Jews, were forced to gradually readmit those who’d survived. But the refugees were discouraged from staying. Thus, an anti-Semitic regime became odd partners with Zionist organizations in an effort to send the remnants of Romanian Jewry to Palestine. And the so-called Transnistrian orphans were a priority for both groups.

Disoriented. Frightened. Isadora was overwhelmed by the mass of ragged, unruly characters on the overcrowded ship. She had one relative, an aunt, who’d gone to Palestine before the war, but had no idea how to find her. The past loomed behind her like a nightmare, the future before her like a void. With the ship pitching as it motored across the sea, she and her brother went below deck, where all but those masquerading as war wounded were encouraged to ride out the voyage. They squeezed down the aisle between the bunks, searching for a place to lie down.

A kind-seeming middle-aged man motioned to the confused orphans. “There’s some room over here,” he said, and pressed closer to the body between himself and wall. Yisrael climbed up first and settled in beside their new friend. Isadora lay on the outer edge of the board.

The hold was filled with a metropolis of sound. Talking and creaking and moaning and retching and yelling and snoring and sniffling. Isadora lay there, still, in the faint amber light from the lamps hung from the ceiling. Despite the noise, the discomfort, the anxiety, she fell asleep – something that people who’ve endured great suffering acquire the ability to do regardless of their surroundings.

She awoke sometime later, feeling the pressure of a hand upon her shoulder. She thought it was Yisrael, who must have shifted in his sleep. But the hand began working its way down her body, groping for the breasts she barely had. Alarmed, she turned and saw an arm draped over her brother’s figure, and a questioning smile on the face of the man who’d invited them onto the bunk. She shoved the hand from her body and spastically propelled herself down into aisle. Pressing her way between those that stood between herself and the door, she stumbled over suitcases and trash to the exit. She had to get out.

By this time, night had fallen. The sky was a canopy of stars glistening like sequins on a jet-black dress. Isadora didn’t notice; she collapsed in a heap on the damp, cold deck. The frigid air stung her cheeks. She covered her face with her hands. And she wept.

Before long, the beam of a flashlight shone between her fingers. It was held by Joshua Szereny. A Czech citizen, he’d escaped over the Apuseni Mountains from a Jewish slave labor unit in the