What is included with this book?

| The Uninvited | p. 1 |

| The Gift | p. 29 |

| Men | p. 55 |

| Working Mother | p. 79 |

| Talking to the Dead | p. 99 |

| Meeting the Hipster | p. 119 |

| A New Start | p. 137 |

| The American Adventure | p. 163 |

| Wedding Bells | p. 183 |

| America | p. 207 |

| Epilogue | p. 227 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 237 |

| About the Author | p. 243 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter 1

The Uninvited

I was three years old when I saw dead people for the very first time.

We were living in a flat in Birmingham, in Central England, our family's first real home, and I soon discovered that we weren't alone. Strange faces, balloonlike and oddly translucent, came floating in and out of the walls of my room, and because they were slightly blown up, as if filled with air, they seemed a little clownish. But there was nothing funny about them.

I went to tell my parents. "There are people in the walls of my room," I said.

"What people?"

"I don't know. All sorts of people."

Mom took me by the hand and walked me back. "Where?" she said.

"Well, they're gonenow, but they were here a minute ago."

"You're making this up."

"No, I'm not."

"Who are they, then?"

"I don't know. Just people, some of them look like clowns."

"Clowns? It's just your imagination! Go to bed."

The next night, the faces were back. I went into the lounge andrefusedto return to my room. My parents were just about to go to bed and, unhappy at the prospect of another sleepless night, my father gave me an angry look and marched off. "If you want to stay on the sofa all night, that's fine, but I'm going to sleep."

I stared at him, even as he switched off the lights and left me in the dark, but feeling guilty, he returned a few minutes later and found me sitting there, still staring. I hadn't moved.

"Why are you such a defiant child?" he said.

"What's 'defiant'?" I asked, scowling.

He picked me up, carried me to bed, plunked me down, and stormed off without saying a word.

For the next few months, the drama continued, sometimes two or three nights a week. An endless array of faces, ghostly and insubstantial, would emerge from the walls, study me for a moment or two, even try to grab at me at times, then just as suddenly dematerialize. Some of them actually addressed me, but I could never make out what they were saying, and they scared me.

"What do they say?" Mom asked.

"I dunno, but one of them comes through the lightbulb and tries to yank my hair."

"Comes through the lightbulb?"

"I just see her arm."

"How do you know it's a girl?"

"Dunno," I said, shrugging my shoulders. "I just don't think boys pull hair."

Exasperated, my parents finally moved me into the spare bedroom, but the faces were back that very night. Bony old men. Angelic boys. Old ladies. Thin girls with pinched cheeks. I went to get my mother, to show her, but by the time we returned, they had disappeared.

"There is nothing there," she said. "It's just your imagination. Go to sleep."

After tucking me in, she curled up in bed with me and stayed until I fell asleep.

There were nights when I would lie in bed scared, begging the uninvited visitors to leave me alone. I'd bury my head under the covers, thinking they would go away if I couldn't see them. And other nights I'd shout at them, "Go away! This is my room! I don't like you!"

My parents were concerned, but they thought I just had a vivid imagination. This was thirty years ago and therapy wasn't an option in my family. We never really showed emotion, and seeing a therapist wasn't even in the realm of possibility, so they dealt with my complaints by ignoring them. And it worked! Whenever I mentioned the faces, they would roll their eyes and continue what they were doing. In time, I stopped talking about them altogether, and soon enough -- taking a cue from my parents -- I began to ignore the spirits. They still came, of course, but they didn't bother me anymore.

I also began to ignore my parents -- or at least that's the way it appeared. "Lisa! I'm talking to you! Are you listening to me?"

I would look up from my perch on the floor, where I was playing.

"What?"

"What is wrong with you? Are you deaf?"

As it turned out, I was hard of hearing. I had compensated for this defect, unknowingly, by reading lips, which I guess I'd been doing ever since words first began to make sense to me. If I didn't look at a person directly, I couldn't really make out what they were saying to me -- which was the same problem I had with my nightly visitors.

When I was five, Mom took me to Birmingham Children's Hospital, where we were told that the tubes to my ears were almost completely blocked. The surgeon cleaned them out and removed my tonsils and adenoids for good measure, and when I awoke I could hear just as well as the next person. This was wonderful indeed, but -- even better -- every afternoon at three the nurses showed up with big scoops of ice cream. I loved ice cream so much I didn't want to leave the hospital!

In the summer, I would play in the big grassy area in front of our building, waiting for the ice cream man to show up. When I heard him coming, I would shout up to the third-floor balcony, "MOM!!!" Moments later, a fifty-pence piece would come sailing off the balcony, tumbling end over end. I would watch like a hawk to see where it landed, then I'd grab it and hurry off to meet the ice cream man.

Except for the haunting faces, life was great, especially now that we had a home of our own. My mother, Lorraine, stayed home in those days to care for me, and my father, Vic, worked as a self-employed contractor. Previously, we had lived with my father's parents, Jack and Josie, in West Heath, Birmingham, They had a two-bedroom house with a lovely, long garden, and I'd run up and down the entire length of it tirelessly, urging my grandparents to look at me. My grandfather would always be out there, tending to his plants, and he always humored me by looking over.

During the cold winters, I would have snowball fights with my dad, then we'd go inside and huddle around the fireplace with the rest of the family. I especially remember Tuesday nights, because every Tuesday, without fail, Mom and Nanny Josie would go off to play bingo at the local bingo hall. I started to call my nan Bingo Nanny.

In 1976, two years after we moved into our own home, my brother Christian came along. I still remember watching my mother carry this bundled little creature into the house for the first time. I hoped his constant screaming would scare off the spirits, but they didn't seem to be troubled by the crying; in fact, they weren't even vaguely interested in him.

Eventually, tiring of hearing me complain about the visitors, my parents had me switch rooms with Christian, and my mother's mother, Frances Glazebrook, paid to have the room redone. She and my parents chose Holly Hobbie wallpaper. Holly Hobbie was a little girl in a blue chintz bonnet, and she was supposed to personify childhood innocence. She was cute but she had these eyes that freaked me out at night. Now I had to deal with the spiritsandwith Holly Hobbie, staring at me.

In September 1977, I went off to nursery school. I was four at the time. Mom took me the first day, but the second day I was sent off to join the parade of children who made their way down the path every morning, past our building. I tried to be brave about it, but when I got there, I saw that most of the other kids in my class had arrived with their mothers, and that one of them had actually brought flowers for the teacher. I was so upset that I ran all the way home in tears to find my mom. "You're supposed to walk me to school," I said, blubbering. "And you forgot to bring flowers for the teacher."

We went outside and picked a few flowers, and Mom walked me back to school. I gave the flowers to the teacher, who was most appreciative, and settled in. I enjoyed school, but I was shy, and quite insecure. I had a hard time making friends, and the year proved somewhat lonely for me.

I'd gotten used to the visitors by then, but I still huddled under the covers from time to time, trying to ignore them. One evening, just as Mom called me to dinner, a distinguished-looking gentleman, nicely dressed in a brown jacket and matching trousers, appeared in the hallway and followed me to the dining room. It was awholegentleman, not just a face or an arm.

"Don't eat your peas," he said.

"Huh?" I said.

"Don't eat your peas or you'll die."

My dad looked at me, perplexed. "Are you talking to one of your imaginary friends?" he asked.

"He's not imaginary," I said, pointing in his direction. "Can't you see him?"

He looked toward the spot I'd indicated, but saw nothing. "Who?"

"There! He's standing rightthere!"

"Don't eat your peas," the man repeated.

"Okay," I answered.

"I don't see anyone," Dad said.

"He's telling me not to eat my peas or I'll die."

My parents thought I was making it up because I didn't like peas, which Ididn't, but the man was standing there, clear as day. They didn't believe it, but they gave up trying to talk sense to me. "Okay," Mom said, rolling her eyes. "Don't eat your peas."

I recently found out that my dad's great uncle always had pie, chips, and peas for lunch, and one day -- a few years before I was born -- he choked on a pea and died. To this day I have a terrible phobia of peas.

My favorite food at the time -- the only food I cared for, really -- was a cheese sandwich. Not evengrilled, mind you; just two slices of bread with cheese and salad cream, which is like mayonnaise with horseradish.

One night, there was a tomato on my plate and the man was back. "Don't eat the tomato, either. You could choke. Avoid anything with pips."

"Okay," I said.

"What?" Mom said.

"I wasn't talking to you," I said.

"There's nobody there," she said.

"He's right there, Mom! He told me not to eat the tomato."

"No, he's not. It's just a ploy to avoid eating your vegetables. He's just like your monkey."

She had a point there. I had an imaginary monkey, whom I'd named "Monkey." I took him everywhere with me because he was good company and nice to chat with. He was a talking monkey. We were inseparable. If I ever forgot him, I moaned until we went back to the house to get him.

The following year, when I was five, we moved into a council house in Tillington Close, in Redditch, Worcestershire, twenty miles south of Birmingham, and that's where I lived until I turned nineteen. It was a mid-terraced, red-brick house with three bedrooms, a dining room, and a spacious living room, and there was a huge patch of grass out front that we shared with our immediate neighbors.

I was so excited to move. I chose my new room, hoping to leave my visitors behind at the old flat. But the faces were back the very first night -- different faces. I was determined to start afresh, so I ignored them. I started at the Ten Acres First School, which was close by, and on my very first day I made friends with Samantha Hodson, who remains a close friend to this day. I was a little behind at school, mostly on account of my deafness, and I couldn't read and write as well as the other kids, but I caught up quickly and grew to love the place. I loved sports and music and I especially loved singing; I was delighted when I was asked to join the choir.

There was a girl in my year and for some reason, I became very competitive with her until we left school at eighteen. Her name was Helen Waugh, and she could play the recorder and even read music, which impressed me to no end -- and made me very jealous (even though I liked her). Motivated by her superior skill, I learned to play the recorder and read music. Then she took up the violin, and I took up the violin. This went on for years and years, and because of Helen, I now have varied taste in music. I also sang, danced, and played sports; my days were so full that I fell into bed exhausted every night, with absolutely no time for my otherworldly visitors.

On Saturdays, my little brother and I would usually go round to visit my maternal grandmother, Frances, and my grandfather, Jack, at their home in Bartley Green. My cousins would often be there, and we'd dance and run around and shoot tin cans in the garden with an air rifle. Sundays after lunch we'd go visit my father's parents, Jack and Josie, and the adults would always get into long debates about Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister, who -- if you asked my granddad -- was ruining the country. There were no cousins here because my father was an only child, so in a way it felt more special. It was just me and Christian, and since he was still an infant, I got most of the attention.

On Sunday nights, we always got home late, and I'd often pretend to be asleep so that my dad would wrap me in his arms and carry me to bed. On one such night, genuinely exhausted, I had a very vivid, scary dream. In the morning, still rubbing the sleep from my eyes, I arrived at the breakfast table and dropped into my seat. "Do you remember those dogs that mauled me?" I asked.

"What dogs?"

"I don't know what kind they were. Just three big, black and brown dogs.

"Don't be silly," my mother said. "You've never been mauled by dogs."

"Yes I have," I said.

"Quiet down and eat your breakfast. It's just your imagination."

"But I know it happened!" I protested. "Why are you telling me it didn't?"

Once again they ignored me, which only upset me more. I knew it had only been a dream, but somehow it wasreal. In the dream I was maybe three or four years old, with long, wispy, platinum blond hair. Myactualhair was thick and light brown and cut in the shape of a bowl, tapering inward along the sides of my face -- we used to call that a Purdey -- but years earlier I'd had hair just like the girl in the dream. I was only seven at the time, and I knew nothing about past lives or reincarnation, but I was convinced the dream was real. The little girl was not me in this life, but she felt like a version of me. "There were three big dogs," I insisted. "And they were chewing me. I could feel their teeth sinking into my skin."

My mom tutted and rolled her eyes.

"But it's true! It really happened! I even heard a woman screaming, and it might have been you."

Mom gave me that look:Here we go again.

"I'm not making it up!" I insisted. "It really happened!"

"Finish your breakfast and get ready for school," my father said.

I couldn't understand why they didn't believe me, especially since my mother's mother, Frances, experienced visions that came true and saw dead people too. Also, my father's mother, Josie, read tea leaves and often spoke of odd visions, vivid dreams, and strange sensations. Then again, I'd often heard my dad scoff about these "socalled gifts," saying he didn't believe a word of it. He didn't believe much of anything, to be honest. Religion, for starters. I went to a Church of England school, but neither of my parents attended church. "I don't believe in God or Heaven or anything beyond this life," my father used to say. "When you're dead, you're dead."

My mother was more open, and she often told me that she felt that something was in store for all of us after we passed away. She didn't think God or Jesus had much to do with it, however, and she certainly didn't spend much time worrying about it.

I remember once asking my parents why I hadn't been christened, like most of my friends, and my dad was pretty blunt in his response: "Because I don't believe and I'm not a hypocrite," he said. "If you want to do it, then do it, but you'll follow through by going to church every Sunday. It's up to you."

I had plenty to keep me busy on Sundays, so I decided against it. But it wasn't based on lack of faith. I was a child and I simply didn't know what to believe, and it was clear that my parents weren't going to be particularly helpful in helping me decide.

Just before I turned eight, my maternal granddad passed away, and my Nan Frances had to adjust to life as a widow. Almost immediately after the funeral, which, for some reason, I was not allowed to attend, she began going to the local Spiritualist Church, something she had denied herself when her husband was alive, since he was another staunch nonbeliever. It was evident almost from the start that she had a gift, and before long she was performing public demonstrations. Her favorite venue was the Harborne Healing Centre, a spiritualist organization in a suburb of Birmingham, where she would communicate with people who had passed over, sharing their messages with their loved ones. She started doing private readings at her home, and she was so good that before long she was traveling around the world to read for some of her wealthier clients. Because of this I took to calling her Airplane Nanny.

From time to time, I would hear my parents talking about her. My father was dismissive, of course, but my mother was curious and more than a little impressed. Frances had segued effortlessly into the next chapter of her life, and she was adjusting quite nicely.

I never asked about any of this, of course, because I somehow felt the subject was off-limits, but I loved visiting her. She wasn't your typical grandmother, like my dad's mom, who baked cakes and played with us and made lovely dinners. No, Airplane Nanny was glamorous; she had no interest in playing games. She had her hair done every week, loved jewelry, and really loved to laugh. She had a wild, almost bawdy laugh, and when she started you couldn't help laughing too -- even if you didn't understand the joke.

She was also thoroughly modern. She always had the best phone, or the latest answering machine, or the newest VCR. But she liked old things too. She had a collection of brasses that had once been worn by Shire horses, those great big draught horses that were once used to haul beer from the breweries. She kept them along with a huge, shiny brass plate above the fireplace; they were her pride and joy. She also had a brass doll with a little bell tucked up inside its skirt, which sat on the mantel, and I never got tired of ringing the bell -- though everyone else did.

Inevitably, I began to cross paths with some of her clients, and I'd be told to make myself scarce. "You'll have to go play outside," she'd say. "I have someone coming to see me."

"What is it these people come see you about?" I finally asked her. I couldn't understand what these people wanted from her, or why she never answered the constantly ringing phone.

"I'm clairvoyant, I do readings," she explained. "I talk to their loved ones who are in spirit and am able to look into the future."

"Oh," I said. I didn't think to ask her how she did this, but I suspected it had something to do with the cards she kept on the mantel. I had asked about the cards once before, and she had been quick to respond: "You must never touch them. These are very special cards, they are not playing cards, and they're not for you. Not yet, anyway."

When I was nine, I had another very vivid dream. "Did one of our houses burn down when I was little?" I asked my parents.

"Why would you say something like that?" Mom asked.

"I had a dream last night. I was surrounded by fire. But I woke up before I burned to death."

"I hope you don't talk about these things outside the house," my dad said with his usual dismissiveness.

"I don't," I said. But that was only partly true. I did share some of them with Sam Hodson, my best friend, because I knew she wouldn't tell.

"It didn't actually feel like a dream," I went on. "It felt like it was really happening to me."

"You have an overactive imagination," Mom said.

"I can't have," I said. "My teacher is always telling me to be more imaginative."

Tuesday after school I usually went to Sam's house, played, and had dinner, staying until 7:30, and Thursdays she came to mine and did the same. Occasionally, we had sleepovers. One night we were at my house, and we were talking about my grandmother, Frances, who was beginning to get quite a reputation around Birmingham. "Do you think you have the gift?" Sam asked me.

"The gift? I don't know that it's a gift. It's just something she does. She reads the cards and tells people what she sees."

"It's agift, I tell you," Sam insisted. "I heard it runs in families."

"Where did you hear that?"

"I'm not sure. On the telly, I think. Tell you what, let's see if you have the gift. Have you got a pack of playing cards?"

With uncertainty, I went off to fetch the cards and handed them to Sam. We sat cross-legged on my bed and Sam set the deck in front of her. She asked me to try to guess the cards, and she peeled them off the deck, one at a time, and held them directly in front of her face.

"Ace of clubs," I said.

"Right!"

"Four of hearts."

"Right again!"

"Nine of diamonds."

"Oh my God!"

We went through all fi fty-two cards, and I got every single one of them right. Sam was open-mouthed with shock. "Lisa!" she said. "That was incredible. I can't believe it. You have the gift! You have the gift!"

"No, I don't," I said. "Look behind you. The street light shone through the window and made the cards practically transparent. I can see right through them!"

Even after I showed her, she refused to believe me, thinking there was more to it, and she insisted we try something else. It was after ten o'clock, and I'd put out the lights because we were supposed to be asleep, but she looked around the darkened room and her eye settled on one of the bookshelves. I had a collection of about a hundred Ladybird books, which I loved. They weren't in any particular order, and in the dim light the titles were impossible to see.

"Tell you what," Sam said. "I'm going to touch the spine of one of the books, and you're going to tell me the title."

"Okay," I said. "But I'm going to need contact with the book through you."

"Why?"

"I don't know, someone just told me to do it." It was true: I'd heard a voice telling me how to make it work.

"You're weird," Sam said, looking at me like I was crazy, but still smiling.

"I know, you keep telling me," I said.

Sam reached for my hand with her right hand, then rested the index finger of her left hand on the spine of one of the books. I started to see the image of a book I'd read at least a hundred times. "The Princess and the Pea," I said.

She pulled the book out of the shelf and brought it near the window, where there was just enough ambient light to make it out. "Oh my God!" she said. "You're right!"

We tried again, and again it worked, and we tried twice more, and both times I got the titles right. We freaked out. Then the door to the room opened, startling us. It was Mom, alerted by our girlish screaming. "What's going on here? You're supposed to be asleep."

"Mom! Guess what happened!" I said, and I told her, breathless with excitement. She listened attentively, waited until I was done, then studied me solemnly and said, "It's time for bed now, but I think you need to have a little talk with your grandmother."

Sam and I lay awake for a long time, but we didn't talk because we were both too excited -- and a little scared.

I went to see Frances that weekend, and I repeated the story. "I'm not surprised," she said. "You're a very special child."

"I bet all nans say that," I replied.

"Maybe, but this is different. You are special."

"What does that mean, exactly?"

"You'll find out more when the time comes," she said with a smile, then turned and indicated the Tarot cards on the mantle. "Remember what I said about those cards. You mustn't touch them -- or the ouija board, either, for that matter -- you are not ready," she said.

"Why? Will something bad happen?" I asked.

"No, you're just not ready," she said, patting the back of my hand. "You might attract spirits you can't deal with. But don't worry about it. We'll talk more about this when you're older." Suddenly I understood that my little visitors were spirits trying to communicate with me.

That same week, Sam decided to tell the other kids at school about me, and how I'd named four book titles in a row. "She has a gift," she said, laughing, and I could feel my face turning red. "Lisa's weird!"

I wasn't offended -- she was actually quite impressed, and she meant it in a loving way -- but I suggested that it was probably a series of lucky guesses. "No, no," she said. "You're different than us. You're special."

I had shared many things with Sam, but I had never told her about the faces, or about the dreams. Or, more recently, about other "feelings" I picked up during the course of the day. I knew if there was going to be a test before I even walked into class, for example. Or if one of the students was going to go home sick. I even remember feeling sorry for a boy who sat next to me in class, not knowing why, and two days later he showed up at school with a cast on his broken arm. Sometimes I knew the phone was going to ring and who'd be calling. "Dad, Airplane Nanny's gonna call for Mom."

A moment later, the phone would ring, and my dad would look at me like I was crazy, then go off to answer it.

The odd part was, my friend Sam was much more of a believer than I was. I wasn't even all that interested in myso-called gift, to be completely honest. It made me self-conscious. I wanted to be like other girls, not different, so once again I dealt with it by trying to ignore it. I ignored the faces that came through the walls. I ignored the chatter in my head. I ignored the vivid dreams. I ignored the quirky feelings I picked up as I went about my day. I even ignored the pains in my legs that kicked in whenever something bad was going to happen. Instead, I poured my energy into dancing, swimming, gymnastics, music, and singing, and I enjoyed myself, but a little voice in my head kept repeating the same thing:This isn't where your talents lie. Alas, in my quest for normalcy I ignored that little voice, too.

I did well in school, if not spectacularly, and I had friends, but I wouldn't say I was immensely popular. To tell the truth, I was a bit lonely as a child. I'd go about my day at school, then walk home mid-afternoon, let myself into house, and potter about aimlessly till my parents came home, which was seldom before six o'clock. (Mom was working as a seamstress by this time, and Dad was still in construction.) That's why Tuesdays and Thursdays were my favorite days, because I got to spend them with Sam: Tuesdays at her house, with her lovely parents, Sue and Ray, and her brother, Darren, and Thursdays at mine, because Thursday was Mom's day off.

By the time I turned eleven, England was in the middle of a recession, and my parents were working harder than ever, trying to make ends meet. Dad usually worked six days a week, and his spare time was spent on the golf course, and Mom only had Thursdays and Sundays off. As a result, my brother and I began to spend weekends with Jack and Josie, my grandparents. I missed my parents, and I longed to be closer to them, but there was nothing to be done about it.

That summer, and in many school holidays to come, I found myself spending long stretches with Nan and Granddad at their caravan -- a mobile home -- in Diamond Farm, Brean, which is in Somerset County, about an hour and a half from Birmingham. Those turned out to be the happiest holidays of my life.

My granddad would pack us into his red Austin Allegro, and we'd sing the entire way there. He had a great voice. We'd sing Barbra Streisand songs, or songs from the musical Fame, while Christian told us to be quiet and Nan gave us mints to stop the motion sickness. The excitement built with every passing mile, until we exited the motorway and pulled up to their home.

There were plenty of other kids who spent holidays in their own caravans, and we got to know all of them. Sometimes we'd go to the public pool in Burnham, nearby, or we'd walk the 365 steps that went up Brean Down, to look at the ancient battlements and the ocean, just beyond. We'd go in the water even though it was absolutely freezing.

At night, or when it was raining, I'd organize little parties or concerts, or get all the kids together to play cards. And every summer, in mid-July, a dozen city kids would show up with a religious organization called the Sunshine Group. They stayed for two whole weeks -- easy to spot in their bright red shirts -- and we'd play rounders with them, or cricket, or just lounge about the park getting to know each other.

Some days, I'd visit with Jack, a man my grandfather's age who spent his summer in the neighboring caravan. He was on a dialysis machine and went away every two days for treatment, but on good days he would play his violin. He had played violin with the Bristol Philharmonic, and with his help I got quite good on the violin myself.

Our caravan lacked proper plumbing, so we showered in the communal bathroom block, and we did the wash by hand. I often helped my grandmother. It was a little like traveling back in time, and I loved it.

It was there, at Diamond Farm, in the summer of 1986, that I had my first religious experience. I was thirteen at the time, and the Sunshine Group was back. This was the third summer I'd seen them, and the kids were always different, but the organizers were always the same. One of them asked me if I'd like to attend one of their meetings. I knew it was a religious thing, and I wasn't sure I should go, but I was curious, too -- and a little voice in my head told me to go.

I told my nan I wanted to see what it was like. She was fine with it, and I found myself at the Village Hall, listening to some of the organizers talk about Christianity, and faith, and about the importance of welcoming God into our hearts. It was quite intense, but I was intrigued, and I liked the hymns we sang between speeches.

Toward the end of the evening, we were asked to bow our heads in prayer. I looked around and bowed my head, like everyone else. Then I heard a man's voice calling out from up front: "If you're visiting and want to welcome God into your life, please raise your hand."

I don't know exactly what happened to me, but my hand started to rise on its own. It was not a conscious decision. Even as it was happening, I was a bit taken aback. It was as if someone had attached a string to my wrist and was lifting it up without my consent.

"You can come forward," the man said.

I raised my head and looked up, and I noticed maybe six or seven other people making their way to the front of the hall. I got up and followed them. Up until this point, everyone else was praying, heads still bowed, but this must have been their cue to stop praying.

I felt everyone was looking at us, which no doubt they were, so I was a little nervous. I found myself sitting next to a chubby blond boy with whom I'd played rounders earlier that day. I looked up. The organizer smiled at me. "You want to say a little prayer to the Lord?" he asked me.

I nodded, and closed my eyes and thought about what I wanted to say, but the organizer asked me to say it out loud. "Just say what's in your heart," he told me. "Whatever you feel is fine. Whatever comes to you will be right."

I clasped my hands in front of me and prayed: "I'm sorry if I've caused any problems for anyone, Lord. I'm going to try to be a good person. I am going to develop faith."

Even as I said these few words, I felt a little bad about it. I thought I was betraying my father, who was an atheist, and my mother, who was on the fence about religion. But a moment later the feeling passed -- I wasn't doing anything wrong -- and suddenly I was overwhelmed by good feelings. I don't know how to describe it other than to say that I felt as if this big empty hole inside me had suddenly been filled. I felt strangelycomplete.

I went back to my seat, smiling, almost giddy, and people kept coming by to congratulate me. There was something so genuine and warm about it that I was moved almost to the point of tears. I felt very close to everyone in that hall. I felt the world was suddenly beginning to make sense.

On my way back to the caravan, I was still giddy. I didn't know why I'd volunteered, or what exactly had happened, but I felt wonderful. I breathlessly described the entire experience to my nan. When I was done, she smiled but all she said was, "I'm glad you had a nice night," so I couldn't make out how she felt about it.

Still, I took it very seriously. The next day, the organizer gave me a pocket Bible, and he told me to read it now and then, and to make time for prayer. I read a little every day, and at night, when I went to bed, I always said a prayer. "Thank you for the day, God. Please keep me and my family safe."

When I returned home at the end of the summer, I told my mother that I wanted to be christened. She said she didn't have a problem with it, and that I should think about choosing my godparents. When I broached the idea with my father, however, he was less than enthused. "I'm okay with it, but as I said before, it's going to mean going to church every Sunday morning."

So we were back to that! "Well, who is going to come with me?" I asked.

"Ask your mother, you know how I feel about this."

I didn't want to ask my mom. She had enough to do, what with working five days a week in addition to the housework and looking after us. I went off to think about what he'd said. I didn't know if I believed in God either, but there was no denying the experience. I felt transformed -- felt somehowlighter. I turned to my pocket Bible for some answers, but in a matter of days my interest in God and baptism and salvation began to wane. I was just a child, after all, and I guess I wasn't ready to give up my Sunday mornings.

Summer ended, and I started classes at Arrow Vale High School, where I began to think quite seriously about becoming a teacher, either in music or in physical education. My friend Sam was in the same school, but we drifted apart for a time because we were now in different classes. I was hanging out with three other girls -- Zoe, Lynn, and another Lisa -- and I was busy with music and sports. The psychic business was relegated to the background, but I still sensed things: A fight was about to break out in the schoolyard, a boy's father was going to die, a teacher would resign before the year was out.

In England, you can leave school at age sixteen; by then I had been at the school three years and all three of my new friends decided to leave. But I was determined to further my education and become a teacher, so I stayed on to do my A-levels, the exam necessary to qualify for university. Sam also stayed to do her A-levels, and I reconnected with her and another girl, called Andeline.

Out of the whole school, there were only about twenty of us studying for A-levels, and out of those twenty I was the only one pursuing music. One day, about a dozen of us were in the common room where we studied, and I slipped into the adjoining room to listen toDido and Aeneas, an opera by Purcell. I was wearing headphones, and I could see part of the common room through the glass partition. I could see the lounge area, with its mismatched sofas, and the desks beyond, where everyone was busy studying. There was a small kitchenette off to one side, with a refrigerator and a coffeemaker and a microwave, but it wasn't in my field of vision.

Fifteen or twenty minutes later, I heard a little voice in my head telling me to switch off the music and go see what happened, so I removed my headphones and walked into the common room. The kids were all staring at me, and two or three of them were as white as ghosts.

"What happened to the glass?" I asked, even though I had no idea what I was referring to. "Who broke it?"

Sam glanced in the direction of the kitchenette, which was off to the right, not visible from where I stood, then turned again to face me. I went closer and peered around the corner and saw broken glass all over the floor. "Well?" I said, turning again to face them.

Sam pointed toward my pencil case, which I'd left on one of the empty desks. "Andeline needed some Typex," she said. "I knew you had some in your pencil case, so we all decided to try to move it by using our minds. We focused on moving your pencil case with our minds."

One of the other girls piped up: "That's when a glass exploded in the kitchen."

"We were just having a bit of fun," one of the guys said, almost apologetically. "You know, on account of how you used to have the gift." They'd all heard about that, of course, and they all knew about my grandmother, and at that moment they were all looking at me as if I'd had something to do with the exploding glass -- something witchy.

"It's nothing," I said, acting as if I knew what I was talking about. "You created so much energy that the glass shattered. That's all."

They stared at me as if I had said something profound -- profound and more than a little scary. Then two of the girls went into the kitchenette and cleared up the glass, and we never spoke of it again.

At the end of the school year, a big group of us went off to Blackpool for a day, to celebrate. It's a beach town in the north of England, very popular with tourists. We partied and drank too much and had loads of fun, and then we returned to our respective homes and went our separate ways. Some of my classmates went off to university, but unfortunately, despite my hard work, I didn't have good enough grades, so I spent the first few weeks of summer wondering what I was going to do with the rest of my life.

In the weeks and months ahead, I managed to see a good deal of Airplane Nanny, Frances, the psychic one. She had been a heavy smoker much of her life, and by the time she quit the cigarettes had taken their toll, but she still had days when she seemed as healthy and as energetic as ever. From time to time, for example, she would jet off to France, Spain, Mexico, and America -- to "confer with clients," as she put it -- and she always returned with handfuls of foreign coins for me, which I began to collect. When she was home, the phone was always ringing off the hook with people calling for appointments -- she was so popular that she found it impossible to squeeze everybody in.

In fact, I'd often heard my mom talking to her friends about Frances's popularity. She said that she had once gone to a village fete, and that there had been a line of women around the block, desperate to have a reading with her. I remember being struck by this: that complete strangers would wait in line for hours for a chance to get a little advice and direction from my very own nan. I had no idea at the time that my life would soon take me in the same direction.

On those days when Nan was feeling under the weather, she'd put a hand-lettered sign on her front door that read: "Frances is not seeing anyone today. Please call back another day." People would knock anyway, and her son, Steven, who was living with her, had to drive them away. Uncle Steven was a nice man, but unfortunately had a drinking problem; Nan herself fancied the occasional drink. Whenever she traveled, she collected those little liquor bottles they used to sell on planes, and she always kept two or three in her purse so she could enjoy a little tot when she felt the need.

One day she caught me studying her Tarot cards, sitting in their usual place on the mantel. "What did I tell you about those!" she said. "You're not ready yet."

"I was just looking!" I said.

At that time, I had a part-time job as a waitress at the local golf club, where my dad had put in a good word for me, and shortly thereafter I took a second job at Graveneys, a sports shop in Redditch. On the occasional weekend, to get away, I'd borrow my mother's car and drive out to see my grandparents in Brean, and I'd spend the night with them in their caravan. That didn't last long, however, because I became friendly with Susan, one of the girls at Graveneys, and we discovered boys and nightclubs. At last, one of the joyous mysteries of life was revealed to me!

My parents were quite tolerant and would allow me to borrow the car as long as I had it back before Dad had to leave for work. Having access to the car gave me a wonderful sense of freedom, and many times I'd pull into the driveway after six a.m., cutting it fine. I'd run upstairs and jump into bed with all my clothes on, pretending to be asleep as if I had been there all night. I don't think I was fooling anyone. I'm sure they knew I had only just walked in, but they never said anything.

I would get as much sleep as I could, but I had to be out of bed by 8:30 to get to Redditch Town Centre, where I was now working full-time. Somehow I managed to survive on very little sleep, and the next night I was off to party all over again. But I was never late and I never missed work. I was very responsible.

Eventually, however, it all began to seem a little meaningless, and I decided that I really wanted to make something of my life. Without a proper degree, I would never become a school P.E. teacher, so I decided to do the next best thing and become a fitness instructor. I heard about an opening at the Pine Lodge Hotel, in Bromsgrove, the next town over, and I decided to take a drive out and pick up an application.

When I arrived I was quite impressed with the place. It had beautifully landscaped grounds, a fully equipped gym with state-of-the-art equipment, a large indoor pool, a sauna, and a steam room. When I subsequently went back for my interview, I was asked if I was a good swimmer, and I told them that I had in fact spent a summer qualifying as a swim instructor. That clinched it: The following week I gave notice at Graveney's, and the week after that I began at Pine Lodge.

Before long, I realized that I was in fact little more than a glorified cleaner. I'd assist members and hotel guests in the gym, posing as a personal trainer, and when there was no one around I arranged the changing rooms, emptied the laundry bins, and tidied up around the pool. I didn't mind it, though. I enjoyed meeting new people and having use of the gym. It had other advantages too. Before long I had made enough money to buy a car of my very own, a used Renault 19, a little four-cylinder job in a delightful faded gold color with matching interior. I loved it!

A few months into the job, I read an ad in the paper about a place in Trowbridge that was offering an intensive two-week course to qualify as an aerobics instructor. I sold the Renault at a surprising profit, even though I'd only had it for a short time, and bought a cheap Mini, brown in color. It was really zippy, so I took to calling it Chloe -- The Flying Turd. I used the extra money to pay for the course, and when I got back to the Pine Lodge I felt eminently more qualified to put everyone through their paces.

Throughout this period, I had tried to ignore my psychic feelings, but there were a lot of quiet moments at work, and it seemed as if the gift was trying to manifest itself. A woman would come into the gym, for example, and I would somehow sense that she'd had an argument with her boyfriend, and before long I'd have her talking about it. Once I had a dream in which the hotel pool was empty, and lo and behold, the next day there was a problem with the draining system, and the workmen had to empty it and fix it. And whenever I went to the laundry room to deposit the used towels, I could feel the presence of a man I sensed had died there more than a hundred years ago. I had a feeling that he wanted to talk to me, and that all I had to do was listen, but I didn't really want to hear what he had to say. I wasn't all that interested in pursuing myso-called gift; I was more interested in normal life.

One evening I was at a nightclub called Celebrities in Stratfordon-Avon, about twenty minutes from home, where I would dance all night and have my usual Diet Coke -- I never drank and didn't approve of drugs -- when I met Paul. He was six feet tall, with thick, dark hair and a slim, athletic body, and he was my first love. He worked as a chef at a beautiful hotel in the Cotswolds, but he had dreams of opening a place of his own someday, and I loved his energy and his ambition. I remember thinking,This is the man for me! I know it! I immediately fell for him.

I introduced him to my parents, who loved him too, and he introduced me to his, who were absolutely lovely. Everything about the relationship was perfect, and for the better part of a year we were completely intertwined in each other's lives. We only existed as a couple, and I dreamt of our life together in years to come.

That summer we were invited to the wedding of one of his cousins, and we were excited to go. But when we arrived, for some reason I started having strange feelings about our future, and I sensed that Paul was keeping something from me. I decided to ask him, "Are you okay? I feel you have something to tell me."

"What do you mean?"

"I just have a feeling that something's not right. What is it? You know you can tell me anything."

"Don't be silly," he said. "If I had something to tell you, I'd tell you."

I let it go, but the feeling grew stronger, and a few days later he called and asked me if I wanted to meet him that night for a drink. This was weird because it was a Wednesday and we never saw each other on Wednesdays as he worked late, but he explained he had the night off. I was happy, but nervous; I knew something wasn't right. I confided in my friend and told her that I was sure Paul had something to tell me and I wasn't going to like it.

She said, "Stop worrying. You and Paul are going to grow old and wrinkly together. You are made for each other!"

As much as I wanted to believe her, I started to dread the evening to come.

We met at our usual pub and had a great time. I was feeling much more relaxed and told myself I was being silly for having those feelings of anxiety. It was a lovely night and he suggested a walk by the river. How romantic, maybe he has something he wants to say...or ask, I thought, with a secret hope that he had a ring in his pocket.

We walked hand in hand until he stopped and gestured to a bench overlooking the river. He looked me in the eyes and said, "Lisa, you are right. I do have something to tell you. It's about work, and it has been the hardest decision I have ever had to make in my life."

It turned out he'd been offered another job, in another county, and he'd already accepted, and he didn't see me as part of the plan. I was devastated. I cried for a week. I was in such bad shape that I couldn't go to work. Mom called in sick for me.

"I felt so connected to him, Mom," I said, blubbering away. "I feel like part of me has been ripped away. I thought he loved me."

"I know, I know," she said, trying to comfort me. "But things like this happen for a reason, you'll feel better in time."

Dad tried to comfort me too. "It's another brick in life's wall," he said. "You will have these heartaches, but the experience will just make you a stronger person."

I thought I understood what he was saying, that it was all part of life's lessons, but I never wanted to go through it again. It hurt too much, and I promised myself I would never allow myself to be hurt like that again.

Copyright © 2008 by Lisa Williams

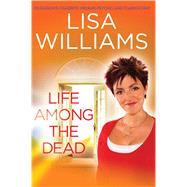

Excerpted from Life among the Dead by Lisa Williams

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.