Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Preface | p. xiii |

| Introduction: Independence Day, July 4, 1776 | p. 1 |

| From Friends to Rivals | p. 5 |

| Crossing the Bar | p. 37 |

| "Electioneering Has Already Begun" | p. 67 |

| Burr v. Hamilton | p. 87 |

| Caucuses and Calumny | p. 112 |

| A New Kind of Campaign | p. 138 |

| For God and Party | p. 164 |

| Insurrection | p. 190 |

| Thunderstruck | p. 213 |

| The Tie | p. 241 |

| Epilogue: Inauguration Day, March 4, 1801 | p. 271 |

| Notes | p. 277 |

| Index | p. 315 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

FROM FRIENDS TO RIVALS

Although the friendship between Adams and Jefferson took root in Philadelphia during the opening days of the American Revolution, it blossomed in Paris at war's end. Again, the scene included Franklin. For the scene in Philadelphia, John Trumbull created the enduring image of the trio in his monumental painting, The Declaration of Independence. They stood together, seemingly larger than life, at the focal point of attention amid a sea of delegates at the Continental Congress, their purposeful eyes gazing forward as if into the future. A war with Britain lay ahead, and the task of building a new nation.

They had changed by the time the war finally ended and they could begin building on the promise of peace. Already the oldest signer of the Declaration in 1776, Franklin was seventy-eight in 1784, stooped with gout and kidney stones, when Jefferson reached Paris to augment the American diplomatic delegation there. Shortly after declaring the nation's independence, Congress had dispatched Franklin to seek French support for the Revolution. Adams joined him in 1778 and, although Franklin had obtained an alliance with France by then, they worked together with a shifting array of American diplomats to secure loans from the Dutch, peace with Britain, and commercial treaties with other nations.

Of middling height and decidedly square shouldered, Adams had added to his girth on a diplomat's diet. Tall for his day, Jefferson had grown into his height by 1784 and typically held himself more upright than before. When the three patriot leaders reunited as diplomats in Paris, the physical contrast between them had become almost comical. Upon making their initial joint appearance at the royal court in Versailles, one bemused observer likened them to a cannonball, a teapot, and a candlestick. America, however, never enjoyed abler representation in a foreign capital.

Franklin arrived in France already a celebrity and enhanced his reputation further while there. Hailed as the Newton of his day for his discoveries in electricity and renowned also as an inventor, writer, practical philosopher, and statesman, Franklin vied only with Voltaire as the public face of the Enlightenment, which then dominated French culture and influenced thought throughout Europe and America. When the two senior savants embraced at a public meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in 1778, it seemed as if all Europe cheered -- or so Adams reported with evident envy. "Qu'il etoit charmant," he caustically commented in two languages. "How charming it was!"

The sage of Philadelphia became a fixture in the finest salons of Paris and continued his scientific studies even as he served as America's senior diplomat in Europe. Ladies of the court particularly favored him, and he them, which gave Franklin access to the inner workings of pre-Revolutionary French society. These activities complemented each other by reinforcing Franklin's already legendary stature. Born in poverty on the edge of civilization and content to play the part of an American rustic by wearing a bearskin cap in fashion-conscious Paris, Franklin received honors and tributes from across Europe. A gifted diplomat, he secured what America needed from France to win the Revolution and secure its independence.

While in France, Adams always served in Franklin's shadow. At first, he accepted the shade. "The attention of the court seems most to Franklin, and no wonder. His long and great reputation...[is] enough to account for this," Adams wrote during his first year in Paris. Adding to his aggravation, however, was that Europeans seemingly took pains to distinguish him from his better-known cousin, the revolutionary firebrand Samuel Adams. "It was a settled point at Paris and in the English newspapers that I was not the famous Adams," the proud New Englander complained, "and therefore the consequence was settled absolutely and unalterably that I was a man of whom nobody ever heard before, a perfect cipher."

Gradually, Adams turned his rancor on Franklin, which soured their relationship. Except for John Jay (who joined them in negotiating peace with Britain), prior to Jefferson none of the diplomats sent by Congress to work with Franklin and Adams could bridge the growing divide. "The life of Mr. Franklin was a scene of continued dissipation. I could never obtain the favor of his company," Adams observed bitterly. "It was late when he breakfasted, and as soon as breakfast was over, a crowd of carriages came to his...lodgings, with all sorts of people: some philosophers, academicians, and economists...but by far the greater part were women and children who came to see the great Franklin." Then came formal dinners, parties, and concerts. "I should have been happy to have done all the business, or rather all the drudgery, if I could have been favored with a few moments in a day to receive his advice," Adams complained, "but this condescension was not attainable." Yet, Franklin managed a triumph at every turn despite (or perhaps because of) his socializing, which rankled the Puritan in Adams.

The only respite came in 1779 when, after Franklin secured the alliance with France and became America's sole ambassador to the French court, Adams returned to Massachusetts. He was back in Europe before year's end, however, assigned to work with Franklin and Jay in negotiating peace with Britain.

Despite their animosities, Franklin and Adams labored on with amazing success, each putting his nation's interests above his own. Always blunt and sometimes explosive, Adams was an unnatural diplomat at best. The odd-couple blend of Franklin's tact and Adams's tirades produced results. The alliance with France held, Britain conceded a generous peace, and America gained and maintained its independence from both of those grasping world powers. Between the two men, however, their personal relationship never recovered. Franklin's characterization of Adams stuck to him like tar and stained him forever: "Always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes, in some things, absolutely out of his senses."

Both men rejoiced in 1784 when Jefferson arrived in Paris to join them in seeking postwar treaties of commerce and friendship with the various European nations. For Franklin, the attraction was obvious. A scientist and philosopher in his own right, Jefferson shared Franklin's Enlightenment values and religious beliefs. As fellow Deists, they acknowledged a divine Creator but, as Jefferson once wrote, they trusted in "the sufficiency of human reason for the care of human affairs." If they prayed for anything from God, it was for wisdom to seek answers rather than for the answers themselves. Better yet for their relationship, Jefferson accepted Franklin's greatness without a trace of envy. In 1785, when Congress granted Franklin's longstanding request to retire and tapped Jefferson to serve as America's ambassador in Paris, the Virginian stressed that he would merely succeed Franklin: No one could replace him.

Adams seemed as happy as Franklin to receive Jefferson. His "appointment gives me great pleasure," Adams exulted at the time. "He is an old friend...in whose abilities and steadiness I always found great cause to confide." Best of all for Adams, Jefferson readily deferred to him and treated him as a senior colleague. "Jefferson is an excellent hand," Adams soon wrote. "He appears to me to be infected with no party passions or natural prejudices or any partialities but for his own country." Adams highly valued these traits. He accepted a political hierarchy founded on talent and believed in disinterested service by the elite. Jefferson seemed to exemplify these characteristics. Adams now spoke of the "utmost harmony" that reigned within the American delegation. "My new partner is an old friend and coadjutor whose character I studied nine or ten years ago, and which I do not perceive to be altered. The same industry, integrity, and talents remain without diminution," Adams observed.

Although Adams may not have noticed it at first, Jefferson had, however, changed. He now carried his height with dignity and hid his insecurities behind an ever more inscrutable facade. Never as self-confident as Adams, Jefferson learned to ignore the type of slights that often enraged Adams. In 1776, frustrations with public life and concerns about his wife's health led Jefferson to resign from Congress and decline appointment as a commissioner to France. He needed time at his beloved Monticello plantation. Once home, Jefferson reclaimed his seat in the Virginia legislature; worked to reform state laws to foster such republican values as voting and property rights, the separation of church and state, and public education; and served two troubled one-year terms as governor during the darkest days of the Revolution. After his wife, Martha, died following a difficult childbirth in 1782, Jefferson agreed once more to represent Virginia in Congress and, two years later, accepted the renewed offer to represent America in Paris. With his wife gone, he needed to leave Monticello as much as he once needed to be there. He grieved for her greatly and kept the vow purportedly made by him to her on her deathbed never to remarry.

During the week that Jefferson arrived, Adams's wife and three younger children joined Adams and their two older children in Paris after five painful years of separation. The Adamses welcomed the lonely Virginian into their happy home. For Jefferson, Abigail Adams became a trusted source of personal and family advice from a woman who was his intellectual equal. She also took Jefferson's two surviving children under her wing at times. He reciprocated in a manner that led John Adams to comment later to Jefferson that, in Paris, young John Quincy "appeared to me to be almost as much your boy as mine." Upon Adams's departure from Paris in 1785 to become the first American ambassador to Britain, Abigail expressed her regret about leaving Jefferson, whom she described as "the only person with whom my companion could associate with perfect freedom and unreserve." To Adams, Jefferson wrote, "The departure of your family has left me in the dumps. My afternoons hang heavy on me."

With both Franklin and Adams gone, however, Jefferson came into his own as the leading American diplomat on the European continent. Immersing himself in French culture as Adams never did, he became attached to the French people and hoped for their freedom from monarchic despotism and Catholic clericalism. "I do love this people with all my heart and think that with a better religion and a better form of government...their condition and country would be most enviable," Jefferson wrote to Abigail Adams in 1785. The French royals, personified for some by the debauched queen Marie Antoinette, and many French aristocrats and church leaders lived in splendid isolation from the grinding poverty of the forgotten masses.

For a time, the friendship between Adams and Jefferson survived their separation. In 1787, for example, after Jefferson's closest political ally and confidant in Virginia, James Madison, questioned Adams's character, Jefferson (while conceding Adams's vanity and irritability) replied, "He is so amiable that I pronounce you will love him if ever you become acquainted with him." Two years later, Adams concluded a letter to Jefferson with the words, "I am with an affection that can never die, your friend and servant." At heart, however, it was a friendship between political allies fixed in time and place.

In both Philadelphia and Paris, Adams and Jefferson represented similar or the same interests far from home, and did so with extraordinary passion and ability. This united them. As their political goals for America diverged, however, their ideological zeal drove them apart. These were serious, ambitious men with deep beliefs and grand ideas. Whenever and wherever their paths crossed, Adams and Jefferson were destined to become either fast friends or formidable foes.

During their early lives in the mid-1700s, no one could have guessed that the paths of Adams and Jefferson would ever cross -- much less assume overlapping courses during the late 1700s and then collide in 1800. Prior to the coming of the American Revolution, the northern and southern colonies might as well have occupied separate continents. A Virginian and a New Englander -- even two such cosmopolitan lawyers as Adams and Jefferson -- would have little occasion to meet each other, except perhaps in London on imperial business. Instead they met in Philadelphia at the Second Continental Congress in 1775 with the shared goal of freeing the colonies from Britain's yoke. Their ambitions for themselves and their new nation became the basis for their special friendship.

Ambition marked these men. Both were the first sons in rising families at a time when social custom and inheritance law placed special opportunities and obligations on the eldest male heir. Jefferson's industrious father had greatly expanded the family's land and slave holdings in central Virginia, and passed them to his eldest boy along with a lively intellect, a craving for material possessions, and a fierce streak of independent self-reliance. Adams's father was also driven, but in a pious Puritan sense that pushed him to expand his modest Massachusetts farm, accept positions of trust within his local church and community, and sacrifice to send his firstborn son to Harvard College with a hope that, through formal education, the son could outshine the father in every good and virtuous endeavor. Like his father, Adams tried to live well within his means. Indeed, he enjoyed nothing more than being with his family and smoking a good cigar, both of which he did as often as he could.

Adams and Jefferson drank in their fathers' ambitions and made them their own. "Reputation ought to be the perpetual subject of my thoughts, and the aim of my behavior," Adams chided himself in his diary while still a young lawyer in 1759. He soon wrote to a friend, "I am not ashamed to own that a prospect of an immortality in the memories of all the worthy to [the] end of time would be a high gratification to my wishes." To achieve this goal, he devoted himself to study far beyond the requirements of his profession. Indeed, few colonists of his day could boast of as deep or broad a legal education as Adams's -- except perhaps Thomas Jefferson.

At the College of William and Mary, Jefferson chose study over social life in a manner wholly foreign to the convivial spirit of that place as a finishing school for the planter elite. He "could tear himself away from his dearest friends and fly to his studies," one classmate recalled. Others estimated that Jefferson worked fifteen hours a day. He wanted to learn the law, Jefferson admitted, so that he would "be admired." Simply becoming a lawyer and planter was not enough, however, because he continued his bookish studies long after passing the bar and inheriting his father's plantation. Indeed, in 1767, he counseled a young lawyer about the "advantage" of ongoing study, and recommended reading science and theology before breakfast; the law during the forenoon; politics at lunch; history in the afternoon; and literature, criticism, and rhetoric "from dark to bedtime." Jefferson imposed just such a regimen on himself as a young lawyer and continued a disciplined program of self-education throughout his long life. "Determine never to be idle. No person will have occasion to complain of want of time who never loses any. It is wonderful how much may be done if we are always doing," he wrote to his daughter Martha in 1787. "A mind always employed is always happy."

As young lawyers, the greatest challenge faced by Adams and Jefferson lay in gaining sufficient scope for their ambitions. No American colony could provide a suitable stage to display their talents, and the British Empire offered only bit parts to colonial actors. Thinking back in later life about their prospects as ambitious young men, both Adams and Jefferson recalled that initially they could conceive of no higher positions for themselves than appointment to the King's Council (or senate) for their respective colonies. Perhaps that fed their disillusionment with the imperial regime. They wanted so much more than the King would allow his colonists.

Vain to a fault, Adams never hid his ambitions. In 1760, for example, before the first stirrings of the American Revolution, he wrote prophetically to a friend, "When heaven designs an extraordinary character, one that shall distinguish his path thro' the world by any great effects, it never fails to furnish the proper means and opportunities; but the common herd of mankind, who are to be born and eat and sleep and die, and be forgotten, is thrown into the world as it were at random."Adams saw himself in the former class -- as did Jefferson -- but colonial America could not offer him a "proper means" to glory. Not content with waiting upon heaven to supply the means, Adams examined his options. "How shall I gain reputation?" he wrote in a 1759 diary entry. Shall I patiently build my law practice or "shall I look out for a cause to speak to, and exert all the soul and all the body I own to cut a flash...? In short shall I walk a lingering, heavy pace or shall I take one bold determined leap?" He chose to leap.

In 1765, new stamp taxes on newspapers and other printed matter imposed by Britain solely on American colonists gave Adams his first chance to attach himself to a larger cause. He began testing his revolutionary rhetoric by denouncing the new taxes as "fabricated by the British Parliament for battering down all the rights and liberties in America." This assault appeared in Adams's private diary, however. Although he met frequently with patriot leaders and drafted stern instructions from his town to the colonial legislature condemning "taxation without representation," Adams mostly pulled his punches in public or published his words anonymously, perhaps in part to protect his growing legal practice. When Britain repealed the repressive levy in response to widespread colonial protests, Adams envied the glory heaped upon more-visible patriots, including his fiery cousin Samuel.

By the time of the Townshend Duties crisis in 1768, which erupted after Britain imposed added tariffs on American imports, Adams wrote privately that his legal career "will neither lead me to fame, fortune, [or] power, nor to the service of my friends, clients or country." Determined to make his mark, increasingly he became the public leader of the patriot cause in Massachusetts through his writings, speeches, and government service. He became an early advocate of independence at a time when most Americans still thought that they could work out their differences with Britain amicably. In comparison with his public service, the private practice of law became a "desultory life" for Adams: he called it "dull," "tedious," and "irksome."

Jefferson gradually reached the same conclusion as Adams about the law and his career. He privately dismissed legal literature as "mere jargon" as early as 1763 and abandoned his law practice altogether in 1774, after receiving a sizable inheritance following his father-in-law's death. Almost immediately, Jefferson emerged within the Virginia colonial legislature as a prominent critic of British rule. He had a bearing and intellectual depth that commanded respect -- even awe.

Drawing on their years of training and practice, Adams and Jefferson turned from defending private clients to prosecuting the American Revolution. They had found their path to glory and a stage equal to their ambitions and abilities: the United States of America.

Adams went to the First Continental Congress in 1774 as a committed proponent of independence. Jefferson joined him a year later at the Second Continental Congress, which met continously during the American Revolution. They shared a resolve to break with the mother country, making them staunch allies. Their kindred spirits -- at once philosophical and practical -- also made them friends who could converse and conspire in confidence. In Congress, both men quickly gained the respect and influence that naturally flows to members with firm convictions, superior intelligence, and an ability to persuade others. Although Jefferson spoke little in formal sessions of Congress, Adams recalled that from their first encounters he found the Virginian "so prompt, frank, explicit, and decisive upon committees and in conversation...that he soon won my heart" -- almost like a younger brother or an adult son.

Together, they pushed and prodded their fellow delegates to accept the inevitability of independence. First, Congress adopted as its own the New England militia besieging the British army in Boston following the battles of Lexington and Concord. Then Adams led the effort to further nationalize these patriot troops by placing George Washington, a Virginian, in overall command. Finally, after the five-member drafting committee delegated the job of crafting the Declaration of Independence to the two men, Adams asked Jefferson to pen the first draft -- again hoping to bind the South to the patriot cause.

The Virginian succeeded brilliantly in that task: "We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal and independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & unalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these ends, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government shall become destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it." Although the committee and Congress made various changes to Jefferson's text, the soaring words and lyrical structure survived. Adams could not have written a first draft more suited to his views. Indeed, the visionary affirmation that "all men are created equal" sounded more like the words of a Massachusetts Puritan than those of a Virginia slaveholder. The expansive "pursuit of happiness" passage, however, was pure Jefferson. The British political philosopher John Locke had spoken of natural rights to life, liberty, and property; but the pursuit of happiness struck Jefferson as so much nobler than simply the acquisition of property, even though Jefferson himself had an insatiable appetite for physical possessions. Indeed, Jefferson's words often soared beyond his actions, leading to enigmatic inconsistencies in his personality that some saw as hypocritical.

Their work together in Philadelphia for a declaration of independence had scarcely ended when Adams and Jefferson parted company. In September 1776, Jefferson left Congress to be with his ailing wife and young children in Virginia. There, he threw himself into efforts to liberalize the state's aristocratic legal code and to end state support for the Anglican Church. He declined the first summons from Congress to serve with Franklin in France, writing to the senior statesman in 1777, "I wish my domestic situation had rendered it possible for me to have joined you in the very honorable charge confided to you." Jefferson fully appreciated the importance of that charge: Securing French support for America's revolution would likely decide the war's outcome. After refusing that call, Adams begged Jefferson to return to Congress. "We want your industry and abilities here extremely," he wrote in May 1777. "Your country is not yet quite secure enough to excuse your retreat to the delights of domestic life." Still, Jefferson remained at home.

Adams ultimately served in France in Jefferson's stead, arriving after Franklin had secured the needed military alliance. Jefferson joined them there in 1784. After Franklin returned home in 1785, for the next three years, Adams served in London and Jefferson in Paris as America's two ranking foreign diplomats. It was a particularly difficult time to serve the country abroad. America had secured its political independence with the signing in 1783 of a peace treaty with Britain. Under the Articles of Confederation, the country remained a loose confederation of states, however, until ratification of the Constitution in 1788. Without an effective national government to represent, Adams and Jefferson could accomplish little. Although they secured a critically needed loan from Dutch bankers, Britain refused to honor its treaty obligation with the United States to evacuate its forts in the Great Lakes region, and France descended toward revolutionary turmoil. After generations of oppression and with the government on the verge of bankruptcy, the people of France arose against their leaders with unexpected violence. Tensions continued between the United States and its former colonial master; America's recent ally, France, could no longer offer any effective assistance. America stood alone in a hostile world and neither Adams nor Jefferson could do much about it as ambassadors.

From their posts in Europe, they watched during 1787-88 as delegates to the Constitutional Convention framed and the states ratified the new national charter. Success remained in doubt until the end. Concerns over representation in Congress divided the small and large states; the issue of slavery already split North from South. The Convention repeatedly bogged down in factional strife and the ratification process became highly contentious in some states.

Concerns about the document reached Americans in Europe and were avidly debated there. Jefferson feared that the Constitution gave too much power to the President, who was chosen by electors; Adams worried that it gave too much power to the Senate, whose members were appointed by the state legislatures. Both thought that it should include a bill of rights. "You are afraid of the one -- I, the few," Adams wrote to Jefferson in 1787. "We agree perfectly that the many should have full, fair, and perfect representation. You are apprehensive of monarchy; I, of aristocracy."

Despite their reservations about the compromise document that emerged from the divided Convention, Adams urged that Massachusetts ratify it while Jefferson expressed his qualified support for ratification in Virginia. Having seen what he perceived as the benefits of strong monarchies in Europe, Adams thought that only an effective central government led by a powerful president could forge a stable, secure nation from a multitude of weak, wrangling states. He supported the new Constitution as a means toward that end and thereby gained prominence among those proponents of ratification and a strong national government who called themselves Federalists. Jefferson, in contrast, saw representative democracy and states' rights as the bulwarks of liberty, as against the potential corruption and tyranny of a powerful executive, and he stressed those aspects of the new constitutional union. Although Jefferson did not oppose ratification, he became a leading voice within the faction that included both Anti-Federalists, who had opposed ratification, and more moderate critics of a strong national government. Collectively, its members became known as Republicans or, later, Democrats. These differences in emphasis and constitutional interpretation between Adams and Jefferson sharpened as the government took shape following ratification.

As patriot leaders representing differing factions within the broad constitutional consensus, both men returned to America and took leadership positions in the new government. Serving under President Washington, Adams was elected Vice President and Jefferson was named Secretary of State. Together with others, they endeavored to form a unity government embracing a broad spectrum of federalist-republican opinion. They were convinced that well-meaning leaders could draw together in establishing the union just as they had once united to fight for independence.

Based on their wartime experience of suppressing political differences for the common good, the new government's leaders uniformly condemned factionalism and opposed the formation of political parties. Individuals in Congress and the executive branch should address each issue on its merits, they thought, rather than take partisan positions. For this reason, despite their growing differences, Adams and Jefferson tried to get along. Upon hearing of Adams's election as Vice President, Jefferson warmly congratulated him, "No man on earth pays more cordial homage to your worth nor wishes more fervently your happiness." Adams, in turn, hailed Jefferson's appointment as the first Secretary of State.

The differences dividing Adams and Jefferson reflected a deepening ideological rift that divided mainstream Americans into factions. As the nascent government took shape under the Constitution, the people and their chosen representatives vigorously debated various issues regarding the authority of the national government and the balance of power among its branches and between it and the states. Whether the national government could charter a bank and thus create a national banking system became especially heated, for example. Many doubted if the new national government would long survive. Adams and those calling themselves Federalists saw a strong central government led by a powerful president as vital for a prosperous, secure nation. Extremists in this camp, like Alexander Hamilton, who favored transferring virtually all power to the national government and consolidating it in a strong executive and aristocratic Senate, became known as the ultra or High Federalists. At the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton had unabashedly depicted the monarchical British government as "the best in the world" and famously proposed life tenure for the United States President and senators.

Jefferson and his emerging Republican faction viewed such thinking as inimical to freedom. A devotee of enlightenment science, which emphasized reason and natural law over revelation and authoritarian regimes, Jefferson trusted popular rule and distrusted elite institutions. Indeed, like French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau, Jefferson instinctively revered man in nature. "Those who labor in the earth," such as farmers and frontiersmen, possess "substantial and genuine virtue," he wrote in his 1787 book, Notes on the State of Virginia. "The will of the majority, the natural law of every society, is the only sure guardian of the rights of men," Jefferson affirmed three years later. He instinctively favored the people over any institution.

In contrast, Adams and the Federalists tended to distrust the common people and instead to place their faith in the empowerment of what they saw as a natural aristocracy, though one that should be restrained by civil institutions such as those provided by a written constitution with checks and balances. "The voice of the people has been said to be the voice of God, and however generally this maxim has been quoted and believed, it is not true," Hamilton reportedly told the Constitutional Convention regarding a popularly elected legislature. "The people are turbulent and changing; they seldom judge or determine right. Give therefore to the first [or upper house] a distinct, permanent share in the government. They will check the unsteadiness of the second [or lower house]."

Although more moderate in his Federalism than Hamilton, but still unlike the Republican Jefferson, Adams thought that every nation needed a single, strong leader who could rise above and control self-interested factions of all classes and types. Neither an aristocratic Senate nor a democratic House of Representatives would safeguard individual rights, he believed. Indeed, Adams once complained to Jefferson about "the avarice, the unbounded ambition, [and] the unfeeling cruelty of a majority of those (in all nations) who are allowed an aristocratic influence; and...the stupidity with which the more numerous multitude not only become their dupes but even love to be taken in by their tricks." Only a disinterested chief executive -- the fabled philosopher-king of old -- would protect liberty and justice for all. Adams thus combined a Calvinist view of humanity's innate sinfulness with an Old Testament faith that a Moses-like leader could guide even such a fallen people through the wilderness into the promised land of freedom.

Due to these beliefs, Adams supported a strong American presidency. Although Adams always preferred an elected supreme leader to a hereditary one, his thinking leaned too much toward monarchism for Jefferson to stomach, especially when others in positions of power around Adams, most notably Alexander Hamilton, openly praised the "balanced" British constitution with its hereditary House of Lords, representative House of Commons, and still-powerful king. As Washington's Treasury Secretary, Hamilton pushed a centralizing, probusiness program of internal taxes, protective tariffs, a national bank, and close trading ties with Britain. He viewed them as essential for national power, prestige, and prosperity.

Jefferson opposed all these policies as destructive of individual liberty and equality of opportunity. Even more, he feared that they would undermine popular rule by creating an aristocracy of wealth in America, a homegrown elite. He did not want the United States simply to become a better Britain, with its concentrated wealth and power. He dreamed of something new under the sun in America -- a land of free, prosperous farmers and workers. His support for their rights was staunch and heartfelt.

The differences between Adams and Jefferson became clear in their responses to Shays's Rebellion, a widely publicized antigovernment protest in Adams's home state of Massachusetts. In 1786, hundreds of western Massachusetts farmers led by Revolutionary War officer Daniel Shays briefly took arms against high taxes and strict foreclosure laws during the economic recession that followed the American Revolution. Massive deflation threatened these protesters with the loss of their property and jobs, while the state government only made matters worse for them by raising taxes to repay bondholders for Revolutionary Era debts.

When news of the uprising reached him in Paris, Jefferson used a metaphor from science to convey his reaction in a letter to Abigail Adams, who was then in London with her husband. "I like a little revolution now and then. It is like a storm in the atmosphere," Jefferson wrote. She was horrified. Speaking for herself and probably her husband, she told Jefferson her views on Shays's Rebellion in no uncertain terms: "Ignorant, restless desperados, without conscience or principles, have led a deluded multitude to follow their standard under pretense of grievances which have no existence but in their imaginations."

Jefferson came to see the episode as significant. From his post in London, John Adams did not sufficiently appreciate the protesters' dire plight, Jefferson later wrote. He feared that Adams took the uprising to mean that even "the absence of want and oppression was not a sufficient guarantee of order" against popular revolts stirred by a demagogue. This disagreement over Shays's Rebellion, however mild it seemed at the time, began to fray the relationship between Jefferson and the Adamses; it was a foretaste of the bitter divisions to come.

The divisions between Adams and Jefferson were exasperated by the more extreme views expressed by some of their partisans, particularly the High Federalists led by Hamilton on what was becoming known as the political right, and the so-called democratic wing of the Republican Party on the left, associated with New York Governor George Clinton and Pennsylvania legislator Albert Gallatin, among others. Proud of his humble origins, Adams always had reservations about Hamilton's elitist agenda. He particularly questioned the wisdom of a national bank and never warmed to Britain. Those reservations were lost on Jefferson, however, who reacted against the whole and all of its parts. Adams supported the basic outlines of the Federalist program, and Jefferson resented it. By 1792, Madison, who always acted on Jefferson's behalf in such matters, was calling for a "Republican" party to oppose Hamilton and the Federalists. For his part, Adams never thought Jefferson did enough to restrain the extreme democrats among his supporters. On both sides, the outlines of party organizations emerged in the rise of partisan newspapers, the coordination of voting by members of Congress, and party endorsements for political candidates.

Washington and Adams were not the primary targets of the Republicans, but they came under fire to the extent that they supported Hamilton's projects. The Republicans embraced policies that favored popular sovereignty, individual freedoms, low taxes, farms over factories, and a limited national government. During the next three decades, the party's name would evolve from Republican into Democratic, leaving the former label for a later, indirect descendant of the Federalist faction.

Adams's actions as Vice President unwittingly further fed Jefferson's fears that the Federalists would subvert democracy. In 1789, Adams urged Congress to confer a "regal" title on the President, such as "His Most Benign Highness" or (better yet) simply "Majesty," which Jefferson dismissed as "the most superlatively ridiculous thing I ever heard of." Expressing his republican sentiments, Jefferson added, "I hope the terms of Excellency, Honor, Worship, [and] Esquire forever disappear from among us."

Then, in 1790-91, Adams published Discourses on Davila, a series of historical essays warning against the dangers of human passion and unchecked democracy. They raised Adams's standing with High Federalists but lowered it among Republicans. In the final essay, he attributed the persistence of monarchism in "almost all the nations on the earth" to the failings of popular rule. "They had tried all possible experiments of elections of governors and senates," Adams wrote, but found "so many rivalries among the principal men, such divisions, confusions, and miseries, that they had almost unanimously been convinced that hereditary succession was attended with fewer evils than frequent elections." Adams's words seemed to support a British-type system in which only the legislative lower house was elected. Certainly Jefferson read them that way. "Mr. Adams had originally been a republican," Jefferson later wrote. "The glare of royalty and nobility, during his mission to England, had made him believe their fascination a necessary ingredient in government."

Jefferson engaged Adams privately about the essays, freely calling him a "heretic" to his face for the antirepublican sentiments expressed in them. A strong presidency, independent of checks imposed by the elected House of Representatives, inevitably threatened democracy, Jefferson argued, especially if the President took on regal airs. A hereditary monarch was much worse. Adams maintained that the essays simply chronicled the European experience; they did not endorse an American king.

The dispute went public when Thomas Paine's blistering defense of radical democracy in revolutionary France, The Rights of Man, appeared in the United States in April 1791. It bore an endorsement from Jefferson expressing his pleasure "that something is at length to be publicly said against the political heresies which have sprung up among us." Politicians read Jefferson's words as a direct assault on Adams's Davila, which they were.

A published attack by the Secretary of State on the Vice President threatened to split the administration and clearly irritated Washington. Jefferson apologized for the public affront by saying that he never intended or expected his endorsement to appear in print. Of course "I had in my view Discourses on Davila" and Adams's "apostasy to hereditary monarchy and nobility," Jefferson explained in a letter to the President, "but I am sincerely mortified to be thus brought forward on the public stage." To Adams, Jefferson wrote, "That you and I differ in our ideas of the best form of government is well known to both of us; but we have differed as friends should do, respecting the purity of each other's motives and confining our differences of opinion to private conversation."

In his response, Adams formally accepted Jefferson's apology but protested that the damage to his reputation had already been done. "The friendship which has subsisted for fifteen years between us without the slightest interruption, and until this occasion without the slightest suspicion, ever has been and still is very dear to my heart," Adams wrote. In fact, it was all but over. The longtime friends had become political rivals.

During the early 1790s, a raging and widespread war between royalists and republicans in Europe greatly intensified these partisan tensions in America, which further strained the relationship between Adams and Jefferson. The European war had its roots in the violent fall of the monarchy and rise of republican rule in France, which sent tremors through the royal houses of Europe. France's absolutist ancien régime began to totter in 1788 with the calling of a legislative assembly for the first time in over 150 years. Every French king since Louis XIV had claimed absolute power, but an unprecedented financial crisis, caused in part by helping to fund the American Revolution, forced Louis XVI to convene the old Estates General in order to obtain its consent to raise new taxes. This body consisted of three branches -- one each for nobles, clerics, and commoners -- with the consent of all three needed to institute any meaningful reforms. The commoners had distinct grievances against the government, however, with the largely disenfranchised masses suffering under heavy taxes and often living in abject poverty following a series of poor harvests.

Soon after it convened, the commoners' Third Estate declared itself the sole legislative authority in France and, absorbing the other two estates, renamed itself the National Assembly. At first, members of the other two estates resisted, but violent protests in support of the commoners and the threat of a nationwide popular insurrection forced the nobles, the clerics, and the King to comply. The army could not control the protesters, and in some places actually sided with the people. A revolution was clearly under way even if the extent of it remained in doubt. The King had lost his claim to absolute power and many sensed that the nobility and established church were vulnerable as well. Ineptly, Louis XVI began playing the various sides against the others in an effort to survive as a limited monarch.

On hand as the American ambassador in Paris, Jefferson welcomed these developments despite the worsening violence. "The revolution of France has gone on with the most unexampled success hitherto," he blithely wrote to Madison in May 1789, after hundreds had died in mass protests and military reactions in Paris and other cities. Countless thousands more were dying from starvation and disease as the economy collapsed under the stress of political disorder and repeated poor harvests. Some of the riots started out as nothing more than mass cries for food from government granaries, then ended in slaughter as troops attacked and protesters reacted. The Queen's alleged response to the masses pleading for bread, "let them eat cake," would seal her fate. She never uttered the famous phrase, but it fit her popular image and rumors that she said it circulated widely at the time.

Jefferson remained in Paris long enough to witness the fall of the royal Bastille prison to the revolutionaries on July 14, 1789. "They took all the arms, discharged the prisoners, and...carried the [prison's] governor and lieutenant governor to the Greve (the place of public execution), cut off their heads, and set them through the city in triumph," Jefferson wrote excitedly in his official report. "The decapitation of [Governor] de Launai worked powerfully thro' the night on the whole aristocratical party insomuch that in the morning those of the greatest influence...[accepted] the absolute necessity that the king should give up everything."

Impressed by this popular uprising, Jefferson contributed to the fund for the families of those slain storming the Bastille. He naïvely predicted that a constitutional monarchy respecting individual rights would quickly emerge from the ashes of absolutist rule. Jefferson believed that nobles and clerics would readily relinquish power to the people, and he personally urged his friends in the aristocracy to do so.

Viewing events through the lens of the American Revolution, Jefferson saw only better times ahead for France. "We cannot suppose this paroxysm confined to Paris alone," he noted. "The whole country must pass successively thro' it, and happy if they get thro' it as soon and as well as Paris has done." To Madison, Jefferson added, "This scene is too interesting to be left at present." His daughters had grown, however, and he wanted to take them home. Upon arriving with them in America late in 1789, and still planning to return to France without them, he learned that Washington had named him the first Secretary of State. Jefferson never again left the country.

As Secretary of State, Jefferson continued steadfastly to side with the revolutionaries in France even as violence there spiraled out of control. Priests were massacred or driven from the realm for their loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church; nobles fled too, and their property was confiscated; protesters fell by the thousands in military reactions. In 1792, partisans pulled Jefferson's friend, the reform-minded Duc de La Rochefoucauld, from his coach and killed him in full view of his mother and wife. Nevertheless, in 1793, Jefferson wrote of the revolution in France, "The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should fail, I would have seen half the earth desolated." He saw the scene much like the English romantic poet William Wordsworth depicted it: "France standing on the top of golden hours / And human nature seeming born again." It was a bloody birth.

In contrast, the events in France horrified Federalists in the United States. Growing ever more radical and powerful, the French National Assembly (reconstituting itself first as the Legislative Assembly and then as the Convention under successive constitutions) took command of the armed forces, nationalized the Church, abolished noble titles and privileges, and made the King virtually its prisoner, holed up and under growing threat first at Versailles and then, by the Assembly's command, at the Tuileries Palace in Paris. Of the Assembly and its impact on France, Hamilton wrote, "It has served as the engine to subvert all her ancient institutions, civil and religious, with all the checks that served to mitigate the rigor of authority." Royalist regimes in Europe led by Prussia and Austria responded to these developments by invading France in 1791 to restore the old order. The invasion served only to radicalize the Assembly still further and precipitate a vicious counterattack. The French people rallied to defend their nation even if they did not otherwise support the revolution.

After riding the whirlwind of revolution for four years, Louis XVI fell from his increasingly titular post as King after fleeing the besieged Tuileries Palace on August 10, 1792, paving the way for the Convention to impose republican rule on France six weeks later. Citizen Louis Capet, as the revolutionaries delighted in calling the former King, was imprisoned in the Temple fortress by the radical Paris Commune along with his widely despised wife, Marie Antoinette. "I'll tell you what," John Adams reportedly commented, "the French republic will not last three months." Although proved wrong, Adams's prediction surely expressed the hopes of many in his party, some of whom favored revising the Constitution to provide a constitutional monarchy for the United States.

Inspired by republican visions of liberty, equality, and fraternity, the French armies pushed back invading royalist forces and began spreading democracy to neighboring lands at gunpoint. "On this day began a new era in the history of the world," German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously wrote after watching French republican forces rout Prussian imperial troops at Valmy, in France, on September 20, 1792. After he heard of the battle, Jefferson exulted, "Our news from France continues to be good, and promises a continuance; the [extent] of the revolution there is now little doubted of, even by its enemies."

Jefferson had hardly written these words before the Convention tried and guillotined the former King, closed Christian churches, and conscripted the entire population into the war effort. Although the revolutionary government had already nationalized the Catholic Church in France and deported or killed priests who would not swear their allegiance to the new order, radicals in the Convention still feared churches as rallying points for reactionaries. Soon the former Queen followed her husband to the scaffold. A new constitution proposed limiting private property and enshrining the right of revolution. By mid-1793, the Convention's most radical faction, the Jacobins, assumed control. Pressed by opponents from within and without, Jacobins instituted a Reign of Terror to purge France of counterrevolutionaries. Thousands died in public executions, often on mere suspicion of disloyalty, including many of the leading revolutionaries themselves.

The differing views of Federalists and Republicans in America regarding the bloody course of events in France made any attempt at nonpartisan governance by the Washington administration virtually futile. Bitter domestic disputes over national power, informed as they now were by analogies to the affairs in Europe, worsened the situation. By the end of Washington's first term in 1793, the unity government that he had so carefully assembled lay in shambles. Jefferson and Hamilton fought privately for influence within the administration while their respective factions battled openly in Congress and the press. As Vice President, Adams played virtually no part in executive-branch deliberations and was silenced in the Senate, over which he presided, by a new rule limiting debate to senators. Adams grew increasingly distant from both Jefferson and Hamilton, whom he viewed as grasping rivals for power. He had also learned, to his dismay, that Hamilton had secretly discouraged some electors from voting for him in the first presidential election -- a slight that Adams neither forgot nor forgave. Jefferson and Hamilton soon resigned from the cabinet but Hamilton, with a stronger stomach for direct confrontation, stayed long enough to fill the still forming executive branch with his followers.

Though a more moderate revolutionary government in France relaxed the Terror in July 1794, as Washington's second term progressed, international tensions continued to dominate partisan debate in the United States. In Europe, France's armies pushed the offense, especially after the rise in the mid-1790s of a young Corsican general, Napoleon Bonaparte. Britain joined the European alliance against France and, with their far-flung empires drawn into the inferno, the whole world seemed at war. "None can deny that the cause of France has been stained by excesses," Hamilton observed at the time. "Yet many find apologies and extenuations with which they satisfy themselves; they still see in the cause of France the cause of liberty.... Others on the contrary discern no adequate apology for the horrid and disgusting scenes which have been and continue to be acted." Jefferson fit in the former camp; Hamilton placed himself in the latter one. For many Christians, Jefferson's sympathy for Jacobin assaults on organized religion compounded the suspicions raised by his Deist beliefs. Hamilton and the Federalists repeatedly warned that Republican rule might lead to similar attacks on churches in America. The specter of militant Jacobin anticlericalism turned religion into a heated partisan issue in American politics.

Although many Federalists favored Britain and the royalist alliance while most Republicans supported France and its allies, virtually all Americans hoped that their country could remain neutral in the European conflict and continue trading with both sides. That would prove a great challenge. Europe's leading imperial powers, Britain and France, had fought off and on for over a century, but ideological differences and France's military aggression now increased the bitterness of the battle. Both sides demanded support from other nations and retaliated against those that refused aid. Washington tried to maintain American neutrality but, following Jefferson's resignation as Secretary of State in 1793, his administration increasingly came under the control of Hamilton's pro-British High Federalists. Although suspicious of Britain's designs on the United States, Adams abhorred the revolutionary regime in France and did little to right the balance.

After stepping down as Secretary of State, Jefferson continued working privately with Madison and a growing interstate network of Republicans to oppose the High Federalists' pro-Britain, pro-business policies. Although Jefferson claimed to want out of public life, Adams saw his retirement from the cabinet differently. "Jefferson thinks by this step to get a reputation as an humble, modest, meek man, wholly without ambition or vanity. He may even have deceived himself in this belief," Adams noted at the time. "But if the prospect opens, the world will see and he will feel that he is as ambitious as Oliver Cromwell," who usurped royal authority during the English Civil War. When Madison followed Jefferson into early retirement, Adams added, "It seems the mode of becoming great is to retire [from public scrutiny]...upon the same principle that no man is a hero to his wife or valet de chambre." Jefferson and Madison so actively organized and led the Republican reaction to Hamilton's programs that Federalists began calling them the Generalissimo and General of the opposition.

Adding to the tension, British naval vessels began intercepting American ships bound to or from French ports and impressing American sailors for service in the Royal Navy. Washington dispatched Chief Justice John Jay to resolve differences between the United States and Britain. But bargaining from a weak position, Jay's controversial British Treaty did little more than accept British limits on American trade with France in exchange for Britain finally evacuating the last of its pre-Revolutionary War forts on U.S. territory. It even failed to stop the British from intercepting American merchant ships and impressing American sailors. The agreement outraged both Republicans at home and the French government, which retaliated by authorizing the capture of American ships trading with Britain. The fledgling United States had no means to protect its merchant fleet, which was now regular prey to both the British and the French. For the first time, Washington's popularity sagged. Jay reportedly said that he could travel from Boston to Philadelphia solely by the light of his burning effigies.

In 1796, at age sixty-four, Washington announced that he would not accept a third term as President. The posturing for succession quickly evolved into a strange sort of behind-the-scenes competition for office. For the first two elections, no one opposed Washington for the presidency. Now the seat was open. The two emerging partisan factions had not yet evolved into institutionalized parties, and they did not yet have mechanisms for formally nominating presidential candidates. They did, however, have clear leading contenders for that office.

Adams was in from the start. Although he once described the vice presidency as "the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived," he nevertheless saw it as a stepping stone to the presidency. "I am heir apparent, you know, and a succession is soon to take place," he wrote to his wife in January 1796. After eight tedious years as the "Prince of Wales," as he termed the Vice President's position, Adams never would have voluntarily relinquished his claimed right to inherit the throne. Hamilton may have coveted the presidency for himself or preferred a loyal High Federalist for the post over the more moderate Adams, but the Vice President's status made it unlikely that any other Federalist could displace him without fatally dividing the party's electoral vote. Jefferson was the obvious Republican contender. Nobody within his party seriously challenged him.

No candidates openly campaigned for the presidency in 1796 or even publicly declared their interest in holding the job. Washington had acted that way in 1788 and 1792, and his would-be successors were careful to emulate him. Jefferson remained in Monticello; Adams went home to his farm near Boston. Others conspired on their behalf, typically without consulting them.

As it turned out, Adams secured votes from 71 of the 139 electors -- or one more vote than he needed for the requisite majority -- in what was to be the last old-style presidential election. Jefferson was the runner-up with votes from 68 electors, and, as the Constitution then stipulated, he became the Vice President.

Adams swept the northern states, gaining votes from every elector in New England, New York, and New Jersey. Delaware also went for Adams. Jefferson carried the South and West, except for votes for Adams from one elector in Virginia and another in North Carolina. The two nascent parties had secured regional bases of support, where they dominated state and local politics as well. The middle states of Pennsylvania and Maryland split their votes and emerged as key political battlegrounds of the future. For the only time in American history, partisan opponents served together as President and Vice President.

Immediately after his election in 1796, Adams reached out to the Republicans. He suggested that Madison lead a bipartisan mission to negotiate an end to the trade dispute with France and that, as Vice President, Jefferson serve in the cabinet. Although he accepted the vice presidency, Jefferson declined to work with Adams or support the Federalist agenda. The division between Adams and Jefferson, and their respective factions, had grown too wide to bridge by such means. Jefferson would preside over the Senate as the Constitution prescribed, and use that position to rally the Republican opposition. "My letters inform me that Mr. Adams speaks of me with great friendship, and with satisfaction in the prospect of administering the government in concurrence with me," Jefferson wrote to Madison after the election results became known. "If by that he meant [my participating in] the executive cabinet, both duty and inclination will shut that door.... The Constitution will know me only as a member of a legislative body."

Adams ultimately filled his cabinet with holdovers from the Washington administration. Most of them were High Federalists and more devoted to Hamilton than to their new President. This would cause Adams a great deal of consternation in the coming years.

Adams and Jefferson acted respectfully toward each other during their term together, but always at a distance. Partisan differences had become too fierce for their friendship to survive. As they were walking home together after a preinauguration dinner with Washington, Adams raised the issue of his peace mission to France. He informed Jefferson that Federalist legislators had insisted that only their partisans be sent on the mission. The two old friends soon reached an intersection "where our road separated," Jefferson later recalled, "his being down Market Street, mine off along Fifth [Street], and we took leave; and he never after that said one word to me on the subject, or ever consulted me as to any measures of the government." From that point forward, their paths, and those of their parties, diverged ever more sharply.

The threat from France consumed the Adams administration from the outset and mired it in partisanship throughout. By the time Adams took office in March 1797, French naval vessels and privateers had intercepted hundreds of American merchant ships and France had substantially restricted trade by the United States in retaliation for Jay's Treaty. All this impacted mainly the commercial Northeast, a Federalist bastion, fueling anger at France in that region. Yet, many Americans, especially in the agrarian South, where republicanism held sway, were still most leery of Britain and remained positively disposed toward France and its revolution. Within days after he became President, Adams learned that the revolutionary regime in France had refused to receive the new American ambassador named by Washington, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, an aristocratic former Revolutionary War general from South Carolina with sympathies toward France's old royalist government and who also was the brother of Federalist leader Thomas Pinckney.

In a bellicose address to Congress two months later, Adams urged Americans to prepare for war even as he reiterated his determination to send a peace mission to France. Reactions to the President's policy followed party lines, with the Republican press becoming especially vitriolic in condemning an alleged rush to war. When Adams pushed ahead with efforts to resolve differences with France, he was, as he had told Jefferson he would be, blocked by leaders of his own party from including Republicans in the peace delegation. Ultimately, Adams chose to send back Charles Cotesworth Pinckney along with Virginia Federalist John Marshall and Massachusetts politician Elbridge Gerry, a political independent and close friend of the President. In March 1798, however, Americans heard that French officials refused to receive the delegation without the United States making an advance payment, which amounted to tribute or a bribe simply to begin negotiations. Americans felt humiliated by the stipulation, which was not how respectful adversaries were presumed to act at the time. The demand was made by three French officials, whom Adams diplomatically identified simply as agents X, Y, and Z, and the incident became known in America as the XYZ Affair. In response, war fever gripped the nation.

Rumors spread of an imminent invasion by France, possibly using freed Blacks from the French West Indies as troops. The threat seemed realistic to some frightened Americans, though not to Adams and never to leading Republicans. By that time, France's revolutionary armies had overrun much of Europe, dislodging long-established political, economic, and religious institutions as they went. America was next, High Federalists ominously warned.

To counter the already crippling impact of French attacks on American shipping, Adams proposed building a navy and raising war taxes. Addressing the purported risk of a Jacobin invasion, in July 1798, Federalists in Congress also passed legislation tripling the size of the regular army from about 4,000 soldiers, who were stationed mainly on the western frontier to deal with threats from Native Americans, to nearly 15,000 soldiers, with the new troops to be stationed in the eastern states. Adams considered this so-called Additional Army unnecessary and Republicans viewed it as potentially dangerous. Deeply suspicious of High Federalist intentions to create a strong central government, Republicans saw a domestic standing army as a clear and present threat to states' rights and individual liberty. Despite his reservations about it, Adams signed the legislation for the Army along with bills for his Navy and the war taxes. These measures steeled the Republicans against him.

In 1798, after debating a declaration of outright war against France, which was backed by High Federalists but vigorously opposed by Republicans, Congress enacted a lesser measure authorizing U.S. warships to engage French vessels in international waters. The resulting naval battles of 1799 and 1800 between American and French ships became known as the Quasi-War. Hamilton pronounced himself "delighted" with Adams's performance in the mounting crisis while Jefferson privately denounced it as "insane." Fearing the worst from France, Americans initially rallied to the President and his party. For the first time in his career, Adams became genuinely popular -- and he loved it.

The partisan clashes over the American policy toward France intensified in 1798, when High Federalists in Congress turned to matters of internal security in wartime. The High Federalists claimed that the French government might actually whip up support among its American sympathizers, especially among Republicans and recent immigrants from Europe. Indeed, the French armies had relied on resident aliens and local republicans for help in conquering European territory. France's ambassador, Citizen Genêt, once even appealed for public support in the United States to try to overturn Washington's neutrality proclamation. Some Federalists charged that, in an invasion, France might successfully rally internal opposition to the government, though the Republicans in Congress dismissed this as impossible in America and feared that the Federalists sought simply to clamp down on them. The High Federalists took aim at both foreigners within the country and critics of the government in the ever more partisan and vitriolic press. By this time, a number of openly Republican newspapers had gained popularity, most notably the Aurora in Philadelphia, offering some measure of balance against the traditionally pro-Federalist press.

In mid-1798, High Federalists pushed through Congress, and Adams signed, the Naturalization, Alien, and Sedition Acts. These laws raised the bar for citizenship, authorized the deportation of foreigners, and outlawed false and malicious criticism of the government in the press or by individuals, including by opposition politicians. A Federalist judge could readily stretch the interpretation of the Sedition Act to reach virtually any form of negative editorial comment in Republican newspapers, and even many Federalists viewed the measure as a blatant move to suppress the freedom of the press and domestic opposition. These acts "were war measures," Adams later explained, "intended altogether against the advocates of the French and peace with France." Presiding over the Senate when they passed, Jefferson strenuously opposed the acts in both public and private, as extreme encroachments on liberty, as did Republicans generally. At first, however, these measures proved popular with the frightened public and Federalists rode them and America's fears of France to victory in the 1798 congressional midterm elections.

In the last two years of his term, however, Adams's popularity seemingly waned and the Republican opposition gained traction. The naval war with France, which proved exceedingly costly and further disrupted foreign trade, led to a soaring national debt and the collection of ever more taxes, which many Americans resented. Republican attacks on the Adams administration took their toll as the public began to realize that, despite the ongoing naval clashes, France was not going to mount an invasion of America. Before long, the Sedition Act and Additional Army began to seem unnecessary and unwise. Republicans painted them as calculated steps toward imposing an authoritarian regime in the United States, perhaps even to instituting an American monarchy.

Rather than help to defuse partisan differences and unite the country, the proximity of Adams and Jefferson in office as President and Vice President served to personalize every clash and to excite the sense that an epic confrontation between them was imminent in the next presidential contest. The stage was set for the election of 1800: America's first and most transformative presidential campaign.

Copyright © 2007 by Edward J. Larson

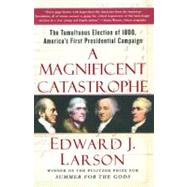

Excerpted from A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America's First Presidential Campaign by Edward J. Larson

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.