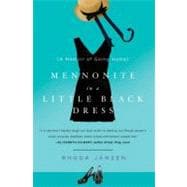

Not long after Rhoda Janzen turned forty, her world turned upside down. It was bad enough that her husband of fifteen years left her for Bob, a guy he met on Gay.com, but that same week a car accident left her injured. Needing a place to rest and pick up the pieces of her life, Rhoda packed her bags, crossed the country, and returned to her quirky Mennonite family's home, where she was welcomed back with open arms and offbeat advice. Rhoda's good natured mother suggested she get over her heartbreak by dating her first cousin he owned a tractor, see.

Written with wry humor and huge personality and tackling faith, love, family, and aging Mennonite in a Little Black Dress is an immensely moving memoir of healing, certain to touch anyone who has ever had to look homeward in order to move ahead.

"It is rare that I literally laugh out loud while I'm reading, but Janzen's voice singular, deadpan, sharp witted and honest slayed me." -Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love

“This book is not just beautiful and intelligent, but also painfully even wincingly funny. It is rare that I literally laugh out loud while I'm reading, but Rhoda Janzen's voice singular, deadpan, sharp witted and honest slayed me, with audible results. I have a list already of about fourteen friends who need to read this book. I will insist that they read it. Because simply put, this is the most delightful memoir I've read in ages.”-Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love

“This is an intelligent, funny, wonderfully written memoir. Janzen has a gift for following her elegant prose with the perfect snarky aside. If it weren't for the weird Mennonite food, I would like very much to be her friend.”-Cynthia Kaplan, author of Why I'm Like This and Leave the Building Quickly