The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

one

SEARCHING FOR GODS AMONG THE HIPPIES

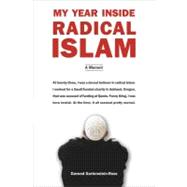

Before I was an FBI informant, an apostate, and a blasphemer, I was a devout believer in radical Islam who worked for a Saudi-funded charity that sent money to al-Queda. At the time, it all seemed pretty normal.

On the inside of a radical Islamic group, there are many rules to remember. A lot of them involve limbs. I could eat using only my right hand. I could never pet a dog or shake hands with a woman. To avoid Allah's wrath, I had to roll up my pant legs above the ankles. On the other hand, shorts on men had to extend below the knee or they were indecent. I believed in all of this and more. I believed that Jews and other nonbelievers had to be conquered and ruled as the inferiors they are.

Funny thing, I was born Jewish. At twenty-three, with my nose in a wool prayer rug, I had to pray for the humiliation of my parents.

This is a story about the seduction of radical Islam, which, like love, can take its devotees suddenly or by degrees, and the long, dangerous climb out. It is a story of converts trapped by extremist views that once seemed alien, furtive calls to the FBI, and a surprising series of revelations that changed my life.

**

My name is Daveed Gartenstein-Ross. If you went looking for my childhood home, you'd snake along I-5 out of California, follow the green-and-white signs to the Elizabethan-themed tourist town of Ashland, Oregon, and wend your way into one of the town's countless subdivisions. There, you would find my house at the end of a lazy cul-de-sac. It wouldn't be hard to spot. My neighbors all had perfect green lawns, while we had the rocks and weeds of an old riverbed. In the back, we kept an untamed jungle of trees and flowers. Our neighbors did not complain; we were on the hippie end of a hippie town.

Like most people who grew up in Ashland, I would complain constantly that there was nothing to do. But I always knew that I would miss the place. Ashland was a liberal oasis in conservative southern Oregon and it brimmed with counterculture. There was an award-winning Shakespearean theater. There was Lithia Park, designed by Golden Gate Park's creator. And there was the telling fact that this hamlet of only fifteen thousand boasted close to a dozen bookstores.

My parents fell in love with Ashland during a brief visit when I was three years old. For those who are drawn to the town, it is the peaks they see first. The Siskiyou Mountains meet the Cascades in Ashland, one stop along the Cascade's northward crawl to Mount St. Helens. It is these hills that give the best view of the town. A short hike would take you to a vantage point above the park where you could see my old childhood haunts: the plaza and the ice cream shop, the baseball diamonds, the dirt lot off C Street where my friends and I used to race our bikes.

My family moved a couple of times before settling down at the end of our cul-de-sac. We lived first in a brown ranch house in the Quiet Village neighborhood before spending a half a dozen years in a town house on sloping Wimer Street. Though we moved a few times, every place we lived in had the same serene New Age feel inside.

My parents' artwork spoke a great deal about their brand of religion. Various scenes from Jesus' life graced the living room. In the backyard stood a small white statue of Buddha. They were sort of Unitary Jews who esteemed Jesus and Buddha equally.

Though my parents were from Jewish backgrounds, they weren't happy with traditional Judaism and decided to join a new religion when I was still a toddler. It was known as the "Infinite Way." My dad once described the group as a "disorganized religion," in contrast to organized religion: it had no membership, no dues, no nonprofit corporation, and no enforcement doctrine. The group was founded by Joel Goldsmith, who was also born Jewish but became a Christian Scientist; he left Christian Science when his ideas diverged from those of Mary Baker Eddy. Joel, whose followers called him by his first name, founded the Infinite Way around 1940, but didn't name it then. Instead, he simply started teaching spiritual principles late that year.

The group's name came seven years later, when Joel published a book calledThe Infinite Way. Joel's teachings focused on awakening people to their unlimited potential that could only be harnessed through spiritual consciousness. As Joel explained: "The necessity for giving up the material sense of existence for the attainment of the spiritual consciousness of life and its activities is the secret of the seers, prophets, and saints of all ages."

In an effort to make the spiritual foremost in their own lives, my parents spent a lot of time meditating. Often I would burst into the living room-excited to share something I had seen or read or some small accomplishment, the way kids so often want to-only to find my parents sitting on the couch silently, their eyes closed, their focus on another world.

My parents' love for spiritual figures and religious traditions didn't end with Jesus, Buddha, and the Old Testament prophets. They also cherished the wisdom of Rumi, St. Augustine, and Ramana Maharashi.

And they drew lessons from Zen, Taoism, and Sufism. Upon hearing of my parents' syncretistic views, a friend once jokingly referred to them as "Jewnitarians."

**

People often present the stories of their religious conversions as though their lives were completely normal, and then there was some great thunderclap. My experience, and the experience of other converts I have known, suggests that it's not that straightforward. Instead, a religious conversion comprises a series of seemingly unrelated events that are later revealed to have had a purpose: they are pointing toward devotion to a god that you never knew. And strange as it may seem, my debates with fundamentalist Christians were milestones on the path to radical Islam.

These debates came when Christian friends tried to push me on my religious views. Mike Hollister is the one I remember best. We met at a debate tournament when I was a high school sophomore. Mike was from the state of Washington. Unlike most high school debaters, he was also an athlete. Six feet tall with light brown hair, Mike played varsity soccer. His athleticism set him apart from the other debaters by giving him an unusually strong presence.

Given the geographic distance between us, there's no easy way to explain why our chance meeting grew into a friendship. We shared a passion for policy debate and a similarly quirky sense of humor-but these alone don't make a friendship. The best explanation is that Mike found me interesting because I was unlike any of his other friends, and I felt the same about him. Mike appreciated my intensely analytical approach to the world, my willingness to debate and discuss every imaginable subject, from politics to economics to baseball. And I was interested in how Mike's worldview differed from that of my other friends. He was traditional and conservative, values alien to my parents' Ashland.

Although we remained friends through college, Mike's descent into fundamentalist Christianity disturbed me. Having been a nominal Christian through high school, he started to become serious about his faith soon after he started classes at Western Washington University, in Bellingham. Christianity became more central to his identity-and I noticed him becoming less fun and less open-minded.

While Mike stayed close to home, I went three thousand miles away for college, to Wake Forest University, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina in the fall of 1994. I was drawn mainly by scholarship money. My parents had more books than dollars, and paying for a private college without a scholarship would have been hard.

With its closely trimmed lawns, tennis courts, and a golf course, Wake Forest's campus looked like a country club. While this may seem welcoming, and surely was to the majority of students who would eventually join country clubs, it made me feel all the more the stranger. I did not make the coast-to-coast drive in my beat-up red 1985 Toyota Tercel that it would have taken to have the car on campus. But if I had, the car would have stuck out among the BMWs, Mercedeses, and new sports sedans that packed the parking lots. From the day I arrived on campus in red Chuck Taylor sneakers and a flannel shirt, I stuck out almost as much as my car would have. For my first couple of years there, I felt isolated, alone.

I decided to visit Mike early in the summer of 1996, driving up to Washington to see him. Since Wake Forest's school year ended earlier than Western Washington's, classes were still in session when I arrived. By then Mike had become deeply involved with a group called Campus Christian Fellowship. I hung out with him and his college friends, who were also fundamentalist Christians, for about a week. They were perfectly nice, but struck me as dangerously naÔve. They seemed to shut themselves off from so much of the richness and ideas that life had to offer.

**

I met Mike's girlfriend over lunch during that visit. Amy Childers stood about five feet nine and had intense blue eyes. Within the first three minutes of meeting her, she asked me: "So why aren't you Christian?"

I was taken aback and offended. What business of hers was it? Though my identity as a Jew was far from central to my life, I immediately shot back, "Because I don't need to be Christian. Remember, I'm one of God's chosen people."

I found the Old Testament notion that the Jews were the "chosen people" rather absurd, but thought that might be an effective parry.

My response caught her off guard. Amy muttered something about how it was true that I was one of God's chosen people, but she envied Jews who became Christian because they were doubly loved by God. "I mean, God loves everybody," she said, "but Jews who convert get to have a special relationship with Him because they're part of God's chosen people, and also get to accept Christ as their savior. They get to be doubly special."

I managed to steer the discussion in a different direction. We didn't talk about Jesus again for the rest of lunch.

**

I don't think Mike realized how much Amy's question offended me. He simply would not drop the subject of Christianity.

Like many people, I had adopted most of my parents' spiritual beliefs when growing up. Or, at least, I had adopted as much of these beliefs as I could understand; true to their liberal vision, my parents were careful not to push their views of God onto me. I believed that truth could be found in most religions-that Jesus had an amazing connection to God, but so did Buddha, so did many other religious figures. I rejected the Christian idea that Jesus had been God: no matter how deep a person's spiritual insight, there's a fundamental difference between the Creator and his creation.

Knowing my analytical approach to the world, Mike thought he spotted a logical problem that could make me rethink these ideas. He wanted to make me consider the case for Christianity.

Mike homed in on my respect for Jesus. At the time, Mike's favorite Christian author was Josh McDowell, an apologist with a gift for making his arguments accessible to college-age readers. Mike shared a passage from one of McDowell's books,Evidence That Demands a Verdict, with me.

In the passage, McDowell discussed at length C.S. Lewis' claim in his classic book,Mere Christianitythat there were three possible things Jesus could have been: a liar, a lunatic, or the Lord. Both McDowell and Lewis concluded that those were the only three alternatives, and there could be no middle ground. This was because Jesus claimed to be the God in the New Testament. If this claim were true, then one should accept him as Lord. But if Jesus' claim was false, and he knew the claim was false, he would be a liar who had nothing to offer his students. On the other hand, if Jesus believed he was God but wasn't, then he would be a madman. The one thing Jesus could not be, according to this logic, was exactly what I thought he was: a good and wise teacher.

While I found the passage compelling, I was sure that I must be overlooking some fatal flaw. But the argument was put to me forcefully enough that it made me uncomfortable because it suggested that there was some incoherence in my ideas about God.

Contrary to Mike's intentions, this discomfort started me down the path to Islam, and ultimately to radical Islam.

**

As I was leaving Bellingham a few days later, Mike walked me to the car, past the sloping lawns that dotted Western Washington's campus. The setting sun gave the sky a pink hue. Some of the college kids tossed a Frisbee around. A few people who had been studying outside were folding up their beach towels and heading back to the dorms.

Mike made one last effort. "Have you thought about devoting your life to Christ?"

We had spent enough of the visit discussing Christianity that the question wasn't unexpected. But I was a bit annoyed by it-and still didn't have a good answer. "I'm not ready to do that," I said. "I'm young, I have a lot of living to do before I could commit myself to any religion."

"But you never know what will happen to you. You're driving home to Oregon now. What happens if you have a car crash and die? Will you go to heaven?"

I smiled and shook my head slightly. This was another of Mike's clumsy attempts at evangelism. I was one of the first people with whom he tried to share his faith, and his lack of experience showed. I found myself wondering why he cared which god I worshipped.

I looked Mike dead in the eyes. "I'll take my chances."

**

When I returned home, I asked my dad about the "liar, lunatic, or Lord" argument. My dad was a short man with a New York accent who liked to discuss big ideas. He had a beard and black hair speckled with patches of white. Although he worked as a physical therapist, he devoted himself to family life. When I was a kid we had endless walks and talks, and constantly created new games to play together.

Although very few topics were off-limits for my dad, I could tell that my question upset him. My dad had certain hot buttons, and apparently I had unwittingly touched one. He wouldn't yell or become belligerent, but there were signs-slight coloration of his face, speaking faster and louder, biting his lip-that tipped me off to his anger. After I told him Mike's argument, my dad blurted out, "As far as I'm concerned, that's just a kind of idolatry."

My parents had a live-and-let-live attitude toward spiritual matters, so I was surprised by my father's strong reaction. But my thoughts quickly turned to the first of the Ten Commandments, which barred idolatry. There was a reason, I knew, that it came first. (When I was writing this book, my dad told me that I had misinterpreted his idolatry point. Rather than referring to idolatry in the standard Jewish way, my dad's thinking was that every person and thing is divine: it's idolatry, in his view, to say that one person is divine but nobody else is. His intended meaning speaks volumes about my parents' beliefs.)

Beside Dad's response, Christianity felt wrong. The Christians I knew lived shuttered lives, conforming to a model of morality and political opinion that missed out on so much of the big picture.

But Mike's efforts at evangelism came at a time when I had some intense spiritual questions. Not only did I feel isolated at Wake Forest, but I also came close to dying twice before I turned twenty-one. After a couple of brushes with death, I was acutely aware of the emptiness in my life.

I came down with pneumonia during my final semester of high school. By the time I was admitted to Ashland Community Hospital, I was within a few days of death. I spent ten days in a hospital bed. Perhaps it was my relatively quick recovery or my young age, but I didn't have the life-changing experience that people sometimes do when they almost die. I somewhat generically resolved to live a fuller life, but beyond that I remained a normal kid.

The spiritual questions came after the second time I faced mortality. That happened in the fall of 1996, shortly after I visited Mike in Bellingham. I felt very sick when I returned to North Carolina for the next semester. I tried to go on living a normal life despite feeling like I was in the grip of a disease. I was able to tough it out for almost a month, but the lesions in my mouth kept coming, and my stomach grew angrier and angrier. I felt my body gradually breaking down. I wore a bulky winter coat and was always shivering event though it was a warm September. Some days it was a real challenge just to walk across campus.

I went to Wake Forest's notorious student health services a few times to see what was wrong. On one visit the nurse dismissively told me that I had a fever and gave me some aspirin (charging me five dollars for a couple of tablets). Finally, near the end of a miserable month, one of the doctors at student health services recognized that my condition was beyond their expertise, and transferred me to North Carolina Baptist Hospital, in downtown Winston-Salem.

At North Carolina Baptist, they diagnosed me with a digestive condition called Crohn's disease. I stayed in the hospital for about two weeks and had to withdraw from school for the semester. I went back to Oregon to recover. I lost more than forty pounds while I was sick, and was a 119-pound skeleton by the time I got home.

When you're deprived of something you love for a long time, you're sometimes treated to a wonderful process of rediscovery. In the fall of 1996, my rediscovery was the joy of food. My mom would cook me five or six meals a day to help me put weight back on. I would first smell the aromas wafting from the kitchen. I relished the olfactory experience as much as the meal itself. And every time I passed one of Ashland's new restaurants, I'd stop to look at the menu, savoring the thought of applewood smoked bacon or five-spice chicken.

It was just one of the parts of my life that I was examining.

**

I was already asking hard questions because of my illness. My grandfather's death added urgency to them. My grandfather had suffered a stroke about a decade earlier. He had led a brilliant life, eventually becoming the dean at the medical school's clinical campus at Stony Brook University in New York. But everything changed with the stroke. By the fall of 1996, he stayed at Hearthstone, a single-story brick nursing home in Medford, Oregon, where my dad worked.

One day we got a phone call. My grandfather was very sick. Shortly after darkness began to cover the valley, another call informed us that he had died. My dad and I drove through ten miles of downpour to get to my grandfather's room. Near the end of his life, Grandpa could no longer stand the debilitating effects of the stroke. Sometimes he'd cry or scream. But when we got to his room and saw him lying there with the warmth fleeing his body, Grandpa finally looked at peace.

My dad patted his forehead and repeated, "My good dad. My good dad."