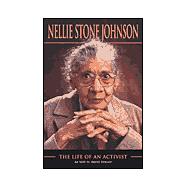

Johnson grew up on a rural Minnesota farm in the early days of the century and went on to rub shoulders with such major historical figures as Hubert Humphrey (who she mentored on civil rights early in his political career), Thurgood Marshall, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Opinionated and outspoken, she is as entertaining as she is informative.