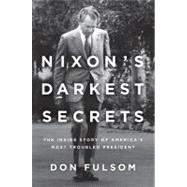

DON FULSOM is a longtime White House reporter and former United Press International Washington bureau chief who has covered presidents Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Reagan, and Clinton. He is an adjunct professor at American University in Washington D.C., where he teaches “Watergate: A Constitutional Crisis.”

“When Richard Nixon boarded Air Force One on August 9, 1974 to return to San Clemente in disgrace over Watergate, I felt an immense sense of joy. After reading Don Fulsom's carefully reported account of Nixon's Darkest Secrets, I'm left with a profound sense of dread that someone so mobbed up, vindictive and downright treasonous could have been elected president of the United States. More than anything, the book makes me wonder how the mainstream media was able to let Nixon skate so long when Watergate itself was really nothing compared to his far more insidious crimes.”—J. Patrick O'Connor, author of The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal and Scapegoat: The Chino Hills Murders and the Framing of Kevin Cooper

"Just when you thought you knew it all, Don Fulsom digs deeper into the mire of the Nixon presidency in NIXON'S DARKEST SECRETS, a book which bristles with revelations about the most disgraced American leader in history. He offers evidence of how Nixon sabotaged peace talks for political gain in 1968, how closely he was connected to the Mafia, his alcoholism and his abuse of his long suffering wife, Pat Nixon."—Muriel Dobbin, author and former White House correspondent

"Don Fulsom, the first reporter to link the Watergate burglars to President Nixon's reelection campaign, has spent more than three decades unlocking the secrets of the the Nixon Administration's roles in a breathtaking array of crimes and cover-ups. His new revelations about President Nixon's ties to powerful mobsters and their stooges in politics, business and labor have been particularly disturbing and are now fully chronicled. Fulson's excellent new book, Nixon's Darkest Secrets, puts an end to the urban legend that President Nixon was run out of office in the wake of nothing more than 'a third-rate burglary.'"—Dan E. Moldea, author of The Hoffa Wars

"All those wonderful times with President Richard M. Nixon come flooding back with Don Fulsom's lovely litany of chiseling, payoffs, 2nd rate burglaries and, yes, public hand-holding with a boozy Bebe Rebozo. If you covered Nixon as I did from beginning to bitter end, no day was complete with a Fulsom question for the uptight press secretary Ronald Ziegler. On every presidential trip, Fulsom was first aboard the White House press plane so he could paste up a smiling picture of Nixon over his seat. And, Nixon did smile on reporters with an endless supply of page one astounders. There are some I missed but fortunately Fulsom recounts the best ones in this book that will delight and inform those once entertained by The Trick."—Patrick J. Sloyan, Pulitzer-prize winning Washington reporter

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.