| Illustrations | p. xi |

| Preface | p. 1 |

| A Bohemian from Bury | p. 7 |

| The River Girl | p. 21 |

| An Alien in America | p. 33 |

| A Clandestine Marriage | p. 64 |

| The Poet's Bride | p. 88 |

| Triple Menage: Bertie, Vivien and Tom | p. 110 |

| A Child in Pain | p. 130 |

| Wartime Waifs | p. 159 |

| Priapus in the Shrubbery | p. 183 |

| Bloomsbury Beginnings | p. 203 |

| Possum's Revenge | p. 235 |

| Breakdown | p. 261 |

| The Waste Land | p. 290 |

| A Wild Heart in a Cage | p. 316 |

| "Fanny Marlow" | p. 340 |

| Deceits and Desires | p. 367 |

| Criterion Battles | p. 390 |

| On with the Dance | p. 410 |

| Mourning and "Madness" | p. 444 |

| Ghosts and Shadows | p. 477 |

| Separation | p. 508 |

| Cat and Mouse | p. 528 |

| Into the Dark | p. 551 |

| Epilogue | p. 582 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 593 |

| Notes | p. 597 |

| Bibliography | p. 673 |

| Index | p. 681 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

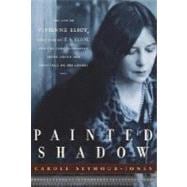

Excerpted from Painted Shadow: The Life of Vivienne Eliot, First Wife of T. S. Eliot, Their Marriage and the Long-Suppressed Truth about Her Influence on His Genius by Carole Seymour-Jones

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.